Warsaw Jews fight and die for freedom

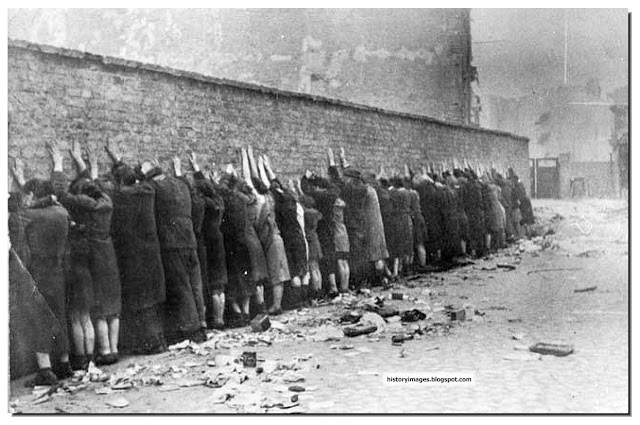

One of the most famous pictures of the Holocaust. German storm troopers force Warsaw ghetto dwellers of all ages to move, hands up, during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, April 1943

“We fought for dignity and freedom, not for territory, not for a national identity”

By David Rosenberg, Rebel Notes

April 18, 2017

Before you go to sleep tonight, take a few moments to reflect on what happened in Warsaw in the early hours of 19 April 1943. That was when troops and tanks of the most powerfully equipped army in the world – the German Nazis – entered the Warsaw Ghetto to burn the ghetto buildings to the ground, massacre the remaining inhabitants, or deport them to death camps. At one time the ghetto, comprising just 1.3 square miles, had held more than 400,000 people – almost all Jews, but also several hundred Roma Gypsies. By April 1943 the inhabitants still numbered 30-40,000 – starved, diseased, beaten – but still holding on to life, just.

In those early hours the Nazi army were shocked to meet armed resistance from a united fighting organisation comprising around 220 people, the oldest of whom was 40. The youngest was a boy called Luciek, a member of the Jewish Socialist Bund’s children’s organisation. He was just 13 years old. They fought with home-made weapons created and smuggled in by Jews living secretly outside the ghetto who were hidden by sympathetic non-Jews, plus a small number of other weapons clandestinely received from the non-Jewish Polish resistance outside. It took the Nazis longer to defeat those resisters than to occupy whole countries.

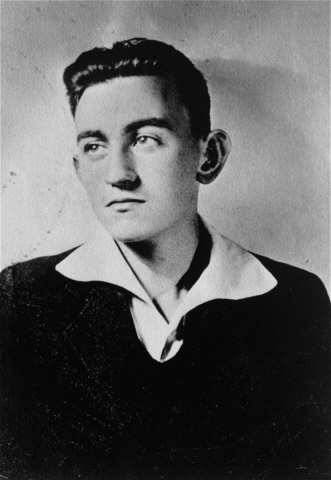

Two of the Jewish fighters in the ghetto uprising.

Those 220 fighters represented an alliance under a joint command of three conflicting political tendencies: Bundists, Communists and left-wing Zionists. The Bundists and Communists disagreed with each other over centralism, authoritarianism, inner-party democracy, cultural politics, and more. They had been bitter rivals for the allegiance of socialist-minded Jewish workers in 1930s Poland. Left-wing Zionists believed that Jews needed a territorial state in Palestine to solve the recurring problems that Jews faced in different countries. Both Bundists and Communists warned that any attempt to impose a Jewish state in Palestine would not only lead to permanent bitter conflict with the population who lived and worked the land there, but also could not solve the problem of antisemitism and fascism in the world. In the ghetto, faced by a deadly enemy, these three disparate tendencies united in action as one.

In the last few weeks a lot of heat, but not much light, has been generated by those who would like to tell the story of Jews, Zionists and Nazis in the ’30s and ’40s in the most simplistic terms of good and evil, and wish away or dismiss any contradictions. The story of the Warsaw Ghetto fighters ought to be told for other reasons, above all to restore names and dignity to those who fought in the most unequal of battles. In telling their history we should embrace the contradictions rather than dismiss them, but also recognise how and why that memory continues to be fought over.

The first moments of the Uprising were described by witnesses during the 1961 trial in Israel of the leading Nazi Adolf Eichmann.

The resistance had organised itself into small units in different locations:

“I was standing in an attic on 31 Nalewcki street when I saw thousands of Germans armed with machine guns surrounding the ghetto. Suddenly they entered… and we, some 20 young men and women (with) a revolver, a grenade, some bombs, happily standing up against the heavily armed enemy. Happy because we knew their end would come. We knew that ultimately they would conquer us. But we knew… they would pay heavily for our lives… When… we threw our hand grenades and bombs and saw German blood pouring over the streets of Warsaw where so much Jewish blood had poured, we rejoiced. The future did not worry us. It was a joy… to behold the wonder of those Germans retreating… they had enough… ammunition, bread and water, which we did not have. Reinforced with tanks they came back on the same day, and we, with our Molotov cocktails set fire to a tank… And when we met in the evening… the number of our dead was small, two men, while hundreds of Germans had fallen either dead or wounded.”

That powerful testimony was given by Tsivye Lubetkin [L], the only woman in the command group, and a left-wing Zionist. Before this trial, Israeli schools had become used to teaching that during the Holocaust, Jews had gone, “like lambs to the slaughter”.

The narrative incorporated these heroic stories of Zionist involvement in the resistance and drew a direct line from resistance fighters in Warsaw to the fighters for a Jewish state.

Inconveniently disrupting that narrative was Marek Edelman, who wrote the most comprehensive memoir of the Ghetto Uprising, in Polish, in 1945. It was translated into Yiddish and English in 1946. Second-in-command during the Uprising, and the last surviving member of the command group until his death in Poland in 2009, he wasn’t even called to give testimony at the Eichmann trial.

Despite his own heroism, Edelman [L] was persona non grata in Israel, a country which leaned on the terrible experiences of the Holocaust to underpin its necessity and legitimacy.

Despite his own heroism, Edelman [L] was persona non grata in Israel, a country which leaned on the terrible experiences of the Holocaust to underpin its necessity and legitimacy.

That was because he insisted on maintaining his pre-war Bundist ideological beliefs: He was a socialist, an anti-Zionist, an internationalist and anti-nationalist until his dying day.

He spoke out in support of justice for the Palestinians. Disgracefully, Edelman’s ghetto memoir remained untranslated into Hebrew until 2001.

Having successfully linked resistance in Warsaw to fighting for Israel, Zionist ideologues drew a sharp distinction between those who fought and those who “passively” and “cowardly” submitted, emphasising brave Zionist fighters, and downplaying or even air-brushing out the Bundists and Communists. Edelman challenged this narrative and could stretch the line of resistance further back in time than the Zionists could. In 1930s Poland the anti-Zionist Bund led the fightback against fascist and antisemitic tendencies in Polish society, whether in the form of Government-backed economic discrimination, street violence or attempted pogroms. In this fight, the Bund could not rely on any support from Zionists except from the small “Left Poale Zion” faction. The communists were too busy engaging in sectarian political wars against the Bund to help. But the left wing of the Polish Socialist Party worked closely with the Bund.

In Poland’s last municipal elections before the war the Bundists swept the Jewish vote. Many historians attribute that to their leadership in the daily fight against antisemitism. It also enabled the Bund to play a pivotal role inside the ghetto resistance, well before an armed battle command was formed.

Poale Zion members and workers marching in a May Day parade with Yiddish signs,Warsaw, 1927. Photo from YIVO archive.

The first underground resistance newspapers that were distributed in the ghetto flew off underground Bundist presses. It was Zalman Frydrych, a Bundist “courier” (the term for those who smuggled themselves in and out of the ghetto on various dangerous missions) who, with assistance from a non-Jewish Polish socialist railway worker, made a gruesome discovery: that deportation trains leaving the ghetto were not transporting Jews in their thousands for “work in the east” but sending them instead to a death camp at Treblinka.

I was fortunate to briefly meet Edelman, whom I regard as a hero, in Warsaw in 1997. But he preferred to be an anti-hero. He did not distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. He spoke of the courage of those Jews who stayed with their families rather than fight; the strong accompanying the weak to a certain death. Edelman said: “These people went quietly and with dignity… Humanity had decided that dying with a gun is more beautiful.” He described the armed rebellion, though, as “the logical sequel to four years of resistance by a population incarcerated in inhuman conditions, a humiliated, degraded population treated as sub-human”, but who had nevertheless established clandestine universities, schools, welfare institutions, orchestras, theatre groups and newspapers. For Edelman it was these acts, resisting to whatever threatened their right to a dignified life, that culminated in rebellion.

A significant number of the arms used by the Warsaw ghetto fighters were manufactured by hand by another Bundist called Mikhal Klepfisz [R] who was being hidden by Polish Catholics in a flat a short distance beyond the ghetto wall. He was 30 years old at the time. That family also hid an 11-year-old called Wlodka, smuggled out of the ghetto – who survived and lives in London today. Wlodka has told me that Klepfisz showed her exactly what he was making and how. He delivered his last consignment after the battle had begun knowing he would not come out.

In sharp contrast with the retrospective Zionist narrative regarding the ghetto fighters, Edelman insisted: “We fought for dignity and freedom, not for territory or a national identity.” He upset the Israeli establishment by declaring that there were no nationalist lessons to be drawn from the Holocaust, only general lessons for humanity, adding that, in his view, the memory of the Holocaust did not belong solely to the Jews but to everybody.

Polish Jewish freedom fighters lined up against a wall by German soldiers in order to be searched for weapons.

One of the most stirring documents smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto was a “Manifesto to the Poles” – directed to the underground non-Jewish Polish resistance. It had the slogan “For our and your freedom” – also the motto of one of the Bund’s underground ghetto newspapers.

There was courageous resistance in many ghettoes. In Vilna (Vilnius), after the ghetto was destroyed, survivors formed a United Partisan Organisation led by an anti-Zionist Communist, Itsik Wittenberg. Both Bundists and left-wing Zionists took part in its operations.

Despite some of the wilder claims aired recently, deeper investigations of the experiences in Poland and in other countries under Nazi occupation reveal that the dividing line between those who fought and those who didn’t cannot be mapped by attitudes to Zionism. A Hungarian survivor, Louis Marton, who was a Zionist in his youth and became an opponent of Zionism in later life, made this point, and also argued that those who went into the ghetto with an idealistic political background, dreaming of a better world, and with a commitment to a politics of change, whether Bundist, Communist or Zionist, were best placed to lead resistance activities.

Tarnow, 1929. Members of the Bundishe boyuvke (the “tough squad” of the Jewish Socialist Bund), acting as marshals in the May Day demonstration.

The recent controversies have focused on the heart of the Nazi beast – Germany – and the actions of some among the (significant) minority of German Jews who were Zionists, but German Jews (largely middle class and more assimilated) were not that representative of Jewish communities in Europe, especially of the larger East European ones which were much more working class and generally more impervious to Zionism, which they saw as a pipe-dream totally divorced from the realistic aspirations of ordinary people..

The Polish Jewish population was more than five times bigger than Germany’s and the fight within Jewish life over attitudes to Zionism and antisemitism was acted out much more sharply there in the 1930s. Bundist leaders in Poland were incandescent about the complacent and defeatist attitude that Polish Zionist leaders had towards antisemitism, and their public statements, echoed gleefully by antisemitic Polish politicians, that there were “100,000 superfluous Jews in Poland” and that “Jews pollute the air of Poland”.

One Bundist leader, Henryk Erlich, described Zionist ideology as “a Siamese twin of antisemitism and every kind of national chauvinism” and characterised the Zionist movement in Poland as the “open ally of our deadly enemy – antisemitism”.

In 1938, Erlich wrote these chilling words: “…if the future of humanity really belongs to fascism… then what truly awaits us… is death and destruction. But death and destruction will be the destiny of all human civilisation and culture. Would Zionism be capable of saving us alone from the fascist deluge. It is ridiculous to even think about it.”

Of course, the relatively small numbers of Jews of Palestine did survive, not because of Zionism though, but because the allies defeated the Nazis at El Alamein. Those polemicists who have been waving around the Ha’avarah Agreement to score a political point against Zionism today, need to ask themselves what would have happened had the Nazis reached Palestine? Would they have tracked down the 60,000 Jews who got there under the Ha’avarah agreement, separated them out and said, “we’ll exterminate the others, not you”? Of course not.

They also need to acknowledge that most German Zionists stayed in Germany and shared the fate of nearly all German Jews there and elsewhere under Nazi occupation, whether Zionist, non-Zionist or anti-Zionist. Reduced to ashes. Cremated equally.

Unfortunately, many people who have justifiably critiqued Livingstone’s half-baked history, and poured scorn on those who unthinkingly defend him, don’t apply the same critical scrutiny to Zionist ideologues and the Israeli political establishment, who have cynically tried to appropriate the history of the Holocaust, and episodes within it, and harness it to their ultra-nationalist and revanchist political outlook today.

The fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto, whether Bundists, Communists or Zionists, who took up arms on April 19th 1943, and were still defiantly fighting against the might of the Nazis in the second week of May, deserve better. Koved zayer ondenk! (Yiddish). Honour their memory!

Below, captured Warsaw Jews marched away for ‘deportation’ May 1943. The uprising had begun on April 19th; it took the Germans 28 days to vanquish the fighters.