Israel no longer ignores East Jerusalem but it’s avoiding the hard questions

The separation wall in Abu Dis between East Jerusalem and the West Bank

Nir Hasson writes in Haaretz on 21 August 2023:

The five-year development plan for East Jerusalem, approved by the government on Sunday, is another step in the dramatic change in Israel’s treatment of Jerusalem’s Palestinian residents.

Since the Six Day War in 1967, it has been clear to Israelis and Palestinians that Jerusalem is united only in festive slogans. Except on Jerusalem Day, it remains divided throughout the year. East Jerusalem operates like a separate city, almost as though there had never been an annexation – with a completely separate public transportation, power grid, school curriculum and business center.

The Israeli authorities hardly showed any interest in what was happening in the Palestinian neighborhoods, and didn’t see themselves as obligated to provide them with services. More crucially, the Jewish and Palestinian residents of Jerusalem didn’t view themselves as sharing the same city.

The Palestinians youths studied the Jordanian curriculum, and later that of the Palestinian Authority. They enrolled in West Bank universities, married men and women from Hebron, and made their living in the PA, with very few working for Jews in the city. They lived parallel to those on the west side of the city, like lines that never cross.

This separation stemmed from a shared perception of “permanent temporariness.” Israelis recite slogans about the city’s eternal unity, but didn’t truly believe in it. Therefore, they saw no need to invest in the east side of the city. The Palestinians couldn’t imagine that the occupation would continue. As a result, they saw no need to connect with Israeli society, learn Hebrew, or enroll in the Hebrew University on Mt. Scopus.

The change began with the establishment of the separation wall about twenty years ago, which cut East Jerusalem off from the West Bank. In addition to the physical wall, a legal obstacle was established. An amendment to the citizenship law prevented the reunification of families separated by the wall.

As a result, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living in East Jerusalem were pushed towards Israeli society. Students and parents showed interest in studying under Israel’s high school curriculum and enrolling in Hebrew-speaking colleges. The workplaces filled with talented and ambitious Palestinian youths. The two worlds began to intersect.

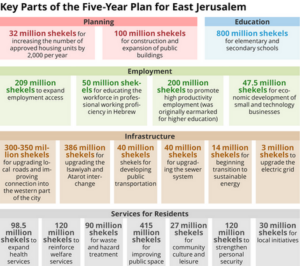

Key provisions in the five-year plan for East Jerusalem

The collapse of the peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in 2014 was a turning point. From that moment, even the most optimistic Palestinians have had difficulty imagining a future in which al-Quds (Jerusalem in Arabic), is the capital of an independent Palestine. Three months after peace talks ended, a sort of mini-intifada swept the city in response to the murder of Mohammed Abu Khdeir, an East Jerusalem resident. In hindsight, the protests were a sort of declaration of independence for East Jerusalem as a new political community, semi-detached from that of the West Bank.

The violence hastened Israeli government officials to reconsider the eastern side of the city. Even the most cynical Israelis realized that East Jerusalem – a city the size of Tel Aviv – is here to stay.

The Shin Bet security services realized that a city can’t be run by force. Elad, a right-wing organization that champions East Jerusalem settlements were glad to reinforce Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem. And Finance Ministry realized that the future of Jerusalem’s economy depends on Palestinians.

This led to the approval of the first five-year development plan in 2018. During the time of Mayor Nir Barkat and Jerusalem Affairs Minister Ze’ev Elkin, 2.1 billion shekels were allocated for the development of East Jerusalem. The influx of funds changed how government authorities treated East Jerusalem – no longer as a neglected backyard but as a place deserving attention and care.

The plan expedited the Israelization of the education system and encouraged thousands of Palestinians to enroll in Israeli educational institutions. It also led to vocational training for workers, developed infrastructure, and overall improved living conditions in Palestinian neighborhoods.

At the same time, there were clear efforts to evade some of the most challenging and sensitive issues in the Israeli-Palestinian relationship in Jerusalem. This includes housing shortages, permit restrictions, police violence, and the predicament of the neighborhoods beyond the barrier, where over a hundred thousand people reside in substandard conditions. Above all, the plan did not touch upon the crucial question of why so many of the city’s residents do not hold Israeli citizenship and how the state envisions their future.

Reality Alongside Conflict

The first five-year development plan will conclude in December. The Jerusalem Affairs Ministry prepared the new plan, approved on Sunday, over the course of this year. It was supposed to pass on Jerusalem Day in May. However, at the last moment, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich decided to block it. Despite opposition from the municipality to the Shin Bet security agency, Smotrich argued that the clause promoting higher education contradicted Israeli interests.

Over the past two months, most of the entities involved in the plan tried unsuccessfully to convince Smotrich to reverse his stance. Ultimately, the plan was approved without the clause promoting higher education. It was replaced with a vague clause about “high productivity employment.” Officials believe they will still be able to continue operating pre-academic training programs that encourage higher education for Palestinians.

The other sections remain largely untouched and some were even expanded. The most noteworthy is the goal to approve 2,000 new housing units for Arab residents of Jerusalem each year. The plan does not elaborate on how this will be achieved. Presumably, the city’s planning authorities will struggle significantly to meet their target.

Police officers in the old city in East Jerusalem in 2022

In addition, the plan generously funds several areas for the next five years, with 800 million shekels for education, 350 million for infrastructure, 40 million for public transportation, 100 million for public buildings, and 120 million for welfare.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, government ministers, and Jerusalem Mayor Moshe Leon sought to frame the approval as a triumph for sovereignty and unity. In addition, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir included a large budget for additional police officers and police stations in East Jerusalem.

As in the previous plan, land registration clauses could particularly assist settler organizations. The health section still doesn’t require health funds to stop the ongoing practice of outsourcing medical services to subcontractors. In addition, the education section emphasizes Israeli identity in the curriculum over actually improving the education provided. But in the end, the new plan is an important and positive development for all Jerusalem residents.

These five-year plans join with grassroots efforts to reshape Jerusalem. Israelis and Palestinians encounter each other today in the city on equal footing – at universities, workplaces, shopping centers, and on the light rail. In spite of right-wing hopes, the process doesn’t alienate the residents from their brethren in Gaza and the West Bank or weaken their Palestinian identity.

Like the Arabs living within the 1948 borders, reality and conflict coexist. The more Israeli an Arab Israeli citizen or resident is in their daily life, the more they identify as Palestinian. This explains why the plans cannot truly solve any substantial problems. As long as Israelis don’t genuinely grapple with the tough question about Jerusalem’s future, the plan cannot seriously address the disparities in East Jerusalem.

The plan’s approval on Sunday by the government makes the city slightly more equitable and much more complex. Jerusalem no longer lends itself to simplistic solutions of redistribution.

However, these processes also emphasize the absurdity at the foundation of the united city: a capital city where only 60% of its residents have the right to vote for the parliament that meets in it.

The new plan slightly undermines the temporary structure established in 1967, and it brings us closer to addressing the truly significant question: Does Israel envision its capital as a truly equal city, the capital of two peoples, or as a city where one half must continue to invest more and more resources to oppress the other?

This article is reproduced in its entirety