Stop there! You have no right to move

Notes on the Civil Administration and international law on the right to freedom of movement at foot.

Palestinians from the village of Beita hold Friday prayers at an Israeli military roadblock in protest at this collective punishment, September 23, 2016. Photo by Ahmad Al-Bazz / Activestills.org

From B’Tselem

30 Oct 2016

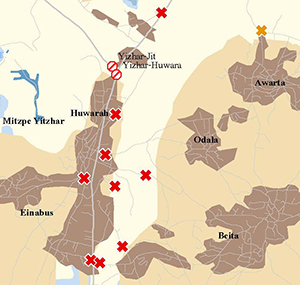

From 4 to 11 September 2016, the military blocked the entrances to ten Palestinian communities in the south of Nablus District, along the Huwara road. The military also blocked several roads used to access farmland and side roads. This came on top of the regular closure of the main entrance to ‘Awarta, imposed by the military since the killing of Eitam and Naama Henkin in a terror attack in October 2015. These restrictions disrupted the lives of some 54,000 residents in the area. The Israeli authorities informed the Palestinian DCO [District Coordination Office] , operating in the West Bank. that the reason for the roadblocks was the throwing of a Molotov cocktail at an Israeli vehicle in the area.

The restrictions were removed as part of the “relaxations” agreed by Israel to mark the Muslim festival of ‘Eid al-Adha. However, a few days later, on 20 September, the restrictions were reinstated, and side roads and dirt tracks that had been used as an alternative to the main roads two weeks earlier were also blocked. The Palestinian DCO notified the heads of the local Palestinian councils that the second closure followed the throwing of stones at an Israeli bus near Huwara. The restrictions were removed on 26 September.

Map of Roadblocks in southern Nablus District, Sept. 2016

The Palestinian communities to which access was blocked were defined in the Oslo Accords as Area B, which is under the administrative responsibility of the Palestinian Authority. These are small communities whose residents depend on the regional centre – Nablus – for their routine needs. Many of them work or study in the city and receive various services there, including healthcare. The restrictions forced the residents to use roundabout and even dangerous routes. Ambulances traveled along uneven surfaces; patients and elderly people were forced to walk long distances by foot; teachers were delayed on their way to school; physicians missed scheduled appointments with patients; and women, men, and children had to wait for taxis willing to take the roundabout routes.

These traffic restrictions lengthened the time needed to travel to Nablus and other communities in the district by 20 to 40 minutes, and also caused a hike in transportation costs. Public transportation in the area is based mainly on shared taxis, and the cost of a journey between Nablus and most of the communities in the area is usually in the range of NIS 5-10 (USD 1.5-2.5). Following the road closures, many of the shared taxis stopped operating and residents were forced to use private taxis at a significantly higher cost.

The restrictions, imposed without any prior warning, created a state of uncertainty among all the residents of the area, who had no way of knowing which roads had been closed, how long it would take them to reach their destination, and when the military planned to remove the restrictions. This action constituted the collective punishment of tens of thousands of people. It also refutes Israel’s claim that large sections of the West Bank have been transferred to the control of the Palestinian Authority and that it does not manage these areas. As this affair shows, Israel can all too easily disrupt the lives of tens of thousands of Palestinians, while the Palestinian Authority has no ability to influence or intervene in these actions.

On 21-22 September 2016, Salma a-Deb’i, B’Tselem’s field researcher in the Nablus area, collected testimonies from residents of the area, who described the difficulties they faced due to the restrictions:

Roadblock placed by the military across the entrance to ‘Einabus. Photo by Salma a-Deb’i, B’Tselem, 4 September 2016

Fawzeyeh ‘Ata ‘Ali Qawariq, diabetic patient, 62, resident of ‘Awarta, stated in her testimony:

On Tuesday, 20 September 2016, at about three o’clock at night, my daughter Su’ad told me that they had blocked the entrance to our town, and to several other villages in the area, with dirt piles. I became anxious when I heard this, because I have diabetes and I had an appointment at the medical clinic scheduled for that day. It’s a monthly appointment that I must keep, because I have to undergo tests and get new prescriptions for medicines. I left home at eight in the morning and got on a shared taxi. It took a roundabout route along a farmers’ road through Huwara Valley, and the journey was very slow. It took us half an hour to get from Huwara to Odala, a trip that usually takes ten minutes.

When I got to the clinic, the nurse took my blood pressure as usual and told me that it was high. I told her that I had been anxious because of the closure of the road and had been sitting since dawn wondering how I would get to the clinic. I took the medication and went home by the same difficult route. I couldn’t understand why they were doing this to us.

I’m very worried about the situation, because my husband also needs to go to Nablus several times a week for treatment. He has a number of medical problems, including a heart problem and urinary failure, and traveling along these roads is very difficult for him.

The restrictions also harm my sons, who work in Israel and in Huwara and have to struggle along these roads to get to their places of work. If they arrive late it causes problems with their work. No-one here can understand why they are closing the roads.

Where do they want us to go? They ignore the fact that people live here and need to go places for their daily needs – for our livelihood, health, and our very existence.

Roadblock placed by the military at the entrance to Odala. Photo by Salma a-Deb’i, B’Tselem, 4 September 2016

Dalal Mahmud Hassan Faqha , 43, science teacher and resident of Deir Sharaf, described her difficulties reaching work:

I am a science teacher at a co-ed school in Burin. I usually travel to Nablus in the morning, and then continue on to the school with my colleagues. Because of the restrictions, we had to leave half an hour early and try to travel through the villages of Tell and Madama, since we were afraid that the entrance to Burin was blocked.

We have suffered from traffic restrictions since 2000. Every time they set up roadblocks, impose restrictions, and close roads. Because I have to leave early in the morning, I don’t have time to make breakfast for my children or spend time with them. I get up at 5:50 A.M. and leave home quickly in order to get to Nablus and then to my workplace in Burin. All the way I am nervous and afraid that I won’t manage to meet my colleagues in Nablus and join the ride. When that happens, I have to take a taxi, and when restrictions are imposed it’s very difficult to find a place in a taxi.

Feeling that your movement is limited is very disturbing. You don’t know how you will get to work or back home.

I’m not interested any more in the reasons for the road closures. No one talks about that. They only talk about how to cope with the situation, get to work, make a living, and get back home. It doesn’t serve any goal other than punishing and humiliating us for no reason.

Roadblock placed by the military at the entrance to Beita. Photo by Salma a-Deb’i, B’Tselem, 4 September 2016

Yusef Musa Muhammad Diriyah, 40, ambulance driver and resident of ‘Aqraba, described how the restrictions endanger patients’ lives:

I am an ambulance driver at the trauma center in ‘Aqraba. The old eastern entrance to the village (the ‘Aqraba-‘Awarta road) has been closed since 2000. Now, since the restrictions were imposed, the main entrance to the town is also closed. The road through Beita can’t be used either, because the entrance to Beita is blocked. Since the restrictions were imposed at the beginning of the month, the only way to our town is through Osarin. This is a difficult and winding road and even in emergencies we cannot drive fast, because it’s really dangerous. We are responsible not only for the ‘Aqraba area, but also for trauma cases, diseases, and road accidents throughout the southern part of Nablus District. There are a lot of wild boars in the southern Nablus area, and this causes road accidents. Using this road delays our work and exposes us, our patients, and other passengers along the way to danger. The only alternative to Osarin is the road through Majdal Bani Fadel, in the opposite direction. It feels as if we and the whole area are under siege.

Before ‘Eid al-Adha, when the roads were closed, the Red Crescent station in Nablus sent me to pick up a patient in the village of Beita. I drove along the Beita-‘Aqraba road and reached the patient, who was showing symptoms of a stroke. I evacuated him in the ambulance up to the earth barrier at the main entrance to Beita, and waited there for a Red Crescent ambulance. They transferred the patient from to their ambulance on a stretcher. If this had been a situation requiring an urgent response, such as a road accident or fire, we would really have had a problem.

NOTES

The Civil Administration operates through nine Israeli District Coordination Offices (DCO) in the West Bank. They are an arm of COGAT, the Israeli governing body in the West Bank which is part of the Ministry of Defence.

Freedom of movement, mobility rights, or the right to travel is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country, and to leave the country and return to it. The right includes not only visiting places, but changing the place where the individual resides or works.

Such a right is provided in the constitutions of numerous states, and in documents reflecting norms of international law. For example, Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts that:

- a citizen of a state in which that citizen is present has the liberty to travel, reside in, and/or work in any part of the state where one pleases within the limits of respect for the liberty and rights of others,

- and that a citizen also has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country at any time.

from Wikipedia