Update on the Middle-East upheaval(s)

Uri Avnery, A crazy prophet, 26 Feb

Paul Rogers, The Arab rebellion: perspectives of power, 25 Feb

As’ad AbuKhalil, Rejuvenation of Arab nationalism and/or identity, 25 Feb

Issandr El Amrani, An end to this soft bigotry against the Arab world, 22 Feb

Harry Hagopian, Struggling for the Arab Soul?, 22 Feb

International Crisis Group,Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (I): Egypt Victorious?, 24 Feb

EA World View, From Tunisia/Egypt to Libya/Iran: Notes of Caution on Sudden Change, 24 Feb

Cortni Kerr and Toby C. Jones, A Revolution Paused in Bahrain, 23 Feb

Nicolas Pelham, Jordan’s Balancing Act, 22 Feb

Mary Abdelmassih, Egyptian Armed Forces Demolish Fences Guarding Coptic Monasteries, 23 Feb

Uri Avnery, 26 February 2011

“WHY DON’T the masses stream to the square here, too, and throw Bibi out?” my taxi driver exclaimed when we were passing Rabin Square. The wide expanse was almost empty, with only a few mothers and their children enjoying the mild winter sun.

The masses will not stream to the square, and Binyamin Netanyahu can be thrown out only through the ballot box.

If this does not happen, Israelis can blame nobody but themselves.

If the Israeli Left is unable to bring together a serious political force, which can put Israel on the road to peace and social justice, it has only itself to blame.

We have no bloodthirsty dictator whom we can hold responsible. No crazy tyrant will order his air force to bomb us if we demand his ouster.

Once there was a story making the rounds: Ariel Sharon – then still a general in the army – assembles the officer corps and tells them: “Comrades, tonight we shall carry out a military coup!” All the assembled officers break out in thunderous laughter.

DEMOCRACY IS like air – one feels it only when it is not there. Only a person who is suffocating knows how essential it is.

The taxi driver who spoke so freely about kicking Netanyahu out did not fear that I might be an agent of the secret police, and that in the small hours of the morning there would be a knock on his door. I am writing whatever comes into my head and don’t walk around with bodyguards. And if we did decide to gather in the square, nobody would prevent us from doing so, and the police might even protect us.

(I am speaking, of course, about Israel within its sovereign borders. None of this applies to the occupied Palestinian territories.)

We live in a democracy, breathe democracy, without even being conscious of it. For us It feels natural, we take it for granted. That’s why people often give silly answers to public opinion pollsters, and these draw the dramatic conclusion that the majority of Israeli citizens despise democracy and are ready to give it up. Most of those asked have never lived under a regime in which a woman must fear that her husband will not come home from work because he made a joke about the Supreme Leader, or that her son might disappear because he drew some graffiti on the wall.

The Knesset members who were chosen in democratic elections spend their time in a game of who can draw up the most atrocious racist bill. They resemble children pulling off the wings of flies, without understanding what they are doing.

To all these I have one piece of advice: look at what is happening in Libya.

DURING THE whole week I spent every spare moment glued to Aljazeera.

One word about the station: excellent.

It need not fear comparison with any broadcaster in the world, including the BBC and CNN. Not to mention our own stations, which serve a murky brew concocted from propaganda, information and entertainment.

Much has been said about the part played by the social networks, like Facebook and Twitter, in the revolutions that are now turning the Arab world upside down. But for sheer influence, Aljazeera trumps them all. During the last decade, it has changed the Arab world beyond recognition. In the last few weeks, it has wrought miracles.

To see the events in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and the other countries on Israeli, American or German TV is like kissing through a handkerchief. To see them on Aljazeera is to feel the real thing.

All my adult life I have advocated involved journalism. I have tried to teach generations of journalists not to become reporting robots, but human beings with a conscience who see their mission in promoting the basic human values. Aljazeera is doing just that. And how!

These last weeks, tens of millions of Arabs have depended on this station in order to find out what is happening in their own countries, indeed in their home towns – what is happening on Habib Bourguiba Boulevard in Tunis, in Tahrir Square in Cairo, in the streets of Benghazi and Tripoli.

I know that many Israelis will consider these words heretical, given Aljazeera’s staunch support of the Palestinian cause. It is seen here as the arch-enemy, no less than Osama bin Laden or Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But one simply must view its broadcasts, to have any hope of understanding what is happening in the Arab world, including the occupied Palestinian territories.

When Aljazeera covers a war or a revolution in the Arab world, it covers it. Not for an hour or two, but for 24 hours around the clock. The pictures are engraved in one’s memory, the testimonies stir one’s emotions. The impact on Arab viewers is almost hypnotic.

MUAMMAR QADDAFI was shown on Aljazeera as he really is – an unbalanced megalomaniac who has lost touch with reality. Not in short news clips, but for hours and hours of continuous broadcasts, in which the rambling speech he recently gave was shown again and again, with the addition of dozens of testimonies and opinions from Libyans of all sectors – from the air force officers who defected to Malta to ordinary citizens in bombed Tripoli.

At the beginning of his speech, Qaddafi (whose name is pronounced Qazzafi, whence the slogan “Ya Qazzafi, Ya Qazzabi” – Oh Qazzafi, Oh Liar) reminded me of Nicolae Ceausescu and his famous last speech from the balcony, which was interrupted by the masses. But as the speech went on, Qaddafi reminded me more and more of Adolf Hitler in his last days, when he pored over the map with his remaining generals, maneuvering armies which had already ceased to exist and planning grandiose “operations”, with the Red Army already within a few hundred yards from his bunker.

If Qaddafi were not planning to slaughter his own people, it could have been grotesque or sad. But as it was, it was only monstrous.

While he was talking, the rebels were taking control of towns whose names are still engraved in the memories of Israelis of my generation. In World War II, these places were the arena of the British, German and Italian armies, which captured and lost them turn by turn. We followed the actions anxiously, because a British defeat would have brought the Wehrmacht to our country, with Adolf Eichmann in its wake. Names like Benghazi, Tobruk and Derna still resound in my ear – the more so because my brother fought there as a British commando, before being transferred to the Ethiopian campaign, where he lost his life.

BEFORE QADDAFI lost his mind completely, he voiced an idea that sounded crazy, but which should give us food for thought.

Under the influence of the victory of the non-violent masses in Egypt, and before the earthquake had reached him too, Qaddafi proposed putting the masses of Palestinian refugees on ships and sending them to the shores of Israel.

I would advise Binyamin Netanyahu to take this possibility very seriously. What will happen if masses of Palestinians learn from the experience of their brothers and sisters in half a dozen Arab countries and conclude that the “armed struggle” leads nowhere, and that they should adopt the tactics of non-violent mass action?

What will happen if hundreds of thousands of Palestinians march one day to the Separation Wall and pull it down? What if a quarter of a million Palestinian refugees in Lebanon gather on our Northern border? What if masses of people assemble in Manara Square in Ramallah and Town Hall Square in Nablus and confront the Israeli troops? All this before the cameras of Aljazeera, accompanied by Facebook and Twitter, with the entire world looking on with bated breath?

Until now, the answer was simple: if necessary, we shall use live fire, helicopter gunships and tank cannon. No more nonsense.

But now the Palestinian youth, too, has seen that it is possible to face live fire, that Qaddafi’s fighter planes did not put an end to the uprising, that Pearl Square in Bahrain did not empty when the king’s soldiers opened fire. This lesson will not be forgotten.

Perhaps this will not happen tomorrow or the day after. But it most certainly will happen – unless we make peace while we still can.

.

.

.

.

.

The Arab rebellion: perspectives of power

The Arab popular awakening is provoking serious concern among state and security elites across the west. But Israel’s stance is the most self-defeating of all.

Paul Rogers, 25 Feb

About the author

Paul Rogers is professor in the department of peace studies at Bradford University. He has been writing a weekly column on global security on openDemocracy since 26 September 2001, and writes an international-security monthly briefing for the Oxford Research Group. His books include Why We’re Losing the War on Terror (Polity, 2007), and Losing Control: Global Security in the 21st Century (Pluto Press, 3rd edition, 2010)

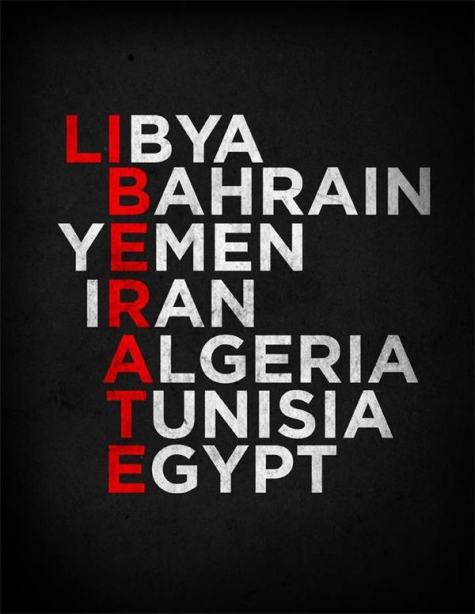

The Arab world is in ferment. The popular upheavals that removed presidents in Tunisia and Egypt, the intensifying protests from Bahrain to Algeria and Morocco, and the revolt in Libya – all testify to the arrival of new generations, voices, and aspirations onto the region’s social and political stage.

These mobilisations, whatever their outcome as a whole and in each case, have already succeeded in placing the demand for change on the agenda of the powerful. But how will power-holders respond?

The Iranian gift

The coincidence that two elite events, long in the planning though they were, took place in the midst of the Arab revolt offers an opportunity to throw light on the question. The International Defence Exhibition and Conference (IDEX 2011) in Abu Dhabi is a major fixture in the global arms-sales calendar; the eleventh Herzliya conference in Israel is a prestigious annual gathering of politicians and security analysts.

Abu Dhabi’s IDEX series started in 1993 and has grown into the region’s largest arms fair, with delegates from fifty countries; the latest event, held on 20-24 February 2011, culminates in a gala dinner earlier for over 2,000 guests. Many of the exhibits aim at enticing wealthy states in the western Gulf that are wary of Iran. Just before the conference started, the Iranians kindly helped things along by sending (with permission from Egypt) two warships through the Suez Canal en route to Syria.

This is the first time Iran had deployed warships through the canal since the Islamic revolution of 1979. The incident provoked Israel to put its navy on a high state of alert as the ships transited north outside Israeli territorial waters.

There is curious connection between IDEX 2011 and the Iranian manoeuvre, in that both ships were constructed in British yards after being commissioned by the Shah who was to be overthrown in 1979. The 1,540-ton light frigate Alvand was built by Vosper Thornycraft and launched in 1968; the 11,000-ton Kharg replenishment auxiliary was built at Swan Hunter’s shipyard at Wallsend and launched in 1977.

A further twist here is that the publicity surrounding the voyage to Syria’s Latakia base can only have improved prospects for arms sales directed against Iran, with anti-aircraft and missile defences much in demand. Equally relevant to the current political moment, however, is that IDEX 2011 displayed a wide range of equipment available for dealing with insurgencies and rebellions, as well as more straightforward public-order control.

Some was on sale from perhaps unexpected sources. In the apartheid era, South Africa forged ahead in the development of a range of light-patrol vehicles designed to help maintain control, especially in urban areas. Now, almost two decades later, South African arms companies are still in there and looking to use their past experience in the townships to help open up new markets. The Paramount Group, for example, is pushing hard its Paramount Low Profile Vehicle (PLPV); it aims both to sell the product – geared primarily for counterinsurgency – and establish local manufacturing centres in the middle east, perhaps in the United Arab Emirates (see “IDEX 2011: Paramount teams with IGG for Middle East drive“, Shephard Group, 21 February 2011).

Much of the focus at IDEX 2011 was concerned with public-order control. France’s state-owned training company Défense Conseil International (DCI) reported – with an exquisite sense of timing, given the killing of protesters in Manama days earlier – that its crowd-control specialists had just started to advise Bahrain’s army on “non-lethal crowd control” (see Pierre Tran, “IDEX: DCI Crowd-Control Specialists Work With Bahraini Army”, Defense News, 22 February 2011).

DCI also announced that it had sent a team of specialists to Libya “aimed at bringing the Libyan air force’s Mirage F1 fighters back into active service”; though there was no indication of how they might then be used.

The view from the summit

IDEX 2011’s five-day programme closely followed the Herzliya conference on 6-9 February 2011, held under the auspices of the Institute for Policy and Strategy (IPS) in Israel. The agenda of this eleventh such gathering was set well in advance of the popular revolts across the Arab middle east, but analysis of the implications of the current tumultuous events – including for Israel – was central to the deliberations.

A striking feature of such events, again evident at Herzliya, is the range of influential actors that are nervous at the prospect of more democratic governance. Four such groups are worthy of note.

First, many western statesmen who voice welcome for the changes, for example, have also long built close links with “stable” autocracies in the Arab world. Their unspoken though sometimes half-revealed concern is that democracy would be messy and discomforting.

Second, elite groups within the region are very worried that the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt will extend to their own states. The leaderships in Jordan, Morocco and Algeria are all trying to find a mix of concessions and reform plausible enough to defuse protest; the House of Saud’s sudden largesse towards its citizens indicates the depth of its own concern, not least as it observes events in Bahrain (see Michael Birnbaum, “16 miles away, Saudi Arabia’s watchful eye looms over Bahrain’s unrest“, Washington Post, 24 February 2011); and Iran’s power-structure is fearful that the domestic opposition will revive in the wake of the Arab protests (see Nasrin Alavi, “Iran’s resilient rebellion“, 18 February 2011)

Third, al-Qaida is discomforted by the fact that the popular insurgencies – something the movement might be expected to welcome – do not find inspiration in its version of Islamist revolution (see “The SWISH Report (18)”, 17 February 2011). The process of change in its early stages, and al-Qaida may yet benefit if new forms of governance fail to deliver in the face of entrenched economic problems; but in the short-term, Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri’s brainchild faces the most difficult circumstance imaginable – irrelevance.

Fourth, there is Israel, whose most immediate fear is that a reformed government in Cairo will respond to public pressure and end the embargo of Gaza. That substantial change would likely require Israel’s army to reoccupy the southern part of Gaza and isolate the Philadelphi corridor, in turn making clear that Israel alone was treating Gaza as an open prison.

But Israel’s concerns go far wider. They were discussed at Herzliya by key international figures who included the Nato secretary-general Anders Fogh Rasmussen, Britain’s defence minister, Liam Fox, and the former head of the US’s national-security council General James Jones.

Democracy vs fixity

Israel’s dominant perspective is that the United States is losing its potency across the region, in great part through its readiness to abandon presumed guarantors of stability such as Hosni Mubarak. More broadly, Washington seems willing to countenance unpredictable political change that (in the Israeli view) carries the risk of “the street carrying the day” and of protesters unrepresentative of the majority being propelled to power.

Israel’s conclusion from these two perceptions – the decline in Washington’s power and regional uncertainty – could be to seek to strengthen its links with influential states (such as China, Russia, India, South Africa, Brazil and even Azerbaijan). There is little if any sign that Israel will upgrade its efforts to seek a just peace with the Palestinians it still has a chance to do so (see Barbara Opall-Rome, “Hedging Against America”, Defense News, 14 February 2011).

A significant exchange at the Herzliya conference highlights the core issue at stake in the relationship of the Arab awakening to the security of states in the region. James Jones both rejected the notion that US influence was in retreat and stressed the need for Israel to seize the opportunity to negotiate: “Failure to act could ignite a repetition of Egypt on streets in neighbouring countries. Will extremists win the hearts and minds of the young Arab street? Or will moderate voices prevail for a two-state solution? This could be the most important national security question for our time, and if we fail, history will not forgive us.”

The response of Amos Gilad, director of political-military affairs at Israel’s defence ministry, was revealing. “Democracy and stability”, he said, “cannot coexist in the Arab middle east”, as free elections would only bring extremists to power.

This view does seem to be shared across most of the Israeli political establishment, including the government of Binyamin Netanyahu and its coalition partners. Many progressive Israelis reject it, but they have little influence in an atmosphere dominated by the right. This powerful consensus suggests little prospect of immediate change, even as the wider region is undergoing a transformation. So for now at least, the arms companies represented at IDEX 2011 – sanctioned by their political masters and partners – will do their best to sell the means to maintain order and control.

Israel has over decades become used to dealing with rigid autocracies in the Arab world. Now it is faced with unsettling change, to which – in a stance shared only by the most recalcitrant Arab dictators – it seems able to respond only by reaffirming the certainties of an earlier age. The United States and its European allies may be perplexed at the pace of events. But Israel, for the first time in very many years, is quite out of its depth.

![]() Rejuvenation of Arab nationalism and/or identity

Rejuvenation of Arab nationalism and/or identity

As’ad AbuKhalil, 25 February 2011

I have argued in public speeches (although I have not published it yet) about “the rejuvenation of Arab nationalism” in the wake of the war on Iraq back in 1991. I still stand by my thesis and now find ample evidence of it. This is an unreported story of the developments in the Arab world: how the events in Tunisia have affected every Arab country in one way or another, and only Arab countries. How the slogans are being changed from maghrib to mashriq without an organizational orchestration. Tunisia is leading the way: it is setting the tone and pace of the uprisings. I am watching live footage of demonstrations in Tunisia today: and the slogans could not be clearer: a voice of Arab nationalist solidarity. There are flags of most Arab countries in the protests in Tunisia today, and as soon as Bin Ali fled, Tunisians were chanting about the “liberation of Palestine.” Egyptian protesters have been more cautious in their collective action because: 1) Egyptian nationalism is strong and have been nurtured for decades by Sadat and Mubarak AND Camp David; 2) Egyptian protesters are keen on not antagonizing the military at this point for many reasons, and the Arab nationalist manifestation would translate into undermining that precious–by US/Israeli standards–treaty. But these are revolutionary time: Alexander Kerensky is barely remembered in the Russian Revolution. Ahmad Shafiq will be a footnote to the story. The Tunisian protesters will also lead the way in how they keep pushing: after they achieve victories, they push even more. Now they want to bring down the cabinet and to create a constitutional convention. Finally: what is Aljazeera if not an Arab nationalist phenomenon? Also, note that Islamist from Tunisia to Morocco and to Egypt are now increasingly speaking about the “Arab ummah”.

An end to this soft bigotry against the Arab world

The west must revise its low expectations as Moroccans and other Arab peoples speak their minds

Issandr El Amrani, 22 February 2011

Despite the pernicious narratives of past decades, and despite dismissive Western attitudes towards the Middle East and North Africa, Arabs are showing that they can practise democracy after all, says Harry Hagopian. This moment in history is not just a revolt, it is a struggle for the Arab soul.

“He is a pharaoh without a mummy!” – Ali Salem, Egyptian playwright, referring to ex-President Hosni Mubarak, 15 February 2011.

——

Tunisia started it on 17 December 2010 and Egypt consolidated it on 25 January 2011. But as the present success of those two uprisings spreads across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region – Yemen, Libya, Bahrain and perhaps elsewhere tomorrow – it is time to take our analysis one notch higher by examining what is occurring today – not yesterday – and then linking those events to another telling moment that unfolded at the UNSC in New York last week.

It is quite true that those uprisings started by and large as popular, spontaneous and almost leaderless protests by ordinary Arab citizens venting their anger and frustration against poverty, unemployment, unfair distribution of wealth and resources as well as repression, discrimination and wholesale violation of basic fundamental freedoms. Those were largely secular uprisings by men and women from different backgrounds and differing convictions and were neither dictated by the austerity of theocracy nor the precincts of ideology.

It is also relevant to ask the reasonable question “why now?” Why have the citizens of this region embarked today upon such an act of manumission after decades of voiceless submission? Is it that those on the streets today are more courageous than the older generations who were inhibited by power and remained quiescent? I am not a sociologist, or worse an inkhorn, but let me suggest my parallel contributory reasons. The first is that revolutions are not necessarily pre-planned events and it only takes a spark to produce a reaction – and the initial spark in this case was Tunisia that triggered the sluices against accumulated problems with a crippling stasis and suddenly led to an explosion. However, even this spark could have been snuffed out by the repressive tools of any state were it not for the global nature of our world today – unlike the one of yesteryears – that facilitates the younger social network generations keeping in touch with each other through their laptops, iPads, mobiles or networks. Add to this phenomenon the coverage that Al-Jazeera satellite channel provided from every single corner of any country where protests were taking place and the answer becomes somewhat more obvious.

However, this unstoppable and spreading momentum today shouts not solely about economics and social justice but rather about the whole being of the Arab soul – its voice and its vision – which has waned painfully, gradually since the early 1980’s. For far too many decades, Arab politics had fallen silent as Arab regimes had no clear and effective approach toward any of the key issues impacting their collective future. In fact, those few policies they did implement usually contradicted popular feeling and did not represent the interests of their peoples. An Arab world that had been vibrant as much by its mistakes as by its successes had flat-lined and the impetus for almost any motion originated from supporters and allies abroad.

In a sense, it is the MENA leaders’ collective apathy, vision-drain (let alone emigrant brain-drain) and self-centredness that seem to have finally caught up with the peoples of much of the region. So taking to the streets with such resolute stamina – peacefully in Tunisia and Egypt, but with aggression in Libya, Yemen and Bahrain – is no longer a mere act of protest. It is an act of self-determination in the making. Where the USA and the EU have only seen moderation and cooperation, the Arab public has witnessed a loss of dignity and an inability to take free decisions. True independence had been traded in for Western military, financial or political security.

We should not be too easily tempted by an armchair analysis of events that considers the whole region as one homogeneous demographic entity. It is not, nor is its geography for that matter. However, while each country has to be looked at separately, one thing most of the citizens of this region share in common is a political culture based on tribal, religious or personal allegiances (as well as an uneasy mixture of all three) rather than on Western-style political parties. In other words, the variables of those societies in the Middle East and North Africa are not identical to those in the so-called West and it is therefore imperative for us to think a bit outside the box when trying to interpret those events, to follow their course or to fathom their significance.

This might also help us appreciate the subtler realities affecting this vast region. Look at Bahrain for example: in some ways, it has been a model. It gives women and minorities a far greater role than its neighbours, has achieved near universal literacy for women as well as men and has introduced some genuine democratic reforms. Of the 40 members of the [admittedly powerless] Lower House of Parliament, 18 belong to an opposition party. But the problem is that Bahrain has an educated “middle class” no longer content to settle for crumbs beneath a paternalistic Arab potentate – more so since this country is inherently unstable as a predominately deprived Shi’i one (roughly 70 per cent) ruled by a Sunni royal family. This is one patent reason why the upheavals in Bahrain are sending a tremor through other autocracies – whether in the Gulf or further afield.

Also striking are some of the similarities between those countries. While we have learnt that the main square in Manama, capital of Bahrain, is called the Pearl Roundabout, it is more interesting to point out that the 1952 Nasserite revolution in Egypt belatedly inspired the 1962 revolution in Yemen, which split Yemen in half for nearly three decades. There is even a celebrated Tahrir (Liberation) Square in the Yemeni capital of Sana’a.

If we agree with Lord Palmerston, the 19th century British prime minister, that “nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests”, then it becomes clearer that one critical bind facing the West today is our high-profile and decades-long friendships and vested interests with mediaeval rulers. Bahrain, for instance, is a critical ally of the USA and is home to the American Fifth Fleet navy. Moreover, Washington entertains close relations with the ruling Khalifa family as it did with those in Tunisia and Egypt and still does with many other rulers today. So how do we choose between interests and friends on the one hand, and our support for democracy and good governance on the other? A Hobson’s choice in many ways. But if I were advising Prime Minister David Cameron today, I would respectfully suggest tilting toward the second option since this strategic choice would still secure our interests and help forge new friendships albeit on a more even keel.

Omnipresent Western fears about Islamist takeovers in those hotspots demonstrate at times the limitations of our own political imagination or of our Arabist knowledge let alone the reality of the regional dominance of those movements. We should be careful to make the correct distinctions between ‘Muslim’, ‘Islamist’, ‘jihadist’ and ‘al-Qa’eda-inspired movements’ and appreciate that they are not monolithic forces but ones that often oppose each other. While it is truly justifiable for us as Europeans to be cautious of some of their exclusivist and discriminatory teachings, we should also agree for instance that the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and the Yemeni Islamist Congregation for Reform (Islah) Party cannot be qualified simply as rabid anti-Western agents.

Equally pertinently, we should also ask ourselves whether our support of autocratic regimes provides real regional stability, wards off such Islamist “takeovers” and as such reinforces our own security interests. Or whether it could well be counterproductive in that it nurtures the very ‘bogey’ we are understandably trying to keep at bay? Should we not align ourselves with the 21st-century aspirations for freedom of Arabs and help the local regimes understand that representation, not ostracism, would be the better tool of good governance and long-term interests? After all, with our support of autocracy to date, we have not eliminated Islamism, have we? Might we not achieve our goals more coherently if we were more open to their participation in public life?

Some of our policy-makers and pundits have also suggested that seizing the moment to promote the Israeli-Palestinian peace process may well be the best way to placate this public outrage. Much as we may agree with the proposal (a truism, indeed) that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains the central hub of issues affecting the region or emanating from it, we also need to be acutely aware that there is an element both of denial and wishful thinking in this approach. Why? Simply put, because Middle Eastern and North African leaders no longer steer the agenda of the conflicts in ‘their’ region – hence my initial point about the Arab soul, its hopes and dreams, which have been extinguished and replaced by an internal inertia and foreign surrogacy. Besides, and Turkish or Iranian ‘helpful efforts’ notwithstanding, there is an erroneous presumption that a peace agreement acceptable to the West and to Arab leaders will be acceptable to the larger Arab public too. In truth, it is more likely that such an agreement will be seen as an unjust imposition and denounced as a betrayal of deeply-held nationalist feelings. No wonder there was such revulsion, albeit lesser analysis, over the leaked ‘Palestine Papers’. They showed at first glance Palestinian and American politicians exploiting the future hopes of the local populace without referring to them.

But with this Arab inactivity and inconsequential behaviour comes the perennial US role. This is best summed up by the position of the US Administration on 18 February 2011 at the UN Security Council. While all 14 members of the Security Council backed an Arab Resolution, endorsed by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and sponsored by 130 countries, declaring that Israeli settlements in Palestinian territories were illegal and a “major obstacle to the achievement of a just, lasting and comprehensive peace”, the USA – whose president had once demanded a total freeze on settlements – single-handedly vetoed down this resolution.

This US veto cast by Susan Rice was explained away by suggesting that the UN is not the appropriate forum to discuss Israeli-Palestinian issues. Would the Israeli Knesset (parliament) be more appropriate? Or else why not Capitol Hill, which Afif Safieh, a former Palestinian ambassador and member of the Fatah Revolutionary Council since 2009, described in his article ‘Awaiting the Eisenhower Moment in The Majall’a on 5 February as “another Israeli-occupied territory”? This latest US veto speaks volumes about the unerring failure of this Administration – not unlike previous ones – to understand that this vote alone will have undone the 2009 oratory fireworks of President Barack Obama in Cairo and Ankara and his oft-stated assertion that he wishes to extend a hand of friendship to Muslims worldwide. From where I stand, it appears well nigh impossible for a US Administration to have the capacity to prioritise the long-term interests of the American people and to evince a Suez moment that breaks the logjam in this intractable irenic process.

Yet, as the Christian lobbying movement Churches for Middle East Peace (CMEP) declared from Washington DC on 2 February, Palestinians deserve self-determination just as Israel deserves recognition by its neighbours and both parties deserve security. Is this not a win-win solution, or is the colonialism that is being challenged by the Arab masses let alone the occupation that is perpetuating it today still inhabiting our Western minds? In fact, is this slow-motion sprint toward emancipation not being obstructed by totalitarian regimes in the region?

However, while the UNSC veto might appear on paper as a defeat for Palestinians, and while a US abstention or an outright veto were both predictable, the Palestinians should still be satisfied by the degree of support they garnered with 130 countries co-sponsoring the resolution and 14 members of the Security Council voting in its favour. In this sense, the result was not only a strong endorsement of the Palestinian position on Israeli settlements – that they are illegal and an obstacle to peace – but it stripped bare the fig-leaf that masks US-Israeli entrenched biases as much as the failure of the Quartet and its peripatetic envoy. But the question now is more internal in character and challenges the Palestinians to seize this opportunity, coordinate their positions and consolidate their response. Or will they prove once more the truth of Abba Eban’s statement after the 1973 Geneva Peace Conference that “the Arabs never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity”?

The Roman lawyer and philosopher Cicero once stated that “ignorance is the cause of evil”. So given the ferment of the Middle East and North Africa region, it is important that we all recognise the epic significance of this drawn-out moment. This is a popular and trans-national struggle for the dispersed Arab soul, for its lost past and also for its uncertain future. But it must also be acknowledged that this is largely a national and secular revolution that might well benefit Islamists within emerging political configurations and parties once – if – they agree to weave their future together.

Today, nobody can paint with certainty a picture of how the Middle East and North Africa region would look in few weeks, months or even years. In fact, few are the prophets who would predict the political landscape next week let alone next year Where would the ‘revolution’ spread next – into Algeria, into the Palestinian territories of Gaza and the West Bank against a vicious occupation on the one hand and feral Palestinian autocracy in Gaza and the West Bank on the other (with Israel already putting in place contingency plans to counter such an uprising) or will Iraq become the next target? Nor can anyone accurately predict whether the Iranian regime that has countered popular uprisings with furious force and tried to neuter the likes of Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi (ironically companions of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and the Iranian Revolution) will also be toppled by this momentum just as its predecessor regime of Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was in 1979 despite maintaining a facade of strength and stability.

What we can be sure of is that the energy those uprisings have channelled in seven short weeks certainly seems to have challenged decades of top-down domination and has drastically altered the topography of a heretofore stagnant region. Ordinary citizens, encouraged by the spellbinding coverage of Al-Jazeera satellite TV, have conquered fear, locked horns with the threat of political castration, shown raw courage and decided to stretch out in order to touch an ‘Arab Spring’ moment. In fact, they are doing all this no matter the perils or obstacles lurking ahead and no matter the forces – whether homebred or imported – that face, obstruct or even maim and kill them.

Again, we in the West find ourselves in a dilemma in terms of our reaction to those extraodinary events. Perhaps we should stand back and respect this moment of change – as we did in East Europe as well as some parts of Latin America or Africa. It is best if we do not muddy the waters further with uninvited intrusiveness and too much unsolicited – and alas inexpert – advice. Courageous Muslim and Christian men and women across the MENA region are struggling against so many odds to salvage their citizenship rights in their countries after having been boxed in for far too long by local autocracies and foreign oligarchies alike. If we are judicious enough in our standpoints, we might find out that we still have a big role to play in this region once the dust settles and the much harder task of state-building starts in earnest.

Despite the pernicious narratives of past decades, and despite myriad insalubrious jokes about the Middle East and North Africa, Arabs are showing that they can practise democracy after all. This is a struggle for the Arab soul. I do not know whether it will be successful nor what we will deal with in later months … but at the very least it should not make us shudder, but rather make us proud.

—–

“Freedom is a great, great adventure, but it is not without risks. There are many unknowns.” – Fathi Ben Haj Yathia, Tunisian author and former political prisoner, over the role of Islam in politics.

———-

© Harry Hagopian is an international lawyer, ecumenist and EU political consultant. He also acts as a Middle East and inter-faith advisor to the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England & Wales and as Middle East consultant to ACEP (Christians in Politics) in Paris, and he is a regular Ekklesia contributor (http://www.ekklesia.co.ukHarryHagopian [1]). Formerly, he was Executive Secretary of the Jerusalem Inter-Church Committee and Executive Director of the Middle East Council of Churches. His own website is www.epektasis.net [2]

Links:

[1] http://www.ekklesia.co.ukHarryHagopian

[2] http://www.epektasis.net

[3] http://del.icio.us/post?url=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194;title=Struggling for the Arab Soul?

[4] http://digg.com/submit?phase=2&url=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194&title=Struggling for the Arab Soul?

[5] http://tailrank.com/share/?link_href=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194&title=Struggling for the Arab Soul?

[6] http://reddit.com/submit?url=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194;title=Struggling for the Arab Soul?

[7] http://www.newsvine.com/_wine/save?u=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194&h=Struggling for the Arab Soul?

[8] http://view.nowpublic.com/?src=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194

[9] http://www.technorati.com/search/http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194

[10] http://www.stumbleupon.com/submit?url=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194&title=Struggling for the Arab Soul?

[11] http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/14194

[12] http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/tags/1328

[13] http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/tags/5254

[14] http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/tags/3146

[15] http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/HarryHagopian

[16] http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/tags/556

[17] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/uk/

[18] http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/about/donate

—

Abdullah Faliq

Head of Research

The Cordoba Foundation

Westgate House, Level 7, Westgate Road, Ealing,

London W5 1YY Tel. 020 8991 3372

E-mail. abdullah@thecordobafoundation.com

Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (I): Egypt Victorious?

Middle East/North Africa Report N°101 24 Feb 2011

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

It is early days, and the true measure of what the Egyptian people have accomplished has yet to fully sink in. Some achievements are as clear as they are stunning. Over a period of less than three weeks, they challenged conventional chestnuts about Arab lethargy; transformed national politics; opened up the political space to new actors; massively reinforced protests throughout the region; and called into question fundamental pillars of the Middle East order. They did this without foreign help and, indeed, with much of the world timidly watching and waffling according to shifting daily predictions of their allies’ fortunes. The challenge now is to translate street activism into inclusive, democratic institutional politics so that a popular protest that culminated in a military coup does not end there.

The backdrop to the uprising has a familiar ring. Egypt suffered from decades of authoritarian rule, a lifeless political environment virtually monopolised by the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP); widespread corruption, cronyism and glaring inequities; and a pattern of abuse at the hands of unaccountable security forces. For years, agitation against the regime spread and, without any credible mechanism to express or channel public discontent, increasingly took the shape of protest movements and labour unrest.

What, ultimately, made the difference? While the fraudulent November 2010 legislative elections persuaded many of the need for extra-institutional action, the January 2011 toppling of Tunisian President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali persuaded them it could succeed. Accumulated resentment against a sclerotic, ageing regime that, far from serving a national purpose, ended up serving only itself reached a tipping point. The increasingly likely prospect of another Mubarak presidency after the September 2011 election (either the incumbent himself or his son, Gamal) removed any faith that this process of decay would soon stop.

The story of what actually transpired between 25 January and 11 February remains to be told. This account is incomplete. Field work was done principally in Cairo, which became the epicentre of the uprising but was not a microcosm of the nation. Regime deliberations and actions took place behind closed doors and remain shrouded in secrecy. The drama is not near its final act. A military council is in control. The new government bears a striking resemblance to the old. Strikes continue. Protesters show persistent ability to mobilise hundreds of thousands.

There already are important lessons, nonetheless, as Egypt moves from the heady days of upheaval to the job of designing a different polity. Post-Mubarak Egypt largely will be shaped by features that characterised the uprising:

-

This was a popular revolt. But its denouement was a military coup, and the duality that marked Hosni Mubarak’s undoing persists to this day. The tug of war between a hierarchical, stability-obsessed institution keen to protect its interests and the spontaneous and largely unorganised popular movement will play out on a number of fronts – among them: who will govern during the interim period and with what competencies; who controls the constitution-writing exercise and how comprehensive will it be; who decides on the rules for the next elections and when they will be held; and how much will the political environment change and open up before then?

-

The military played a central, decisive and ambivalent role. It was worried about instability and not eager to see political developments dictated by protesting crowds. It also was determined to protect its popular credibility and no less substantial business and institutional interests. At some point it concluded the only way to reconcile these competing considerations was to step in. That ambiguity is at play today: the soldiers who rule by decree, without parliamentary oversight or genuine opposition input, are the same who worked closely with the former president; they appear to have no interest in remaining directly in charge, preferring to exit the stage as soon as they can and revert to the background where they can enjoy their privileges without incurring popular resentment when disappointment inevitably sets in; and yet they want to control the pace and scope of change.

-

The opposition’s principal assets could become liabilities as the transition unfolds. It lacked an identifiable leader or representatives and mostly coalesced around the straightforward demand to get rid of Mubarak. During the protests, this meant it could bridge social, religious, ideological and generational divides, bringing together a wide array along the economic spectrum, as well as young activists and the more traditional opposition, notably the Muslim Brotherhood. Its principal inspiration was moral and ethical, not programmatic, a protest against a regime synonymous with rapaciousness and shame. The regime’s traditional tools could not dent the protesters’ momentum: it could not peel off some opposition parties and exploit divisions, since they were not the motors of the movement; concessions short of Mubarak’s removal failed to meet the minimum threshold; and repression only further validated the protesters’ perception of the regime and consolidated international sympathy for them.

As the process moves from the street to the corridors of power, these strengths could become burdensome. Opposition rivalries are likely to re-emerge, as are conflicts of interest between various social groups; the absence of either empowered representatives or an agreed, positive agenda will harm effectiveness; the main form of leverage – street protests – is a diminishing asset. A key question is whether the movement will find ways to institutionalise its presence and pressure.

-

Throughout these events public opinion frequently wavered. Many expressed distaste for the regime but also concern about instability and disorder wrought by the protests. Many reportedly deemed Mubarak’s concessions sufficient and his wish for dignified departure understandable but were alarmed at violence by regime thugs. The most widespread aspiration was for a return to normality and resumption of regular economic life given instability’s huge costs. At times, that translated into hope protests would end; at others, into the wish the regime would cease violent, provocative measures. This ambivalence will impact the coming period. Although many Egyptians will fear normalisation, in the sense of maintaining the principal pillars of Mubarak’s regime, many more are likely to crave a different normalisation: ensuring order, security and jobs. The challenge will be to combine functioning, stable institutions with a genuine process of political and socio-economic transformation.

-

Western commentators split into camps: those who saw Muslim Brotherhood fingerprints all over the uprising and those who saw it as a triumph of a young, Western-educated generation that had discarded Islamist and anti-American outlooks. Both interpretations are off the mark. Modern communication played a role, particularly in the early stages, as did mainly young, energised members of the middle classes. The Brotherhood initially watched uneasily, fearful of the crackdown that would follow involvement in a failed revolt. But it soon shifted, in reaction to pressure from its younger, more cosmopolitan members in Tahrir Square and the protests’ surprising strength. Once it committed to battle, it may well have decided there could be no turning back: Mubarak had to be brought down or retaliation would be merciless. The role of Islamist activists grew as the confrontation became more violent and as one moved away from Cairo; in the Delta in particular, their deep roots and the secular opposition’s relative weakness gave them a leading part.

-

Here too are lessons. The Brotherhood will not push quickly or forcefully; it is far more sober and prudent than that, prefers to invest in the longer-term and almost certainly does not enjoy anywhere near majority support. But its message will resonate widely and be well served by superior organisation, particularly compared to the state of secular parties. As its political involvement deepens, it also will have to contend with tensions the uprising exacerbated: between generations; between traditional hierarchical structures and modern forms of mobilisation; between a more conservative and a more reformist outlook; between Cairo, urban and rural areas.

-

The West neither expected these events nor, at least at the outset, hoped for them. Mubarak had been a loyal ally; the speed with which it celebrated his fall as a triumph of democracy was slightly anomalous if not unseemly. The more important point is that it apparently had little say over events, as illustrated by the rhetorical catch-up in which it engaged. Egyptians were not in the mood for outside advice during the uprising and are unlikely to care for it now. The most important contribution was stern warnings against violence. Now, Western powers can help by providing economic assistance, avoiding attempts to micromanage the transition, select favourites or react too negatively to a more assertive, independent foreign policy. Egypt’s new rulers will be more receptive to public opinion, which is less submissive to Western demands; that is the price to pay for the democratic polity which the U.S. and Europe claim they wish to see.

With these dynamics in mind, several core principles might help steer the transition:

-

If the military is to overcome scepticism of its willingness to truly change the nature of the regime, it will need either to share power with representative civilian forces by creating a new interim, representative authority or ensure decisions are made transparently after broad consultation, perhaps with a transitional advisory council.

-

Some immediate measures could help reassure the civilian political forces: lifting the state of emergency; releasing prisoners detained under its provisions; and respecting basic rights, including freedom of speech, association and assembly, including the rights of independent trade unions.

-

Independent, credible bodies might be set up to investigate charges of corruption and other malfeasance against ex-regime officials. Investigations must be thorough, but non-politicised to avoid score-settling. There will need to be guarantees of fair judicial process. Independent and credible criminal investigations also could be held to probe abuse by all security forces, together with a comprehensive security sector review to promote professionalism.

-

The democratic movement would be well served by continued coordination and consensus around the most important of its positive and strategic political demands. This could be helped by forming an inclusive and diverse body tasked with prioritising these demands and pressing them on the military authorities.

One need only look at what already is happening in Yemen, Bahrain or Libya to appreciate the degree to which success can inspire. But disenchantment can be contagious too. Mubarak’s ouster was a huge step. What follows will be just as fateful. Whether they asked for it or not, all eyes once again will be on the Egyptian people.

Cairo/Brussels, 24 February 2011

From Tunisia/Egypt to Libya/Iran: Notes of Caution on Sudden Change

James Miller in

James Miller in  Africa,

Africa,  EA Global,

EA Global,  EA Iran,

EA Iran,  EA Middle East and Turkey,

EA Middle East and Turkey,  Middle East and Iran, 24February 2011

Middle East and Iran, 24February 2011 The time of uprising could be measured in a few weeks, or days, or even hours.

Before 14 January, most Americans didn’t know Tunis from hummus. But suddenly the Tunisian regime fell, and President Zine Abedine Ben Ali quickly ended 27 years of rule by fleeing to Saudi Arabia.

Two weeks later, US President Barack Obama gave his State of the Union address. He did not mention the word “Egypt”. Three days later, every American was glued to a TV set to witness the final hours of President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year reign.

It happens that fast, and the whole world changes. Groups of dedicated and peaceful protesters join together, use technology to spread their voices, and bring down dictatorships.

Well, Mubarak’s demise is almost two weeks old. We are impatient for the next regime to fall. It could Libya, or Bahrain, or Iran, or maybe Yemen. It should happen any day now, right?

A step back. Many of the assertions above are completely, or partially, inaccurate. The spark for what appeared to be an overnight revolution in Tunisia came almost a month earlier when Mohamed Bouazizi, a street vendor, lit himself on fire after having his merchandise confiscated by a municipal officer. But before this, there were years of economic and social oppression to drive Bouazizi to his self-immolation and to push others to the streets.

In Egypt, websites had been following the political degradation for at least a year. There were serious signs of trouble, long before the main stream media followed the story, with rigged elections, persecution of political dissent, beatings and killing by police, and bombings slowly eating away at Mubarak’s credibility.

But the more critical misconception about these first two revolutions may be that the protesters in Tunisia and Egypt somehow toppled their dictators. While the protesters in both locations may have been the catalysts for change, they were not its agents. In both nations, members of the government and leaders of the military stepped in on behalf of the people on the ground. Dissent from within their establishments forced both Ben Ali and Mubarak into a corner. They would have to make a choice: face a bloody civil war and coups d’état, or step down.

Libya is not Egypt or Tunisia. Muammar Qaddafi has no centralized government, has no institutions, and has few rivals inside his own government or military. This is why were are seeing a very different pattern in Libya. The protesters are physically taking control of the country, not just a single square, and they are sometimes doing so by force. Each man employed by the Libyan state is being forced to pick sides. Many are joining the protests, but there is no other way for this to play out than violent revolution. There is no government, to speak of, to hold a gun to the back of the dictator’s head.

Iran is also not Tunisia or Egypt, but for different reasons. The identity of the post-1979 pro-regime Iranian is closely tied to the idea that the current theocratic government is the culmination of the Islamic Revolution. Following orders, cracking down on dissenters, and maintaining loyalty to the Supreme Leader is almost an obligation. This is in sharp contrast to Egyptian and Tunisian societies, far more permissive despite their repression of political rivals or freedom of expression.

So far, this has been a difficult identity to change. However, over the last 20 months, more and more of the regime’s support has been eroding, and the cracks are beginning to show. Last week’s defection of an Iranian diplomat in Milan was the latest in a series of defections. Members of the establishment are debating how to best handle the opposition movement, as hard-line loyalists to the regime call for the death of reformist leaders and moderate conservatives push back.

But to this point, the ideology of the Islamic Republic has held out. the Revolutionary Guard and the military have remain loyal, and the world has watched as the police and the basij have beaten and arrested the protesters. The strength of Iran’s military establishment is unparalleled in the region, and its leaders have been consolidating power for 30 years. Add to this formula the perceived need to defend against the omnipresent enemy of the West, and it becomes apparent that Iran has the military order of an Egypt, but with greater loyalty. It has the ferocity of the Libyan regime, but with more political savvy.

The protesters are still showing up, still chanting, still marching, but as the old adage goes, words do not break bones. Events will move to the breaking point, when someone holds a gun to someone else’s head, and everyone is forced to react. With Mir Hossein Mousavi under house arrest, Mehdi Karroubi under the constant guard of security forces in his own home, Hashemi Rafsanjani’s power being challenged on the Assembly of Experts, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s term expiring, and the 2009 spirit of dissent reviving, the question is when that point is reached.

The earthquakes of Egypt and Tunisia built up for a long time on softer ground. It has taken, and will take, much longer for the fault lines to break the foundations of Iran’s government. When it happens, the regime is likely to go quickly, and like a high-magnitude earthquake, the results will be felt far and wide.

We’re already feeling the foreshocks, but the whole world is waiting for the big one.

Nicolas Pelham

February 22, 2011

(Nicolas Pelham is a journalist based in Jerusalem.)

| For more on East Bank-West Bank tensions, see Curtis Ryan, “‘We Are All Jordan’…But Who Is We?” Middle East Report Online, July 13, 2010.

For background on economic change, see Pete Moore, “Guilty Bystanders,” Middle East Report 257 (Winter 2010). Order the issue here. |

When anti-monarchical revolution swept the Middle East in the 1950s, Jordan was one of the few populous Arab states to keep its king. King ‘Abdallah II, son of Hussein, the sole Hashemite royal to ride out the republican wave, has all the credentials to perform a similar balancing act. Aged 49, he has been in charge for a dozen years, unlike his father, who was just 17 and only a few months into his reign when the Egyptian potentate abdicated in 1952. And the son has grown accustomed to weathering storms on the borders, whether the Palestinian intifada to the west or the US invasion of Iraq to the east.

Why is it, then, that the Jordanian monarchy seems so alarmed amidst the revolution sweeping the Middle East today? In part, the king knows he is out of touch with the times. By regional standards, he remains young, but he is still twice the age of the youth marching in the streets from Rabat, Morocco to Manama, Bahrain. The population that he rules has begun to tire of his performance: For over a decade, he has mouthed the platitudes of reform but failed to deliver. And unlike in the 1950s, when Western powers backed his fellow rulers, he may feel than he can no longer fully rely on the support of his main external patron, the United States, which seems to have nudged Husni Mubarak of Egypt toward the exit.

Promises, Promises

So far, ‘Abdallah’s response to the regional uproar has been to retreat inward. On the heels of demonstrations in Amman and other cities, he dismissed the cabinet and promised a new clutch of ministers more responsive to popular demands. But while presenting a reformist face, he moved to reappoint a hardliner, Ma‘rouf al-Bakhit, the prime minister to whom he turned when the kingdom faced its worst-ever terror attacks, on high-end Amman hotels in November 2005. A retired general, ex-head of a top security agency and former ambassador to Israel, Bakhit could be relied upon to crack down on radical Islamists and fiddle with legislative elections to prevent the less militant Muslim Brothers from repeating the electoral successes of sister organizations in Egypt and Palestine. Importantly to a king who reputedly has a penchant for gambling, Bakhit also signed off on Jordan’s first casino. “A puppet,” spat a retired army colonel when asked about the new prime minister.

Bakhit’s first steps in office suggest a counter-reformation more than a liberalization. Within days of his appointment on February 1, the authorities hacked into dissident blogs and closed down websites, sent hired thugs to disperse peaceful opposition protests and placed Layth Shubaylat, a veteran Islamist critic, under permanent police guard. The official news agency, Petra, released diatribes against journalists who questioned royal integrity. Diplomats consider the new cabinet more reactionary than the last.

Initially, though, the appointment of Bakhit seems to have worked in restoring calm. The street protests, never all that impressive, have subsequently failed to acquire Bahraini — let alone Egyptian — proportions. The police responded to the demonstrators with handouts of water bottles rather than truncheons. East Bankers, the term for Jordanians of non-Palestinian descent, have cheered Bakhit’s return. The kingdom’s Palestinian population, perhaps the majority though figures are proscribed, did not rebel. And the Muslim Brothers, too, the country’s largest organized opposition movement, appear at least partly mollified by the king’s decision to grant them an audience, the first such meeting since he ascended the throne in 1999.

But in back rooms, the backbiting is louder than ever. The protests that erupted across the kingdom marked less an uprising than the collapse of a legally sanctioned taboo that rendered the king inviolable and untouchable. Recent weeks have seen an outpouring of criticism — fair and foul — as resentments pent up for a decade found release. The first protests broke out in southern Jordan, focusing on rising prices, corruption and stagnant wages in the public sector, and blaming the country’s ruling class. Unrest rapidly spread to other locales and across social boundaries, including among men who once served in the army. “Soldiers are like other citizens,” says Gen. ‘Ali Habashna, a member of the National Committee of Military Veterans, which claims to represent 140,000 pensioned security men and counts several ex-generals among its ranks. The Committee has called on former law enforcers to break the law by demonstrating without a license. “They’re also hurt by the government. Tunisia and Egypt have opened their eyes.”

Uppity East Bankers

The most vocal protests came from Jordan’s East Bank tribesmen, a pillar of Jordan’s security regime since the Hashemites first rode into the kingdom in 1917. In return for their support, East Bankers have looked to the monarch to provide job opportunities and other patronage. But, under King ‘Abdallah, cracks have emerged in the pact. Privatization has eroded the public sector, long the employer of first and last resort for East Bankers, while the private sector has reaped growing profits. The fact that many of the beneficiaries were Palestinians — after the Black September revolt of 1970, many had their avenues to the public sector blocked — only heightened East Bankers’ ire. In what has become a turbid current in Jordanian politics, the East Bankers perceive a fall from grace as a more sophisticated, globalized nouveau riche, made up particularly of Palestinians, rises. Symbolizing the change, tribesmen rant that that no sooner had they brought their tributary trays of mansaf, the lamb rack doused in yogurt that is prized as Jordan’s national dish, than the king began eyeing his Rolex, in marked contrast to the respectful manners of his father.

Not surprisingly, much of the vitriol is focused on the king’s wife, Queen Rania, who is denounced as an outsider, because of her Palestinian origins, and supposed to be a ringleader of the East Bank’s dispossession. In one petition reflecting the hostile new discourse, three dozen tribesmen lambasted Rania’s lavish lifestyle, portraying her as Jordan’s counterpart to the wife of deposed Tunisian leader Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, through whose relatives much of the country’s business was channeled. The petition accused her of expropriating state land to build her own school, diverting monies from the kingdom’s overstretched budget to finance birthday parties in the Wadi Rum desert, and using her influence to appoint favorites to senior positions or win citizenship for Palestinians, particularly those married to Jordanians. (One bureaucrat who began on a government salary parachuted in to run the king’s diwan, leaving office as a crony capitalist with a luxury house he sold for millions. Similar tales abound: a health minister who contracted work to his own pharmaceutical company, a manpower minister who employed his own migrant worker agency and an irrigation minister who watered his own date plantation.) “Sooner or later,” warned the petition, Jordan would be deluged by “the flood of Tunisia and Egypt due to the suppression of freedoms and looting of public funds.”

The dam at Dhiban, the town 43 miles south of Amman where the protests first flared up, offers a vivid illustration of the upturned hierarchies. Not only did the dam’s construction inundate fertile tribal lands, residents gripe, but it channels water away from the surrounding fields to Amman for the swimming pools of the rich. Local cultivators (with the exception of a former minister) are banned from using the dammed water for irrigation, leaving nearby pastures parched. Farmers who once grew tomatoes have been forced to sell. The inhabitants of Dhiban seethe at the collapse in land prices: While they move to the cities, their town has attracted an influx of “settlers” — Palestinians from the cities buying plots for country homes on the cheap. Privatization of the nearby phosphates factory has further led to the substitution of foreign for local labor, deepening Dhiban’s economic crisis and these East Bankers’ fear of slipping from their once paramount status. Even the gatekeeper of the dam is Palestinian. “We’re a minority in our own country,” says Muhammad Sunayd, a government official who led the first revolt.

The king’s first remedy was to buy off the protesters. As part of an emergency $550 million economic package, he raised government salaries and pensions, and partially reinstated subsidies on fuel and food. But the pay hikes — a meager $30 per month — did little to offset the increases in taxation that the state has also imposed. And the royal attempts to address the complexities of a modern economy with tidbits of noblesse oblige sparked more political demands, for instance, calls for greater representation commensurate to the rising tax and utility bills. “We’re not after candies,” said a leftist opposition leader.

Having failed to dim the outcry, ‘Abdallah resorted to the Hashemites’ time-honored safety valve of dismissing the prime minister. (Jordan’s four kings have changed premiers 72 times.) The move went some distance toward mitigating East Bank anger. Bakhit’s predecessor, Samir al-Rifa‘i, had all the traits East Bank populists despise. He was of Palestinian origin (though he and his father were born in Jordan); he inherited his title (his father was also a prime minister); he ran a private business (Jordan Dubai Capital); and his fiscal austerity measures earned plaudits from the International Monetary Fund, whose recommendations are viewed in Jordan as having instigated the decline of the public sector.

But the tactic has only partly worked. Rather than dull the edge of East Bankers’ demands, the measures have galvanized the protesters to up the ante. A new spate of demonstrations in Dhiban called for more than government jobs, expanding its slogans to include the restoration of lands, or wajihat, that tribesmen claim were assigned to them under the British Mandate. Despite their general approval of Bakhit’s appointment, protesters briefly cut off the country’s two main highways linking Amman to the south.

West Bankers, Too

Ironically, the offspring of the Palestinian fighters who led the 1970 revolt against King Hussein now find themselves among the king’s most ardent defenders. Having reinvented themselves as businessmen, they led a real estate boom in Amman, turning the Jordanian capital into the most populous Palestinian city in the world. In their luxury homes, businessmen drown their sorrows over the billion dollars that brokers say Jordan’s stock exchange has shed during the turmoil in North Africa, and warn of the threat of mobs breaking out of the impoverished suburbs if the protests escalate. “How stupid these people are,” wrote Mahir Abu Tayr in the official daily al-Dustour. “Can’t they see that destroying Jordan would destroy their homes and livelihoods as well?”

The absence of Palestinians in the initial protests was a common East Banker refrain. Palestinians, complained East Bank activists, care more about foreign issues, such as Israel’s wars in Lebanon and Gaza, than local ones.

The truth was rather different. If Palestinians were quiet, it was largely because their leaders were too traumatized by the 1970 crackdown to intervene in domestic politics. Even when they raised their voices at football matches — supporting Wihdat, the eponymous team of the Palestinian refugee camp in central Amman — they risked being clobbered by East Banker forces. The darak, the gendarmerie created by King ‘Abdallah shortly after he ascended the throne, wounded scores when Wihdat fans celebrated their victory over Faysali, a mainly East Banker side, in October 2010. If Palestinians have championed foreign issues, it is largely because they are safer.

Even so, Palestinians tentatively joined the January protests as they spread north. The Society of Muslim Brothers, which for many Palestinians has served as their political voice, lent the demonstrations support, broadening their thrust in tandem to demand that the king relinquish some of his absolute powers and entrust the people — not himself — with choosing the prime minister. In addition, they demanded proportional representation in place of the current election system of constituencies, which is grossly gerrymandered in favor of the predominantly East Banker south. (A parliamentary constituency in Tafila, a southern town, encompasses a few hundred voters, while one in Amman is home to tens of thousands.) Some also demanded citizenship and voting rights for the estimated million-plus Palestinians resident in Jordan who lack both.

The collapse of the Israeli-Palestinian political process and widespread despair of Palestinian statehood any time soon have increased Palestinian demands for realization of equal rights inside Jordan. The latter feeling has been deepened by Al Jazeera’s release of Palestinian negotiators’ records. “Jordan has lost its defensive buffer of a Palestinian state,” says ‘Urayb Rantawi, director of the Amman-based al-Quds Center for Strategic Studies and a sometime royal adviser. “People are no longer waiting. They want their rights now.”

As with the tribes, ‘Abdallah’s seeming disdain for the Muslim Brothers, particularly compared to his father, has fueled the antagonism. Soon after assuming power, ‘Abdallah exiled the representatives of Hamas from his kingdom, and banned membership in that organization, a particular affront to the Brothers’ Palestinian rank and file. He banned the Brothers’ preachers from the mosque pulpits, and padlocked mosque doors between prayer times to thwart subversive public assembly. Bakhit’s reappointment revived memories of his first term, when anti-Islamist measures and vote rigging peaked following the Amman bombings. As a measure of their disenchantment, the Brothers’ political wing, the Islamic Action Front, boycotted the November 2010 elections. As in Egypt, their absence weakened parliamentary credibility and the legitimacy of the establishment’s governing structures.

By the time the protests reached Amman, Islamists, unions, teachers, leftists and white-collar groups had joined in alongside army veterans and tribal chiefs. Middle-class youth who had shrunk from activism sloughed off their fear of Jordan’s efficient, omnipresent mukhabarat — at least on Twitter. Journalists who had previously not only switched off their phones but removed the batteries and SIM cards before whispering court gossip now voiced criticisms with their names publicly attached. “People power in Egypt and Tunis opened our mouths,” said a pharmacist in Wihdat. Beneath a royal portrait, a leading Brother predicted a collision, and the spread of a Tunisian “virus” to the Arab heartlands. “Tunisia’s revolution is like the French. It will hit the Arab world and topple rulers in the same way the French Revolution did in Europe,” said Zaki Bani Rashad, politburo chief of the Islamic Action Front.

Certainly, a bird’s-eye view of Jordan’s demonstrations would have noted certain similarities with Tunisia’s. Both protests began in the south and focused initially on economic issues, acquiring greater political import as they progressed to the north. What the protests lacked in quantity, remarked one participant, they gained in their qualitative spread.

Worryingly for the king, the demonstrators’ demands were echoed in the salons of some of his closest advisers and the complaints became increasingly personal. Despite the likenesses of the ruling couple hanging in their headquarters, leading Muslim Brothers echoed tribal criticism of Queen Rania, sniping that she preferred to spend Ramadan sunbathing on a yacht off the Italian Riviera than in a mosque. The jibes have yet to reach the level of loathing that overthrew North Africa’s leaders, but the royal image has been badly tarnished. In the south, Bedouins hung portraits not of the king, but of Saddam Hussein, the late Iraqi dictator who once showered them with handouts. And the banners celebrating the king’s January birthday, which normally bedeck the kingdom’s towns, were few and far between in 2011. Loaded with ambiguity, the crowds protesting outside Amman’s Egyptian embassy chanted, “Down with Mubarak,” but also with oppression and tyranny region-wide. And more are holding the king directly responsible for the discontent, not only his ministers. “We are asking questions we never uttered before,” said Jihad Barghouti, a veteran leftist leader.

Cards Left to Play

How will the king handle the widening gap between ruler and ruled? Some senior officials predict a Gorbachev moment wherein the monarch opens up the system to preempt the street in setting the pace. But even the king’s own proxies wonder about his ability to change course, noting the past instances of paying lip service to reformist agendas while repeatedly opting to rule by decree. “Political change in the Arab world is linked to regime change,” said Rantawi, who the king appointed in 2002 to draw up a reform program, only to find his recommendations shelved.

Much of the outcome depends on the opposition groups’ success in maintaining a semblance of a united front, and King ‘Abdallah’s in splitting them. The parlous state of the kingdom’s economy, amidst rising fuel prices and mounting public debt, has done much to give Jordan’s rival halves something akin to a common cause for fairer distribution of power and wealth. Tribal leaders in the south spoke of coordinating protests with refugee camp representatives. In the decade since ‘Abdallah took over, Jordan’s per capita GDP has grown from $1,650 to almost $4,000. But the gap between haves and have-nots has widened, and while the rich speak of tightening belts, hundreds of thousands of others have fallen below the poverty line. With a two-pound packet of meat costing 9 dinars (over $12), even those with jobs speak of a struggle of survival. “We haven’t had meat for two months,” said a once middle-class father of four.

While restored subsidies offer temporary respite, businessmen and economists fear that Bakhit will further ease subsidy cuts, thus reversing the fiscal discipline and budget pruning of the Rifa‘i government, deepening deficits which had hitherto doubled and exacerbating Jordan’s long-term economic malaise. “This government can be expected to shift its priorities from sound fiscal management to sound security and stability,” said one of the king’s proxies, noting that in his previous term Bakhit had upped government salaries to buy off dissent. Compounding these concerns, much of the Gulf investment Jordan had attracted prior to the global recession has been repatriated. Cranes hang idle over unfinished tower blocks, including the landmark redevelopment of downtown Amman’s ‘Abdali neighborhood.

The king has many cards left to play. Unlike Tunisia and Egypt, whose populations are mostly drawn from a single “ethnic” stock, Jordan’s polychrome composition makes the citizenry susceptible to policies of divide and rule. Many Jordanians still hold to the nursery-rhyme diktat of keeping hold of nurse for fear of finding something worse; without the royal linchpin, warn many of the king’s men, the country could descend into civil war. Moreover, fear of the not-so-secret police continues to induce compliance. The government’s refugee affairs department running the Wihdat camp bars any resident from talking to a foreigner without permission. Jordanians seeking employment in banks or even as taxi drivers are required to produce a clean bill of health from the mukhabarat. Taxi drivers protest their loyalty to the king almost before citing their fare. But there is a recognition that they do so “not out of love, but out of fear,” says a veteran Palestinian activist.

Should the discontent grow, regardless, where might King ‘Abdallah look next? However awkwardly, the king has already initiated a tentative overture to the Islamists. Much as his father relied upon them as a strategic reserve against a Nasserist-inspired Egyptian tide, he could yet engage them fully. By empowering their disenfranchised followers, particularly Palestinians, such a gambit might help still discontent, as well as attract capital back from the Gulf. But the price would be to weaken further East Banker influence on the governing structures and to lend credence to those who claim Jordan is evolving into a Palestinian state. This move might also impair the king’s strategic orientation toward Israel and, more broadly, his Western patrons, at a time of greater royal need. For all the damage done to the West’s credibility in the region, that is a shift the Westernized ‘Abdallah is unlikely to undertake unless desperation sets in.

A Revolution Paused in Bahrain

Cortni Kerr and Toby C. Jones

February 23, 2011