Israel has already been convicted of genocide, at least at this people’s court

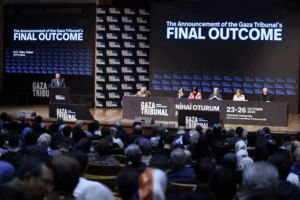

Reading of the Gaza Tribunal’s verdict, Istanbul University, 26 October 2025

Yair Foldes reports in Haaretz on 4 November 2025:

For almost 20 minutes, in front of hundreds of people filling the large hall at Istanbul University, Prof. Christine Chinkin, an expert on international law and Jury Chair of the “Gaza Tribunal,” read a list of war crimes and crimes against humanity that the jury had decided Israel was guilty of:

Starvation and famine, domicide (deliberate destruction of civilian building infrastructures), ecocide (destruction of the environment), deliberate destruction and targeting of the healthcare system, reprocide (“intentional and systematic targeting of reproductive care”), scholasticide (“the genocide of knowledge and of Palestine’s intellectual future”), and other injustices.

When she finished speaking, the audience – many of them students and political activists from across Turkey, wearing keffiyehs or Palestinian flag pins – applauded for a long time. They did not conceal their joy at the foregone conclusion reached by the tribunal, held over four days last month, after long days of discussions and testimony.

Istanbul University is located atop the city’s historic quarter, and it has served students for nearly 600 years. About two weeks ago, amid classes in the exact sciences, law, and the humanities, the third and final session of the Gaza Tribunal opened in one of its spacious halls.

This final session, which lasted four days, followed earlier meetings held in London in November 2024 and in Sarajevo in May. The international initiative included academics, jurists, intellectuals and political activists who, over the past year, collected information, expert opinions, and testimonies from Gazan civilians to assemble a broad picture of Israel’s activity in the Strip since the start of the war.

Without any legal authority or enforcement powers, the tribunal does not seek to determine guilt or issue binding verdicts. Its purpose, the organizers explain, is “to close the enforcement gap” regarding Israel by applying civil society pressure on governments around the world.

According to the organizers, the tribunal’s activities are funded with the assistance of the Islamic Cooperation Youth Forum (ICYF), which operates under the Organization of Islamic Cooperation – a body comprising 57 member states. However, they emphasize that the funding organization has no influence over the tribunal’s decision-making or mechanisms and is not obliged to show solidarity with it.

“This is a political tribunal”

The gathering in Istanbul continues a growing tradition of “people’s tribunals” established in conflict zones around the world. These include the Russell Tribunal, founded by British philosopher Bertrand Russell in 1966 to examine U.S. actions in the Vietnam War; the Third Russell Tribunal, convened in 1973 to address human rights violations in Argentina and Brazil; and the “China Tribunal,” held in London in 2018, which investigated China’s organ-harvesting policies.

At the opening session of the first Russell Tribunal, then also known as “The International War Crimes Committee,” philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre said: “It is true that our Tribunal is not an institution. But, it is not a substitute for any institution already in existence: it is, on the contrary, formed out of a void and for a real need.”

A similar rationale seems to underlie the establishment of the current tribunal. “The situation in Gaza is a dramatic example in which the established order failed to stop genocide,” Prof. Richard Falk, Chairman of the tribunal in Istanbul, told Haaretz. “It’s very hard to measure the effect. I think it does influence the media’s consciousness and produces an archive of testimonies.”

Falk gave as an example another tribunal he participated in, in 2005, concerning the Second Iraq War. “It had an effect on the public discourse about the war, particularly in the region, and to some extent influenced the description or analysis of the war. It led to some books and contributed to an understanding of liberal intellectual thought,” he says.

Falk, who taught international law for decades at Princeton University and served as UN Special Rapporteur in the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the previous decade, has often faced criticism for his views and activities. And, despite his Jewish background, some have accused him of antisemitism.

Now 94 years old, Falk moves slowly but remains sharp-tongued, especially in his criticism of Israel and Zionism. “Until Zionist ideology is rejected by the Israeli state, Israel will not recover its legitimacy as a sovereign member of the international community,” he said. “Israel has dominated the battlefield, but it has lost what I call the legitimacy war, and the Palestinians have gradually come to control the public discourse about it.”

Falk’s views are typical among tribunal participants, who make no attempt to conceal their political views. “In the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, everything is political,” British-Israeli historian Avi Shlaim, who participated in the final session, told Haaretz. “I can’t imagine how a people’s tribunal could be ethically neutral or objective. Here, there is no pretense of objectivity – this is a political tribunal. It’s like the Russell Tribunal; similarly, the purpose here is to mobilize public opinion worldwide against the war and destruction in Gaza.”

The tribunal also refrained from inviting Israeli representatives to defend the army’s actions in Gaza. In response to Haaretz’s question, members said they initially considered inviting the Israeli government and other parties with vested interests to present their views before the jury. But “given the clear and consistent pattern of denial, obstruction, and non-cooperation in previous international inquiries” demonstrated by Israel, they assumed that such an invitation would not receive a serious response.

At the same time, they reiterated that the tribunal’s purpose is not “legal-political” but “moral and symbolic.”

Shlaim agrees. In his view, Israel’s participation would be unacceptable. “Israelis, if they feel the world is against them, need to understand and take responsibility for the impunity granted Israel by its key allies and the deliberate and ongoing attempts to silence and criminalize those who protest the genocide in Gaza…” he said. “The purpose of the tribunal is to show solidarity with the victims, not give a platform to the propaganda of war criminals.”

The tribunal’s organizers initially declined to answer Haaretz’s question regarding their position on Hamas’ actions in the war, and in particular, whether it views the abduction of civilians on October 7 as war crimes.

After a follow-up inquiry, they replied that they “hold differing views and approaches regarding this issue; therefore, it would not be accurate to state that the Tribunal has a common position. Consequently, we chose not to respond to this question, as offering an answer that adequately represents all members would be challenging.”

Most of the discussions focused on events in the Strip since the start of the war. Dozens of testimonies from Gazans were presented, most of them recorded in previous months, others delivered live from Gaza or by refugees who had fled the region. The tribunal’s staff emphasized that the testimonies were “reviewed by expert academics and practitioners specializing in relevant fields, particularly in law and human rights.”

Haidar Eid, a lecturer on literature and cultural studies at Al-Aqsa University in Gaza, testified from his home in South Africa, where he relocated two months after the war began: “Personally, I have lost 54 relatives… 39 colleagues from Al-Aqsa University… and more than 280 students, including some of my best literature students…”

Abubaker Abed, a 22-year-old Gazan journalist, shared a similar story. “I lost more than 50 family members, including my cousin’s entire family, who were wiped out in the last week of March… and a year before this, my aunt’s family was also wiped out…” he said.

He also described his work as a journalist during the war: “Documenting genocide is not just like what you’d expect. It’s about believing that… your next report might be your last… We’ve never had time to mourn our dead. Once, while I was reporting, my cousin and his son were killed on my street… I had to go live on air on TV and say, ‘Well, my cousin was killed and his son was killed…'”

Ahmed Alnaouq, a Palestinian journalist now living in the United Kingdom, told the tribunal that on one night in October 2023, 21 members of his family were killed in a bombing in Deir al-Balah. Among them, he said, were his 14 nieces and nephews, all younger than 13.

“My family home was in Deir al-Balah, in what Israel calls the humanitarian zone, a safe zone,” he testified. “They did not pose any danger to Israel, they did not fire missiles. They did not attack any Israeli. And yet, they were killed.” Alnaouq added that his relatives tried to locate his family members, but because of the condition of the bodies, they were unable to identify them.

“…What enabled this genocide, this apartheid and the occupation of Israeli land is not only the Israeli government, but also the governments worldwide who aided and abetted… and the Western media, which gave Israel the cover and the atmosphere to bomb and to kill as many Palestinians as it desired,” he said.

It is not the first time Alnaouq’s name has appeared in Haaretz. In 2022, he was interviewed for a story about an exhibition by Gazan artist Zainab al-Qolaq, who lost 22 members of her family a year earlier in an IDF attack during the fighting with Gaza in May 2021. Alnaouq was then one of those responsible for mounting the exhibition in Gaza. Less than a year and a half later, he suffered a similar tragedy.

Several testimonies addressed domicide, a term coined during the Gaza war to describe “the intentional mass destruction of residential properties and their infrastructure,” according to the tribunal.

Gazan journalist Mohamed Al Helou, now living in Europe, spoke at length about life in the Strip before the war. “My favorite restaurant was Al-Mamlouk on Al-Baz Street. I used to eat there every day – falafel, hummus, ful,” he said. “The owner and his entire family [were] killed by Israel. The restaurant is gone. The people are gone.” He described a community where “we never locked our doors. Our lives were shared.”

Al Helou’s home in the Shujaiyeh neighborhood was destroyed during an Israeli attack in November 2023. “Fourteen people lived in our house – all my brothers and sisters, my uncle’s family, my brother’s family, my grandmother Suad, who is 85 years old. A house full of love and life. In Palestine, a home is never four walls – it’s where generations live together, where neighbors are families, where every corner holds a story for Palestinians.”

He said his family managed to flee to the southern Strip before the attack. But since then, he said, his nephew has died of starvation, and his brother and cousin were shot to death by Israeli snipers while searching for food.

“Genocide must be named”

Toward the weekend, after three days of discussions, the tribunal jury convened to deliver what it called its final verdict: “It is a civil society response to the continuing lack of accountability for the commission by Israel of genocide in the Gaza Strip. We believe that genocide must be named and documented and that impunity feeds continuing violence throughout the globe. Genocide in Gaza is the concern of all humanity. When states are silent, civil society can and must speak out,” said jury chair Chinkin.

It now remains to be seen whether, and how, the gathering will influence public opinion worldwide. In the coming days, the tribunal promises to release a comprehensive document summarizing its findings.

According to the organizers, with the publication of this document, “the tribunal will fulfill its historical mandate and serve as a moral testimony and a legal reference for future generations.”

This article is reproduced in its entirety