The victim identity Israel built over generations now fuels its denial of genocide in Gaza

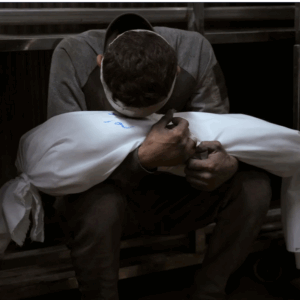

Hossam Azzam holds the body of his child, Amir, who was killed in an Israeli military airstrike, at Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, July 2025

Daniel Blatman writes in Haaretz on 31 July 2025:

For over a century, Turkey has pursued a policy of denying the Armenian genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire between 1915 and 1918. Its mechanism of denial is evident in many areas, including diplomacy, academic publishing, international public opinion and a co-opted scholarly community.

Its objective is to prevent the use of the term “genocide” when referring to Turkey’s actions and to advance an alternative narrative – one that portrays the deportation and mass killing of Armenians as necessary measures taken in response to an internal security threat, rather than as the outcome of a deliberate policy of extermination.

Denial forms a core part of modern Turkey’s national identity. Successive governments in Ankara have framed the mass killings as a legitimate response to an armed uprising, asserting that the events constituted a civil war in which both Armenians and Turks lost their lives, rather than a genocide.

Obscuring the facts and casting doubt on the number of victims is a common strategy in the politics of denial. Among scholars, there’s a broad consensus that approximately 1.2 million Armenians were killed or died. The Turkish narrative, however, asserts that the numbers were significantly lower, roughly 350,000, and that many perished from disease, clashes with local tribes or the hardships of the journey, rather than from explicit orders of extermination.

Casting doubt on the credibility of Armenian and Western sources, such as by means of reports from American consular officials, missionaries and clergy, serves to obscure the political responsibility of the Ottoman leadership, which set out to destroy an entire ethnic group.

Holocaust denial, too, developed its own patterns after World War II, although it remains a phenomenon distinct from the denial of the Armenian genocide. In 1980, Robert Faurisson, a professor of literature at the University of Lyon, published a book entitled “Memorandum in Defense against those accusing me of falsifying history.” In it, he claimed that mass extermination by gas could not have occurred at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp.

Relying on supposedly scientific calculations, Faurisson argued that survivor testimonies and historical documentation were fabricated. He asserted that the size and capacity of the gas chambers could not have allowed for the killing of so many victims at once. He also claimed that the release of Zyklon B gas took too long to kill people, making it impossible for victims to have died within minutes, as many witnesses had testified. Furthermore, Faurisson contended that the removal and cremation of hundreds of corpses in such a short time would have required resources that were simply unavailable to the Nazis.

Faurisson’s claims have been thoroughly debunked by historians, engineers, chemists and other experts. He stands as a clear example of how genocide can be stripped of its historical context through manipulative and pseudo-scientific calculations. As is well known, camp victims were packed tightly into the gas chambers. The ventilation and cremation systems were specifically engineered for the chambers’ intended function, enabling frequent use and the swift removal of bodies.

Faurisson consistently disregarded German documentation, aerial photographs, architectural plans of the crematoria, testimonies from camp guards and, by contrast, numerous survivor accounts and archaeological findings. His pseudo-scientific computations became a textbook example of a denialist tactic: presenting vague, so-called scientific claims while posing questions that deliberately ignore the historical context of the event.

A similarly dangerous trend is unfolding in Israel regarding the horrific crimes in the Gaza Strip. In June 2024, Dr. Lee Mordechai, a historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, published a report titled “Bearing Witness to the Israel-Gaza War,” which has since been updated several times in response to ongoing developments, most recently in July 2025.

The document offers a methodical and detailed account of Israeli actions in Gaza, including actions that may constitute war crimes and potentially even that of genocide. It’s based on eyewitness testimonies, satellite imagery, video documentation, reports from international organizations and numerous accounts from both Israeli soldiers and civilians on the ground. It describes the killing of unarmed Palestinians, repeated attacks on refugee camps, targeting of people seeking medical aid, the deliberate starvation of the population and the destruction of infrastructure, including hospitals, water facilities, power stations, universities and mosques. The report further documents tens of thousands of deaths, most of them women and children, as well as mass hunger.

Alongside this documentation, Mordechai offers an analysis of dozens of public statements by Israeli politicians, rabbis and other public figures calling for the collective destruction of Gaza since the beginning of the war – as evidence of genocidal intent.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories, Francesca Albanese, has also stated regarding the war that explicit calls for destruction and indiscriminate aggression toward Gazans are being heard in Israel, creating an environment that fosters genocide. A similar picture emerges in reports by Amnesty International, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk and other global organizations. Many have warned that the high number of deaths among Palestinian children, women and the elderly reflect Israel’s systemic failure to uphold the principles of proportionality and distinction cornerstones of international humanitarian law.

In an opinion piece published earlier this month in Haaretz, Prof. Michael Spagat, a world-renowned expert in calculating casualties in conflict zones, estimated that the death toll in Gaza has surpassed 100,000. Israel has reduced Gaza to rubble – a place unfits for human habitation. It has indiscriminately killed innocent women and children, targeted doctors and medical and humanitarian aid workers, and created conditions of starvation and deprivation.

This is genocide.

The most prominent rebuttal to these accusations to date came last month. A group of local researchers, including Prof. Dan Orbach, Dr. Yonatan Buxman, Dr. Yagil Hankin and attorney Jonathan Braverman from the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University, published a report of more than 250 pages titled “Debunking the Genocide Allegations: A Reexamination of the Israel-Hamas War (2023-2025).”

The authors of this report use quantitative-statistical research methods and draw on documentation by Israeli sources, both military and governmental, while comparing the conflict to other military engagements, primarily in the Middle East. Challenging the core data on which international bodies base their accusations that Israel is committing genocide in the Gaza Strip, they argue that said organizations rely on figures distorted by Hamas, as well as on unverified or exaggerated reports.

Demographer Sergio DellaPergola, professor emeritus at the Hebrew University, has also participated in this denial approach, apparently driven by a basic desire to reject the claim that genocide is occurring in Gaza, through manipulative calculations. In an opinion piece published earlier this month in Haaretz, DellaPergola criticized international discourse on the war, arguing that estimates placing the number of Palestinian deaths in Gaza at over 100,000 are exaggerated and biased. He claims that these estimated rely on distorted data from Palestinian and international sources, all of which he deems unreliable.

Spagat aptly summed up DellaPergola’s arguments by noting that dismissing data from the Hamas-run Gaza Health Ministry is “a common move by those who seek to diminish the scale of civilian suffering in Gaza.”

Merchants of doubt

Nir Hasson reviewed the problems and half-truths in the document drawn up by researchers from the Begin-Sadat Center in a piece published earlier this month. He aptly categorizes their report as belonging to the category of so-called merchants of doubt, who employ a familiar denial tactic. Such people don’t necessarily deny that an event had occurred, however they use denial tactics to cast doubt on the data and generate alternative figures.

Powerful economic interests have exploited this method of denial – for example, tobacco companies disputing the link between smoking and cancer, and oil corporations challenging the reality of global warming. This is also the tactic used by deniers of the Armenian genocide and by Holocaust deniers. For his part, Faurisson measured the volume of the gas chambers and claimed it was physically impossible for them to hold the number of victims described in eyewitness accounts; therefore, he argued, genocide couldn’t be proven.

In a similar vein, the Begin-Sadat Center researchers calculate the Israel Defense Force’s use of munitions relative to the number of innocent casualties and conclude that proportionality can’t be judged solely by outcomes, even if these outcomes are tragic. In other words, even if the IDF has deployed an unreasonable level of firepower that has wiped out entire families, including infants and toddlers – that alone doesn’t mean that the force wielded was disproportionate. Put differently, a high civilian death toll doesn’t prove that a war crime was committed. What matters, according to the authors’ logic, is the military target itself.

Another common tactic of denial is to relativize the number of victims. The same authors argue that it’s impossible to determine the exact death toll in Gaza. Faurisson, similarly, argued that millions were not murdered in Auschwitz-Birkinau gas chambers – merely a few thousand who died of disease and epidemics in the camps.

Genocide does not require a single, explicit directive; rather, it’s the result of a process in which rhetoric, policy, political discourse, collective dehumanization and repeated patterns of action converge into mass acts of destruction.

But even if estimates of the number of victims in Gaza are reduced – say, to 30,000 innocent Palestinians – wouldn’t a killing on that scale still demand accountability? The very insistence on distilling the extent of such a crime to a precise figure is, among other things, a classic feature of genocide denial: an attempt to blur the atrocity through arithmetic.

The report by Orbach and his colleagues on Gaza, like the work of denialists before them, doesn’t present a genuine investigation, but rather a selective chain of arguments designed to preemptively dismiss any possibility of criminal charges being lodged against Israel for genocide. The framing may be more sophisticated than Faurisson’s crude denialism, however the objective is unmistakable: to deflect responsibility, blur legal and moral considerations, sow doubt and swap the ethical public debate for a technical one. In so doing, such an effort erects a wall between the atrocity and its true meaning – precisely the danger that Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide as the architect of the UN Genocide Convention, warned about: namely, the erasure of the identities and circumstances of victims’ deaths and replacement of them with numbers, definitions and statistical models.

This approach stands in stark contrast not only to Lemkin’s original definition of genocide, which emphasized the gradual, institutional and cultural destruction of ethnic groups, but also to later scholarly interpretations that stress the concept of “cumulative intent.”

Genocide does not require a single, explicit directive; rather, it’s the result of a process in which rhetoric, policy, political discourse, collective dehumanization and repeated patterns of action converge into mass acts of destruction.

When politicians claim that there are no innocents in Gaza, when an Israeli minister calls for dropping an atomic bomb on the Strip and others propose mass expulsions of a million residents or suggest separating men from women and children in order to eliminate them – this accumulated discourse becomes part of the machinery that enables and legitimizes actions on the ground.

Yad Vashem debacle

But the saddest chapter in Israel’s increasing tendency to deny the genocide in Gaza is reserved for Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority. The historians who work there and devote days on end to investigating the events of the Holocaust are choosing to silence their mouths and pens when it comes to the horrors of Gaza. In light of the flood of statements at the beginning of the war by Israeli politicians calling for mass killings there, a group of local scholars turned to Yad Vashem chairman Dani Dayan and requested that the institution publish a public condemnation of the declarations, specifically those calling for genocide. But in January 2024 Dayan replied to Prof. Amos Goldberg, who initiated the move: “The six million Jews who were murdered in the Shoah are entitled to an institution that deals with them and with them alone. Therefore, Yad Vashem doesn’t deal with genocide as such but only with its interface with the Shoah… Our area of activity is the Shoah, and only the Shoah.”

The comments written by the Yad Vashem chairman are unsettling not only because of his silence, but also because his words are wrapped in a cloak of ostensible institutional integrity, while turning an arrogant back to the sense of historic responsibility that is supposed to inform the memorialization of the Holocaust. “Six million Jews are entitled to an institution that deals with them alone,” writes Dayan – suggesting an exclusivity of the memory of murdered Jews as an excuse for hardheartedness, for closing one’s eyes and maintaining silence in the face of ongoing war crimes and tens of thousands of slaughtered and starved people. All part of the terrible crime being perpetrated by the descendants of another genocide, the Shoah, among others.

Wasn’t the murder of six million Jews also enabled due to many around the world washing away responsibility? Yad Vashem’s entrenchment in the claim that their expertise are limited to the Holocaust is an act of moral bankruptcy, of disavowal of responsibility based on institutional convenience and the ideological adoption of a governmental policy responsible for horrific war crimes. It is a dire betrayal of the values of liberty, justice and the sanctity of human life, which the memory of the Holocaust is supposed to teach us.

When a commemorative institution such as Yad Vashem chooses not only to remain silent, but to openly admit its decision to do so, it can no longer be regarded as an institution of memorialization. It becomes, willingly or not, an institution of self-righteousness and denial. And when heinous crimes are perpetrated only a few dozen kilometers away, by the same young people who visited the institution a few years back, and who are now being conscripted into the army, such silence isn’t neutrality, it’s complicity.

Turkish American sociologist Fatma Müge Göçek examines in her book, “Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present and Collective Violence Against the Armenians, 1789-2009” (2015), the roots of the denial of the Armenian genocide as a prolonged and ongoing psychosocial process. She asserts the denial is a psychosocial collective response, taking place across four generations of Turks, to dealing with an inconceivable crime.

Turkish society is suffering from profound moral dissonance. While witness to countless evidence attesting its own terrible crime, the society has conjured a collective narrative based on its being a victim – of wars, of Western imperialism, of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. This dynamic gives rise to a national identity whose defensive component – i.e., of rejecting blame – has become as formative as the memory itself.

For generations Turkey constructed a narrative of concealment, justification and silencing that not only drowned out the voice of the “others” (the Armenians), but also prevented the moral evolution of Turks themselves. This denial stems from a profound fear of the collapse of the national identity if the historical truth is acknowledged, and this fear is channeled into belligerence against anyone who tries to formulate a critical approach toward the crime.

For the past three generations Israel too has been constructing an identity of victimhood, ranging from acts perpetrated during the Holocaust to those of Hamas on October 7. It denies its own crimes and is therefore living in a permanently distorted reality. Any attempt to speak about Israel’s crimes against the Palestinians is seen as a threat not only to the image of the nation but to its very survival. The defensive narrative has become foundational to Israel’s national identity, and any criticism of this narrative is met with the kind of institutional and public violence we are witnessing today.

Prof. Daniel Blatman is a historian of the Holocaust and genocide.

This article is reproduced in its entirety