In Gaza, winter storm makes displacement even deadlier

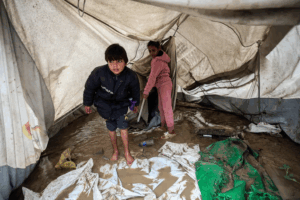

Children inside a tent flooded by rainwater in the Bureij refugee camp, central Gaza, January 2026

Nagham Zbeedat reports in Haaretz on 6 January 2026:

When the rain began to fall on Gaza last week, it did not bring relief. It crept under thin plastic sheets, soaked blankets and turned displacement camps into rivers of mud. By morning, tents had collapsed or drifted away; children were pulled from rising water, and families who had already lost their homes found themselves drowning inside the structure that was supposed to shelter them.

Across Gaza, heavy winter rains flooded makeshift camps where hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have been living for months, many since being forcibly displaced multiple times during the war. With no drainage systems, solid ground or adequate shelter from the elements, rainwater quickly pooled inside tents pitched on sand or rubble and swept away mattresses, clothes and the few belongings families had managed to save from their homes.

In several areas, residents said the flooding reached knee- or waist-level within hours. Some described waking up to water pouring into their tents, forcing them to flee in the dark while trying to carry children, elderly relatives or people with disabilities. Others said they watched helplessly as tents were ripped loose by strong winds and floating debris. More than 40 Palestinians have died in storms from drowning, collapsing buildings or hypothermia this winter, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry.

Children standing inside a tent flooded by rainwater in the Bureij refugee camp in the central Gaza Strip last week. Credit: Eyad Baba/AFP

The flooding has added a new layer of danger to an already dire humanitarian crisis. Aid agencies have repeatedly warned that Gaza’s displacement camps are unfit for winter conditions – lacking waterproof materials, heating, sanitation or proper infrastructure – and the United Nations has warned that Gaza’s humanitarian situation is rapidly deteriorating with the onset of winter storms.

Shukri Bushnaq, 28, from Gaza City’s Zeitoun neighborhood tells Haaretz that most of the tents available to displaced families are not designed to withstand winter conditions. UNRWA recorded that heavy rains and strong winds between December 10 and 23 caused the collapse of least 17 buildings, while more than 42,000 tents sustained “partial or full damage.” “The tents are not for anything,” Bushnaq says. “They can’t help you in the heat of the summer or the cold of the winter. We were humiliated last week.”

As heavy rain fell, residents stayed awake through the nights trying to reinforce their tents and protect what little remained inside; children and women endured chilling temperatures as water leaked through thin fabric and torn plastic.

“You and your family members have to stand on each side of the tent to keep it from flying away in the winds,” he says. “If you look outside, you’ll see the nylon covers on top of the tents flying away and people running after them to get them.”

People trying to save their tent after overnight rainfall flooded their tent camp in Khan Yunis, January 2026

The rain eventually flooded Bushnaq’s tent and caused it to collapse, forcing him, his mother and his three siblings to spend the night outside. “We’re sleeping in the street,” he says. “The rain came back again at night. My fingers turned blue from the cold and the rain.”

The tent, Bushnaq says, had cost around $1,000 – an amount that would once have seemed unimaginable for a structure meant to serve as temporary shelter. Despite the price, it was neither waterproof nor able to withstand strong winds. Replacing it was not an option. Even if his family had the money, he says, tents are scarce, overpriced and often no better than the ones that collapse with the first storm, as nearly all of the tents available in Gaza are made of tarpaulin sheets stretched over iron frames.

Instead, the family tried to salvage what they could. Bushnaq says they were forced to use blankets from shelter schools and charities to block the holes torn open by wind and rain. “The blankets were meant to protect us, but we used them to protect the tent itself,” leaving children and adults exposed to the cold through the night.

As the rain continued, Bushnaq says, the family took turns holding plastic sheets in place and pressing soaked fabric against the tent walls to keep water out, knowing that any further damage could leave them without shelter altogether. “We’re fixing the same tent again and again,” he says, “because there is nothing else.”

There is no standardized or universal system for distributing tents to displaced Palestinians in Gaza. While many of those in need receive tents for free through aid groups, others bypass the intended process. “Some who receive tents through relatives working for these organizations, even if they do not need them,” one resident tells Haaretz. “They sell them to merchants, who then resell them to families in need at a marked-up price.”

Israel classifies many basic winter survival supplies, like tent poles and generators, as “dual-use” – items that Israel claims could be utilized by Hamas. Earlier this week, The Guardian reported that while humanitarian organizations are prohibited from bringing dual-use items into the Strip, Israel has created a parallel system that allows commercial merchants to bring these items into Gaza.

“We are not in the glory days of Islam anymore; we are back to the era of ignorance,” he says, recalling an incident early in the war. “There was an organization that distributed tents, but they tried to make sure they wouldn’t be sold on the market. I watched families wait while the organization installed the tents for them, only to take them down and pack them up to sell after. Out of 20 tents, maybe three or four actually stayed with the families who needed them.”

‘The ground became like a river’

Across southern Gaza, families without tents or with shelters destroyed by rain were forced to depend on one another, turning displacement into a shared, and fragile, survival. Rena Barakah, 25, who lives in Khan Yunis with her parents and younger brother, says she and her family did not have a tent of their own after the heavy rains began last week. Unable to afford a new one after their own tent collapsed, they spent several nights sleeping with neighbors whose tent still remains standing. “We stayed together, many people in one small place,” she says. “There was no privacy, but we had no choice. At least there was something above our heads.”

When her neighbors’ tent flooded, Barakah says, everyone inside rushed to lift blankets, clothes and mattresses out of the water. “The ground became like a river,” she says. “Everything was wet. We were afraid to sleep because the water keeps coming.”

Displaced Palestinians pushing a car through floodwaters following heavy rains in Gaza City in mid-December 2025

Barakah tells Haaretz that the problem was not the rain itself, but the conditions Palestinians are forced to live in. She explains that most tents distributed in Gaza are made from weak materials that cannot survive strong wind or even a few hours of heavy rain. “The rain is normal winter rain. What is not normal is the tent. It is very poor. It breaks fast,” she says. “We don’t know where we will sleep next time it rains.”

Barakah also points to what she described as “deliberate restriction and mismanagement” of aid entering Gaza. “Aid comes in very little amounts, and not for everyone,” she says. “Some people get tents, some get nothing. Some get blankets, but no place to use them.” She says the lack of a functioning drainage system has turned rain into a threat to life. “There is no drainage now,” she adds. “The water has nowhere to go, so it comes inside our tents.”

Despite the seasonal rainfall being a predictable climate pattern, Gaza’s drainage and sewage systems are severely damaged or inoperative, meaning water that would normally be carried away cannot be drained from populated areas.

Before the war, the Gaza Strip had extensive sewer and stormwater networks connected to pumping stations and treatment plants. But Israeli airstrikes and ground operations have destroyed much of that infrastructure, including over 175 km (108 miles) of sewage pipelines, multiple pumping stations and rainwater collection basins, leaving drainage capacity at a fraction of what it once was.

As a result, rainwater and wastewater mix and accumulate in streets and low-lying areas instead of being channeled to the sea. In Gaza City, officials reported that the ability to drain rainwater has dropped to around 20 percent of pre-war capacity.

Municipal authorities have warned that rainwater collection reservoirs, like the large basin in the Sheikh Radwan neighborhood of Gaza City, can no longer discharge accumulated water because the pumps and drainage lines needed to push water toward the Mediterranean have been damaged. This situation increases the risk of overflow into surrounding residential areas during heavy rain.

‘I thank God I don’t have kids’

As families scrambled to repair tents or crowd into whatever shelter remained, others were pulled into moments of sudden emergency, where survival depended on neighbors responding faster than any aid.

Jamal Abu Samra, 30, says he was inside his tent in a refugee camp in Khan Yunis when he heard screaming outside, cutting through the sound of heavy rain and wind. “People were shouting for help,” he says. “Someone said a child is in the water.” Without thinking, he ran out into the rain.

Water had already flooded parts of the camp, he says, turning walkways between tents into deep, fast-moving streams. Together with other residents, Abu Samra helped reach a family whose young son had been swept by the water. “We pulled him out,” he says. “The kid was shaking. He was full of water. We saved him from drowning.

But the rescue, he said, did not bring relief, only anger and exhaustion. “We saved the kid,” Abu Samra says, “but when will anyone save us? When will anyone notice us and our struggle?” He says families in the camp are enduring their third harsh winter in a row, with little change in their living conditions or access to humanitarian aid. “Every winter is the same. Cold, rain, fear. Nothing changes.” Abu Samra says the sense of abandonment weighs heavily. “We don’t have anywhere to go,” he says. “It feels like no one hears our cries or our calls for help. We shout, but there is no answer.”

He says he is grateful he does not have children of his own. “I thank God I don’t have kids,” he admits. “I don’t even know how I would protect them. How I would keep them warm, or safe, or fed in these conditions.” He pauses, then adds, “I see the children here, and my heart breaks.”

Still, Abu Samra says, his worry has not disappeared. His parents decided to return to their home in Gaza City despite the destruction. “At least they have a concrete roof over their heads,” he says. “They went back to the rooms that were not damaged. It’s not a full house, but it has walls.” For him, the distance is another burden. “I can’t reach them easily. I can’t help them,” he says. “I just hope the roof stays standing, and that the rain doesn’t take what little they have left.”

This article is reproduced in its entirety