Should intellectual products be exempt from boycott?

The most recent issue of the Journal of Academic Freedom, the American university professors’ publication, is devoted to the question of Israel and academic boycott. We post three of the contributions below – by Joan Scott, Omar Barghouti and David Lloyd and Malini Johar Schueller. In Notes and links are the table of contents of the issue, and details of the forthcoming conference, organised by Independent Jewish Voices, Beyond the Stalemate: the ongoing Palestinian-Israeli impasse at which Mustafa Barghouti, General Secretary of the Palestine National Initiative (PNI), is the keynote speaker on October 13th.

Protest in Melbourne, 2010

Changing My Mind about the Boycott

By Joan W. Scott, AAUP

September 2013

In 2006, I was one of the organizers of an aborted AAUP conference on academic boycotts. The point was to open a conversation about the utility—past and present—of such political actions, to understand what was actually involved in the choice of that strategy, to conduct a conversation in a setting above the fray (in this instance at the Rockefeller Conference Center in Bellagio, Italy), and to learn what we could from the various points of view we hoped to represent at the conference. Idealistically, we imagined the conference to be an exercise in academic freedom, the fulfillment of the best of AAUP principles. In fact, our experience was anything but the fulfillment of AAUP ideals. From the outset, defenders of right-wing Israeli politics—with Professor Gerald Steinberg of Bar-Ilan University in the lead—sought to prevent the meeting, arguing, in the name of academic freedom, that “illegitimate” (that is, Palestinian) voices would be included in the group. Soon the then-leaders of the AAUP—Cary Nelson and Jane Buck—joined the opposition, notifying the funders of the conference that it did not have official AAUP approval. (They did not notify the conference organizers of these actions.) At that point the conference was canceled. The full story, as well as some of the papers that would been presented at the conference, was published in a special report in Academe (September–October 2006).

Those of us who organized the conference were not promoting academic boycotts; we were simply interested in debating the issue in order to better understand and evaluate the strategy of the boycott. In fact, at the time, I agreed with the prevailing view at the AAUP that academic boycotts were contrary to principles of open exchange protected by academic freedom. I have now reconsidered that view. Even at the time, in the heat of the controversy about our conference, it began to seem to me that inflexible adherence to a principle did not make sense without consideration of the political contexts within which one wanted to apply it. Indeed, given the vagueness of the principle of academic freedom, its many different uses and applications, knowing how to apply it required understanding the different functions it served in practice. If the conference was meant to achieve that understanding, it was thwarted, for we had clearly walked into a political minefield—the so-called defenders of Israel were going to prevent us from exercising our rights to free speech (to discussion and debate), just as they were preventing their critics within Israel from doing the same by threatening and firing those who represented dissenting views. What did it mean, I wondered, to oppose the boycott campaign in the name of Israeli academic freedom when the Israeli state regularly denied academic freedom to critics of the state, the occupation, or, indeed, of Zionism, and when the blacklisting of the state’s critics is the regular tool of state authorities against Israel’s own academic institutions?

If anything, the power of the Right and the oppression of Palestinians have increased since 2006—even the supposed “weakening” of the Netanyahu government has taken place through the strengthening of right-wing parties. The country that claims to be the only democracy in the Middle East is putting in place a brutal apartheid system; its politicians are talking openly about the irrelevance of Arab Israeli votes in elections and developing new methods for testing Arab Israeli loyalty to the Jewish state. Israel’s legal system rests on the inequality of Jewish and nonJewish citizens; its children are regularly taught that Arab lives are worth less than Jewish lives; its military interferes with Palestinians’ access to university education, freedom of assembly, and the right to free speech; and its Council of Higher Education, now an arm of the Likud Party, has elevated a religious college in the settlements to the status of a university, accrediteda neoconservative think tank to grant BA degrees to students, and conducted inquisitions among university faculty, seeking to harass, demote, or fire dissidents—that is, to silence their speech. The hypocrisy of those who consider these to be democratic practices needs to be exposed. An academic and cultural boycott seems to me to be the way to do this.

Such a boycott refuses to accept the facade of democracy Israel wants to present to the world. It is not a boycott of individuals on the basis of their national citizenship. Quite the contrary—it is an institutional boycott, aimed at those cultural and educational institutions that consistently fail to oppose the occupation and the unequal treatment of non-Jewish citizens. It demands evidence that these institutions provide academic freedom to Arabs as well as Jews, Palestinians as well as Israelis, within the borders of Israel, the occupied West Bank, and Gaza, and support it for Arabs and Jews equally. It says that, in the face of an apartheid that violates both the principles and practices of equality and freedom for all, a principled opposition to boycotts as punitive or unfair makes no sense. In fact, such an opposition only helps perpetuate the system. The boycott is a strategic way of exposing the unprincipled and undemocratic behavior of Israeli state institutions; its aim might be characterized as “saving Israel from itself.”

The American academy has been particularly complicit in perpetuating the fiction of Israeli democracy—its leaders seek to protect Israel from its critics, even as they also seek to protect themselves from the wrath of the organized lobbies who speak on behalf of the current Israeli regime and its policy of establishing academic outposts in illegal settlements. This, it seems to me, is ill advised, since so much of Israeli politics right now is at odds with the best values of the American educational system. Paradoxically, it is because we believe so strongly in principles of academic freedom that a strategic boycott of the state that so abuses it makes sense right now.

Joan W. Scott is Harold F. Linder Professor in the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. Her most recent book is The Fantasy of Feminist History (2011).

Boycott, Academic Freedom, and the Moral Responsibility to Uphold Human Rights

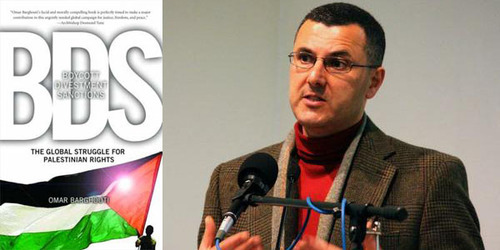

By Omar Barghouti [above]

In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order, and the general welfare in a democratic society.

—United Nations, “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” (1948), Article 29(2)

Discrimination at every level of the [Israeli] education system winnows out a progressively larger proportion of Palestinian Arab children as they progress through the school system—or channels those who persevere away from the opportunities of higher education. The hurdles Palestinian Arab students face from kindergarten to university function like a series of sieves with sequentially finer holes.

—Human Rights Watch, “Second Class: Discrimination against Palestinian Arab Children in Israel’s Schools” (2001)

Just before year end 2012, Israeli defense minister Ehud Barak signed the official document upgrading the colony-college of Ariel, built on occupied Palestinian land, to a university, inviting unprecedented condemnation. Many academics around the world had already joined the widespread silent academic boycott of Israel—that is, the unannounced, yet very effective, shunning of academic visits to and relations with Israeli academic institutions—well before this latest upgrade of Ariel. After the upgrade, what started as a trickle may well develop into a South Africa–style deluge of academic boycotts against Israel.

Yet the focus on settlement institutions should not ignore or obscure the fact that allIsraeli academic and cultural institutions are deeply complicit in maintaining the system of occupation and denial of basic Palestinian rights and are therefore just as worthy of the boycott. Not to recognize this would be to miss the forest for the trees. For example, in April 2005, the annual congress of the British Association of University Teachers (AUT) adopted a resolution calling for the boycott of two Israeli universities, BarIlan and Haifa, for various infringements, and asking AUT members to heed the call of the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI).

In response, the AAUP issued a curt report condemning academic boycotts as inherently antithetical to academic freedom.

Three sets of problems arise from the AAUP stance on this issue: the conceptual, the functional, and the ethical. Together, they pose a considerable challenge to the coherence of the AAUP’s position on the academic boycott of Israel, and they call into question the consistency of this position with the organization’s long-standing policies and modes of intervention in cases where its principles are breached. Most important, by positing its particular notion of academic freedom as being of “paramount importance,” the AAUP effectively, if not intentionally, sharply limits the moral obligations of scholars in responding to situations of serious violations of human rights. This essay deals with the conceptual and ethical shortcomings of the AAUP position.

Conceptual Inadequacy

The AAUP’s conception of threats to academic freedom appears to be restricted to intrastate onflicts, mainly “governmental policies” that suppress the “free exchange of ideas among academics.” For example, a governmental decree in China institutionalizing censorship of academic publications would fall in this category. This leaves out academics in contexts of colonialism, military occupation, and other forms of national oppression where “material and institutional foreclosures . . . make it impossible for certain historical subjects to lay claim to the discourse of rights itself,” as philosopher Judith Butler eloquently argues. Academic freedom, from this angle, becomes the exclusive privilege of some academics but not others.

Moreover, by privileging academic freedom above all other freedoms, the AAUP’s notion contradicts seminal international norms set by the United Nations. The 1993 World Conference on Human Rights proclaimed, “All human rights are universal, indivisible . . . interdependent and interrelated. The international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis.”

Finally, by turning the free flow of ideas into an absolute, unconditional value, the AAUP comes into conflict with the internationally accepted conception of academic freedom, as defined by the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (UNESCR), which states:

Academic freedom includes the liberty of individuals to express freely opinions about the institution or system in which they work, to fulfill their functions without discrimination or fear of repression by the state or any other actor, to participate in professional or representative academic bodies, and to enjoy all the internationally recognized human rights applicable to other individuals in the same jurisdiction. The enjoyment of academic freedom carries with it obligations, such as the duty to respect the academic freedom of others, to ensure the fair discussion of contrary views, and to treat all without discrimination on any of the prohibited grounds.

When scholars neglect or altogether abandon such obligations, when they infringe on the “academic freedom of others,” they can no longer claim what they perceive as their inherent right to this freedom. This rights-obligations equation is the general underlying principle of international law in the realm of human rights. It also was one of the foundations of the AAUP’s initial view of academic freedom, as expressed in its 1915 Declaration of Principles, which conditioned this freedom on “correlative obligations” to further the “integrity” and “progress” of scientific inquiry. Without adhering to a set of inclusive and evolving obligations, academic institutions and associations have little traction to discourage academics from engaging in acts or advocating views that are deemed bigoted, hateful, or incendiary.

Should a professor be free to write, “Among [Jews], you will not find the phenomenon so typical of [Islamic-Christian] culture: doubts, a sense of guilt, the self tormenting approach. . . . There is no condemnation, no regret, no problem of conscience among [Israelis] and [Jews], anywhere, in any social stratum, of any social position”? In fact, if we substitute for the words in brackets—in order—“Arabs,” “Judeo-Christian,” “Arabs,” and “Muslims,” the above becomes an exact quotation from a book by David Bukay of Haifa University. A Palestinian student of Bukay’s filed a complaint against him alleging racially prejudiced utterance. The university’s rector exonerated Bukay of any wrongdoing, although Israel’s deputy attorney general ordered an investigation of Bukay “on suspicion of incitement to racism.”In this case, the institution itself becomes implicated.

Criminal law aside, should an academic institution tolerate, under the rubric of academic freedom, a hypothetical lecturer’s advocacy of the “Christianization of Brooklyn,”say, or some “scientific” research explicitly intended to counter the “Jewish demographic threat” in New York? Arnon Soffer of Haifa University has worked for years on what is exactly the same, the “Judaization of the Galilee,” and he is launching projects aimed at fighting the perceived “Arab demographic threat” in Israel.11 In his university and in the Israeli academic establishment at large, Soffer is highly regarded and often praised.

Do academics who uphold Nazi ideology, deny the Holocaust, or espouse anti-Semitic theories enjoy the right to advocate their views in class? Should they? Does the AAUP notion of academic freedom have the competence to consistently address such thorny cases?

British Ambassador to Israel Matthew Gould receiving an honorary doctorate from Ben Gurion University of the Negev in December 2012. He used his speech to criticize academic boycotts and praise Israeli universities for their excellence. Photo by Dani Machlis/Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Ethical Responsibility

The AAUP report “On Academic Boycotts” asks, “If there is no objective test for determining what constitutes an extraordinary situation, as there surely is not, then what criteria should guide decisions about whether a boycott should be supported?” (emphasis added). While “objective” criteria may indeed be an abstract ideal that one can strive for without ever reaching, some ethical principles have acquired sufficient universal endorsement to be considered relatively objective, at least in our era. Prohibitions against committing acts of genocide and against murdering children are two obvious examples. The growing body of UN conventions and principles must be considered the closest approximation to objective criteria to guide us in adjudicating conflicts of rights and freedoms, particularly in situations of oppression.

UN norms and regulations may not be wholly consistent among themselves, but they are mostly informed by the ultimate ethical principle of the equal worth of all human lives and the indivisibility and interdependence of human rights to which every human being has a claim. Arguably, the violation of these principles was the strongest motivation behind the AAUP’s laudable call for divestment from South Africa during apartheid. This precedent is worth highlighting, as it deals with criteria, implicit though they may be, for deciding what constitutes an “extraordinary situation” necessitating exceptional measures of intervention.

The AAUP’s support for a form of boycott against apartheid-era South Africa can be interpreted or extrapolated to show that when a prevailing and persistent denial of basic human rights is recognized, the ethical responsibility of every free person and every association of free persons, academic institutions included, to resist injustice supersedes other considerations about whether such acts of resistance may directly or indirectly injure academic freedom. This does not necessarily mean that academic freedom is relegated to a lower status among other rights. It simply implies that in contexts of dire oppression, the obligation to help save human lives and to protect the inalienable rights of the oppressed to live as free, equal humans acquires an overriding urgency and an immediate priority. This is precisely the logic that has informed the call for boycott issued by PACBI in 2004.

PACBI’s Institutional Boycott

Unlike the South African academic boycott, the Palestinian call for an academic boycott of Israel is institutional in nature; it specifically targets Israeli academic institutions because of their complicity, to varying degrees, in planning, implementing, justifying, or whitewashing Israel’s occupation, racial discrimination, and denial of refugee rights. This collusion takes various forms, from systematically providing the military-intelligence establishment with indispensable research—on demography, geography, hydrology, and psychology, among other disciplines—that directly benefits the occupation apparatus to tolerating and often rewarding racist speech, theories, and “scientific” research; institutionalizing discrimination against Palestinian Arab citizens; suppressing Israeli academic research on the Nakba, the catastrophe of dispossession and ethnic cleansing of more than 750,000 Palestinians and the destruction of more than four hundred villages during the creation of Israel; and directly committing acts that contravene international law, such as the construction of campuses or dormitories in the occupied Palestinian territory, as Hebrew University has done, for instance.

Accordingly, although the ultimate objective of the boycott is to bring about Israel’s compliance with international law and its respect for Palestinian human and political rights, PACBI’s targeting of the Israeli academy is not merely a means to an end but rather a part of that end. In other words, the boycott against Israel’s academic institutions—one component of the general campaign for boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS)14 against Israel—not only aims at indirectly undermining Israel’s system of oppression against the Palestinians but also directly targets the academy itself as one of the pillars of this oppressive order.

Regardless of prevailing conditions of oppression, the AAUP has been consistent in opposing academic boycotts, preferring only economic boycotts and those only in extreme situations. In justifying its preference, the AAUP argues, among other points, that an academic boycott injures blameless academics. But does an economic boycott not hurt many more innocent bystanders, and not just in the academic community? Boycott is never an exact science, if any science is exact. Even when focused on a legitimate target, it invariably causes injury to others who cannot with any fairness be held responsible for the disputed policy. The AAUP-endorsed economic boycott of South Africa during apartheid certainly resulted in harm to innocent civilians, academics included. But as in the South African boycott, rather than focusing on the “error margin,” as important as it is, proponents of the boycott of Israel, while doing their utmost to reduce the possibility of inadvertently hurting innocent individuals, must emphasize the emancipating impact that a comprehensive and sustained boycott can have not only on the lives of the oppressed but also on the lives of the oppressors.

As South African leader Ronnie Kasrils and British writer Victoria Brittain have argued,

“The boycotts and sanctions ultimately helped liberate both blacks and whites in South Africa. Palestinians and Israelis will similarly benefit from this nonviolent campaign that Palestinians are calling for.”

The Israel boycott, in this light, can be a crucial catalyst for processes of transformation that promise to bring us closer to realizing a just and durable peace anchored in the fundamental and universal right to equality.

Omar Barghouti is an independent researcher, a founding member of PACBI and the BDS movement, and the author of Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions: The Global Struggle for Palestinian Rights (Haymarket, 2011).

The Israeli State of Exception and the Case for Academic Boycott

By David Lloyd and Malini Johar Schueller

Since the initial call for an academic and cultural boycott of Israel issued by Palestinian intellectuals in October 2002, the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI), launched in April 2004, has been perhaps the most significant element in an international and growing movement for boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) against Israel. Endorsed by over 170 Palestinian organizations, including the Federation of Unions of Palestinian Universities’ Professors and Employees, BDS and PACBI are widely popular, nonviolent means to pursue the end of a regime of occupation, siege, dispossession, and discrimination that Israel has imposed with almost complete impunity for decades. A rights based campaign that calls on civil society internationally to seek redress for gross violations of international law and human rights in the face of governments’ refusal to act, PACBI has called for an institutional boycott, that is, a boycott not of individual academics or artists but of educational and cultural institutions whose complicity in the maintenance and furtherance of occupation is indubitable and continuing.

It also calls for the boycott of institutions or cultural organizations that operate explicitly under the auspices of the Israeli state, as ambassadors who seek to normalize the occupation and to promote a benevolent image of Israel as part of its campaign of propaganda (hasbara).

Despite the AAUP’s history of censuring governments and institutions for violations of academic and intellectual freedoms, and despite the principled stand that it took against South African apartheid in supporting the divestment campaign, it has to date refused to endorse PACBI’s call for an academic boycott. The grounds that it has given publicly for this refusal are so confused and inconsistent with past policy and practice that we must again clarify the rationale for the boycott and question the exceptional exoneration that the AAUP grants to Israel alone among states.

A boycott is a nonviolent instrument that both expresses disapproval of the prolonged conduct of a person or institution that injures others and withdraws material support for that person or institution so long as they persist in such conduct. It is generally called for and applied by those to whom other means of action are denied. That said, a boycott is a specific tactic, deployed in relation to a wider campaign against injustice and under quite determinate circumstances. It should not be exercised indiscriminately in ways that would inevitably be ineffective. The optimal conditions for applying a boycott as a tactic include the following:

a. The entity aimed at must be vulnerable to a boycott as a result of its connections with, or dependence on, the nations whose publics boycott it. An economic boycott of the European Union, the United States, or China, for example, would probably be economically ineffectual and thus politically futile, much as we might desire such boycotts in principle.

b. There must be a relatively open public sphere in the nation boycotted in order for its citizens to influence their leaders, and the boycotted nation’s citizens must care about the opinion of those boycotting them. This is the case with Israel, as it was with South Africa, since their populations largely wish to be counted among “civilized” or “democratic” Western nations. In both cases the campaign for a cultural and academic boycott exerts more impact than economic sanctions: it goes directly to citizens’ sense of integration in the global cultural community. This is not to say that either South Africa was or that Israel is ademocracy in any meaningful sense of the word: apartheid systems function precisely by claiming democratic rights for only a part of their population, and systematically denying those rights to the subordinated remainder.

c. The boycott should be explicitly supported by the occupied or oppressed people concerned, who often stand to suffer most from the consequences of its application. This was the case with the divestment campaign against South Africa, called for by the African National Congress (ANC), and is the case with BDS against Israel.

d. The boycott must make demands that are realizable by the nation boycotted, like conforming to international law, ending an occupation or blockade, dismantling a racist or apartheid system, negotiating in good faith, and so on. BDS invokes three summary principles, in conformity with the norms of human rights conventions and international law.

Israel must:

1. End its occupation and colonization of all Arab lands, end the siege of Gaza, and dismantle the segregation wall;

2. Recognize the fundamental rights of the Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality;

3. Respect, protect, and promote the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in UN Resolution 194.

e) Finally, a boycott should be based on nonviolent principles, and thus implies a rejection by those engaging in the boycott of the resort to violence. The Palestinian BDS campaign is expressly opposed to all forms of racial, religious, gender, or other discrimination, universally, which accords with its insistence on Israel’s coming into conformity to international law and human rights conventions.

To what extent, then, does Israel meet these criteria? To the usual charge that BDS singles Israel out for exceptional sanctions when many nations—including the United States—are guilty of some egregious injustice or aggression, an initial response is simply that the fact that many states infringe international law does not in any way exonerate Israel from its obligations to end an illegal occupation or to apply universal standards of human rights. Indeed, it is because Israel is constantly distinguished or singled out from other nations, particularly here in the United States, that a boycott, divestment, and sanctions campaign is justified. As is by now well known, Israel is the largest recipient of US foreign aid, receiving currently about $3 billion per year. US aid underwrites Israel’s commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including not only the use of weapons like white phosphorous against civilians, but also such offenses as collective punishment, systematic torture, and the extended occupation of Palestinian territory in violation of the Geneva Conventions. Indeed, Israel has violated more UN resolutions than any other state in the world, including twenty-eight Security Council resolutions that are legally binding on member states, largely because it has been consistently protected from any attempt to enforce those resolutions by the veto power the United States holds on the Security Council.

Nonetheless, public officials and academics who have critiqued Israel have faced campaigns of distortion, intimidation, threats of termination, and denial or loss of tenure. While Norman Finkelstein’s may be the best-known academic case, campaigns have also targeted scholars like Nadia Abu El Haj, Sami Al-Arian, David Shorter, and David Klein, in direct attempts to restrict their freedom of speech. Well-orchestrated efforts to define criticism of Israel as anti-Semitism or to intimidate Students for Justice in Palestine have resulted in the extraordinary prosecution of the Irvine 11, students who peacefully protested the visit of the Israeli ambassador, or California Senate Resolution, HR 35, which effectively defines peaceful protests against Israeli policies as hateful, and hence prohibited, and is clearly an attempt to model legislation for other states.

Israel is singled out most clearly by being the only country that cannot be criticized openly in the United States and on university campuses without serious repercussions.

This climate of orchestrated harassment of critics of Zionism, designed to intimidate and silence, bears no comparison with the no less orchestrated complaints by pro-Israel students on campuses that criticism of Israel is tantamount to anti-Semitism. To concede that point would be to undermine the very foundations of the university, which must allow any belief and any political system, political or religious, and however deeply held, to be subjected to reasonable criticism.

The censorship that US academics and citizens face regarding criticism of Israel is negligible, however, compared to the daily regime of occupation and siege that denies Palestinian scholarsthe right to free movement and prevents them from attending classes, taking exams, or studying abroad on fellowships; that subjects universities to frequent and arbitrary closures, constituting collective punishment; or that willfully destroys academic institutions, like the American International School or the Islamic University of Gaza in 2009, which were destroyed along with some twenty other schools and colleges. If there has been anywhere a systematic denial of academic freedom to a whole population, rather than to specific individuals or to institutions, it is surely in Palestine under Israeli occupation.3

Yet it is putatively on the grounds of academic freedom that the AAUP has rejected the academic boycott of Israel. Because the AAUP is a respected body whose opinions are taken seriously by academics worldwide, it is important to trace its position in relation to the boycott and explain why it is untenable. In 2005, responding to the UK Association of University Teachers’ call for a boycott of two Israeli universities, Haifa and Bar-Ilan (another resolution overturned this resolution a few months later), the AAUP condemned the boycott on the basis of academic freedom:

Since its founding in 1915, the AAUP has been committed to preserving and advancing the free exchange of ideas among academics irrespective of governmental policies and however unpalatable those policies may be viewed. We reject proposals that curtail the freedom of teachers and researchers to engage in work with academic colleagues, and we reaffirm the paramount importance of the freest possible international movement of scholars and ideas.

A year later, the AAUP published “On Academic Boycotts” to support its position that boycotts are “prima facie violations of academic freedom.” This condemnation of the academic boycott on the grounds of academic freedom has been thoroughly critiqued by scholars such as Marcy Newman, Lisa Taraki, Omar Barghouti, and Judith Butler, who contend that the AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom academic freedom extolled by the AAUP is a geopolitically based privilege rather than a transhistorical right. Butler has called for a “more robust conception of academic freedom, one that considers the material and institutional foreclosures that make it impossible for certain historical subjects to lay claim to the discourse of rights itself.” Notably, the AAUP allowed critics of its statement to voice their opinions in Academe, thus ironically appearing to many academics, who expressed outrage at these critics, to be condemnatory of Israel.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. The AAUP’s deliberations on the academic and cultural boycott of Israeli universities effectively promoted the idea of Israel as Agamben’s state of exception. Just as the state of Israel governs through an order “that allows for the physical elimination not only of political adversaries but of entire categories of citizens who for some reason cannot be integrated into the political system,”the AAUP has proceeded to eliminate the rights of Palestinians from its arguments.

The academic boycott statement referred to the 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure: “institutions of higher education are conducted for the common good . . . [which] depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition.” But if universities are conducted for a universal idea of the common good, the grounds for the academic boycott of Israeli universities seem fairly obvious. The common good of the Islamic University of Gaza cannot be served by bombing it; neither can a university function for the common good if it is established in a settlement area: witness Ariel College, a West Bank campus of Bar-Ilan University, now Ariel University Center of Samaria, fully accredited in July 2012. Established illegally under international law, on occupied Palestinian territory, it is open only to Jewish academics and students, a separate and unequal apartheid institution. The question undoubtedly becomes, for whose common good are universities established? Whose common good matters? How should the common good be defined in a country under occupation? Once we interrogate the particularity of the common good, it becomes clear that this notion operates under the aegis of a liberal humanism that ignores colonialism or racial oppression. While both early Zionists and contemporary leaders have been brazen about the settler colonial nature of Israel’s enterprise, all of the AAUP’s statements are noteworthy for the absence of any mention of Israeli colonialism or its repressive military. Let us reflect on this willful blindness: the words colonialism and occupation simply do not appear in the Association’s statements.

Next, the AAUP distinguished censure, “which brings public attention to an administration that has violated the organization’s principles and standards,” from a boycott. “Throughout its history,” the AAUP claimed, it had “approved numerous resolutions condemning regimes and institutions that limit the freedoms of citizens and faculty,” but only in the case of South Africa had it supported resolutions both of condemnation and of divestment. The AAUP not only censured South Africa but actively supported the divestment movement against apartheid.

Now it refuses even the censure of Israel. Inconsistent as this is, the contradictions have recently been compounded. The December 2008 bombing of the Islamic University of Gaza, an institution serving twenty thousand students and comprising ten faculties including education, religion, art, medicine, engineering, and nursing, drew no comment from the AAUP. Yet the AAUP in 2007 had continued its commitment to condemning institutions that limited the freedoms of students and faculty by censuring four New Orleans universities for closing departments in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina; and at its annual meeting in 2008, it condemned the government of Iran for discriminating against and denying educational opportunities to its Baha’i community.

In 2010, however, the AAUP, responding to allegations of anti-Semitism at UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, and Rutgers, issued a statement in support of free speech but also suggested that university administrators use a working definition of antiSemitism to monitor individual cases. Part of the working definition includes “denying to Jews the right of self-determination (such as by claiming that Zionism is racism).”

This definition, which confuses criticism of a state with hatred of an ethnoreligious group, itself participates in the larger climate of censorship that we remarked on above. But given that the AAUP accepts the idea that settler colonialism is self-determination and implicitly denies the freedom to criticize Israel to the US-based Palestinian students its policies so drastically affects, should we AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom 8

be surprised that the organization has refused to censure Israeli universities, crucial instruments in the extension and maintenance of Israel’s regime of dispossession and settlement?

Instead the AAUP has satisfied itself by condemning criticisms of individuals’ writings as part of protecting the speaking of truth. At the 2007 annual meeting of the AAUP, Joan E. Bertin, the plenary speaker, portrayed attacks on Norman Finkelstein, Stephen Walt, and John Mearsheimer as simply part of the taboos against speech about Israel and Palestine and presented these, in a tactic of normalization, as “‘mutually destructive reductionism’ that prevents recognition of alternate views.” The report of the speech stressed the need for competing perspectives to foster discussion, thus equating the politics of settler colonialism and Palestinian protest, and assuming that both sides are equally heard in the United States.

In the spirit of this condemnation of individual acts—as if they were aberrant from the US government’s support of the Israeli state and its institutions—the AAUP recognizes only the right of individual faculty not to cooperate with institutions while it opposes any systematic boycott that “threatens the principles of free expression and communication on which we collectively depend.”12 It is crucial to repeat that the academic and cultural boycott is against Israeli institutions, all of which are complicit in occupation and create conditions under which the freedoms imagined by the AAUP cannot exist. The boycott does not extend to individual Israeli speakers invited to speak in the United States or to individual scholars writing a paper together. The point of the boycott is structural and is meant to challenge the state of exception through which Israel has escaped reprimand or penalty and has created conditions under which the rights of Palestinian scholars, academics, and students are routinely suppressed. In this context, it becomes a luxury for North American academics to appeal to a distinctly one-sided and restrictive version of the principles of academic freedom while accepting complicity in the denial of those rights to not just individuals but whole populations.

We would do well to remember the words of Howard Zinn in a lecture in South Africa during apartheid: “To me, academic freedom has always meant the right to insist that freedom be more than academic—that the university, because of its special claim to be a place for the pursuit of truth, be a place where we can challenge not only ideas but the institutions, the practices of society, measuring them against millennia-old ideals of equality and justice.” If academic freedom is, indeed, a universal value, not one restricted to a few who are privileged by geography and colonial histories, then the Palestinian call for an academic and cultural boycott of Israel becomes, as South Africa was in the 1980s, a test case for our intellectual and moral consistency. If we or the AAUP refuse to endorse that call, then the commitment to academic freedom becomes vacuous and meaningless, an assertion of privilege and entitlement, not of fundamental values. Palestinian education, like Palestinian culture and civil society, has been systematically targeted for destruction: it is no longer a matter of the infringement of the free speech of a few individuals but a case in which, in the time-honored manner of settler colonialism, a powerful and well-armed state seeks to extinguish the cultural life and identity of an indigenous people. Not only is the boycott movement the only practical possibility for Palestinian survival, its application is principled and defined in its scope and ends. No clearer case has existed for the extension of an academic boycott since the ANC made its similar call for boycott and divestment in the struggle against South African apartheid. To continue to duck what is increasingly one of the defining moral and political struggles of our time would be not merely inconsistent but intellectually and ethically bankrupt. The oldest US organization representing academics and scholars can do better than that, and it is time for it to do so. We must cease to make an exception of Israel.

David Lloyd is Distinguished Professor of English at the University of California, Riverside. His most recent book is Irish Culture and Colonial Modernity (Cambridge, 2011). Malini Johar Schueller is Professor of English at the University of Florida. Her most recent book is Locating Race: Global Sites of Post-colonial Citizenship (2009).

Notes and links

Journal of Academic Freedom

American Association of University ProfessorsVolume 4

Table of Contents

All essays are in .pdf format.JAF invites responses to the essays it publishes. While we are interested in supporting dialogue in general, given the academic character of the journal, we particularly encourage submissions that engage in thoughtful and well-supported ways with the content and arguments of our published essays. Send your response to jaf@aaup.org.

Editor’s Introduction

By Ashley DawsonRethinking Academic Boycotts

By Marjorie HeinsPalestine, Boycott, and Academic Freedom: A Reassessment Introduction

By Bill V. MullenBoycott, Academic Freedom, and the Moral Responsibility to Uphold Human Rights

By Omar BarghoutiThe Israeli State of Exception and the Case for Academic Boycott

By David Lloyd and Malini Johar SchuellerBoycotts against Israel and the Question of Academic Freedom in American Universities in the Arab World

By Sami Hermez and Mayssoun SoukariehChanging My Mind about the Boycott

By Joan W. ScottAcademic Freedom Encompasses the Right to Boycott: Why the AAUP Should Support the Palestinian Call for the Academic Boycott of Israel

By Rima Najjar KapitanMarket Forces and the College Classroom: Losing Sovereignty

By Michael Stein, Christopher Scribner, and David BrownAcademic Freedom from Below: Toward an Adjunct-Centered Struggle

By Jan Clausen and Eva-Maria SwidlerBEYOND THE STALEMATE? THE ONGOING ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN IMPASSE

Mustafa Barghouti

2pm, Sunday, 13th October 2013

Birkbeck College, LondonIs there a way forward? At a time when it is hard to see the prospect of significant change in the Israeli-Palestinian situation and the end of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Independent Jewish Voices is delighted to welcome the distinguished Palestinian activist, politician and doctor, Mustafa Barghouthi.

Keynote address by Mustafa Barghouthi

To be preceded by a panel discussion on forms of intervention with

●Israeli human rights activist, Miri Weingarten

●Palestinian-British author of the acclaimed novel, Out of It, Selma Dabbagh

●UK-based journalist from Gaza, Jayyab Abusafia and

●initiator of the Gaza scholarship programme at Oxford University,Charlotte SeymourLynne Segal will open the event, Tony Klug and Jacqueline Rose will chair.

B34 Birkbeck, University of London,

Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX

Tickets £10 (£5 for students)

Space is limited so please book early to avoid disappointment.

For booking & further details contact Merav

atweb@ijv.org.uk or visitwww.ijv.org.uk