The powerful myth of Rabin

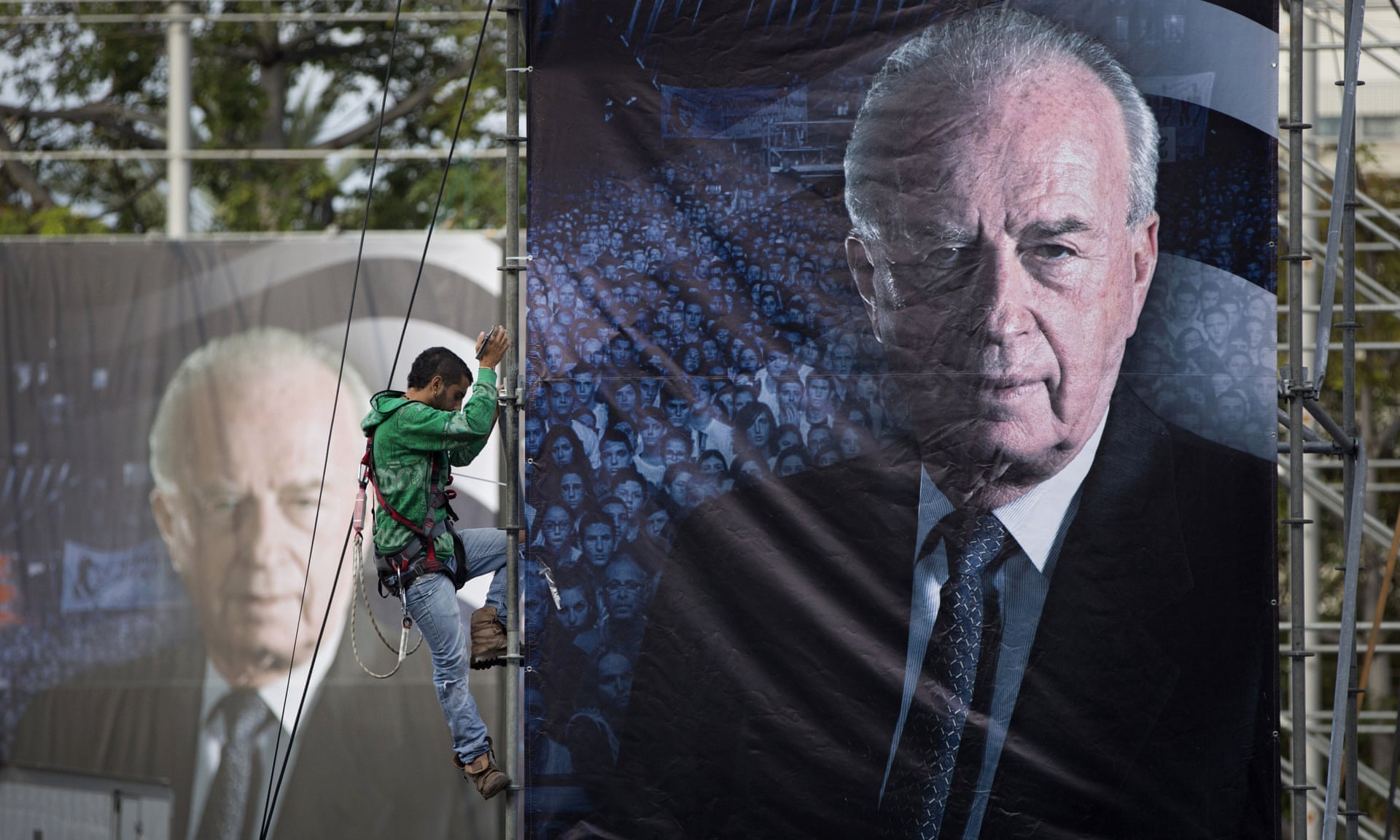

Preparing for the memorial rally in Tel Aviv, November 4th 2015. Photo by Oded Balilty/AP

Israel lost not just Yitzhak Rabin, but his politics of reason

Twenty years after his assassination, the Israeli leader’s eventual insight that there is no military solution to the Palestinian conflict is still missed

By Avi Shlaim, CiF, Guardian

November 02, 2015

On 4 November, 20 years ago, a Jewish fanatic assassinated the Israeli Labor party leader and prime minister Yitzhak Rabin. Rabin’s crime was to conclude a peace agreement with the PLO, hitherto regarded as a terrorist organisation pure and simple. Few political assassinations in history achieved their aim as fully as this one. The assassin’s aim was to derail the Oslo peace process and to halt the transfer of territory on the West Bank to the Palestinians. And this is what happened following the return to power of the rightwing Likud party.

Rabin was one of the most inarticulate prime ministers in Israel’s history. He had particular difficulty in putting down his thoughts on paper. Most of his speeches and articles were written for him by his aides. Consequently, there is not a single text with a clear exposition of his political creed. This does not mean, however, that he did not leave behind distinctive political legacy. He did and his legacy is ever more relevant in the context of the diplomatic standstill and rapidly escalating violence in Israel-Palestine today.

Rabin’s political legacy, in a nutshell, is that there is no purely military solution to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. This was not always his view, but something he learned from experience. Rabin was a soldier who turned to peacemaking relatively late in his political career. When the first Palestinian intifada broke out in 1987, Rabin was defence minister in a national unity government led by the Likud. His initial order to the IDF was to “break the bones” of the demonstrators. Only gradually did it dawn on him that this was in essence a political conflict that could only be resolved by political means.

After Labour won the election of 1992, Rabin acted on this premise and the result was the Oslo accord of 13 September 1993 and the hesitant handshake with Yasser Arafat on the lawn of the White House. This was the first ever agreement between the two main parties to the Arab-Israeli conflict: Israel and the Palestinians. The critics of the Oslo accord argue that it was doomed to failure from the start. My own view is that it was a modest step in the right direction, the beginning of the search for a political settlement to the bitter and prolonged conflict between the two rival national movements.

The assassin’s bullet put an end to this process. What might have happened had Rabin not been killed, there is no way of knowing. History does not disclose its alternatives. What is fairly clear is that the Oslo peace process broke down because, following the return of the Likud to power under the leadership of Binyamin Netanyahu in 1996, Israel reneged on its side of the deal.

Paradoxically, Rabin may yet go down in Israel’s history as the only true disciple of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the spiritual father of the Israeli right. Jabotinsky was the architect, in the early 1920s, of the strategy of “the iron wall”. The essence of this strategy was to deal with the Arab enemies from a position of unassailable military strength. The premise behind it was that an independent Jewish state in Palestine could only be achieved unilaterally and by military force.

There were two stages to this strategy. First, the Jewish state had to be built behind an “iron wall” of Jewish military power. The Arabs, predicted Jabotinsky, would repeatedly hit their heads against the wall until they despaired of defeating the Zionists on the battlefield. Then, and only then, would come the time for stage two: to negotiate with the Palestine Arabs about their status and rights in Palestine.

The politicians of the right have always been fixated on stage one of the “iron wall” strategy, on accumulating more and more military power in order to preserve the status quo, and keep the Palestinians in a permanent state of subservience. Netanyahu is a prime example of this approach. He is a reactionary status quo politician who has no interest in negotiations and compromise with the Palestinians and who now explicitly rejects a two-state solution. For him and his ilk, only Jews have historic rights over the whole “Land of Israel”. This makes him the proponent of the doctrine of permanent conflict.

Yitzhak Rabin was the first Israeli leader to move from stage one to stage two of the strategy of “the iron wall” in relation to the Palestinians. He practised what Jabotinsky had preached: he negotiated from strength and he went forward towards the Palestinians on the political plane. For him, at least in the twilight of his political career, military power was not an end in itself but a means to an end: a negotiated settlement of the century-old conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine. Rabin appreciated the value of military power but, unlike the politicians of the right, he also understood its limits. That is his true and enduring political legacy. It is as relevant today, when a third Palestinian intifada seems in the making, as it was 20 years ago.

Yitzhak Rabin’s daughter Dalia speaks at a ceremony marking the 20th anniversary of his murder. Photo by Debbie Hill/AFP/Getty Images

Anniversary of Yitzhak Rabin’s murder stirs what-ifs amid violence

Myth and reality abound 20 years on from assassination of Israeli prime minister who came close to forging durable reconciliation with Palestinians

By Ian Black in Jerusalem, The Guardian

October 26, 2015

In grim, reflective mood, Israelis are marking the 20th anniversary of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin – the prime minister who took a historic step towards peace with the Palestinians – linking his murder by a rightwing nationalist to the latest wave of Arab-Jewish violence and the bleak prospects for ending the conflict.

Rabin was honoured on Monday in ceremonies at the Mount Herzl cemetery in Jerusalem and in the Knesset, after President Reuben Rivlin solemnly pledged that his unrepentant killer, Yigal Amir, would never be released from prison. Many other events are taking place across Israel in the coming days.

In September 1993, Rabin signed the Oslo agreement with the PLO leader, Yasser Arafat, with President Bill Clinton watching their famously hesitant handshake on the White House lawn. It was a landmark in the century-long war over the Holy Land – though a controversial one that generated furious opposition on both sides.

But his murder at a peace rally in Tel Aviv on 4 November 1995 (the anniversary is marked according to the Hebrew calendar) was widely seen as a hammer blow to hopes that the interim deal, involving a partial Israeli withdrawal and the creation of a Palestinian Authority, could indeed lead the way to a just and lasting peace.

“Sadly, I have no news,” Rabin’s daughter, Dalia, said poignantly at her father’s graveside on Monday, in one of the memorial speeches broadcast live on TV. “There is no peace process. We are facing terrorism. Blood is being shed again. I have no other country and my country has changed.”

Rabin is remembered as a soldier, having expelled Palestinians en masse during the 1948 war and as chief of staff during the 1967 victory, when Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. But the general-turned-peacemaker was also the first Israeli political leader to be murdered – and, shockingly, by another Jew; not, as had always seemed more likely, by an Arab.

The 20th anniversary of his death has seen a torrent of comment against an unusually turbulent background: high tension over the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif site in East Jerusalem and the deaths of 50 Palestinians and 10 Israelis in the last month. Whether or not this constitutes a new intifada (uprising) or not, it has come as a vicious reminder of the intractable nature of the conflict and the persistence of the occupation – not to mention the hatred and desperation that can erupt when hopes for finding a solution die.

Binyamin Netanyahu, the Likud prime minister, made an immediate connection with the current violence. “I didn’t agree on everything with Yitzhak Rabin,” he told the Mount Herzl gathering. “Rabin wanted to end the conflict and he worked for peace, but he too was forced to deal with a cruel wave of terror. No knife, no stone, no petrol bomb or mine will stop us. We will never surrender to terrorism.”

In the mid-1990s, Netanyahu, then in opposition and a fierce opponent of the Oslo accord, was blamed for contributing to an atmosphere of incitement. Rightwing activists portrayed Rabin in SS uniform, while extremist, pro-settlement rabbis ruled that by talking to the PLO and ceding territory to Arafat, Rabin was a traitor – views that Amir used to justify his crime.

Much of the current discourse around Rabin’s death is about the danger of extremism in Israeli society. “The shots that killed him targetted the very essence of the sovereign Jewish state,” the thinker Prof Yedidia Stern commented in Haaretz this week. “The blood on the pavement was the blood of democracy itself.” Schools are holding classes on the meaning of political murder and the importance of tolerance.

Yet critics question the way Rabin is seen. “The main political forces in Israel today are the extreme settlers, and Rabin’s memory has nothing to do with them,” argued Tom Segev, one of Israel’s leading historians. “Rabin has become the poster boy for what Zionism and Israel have lost. He was the opposite of the fanatics. He was secular, pragmatic and sane. He was the last of the beautiful Israelis.”

Many clearly hanker after a more decisive prime minister than Netanyahu, whatever their views. “Israel needs a leader with Rabin’s DNA, who will act with faith and determination to reach an agreement,” said Uzi Baram, a former Labour minister.

Palestinians are sceptical. In 1987, when the first intifada erupted, Rabin was the defence minister who threatened to “break the bones” of the young stone-throwers confronting the occupation. “Rabin never wanted a Palestinian state,” insisted Mahdi Abdel-Hadi [L] of the Passia think-tank. “He played politics and worked with an isolated, corrupt Arafat. He wanted to contain the PLO, to tame the shrew. Oslo was an illusion. Israelis who believe it would have led to a real peace are indulging in wishful thinking.”

Palestinians are sceptical. In 1987, when the first intifada erupted, Rabin was the defence minister who threatened to “break the bones” of the young stone-throwers confronting the occupation. “Rabin never wanted a Palestinian state,” insisted Mahdi Abdel-Hadi [L] of the Passia think-tank. “He played politics and worked with an isolated, corrupt Arafat. He wanted to contain the PLO, to tame the shrew. Oslo was an illusion. Israelis who believe it would have led to a real peace are indulging in wishful thinking.”

But if the memory contains elements of myth, it remains a powerful one. On Monday evening, Israel’s Channel 2 TV broadcast an interview about Rabin with Clinton, who describes his devastation when the stunning news reached the Oval office. “My first thoughts were not even for the peace process,” the former US president said. “They were just for my friend. Then immediately I thought, ‘This could kill all his dreams.’”

Twenty years after Rabin’s death, Israelis and Palestinians agree on little. But many on both sides are certain that Oslo is dead, or in its dying days – with doubts growing that its institutional legacy, the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank under Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas, can survive much longer.

“Rabin probably stood a better chance of forging a durable reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians than any other leader before or since,” writes Dan Ephron* in Killing a King, a riveting new book about the prime minister and his murderer. “That we’ll never know how close he would have come is one of the exasperating consequences of the assassination.”

Note

For an extract from Killing a King and details of its publication, see

In the peace-killers’ twisted world