The Conflict In Maps

Many thanks to our friends at ICAHD for these fascinating and enlightening maps which throw light on the details of the infrastructure of the occupation. For a very detailed pre-partition 1946 map of Palestine see our previous posting. Also see links to other maps.

Recently added – Map of Jerusalem area showing proposed settlement development – as shown in the Times (4/04/09)

DESCRIPTIONS OF MAPS

Map 1: 1947 UN Partition of Palestine

The UN Partition Plan tried to divide the country according to demographic concentrations and national geography, but the Palestinian and Jewish populations were so intertwined that that became impossible. Although the Jews comprised only a third of the country’s population (548,000 out of 1,750,000) and owned only 6% of the land, they received 55% of the country (including both Tel Aviv/Jaffa and Haifa port cities, the Sea of Galilee and the resource-rich Negev). In the area allocated to the Jewish state, only about 57% of the population was actually Jewish (538,000 Jews, 397,000 Arabs). The Jewish community accepted the Partition Plan; the Palestinians (except those in the Communist Party) and the Arab countries rejected it.

Map 2: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories

By the end of the 1948 war – called the War of Independence by Israel and the Naqba (“Disaster”) by the Palestinians – Israel controlled 78% of the country, including half the territory that had been allocated by the UN to the Palestinians. Some 750,000 Palestinians living in what became Israel were made refugees or “internally displaced” people; under 200,000 remained in their homes. More than 418 villages, two-thirds of the villages of Palestine, were systematically destroyed by Israel after their residents had left or been driven out. Of the Arab areas, now reduced to 22% of the country, the West Bank was taken by Jordan and Gaza by Egypt. The 1949 Armistice Line, today known as the “Green Line,” de facto demarcates the State of Israel until today. Since 1988, when the Palestinians recognized Israel within that boundary, it has constituted the basis of the two-state option, with the Palestinians claiming a state on all the lands conquered by Israel in 1967: the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza.

Maps 3-7: Five Elements Defining the Palestinian Bantusan

Israel defines its policy of ensuring permanent control over the Occupied Territories as “creating facts on the ground.” In this conception, Israeli control must be made immune from any external or internal pressures to remove Israel from the Occupied Territories (which Israel vehemently denies is an occupation at all), as well as to foreclose forever the possibility of a viable and truly sovereign Palestinian state. Nevertheless, even Sharon recognizes that Israel needs a Palestinian state, since it can neither extend citizenship to the Territories’ three and a half million Palestinians nor deny it to them. It also needs a Palestinian state to relieve itself of the necessity of accepting the refugees. A Bantustan, a cantonized Palestinian mini-state controlled by Israel yet possessing a limited independence, thus solves Israel’s fundamental dilemma of how to keep control over the entire country yet “get rid of” its Palestinian population (short of actual “transfer”). The contours of that Bantustan are defined by five elements comprising Israel’s Matrix of Control as illustrated in the following maps: (1) Areas A and B; (2) the closure; (3) the settlement blocs; (4) the infrastructure; and (5) the Separation Barrier/Wall. A full (if complex) picture of the Matrix of Control is depicted in Map 10, and the truncated Palestinian mini-state Israel is creating in Map 11.

Map 3: Defining the Palestinian Bantustan. Element #1: West Bank Areas A, B and C

In the Oslo II agreement of 1995, the West Bank was divided into three Areas: A, under full Palestinian Authority control; B, under Palestinian civil control but joint Israeli-Palestinian security; and C, under full Israeli control. Although Area A was intended to expand until it included all of the West Bank except Israel’s settlements, its military facilities and East Jerusalem – whose status would then be negotiated – in fact the division became a permanent feature. Area A comprises 18% of the West Bank, B another 22%, leaving a full 60%, Area C, including most of Palestinian farmland and water, under exclusive Israeli control. These areas, comprising 64 islands, shape the contours of the “cantons” Sharon has proposed as the basis of the future Palestinian state. Taken together with Gaza, which Israel will relinquish, the emerging Bantustan will consist of five truncated cantons – a northern one around Nablus and Jenin; a central one around Ramallah; a southern one around Bethlehem and Hebron; enclaves in East Jerusalem; and Gaza. In this scheme Israel will expand from its present 78% to 85-90%, with the Palestinian state confined to just 10-15% of the country.

Map 4: Defining the Palestinian Bantustan. Element #2: The Closure and House Demolitions

At the very beginning of the Oslo peace process Israel established an ever-constrictive system of permanent “closure” over the Occupied Territories, a regime both arbitrary and counter-productive. Arbitrary because there was no particular rise in terrorism or security threats during this time; the security situation was certainly better than it was during the first Intifada, when there was no closure whatsoever. And counter-productive because, rather than benefiting the Palestinians, it meant that the “peace process” had actually impoverished and imprisoned them, destroying their commerce and industry and de-developing their emerging country. The permanent checkpoints depicted on the map, together with hundreds of other “flying” checkpoints erected spontaneously throughout the Territories and earthen barriers to the entrances to virtually all the Palestinian cities, towns and villages, present 600+ obstacles to Palestinian movement on any given day. They serve to accustom the Palestinians to living in a collective space defined by Areas A and B. When these cantons finally become a truncated Palestinian state, the Palestinians will already be adapted to its narrow confines. So minimal will be the Palestinians’ expectations that the addition of corridors linking the cantons will given them the feeling of “freedom,” thus leading them to acquiesce to the Bantustan. Israel’s policy of house demolitions, by which over 24,000 Palestinian homes have been demolished since 1967, is designed to confine the Palestinian population to the islands of A and B as well as small enclaves in East Jerusalem. (It is also a policy that impacts seriously on the Palestinian population within Israel.)

Map 5: Defining the Palestinian Bantustan. Element #3: Israel’s Settlement Blocs

When Ehud Barak proposed to “jump” to final status negotiations in 1999, he consolidated the settlements Israel sought to retain into “blocs,” leaving the more isolated and less strategic ones vulnerable to dismantling. Thus, instead of dealing with 200 settlements, Barak had only to negotiate the annexation of seven settlement blocs: (1) the Jordan Valley Bloc; (2) the Ariel Bloc that divides the West Bank east and west and preserves Israeli control over the Territories largest water aquifer; (3) the Modi’in Bloc, connecting the Ariel settlements to Jerusalem; a “Greater Jerusalem” consisting of (4) the Givat Ze’ev Bloc to the northwest of the city, (5) the expansive Ma’aleh Adumim bloc extending to the northeast and east of Jerusalem and (6) the Etzion Bloc to the southwest; and (7) a corridor rising from the settlements in the south to incorporate the Jewish settlements in Hebron. While the extent of these settlements blocs is to some extent subject to negotiations, their function, however, is to further define and divide the Palestinian cantons. Representing some 25% of the West Bank, their annexation to Israel has been approved by the US in the bi-lateral Bush-Sharon Exchange of Letters in April 2004. (Within the settlement blocs are depicted both the settlements themselves and the master plans that surround and extend them.)

Map 6: Defining the Palestinian Bantustan. Element #4: The Infrastructure of Control

In order to incorporate the West Bank and East Jerusalem permanently into Israel proper, a $3 billion system of highways and “bypass roads” has been constructed that integrates the settlement blocs into the metropolitan areas of Tel Aviv, Modi’in and Jerusalem, while creating additional barriers to Palestinian movement. This ambitious project articulates with the Trans-Israeli Highway, now being built along the entire length of the country, hugging the West Bank in its central portion. Shifting Israel’s population center eastward from the coast to the corridor separating Israel’s major cities from the settlement blocs it seeks to incorporate, the Trans-Israel Highway will become the new spine of the country, upon which the by-pass road network can be hung. The result is the reconfiguration of the country from two parallel north-south units – Israel and the West Bank, the basis of the two-state idea – into one country integrated east-west. Besides ensuring Israeli control, the reorientation of traffic, residential and commercial patterns further weakens a truncated Palestinian mini-state; each Palestinian canton is integrated separately into Israel, with only tenuous connections one to the other.

Map 7: Defining the Palestinian Bantustan. Element #5: The Separation Barrier/Wall

The final defining element of the bantustan is the Separation Barrier, known by its opponents as the Apartheid Wall both because it serves to make permanent an apartheid situation between Israelis and Palestinians, and because it rises to a massive concrete wall of eight meters (26 feet) when reaching Palestinian population centers – replete with prison-like watch towers, gates, security roads, electronic fences and deadly armaments. While sold to the public as an innocent security device, the Barrier in fact defines the border between Israel (including the areas of the West Bank and East Jerusalem Israel seeks to annex) and the Palestinian mini-state. It follows not the Green Line but establishes a new demographic line that extends Israel eastward into the West Bank. Although the Barrier’s overall route has been moved closer to the Green Line in light of the International Court of Justice’s ruling, the addition of “supplementary security zones” and “special security zones” to the Barrier’s complex still retains the convoluted route around the settlement blocs in order to ensure they are on the “right” side of the Barrier. When completed the Separation Barrier will be five times longer than the Berlin Wall (some 700 kms versus 155), in places twice as high and will unilaterally annex East Jerusalem and some 8% of the West Bank. As an installation costing over $3 billion, it is not designed to be dismantled.

Map 8: The Palestinian Bantustan in the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip is a tiny area of land 45 km (30 miles) long and 5-12 km (3-9 miles) in length, surrounded by Israeli settlements and electronic fences and gates. As of this writing – almost four years after Sharon’s plan of “disengagement” was completed – its 1.5 million Palestinian inhabitants live on just 139 square miless. Gazans, once farmers, are today impoverished, their lands cleared of fruit and olive trees and other crops as “security measures.” Some 75% of Gazans live on less than $2 a day, 80% are refugees living mainly in squalid camps. Gaza has one of the highest population densities in the world – 10,665 persons per square mile, almost four times the density of Bangladesh. Malnutrition among children is rampant; most of its water is taken by the settlers or is highly polluted; and more than 5,500 homes have been demolished and tens of thousands of more damaged in the course of the second Intifada and Operation Cast Lead. Gaza is divided into white, yellow, blue and green areas that divide Israelis and Palestinians. The settlements inside of Gaza have been removed, but post-“disengagement” Palestinians still live in a cage, blockaded by sea, fenced in by land, unable to travel by air, prevented from seeking employment in Israel.

When all the elements are put together, the full extent and complexity Israel’s Matrix of Control becomes evident. This raises the major question before us: Is the Occupation reversible? If it is not, if the Occupation can never be dismantled to the extent that a viable Palestine emerges, then should we continue supporting a “two-state solution”? To do so places us in a position of advocating for a Bantustan. If the Occupation is reversible, then we must ensure that the minimal conditions for a viable Palestinian state are achieved. In either case Israel’s “facts on the ground,” its Matrix of Control, are essential parts of the political equation.

Map 10: The Emerging Palestinian Bantustan in the West Bank

When the elements of the Matrix of Control are combined with American agreement for Israel’s annexing its major settlement blocs, the outlines of a Palestinian Bantustan clearly emerge. It is a mini-state of four islands occupying 10-15% of the country with no international borders, no territorial contiguity, no freedom of movement internally or externally, little economic viability, limited access to Jerusalem, no control of its water or other major resources, no control of its airspace or even its communications sphere, a demilitarized entity lacking even the authority to enter into foreign alliances without Israeli approval. If Israel has succeeded in rendering the Occupation permanent, it is not because of the logistical difficulties in removing the settlements. A Peace Now poll found that fully 90% of the settlers (most of whom live in the Territories for economic and “quality of life” reasons) would leave if they were offered comparable housing inside Israel. It is only the will if the international community to force the Israel government to abandon its settlement enterprise that is lacking. If that is the case, the international community is confronted with two stark choices: either to accept and condone a new apartheid situation, or to work towards another just and sustainable solution – a single democratic state in the entire country, a regional confederation or some other option. It is to be hoped that apartheid, the only “solution” Israel is offering by rendering its Occupation irreversible, will not be acceptable.

Map 11: Three Alternative Bantustans

The problem is not obtaining a Palestinian state. Israel itself desperately needs a Palestinian state, since it can neither bestow citizenship on the Palestinians nor deny it to them permanently. In order to retain its Jewish character yet control the entire country, Israel must somehow “relieve itself” of the Palestinian population. The only way out (except for transfer, which is impossible in the present circumstances) is to establish a Bantustan. Sharon has suggested a Bantustan (he calls it a plan of “cantonization”) on 40% of the West Bank, but has indicated that he is willing to unilaterally “give” the Palestinians 60%, perhaps even a bit more. Labor, wishing to make a Bantustan cosmetically acceptable, would offer up to 85% of the Occupied Territories, knowing that Israel needs just a strategic 15% to retain control.

Map 12: Moveable Borders: 1947, 1949, 1967 and On

These maps illustrate the changing borders at the expense of the Palestinians over the years. The picture that emerges is one of displacement, whether actually driving the Palestinians out of the country or confining them to a sort of reservations.

Map 13: Municipal Jerusalem, with the Separation Barrier

In 1967 Israel annexed an area of 70 sq. kms., which it called “East” Jerusalem, to the 38 sq. kms. that had comprised Israeli “West” Jerusalem since 1948, even though the Palestinian side of the city under Jordan was just 6 sq. kms. It gerrymandered the municipal border according to two principles: incorporating as much unbuilt-upon Palestinian land as possible for future Israeli settlements (the “inner ring” of settlements depicted in blue), while excluding as much of the Palestinian population as possible so as to maintain a 72% Jewish majority in the city. As the concentrations of Palestinian population show (in brown), the municipal border cut in half a living urban fabric of communities, families, businesses, schools, housing and roads. Its placement of settlements prevents the urban development of Palestinian Jerusalem – the economic and cultural as well as religious center of Palestinian life – transforming its residential and commercial areas into disconnected enclaves. There are today more Israelis living in “East” Jerusalem (more than 200,000) than Palestinians. Since Palestinians cannot live in “West” Jerusalem, Israeli restrictions on building (combined with an aggressive campaign of house demolitions) have confined that population to a mere 6% of the urban land – although they are a third of the Jerusalem population. Discriminatory administrative and housing measures have led to the “Quiet Transfer” of thousands of Palestinian families out of the city, and to the loss of their Jerusalem residency.

Map 14: The Three Jerusalems: Municipal, Greater and Metropolitan

The “inner ring” of settlements that defines municipal Jerusalem is today being linked with an “outer ring” of settlements to transform Jerusalem from a city into a region that controls the entire central portion of the West Bank. “Greater Jerusalem,” the master plan of which was formalized already in 1995, extends the city far into the West Bank. Yet an even more extensive “Jerusalem” exists: Metropolitan Jerusalem. Though not intended for annexation, it forms a planning unit designed to ensure that Ramallah and Bethlehem remain undeveloped satellite cities dependent upon Israeli Jerusalem even if they eventually fall across a political border separating Israel from Palestine. Indeed, by creating extensive buffer zones between the city of Jerusalem and the surrounding West Bank, Israel is eliminating the economic heart of any Palestinian state. In this way Israel keeps all the developmental potential of the city — and the country as a whole – firmly in its hands, rendering the Palestinian state a non-viable entity existing on a Third World subsistence level.

The map also shows the “E-1” area, 4000 acres annexed to Ma’aleh Adumim in a combined move by the Netanyahu and Barak governments. With the addition of E-1, Ma’aleh Adumim’s master plan extends entirely across the West Bank from Jerusalem to Jericho, effectively severing the northern West Bank from the south. Palestinian traffic will likely be diverted into Israeli territory (along the “Eastern Ring Road” now being constructed in East Jerusalem), allowing Israel to control Palestinian movement even in the event that a Palestinian state emerges. E-1 reveals the subtle, sophisticated and effective use of planning for control employed by Israel.

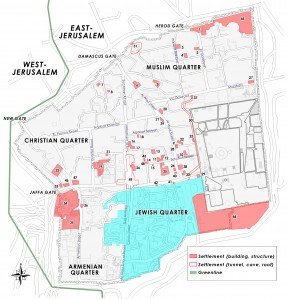

Map 15: The Colonization of Jerusalem’s Old City

The settler movement has long had its eyes set on increasing Jewish control inside the Old City of Jerusalem. Few parts of the Old City are without settler encroachment. Even Damascus Gate, the famous entrance to the Muslim Quarter, is framed with settlements including a house owned by former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon (No. 6 on the map).

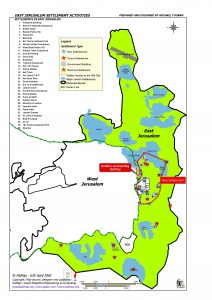

Map 16: Settlement activity in East Jerusalem

The Israeli government, the Municipality of Jerusalem, and settler organizations are working to strengthen the control settlements and Israeli infrastructure have in East Jerusalem. Individual properties are bought, stolen and confiscated by settlers and large swaths of land are expropriated by the government for new, large settlements. Just as the government wants to establish facts on the ground with settlements surrounding East Jerusalem, so too do the East Jerusalem settlements movements, led by the Elad and Ateret Cohanim groups, wish to surround the Old City of Jerusalem with a sufficiently dense Jewish population to prejudice the status of the land in future negotiations.