‘I would like for Israelis to understand that Zionism is racism’ – director of film ‘Lyd’

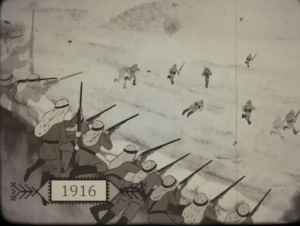

A scene from the alternative reality in the film ‘Lyd’

Nirit Anderman writes in Haaretz on 23 November 2024:

Any dictatorship worthy of the name would be proud of the way things unfolded in Israel on October 10 this year. Immediately after a right-wing activist learned that the Palestinian film “Lyd” – the Arabic name for the city of Lod – was going to be screened at the Al Saraya Theater in Jaffa, and fired off an urgent message to, among others, Culture and Sports Minister Miki Zohar, claiming that it endangered Israel’s security – the minister sprung into action.

Zohar declared that the film presents a “delusional, mendacious picture” and asked the Israel Police to prevent the screening. Officers hurried to obey, summoned the theater’s director for a “warning talk” and banned the event – because “no request for a permit to show the film had been submitted” to the country’s Film Review Board. The icing on the cake came from National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, who wrote on X (formerly Twitter): “I hear the howls of people on the left over the cancellation of the screening of the film ‘Lyd’ in a Jaffa theater. They need to understand that a law is a law and an order is an order.”

The screening of “Lyd,” which focuses on Israel’s conquest of the once-thriving Arab city during the War of Independence, was canceled; the clear and present danger to Israel’s existence was averted. One can only imagine what would have happened on October 7 last year if the authorities had mobilized for action with the same kind of efficiency and speed. In any event, 14 organizations representing creative artists, shocked by the intolerable ease with which the event was banned, urged Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara to clarify to the culture minister of culture and the police that it is not their job to interpret cultural content or to prevent its presentation in public. “The task of the Israel Police is to protect the freedom of expression, not to protect those who seek to harm and nullify it,” the groups declared.

By then, Rami Younis, the film’s co-director, had already boarded a flight for the United States, where he began a round of international screenings of “Lyd.” Since then he’s been shuttling between cities in the United States, speaking with audiences and describing how the Israel Police, in effect, suddenly became censors, and relating how he himself generally has become a scapegoat who’s regularly persecuted by right-wing exponents in Israel.

A Palestinian resident and citizen of Israel, who is adamant about expressing his opinions even if he knows they will upset many Jews in his midst, Younis is accustomed to being attacked and knows what it feels like to be silenced. Google his name in Hebrew, and one of the top results is “Meet the denigrator – BDS,” a link that leads to a page devoted to him on a right-wing site that brands people “denigrators of Israel.”

Rami Younis.

It’s precisely because Younis is so accustomed to such sharp criticism that he waited over a year before deciding, together with his Jewish-American co-director, Sarah Ema Friedland, to arrange to show “Lyd” in Israel. The movie’s world premiere was in August 2023 at the Amman International Film Festival, where it won two prizes, and just when it was supposed to be released in Israel and worldwide, October 7 ruined all the plans.

“At the beginning of the war, it was literally like taking your life in your hands to screen a film like that in Israel, so we censored ourselves simply out of fear of our personal safety,” Younis says in a video interview conducted earlier this month from a hotel room in Massachusetts. “After all, we’re living in a country where Ben-Gvir is the minister of internal security, so we just waited and waited until it was impossible to wait any longer.

“After all,” he continues, “the ongoing nightmare isn’t ending, so what will we do – not screen the film? So, when Al Saraya Theater told us, ‘We want to screen it,’ we agreed. Before that we actually done one showing in Lod, under the radar, without publicizing it. We are aware of where we live and of the atmosphere of McCarthyism and fascism surrounding us.”

Younis had already seen how the police prohibited the screening in August, in both Haifa and Jaffa, of the new film by Mohammad Bakri, “Jenin Jenin 2,” out of fear that it would “disturb the public order”; the police also shut down the Haifa branch of the Arab-Jewish Hadash party. What did surprise Younis, however, was the culture minister’s decision to join right-wing zealots in the anti-Palestinian frenzy over his film.

“It’s a disgrace for the inflammatory, mendacious film ‘Lyd,’ which was written and produced by activists supporting the boycott against Israel, to be screened in the territory of the state,” Zohar wrote that day. “The film, which presents a delusional, false picture, according to which Israel Defense Forces soldiers supposedly perpetrated a brutal massacre, describes the expulsion of the Palestinians from Lod and presents a lying picture that the city of Lod was supposedly destroyed because of the State of Israel, continues to slander Israel and the soldiers of the IDF.”

A few days later, in an interview with Channel 13 News, the minister added that “Lyd” is “a film that is truly inferior, a groundless lie, [characterized by] inventions with no relation to reality, against the Jewish people, against the nation of Israel, against the State of Israel.”

This month another film about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict suffered similar treatment. The Culture Ministry’s Film Review Board warned the country’s cinematheques not to screen Neta Shoshani’s “1948 – Remember, Remember Not,” and thus further reviving the use of a British Mandate-era ordinance requiring a screening permit as a vehicle for enabling the censorship of controversial films.

As often happens with Younis, the orchestrated offensive launched against his film produced the opposite results. “What a great PR gift they give me,” he says, with a smile. “I want to exploit this platform to thank those who did it.”

Sarcasm aside, Younis is correct. Without the robust attack by Minister Zohar, and the ban the police imposed on the small Jaffa theater, it’s likely that many would have never become aware of the film. But the prohibition on the screening, issued impulsively – without any of the self-styled censors having bothered to watch the movie – thrust it into headlines overnight, both in Israel and abroad, where its screenings have been playing before full houses. Because who wouldn’t want to see such a dangerous film, a ticking cinematic bomb, a creation that succeeded in stressing out an Israeli minister to the point where he took such rash action?

An Israeli soldier in Lod, 1948.

Younis: “I had a premonition about what was going to happen, but I didn’t know Miki Zohar would copy-paste the message of that right-wing activist. He gave me a tremendous publicity gift. But the fact that the police obey a minister who simply doesn’t like something and decides to cancel it – that’s insane. The result is that many in the international community now realize what we are going through, seeing where we live, and understanding that people are afraid of this film. And why? Only because it dares to imagine a situation in which everyone is equal and free.”

As result of the ban, many in the international community now realize what we are going through, seeing where we live, and understanding that people are afraid of this film. And why? Only because it dares to imagine a situation in which everyone is equal and free.

“Lyd” is a hybrid work, intertwining documentary and fantasy. It tells the story of the city of Lod, in central Israel, by means of a combination of archival footage and interviews both historical and new, along with animation that creates an alternative sort of reality. The documentary part focuses on bustling pre-1948 Lod, and about the mortal blow it suffered in the Nakba – that is, during the 1947-49 Israeli War of Independence when more than 700,000 Arabs in the country fled or were expelled from their homes. The massacre soldiers in the nascent army allegedly perpetrated on Lod’s residents, the mass expulsion, looting and seizure of homes left behind –”Lyd” addresses all these painful subjects.

Indeed, by focusing on this one city, the film in effect tells the very real story of the Nakba of the entire Palestinian people. But Younis and Friedland also wrap the calamities that befell Lod in a cloak of fantasy. The city is anthropomorphized, transformed into a full-fledged character and allowed to use its own, first-person voice to paint an ultimately optimistic picture. That is, while playing a “What if?” game, the film’s creators have taken the liberty of imagining how the city of over 85,000 residents today would look today if the Nakba hadn’t happened. With the aid of animation, they recreate a flourishing and thriving place that the Jewish people did not destroy in order to establish its state.

In this film, you are in effect erasing Israel, making it disappear.

“We’ve created a reality in which there is no Zionism, no State of Israel, but our parallel universe dates back not to 1948 but to 1918. We annulled the Sykes-Picot agreement [of 1916], which divided the Middle East into British and French colonies. What I’m trying to say – and as an Arab I am allowed to say this – is that in this parallel universe the Arabs had a backbone and they rose up and ousted the Europeans. So, we created a situation in which Palestine exists as a state, but has Jews among its population as well, and everyone lives happily as equals between the river and the sea.”

Is that the situation you would like to see here?

“What I would like is for Israelis to understand that Zionism is racism, for them to understand that it’s out of the question not to acknowledge the crimes of the past. Because, as Tamer Nafar wrote in Haaretz not long ago, if you don’t acknowledge a crime, it repeats itself. And that is exactly why, at the beginning of the current war, we saw figures like [former Shin Bet security service head and current Agriculture Minister] Avi Dichter threatening a ‘second Nakba.’

“That’s really stupid because, after all, he doesn’t even recognize the first one. But it also shows that it worked for them in the past, because the world went along with it, and the fact is that to this day, apart from the Arab world and a few bleeding-heart left-wingers – no one actually acknowledges what happened to us. And if that’s so, then hey, it’s possible to do it again. That’s what I want people to understand.”

Studio brawl

Younis, 39, was born and raised in Lod. At a young age he became an activist, battling on behalf of the city’s beleaguered Palestinian population. His day job was working at a pharmaceuticals company (he has an undergraduate degree in biology), and afterward he and his friends demonstrated against home demolitions, among other things, and organized various cultural activities including film screenings.

At age 28, he changed course and joined the core group that founded Local Call, an activist-journalistic site committed to democracy, equality and resistance to the occupation. He began to work as a writer and editor, and also contributed to the site’s English-language twin, “972+.”

In 2015, he leaped into the political arena when he became media adviser to MK Hanin Zoabi (Balad), at the time probably the right wing’s most hated Arab lawmaker. “That was quite the challenge. I wanted to try my hand at it, it interested me, but the work in the Knesset was… I remember I would get there, park and go upstairs: I felt like one leg would go up while the other pulled in the opposite direction. I didn’t want to be there, it was really hard for me to go to work and see [ultranationalist MK Bezalel] Smotrich around me. The work itself was super-interesting and challenging – and also funny at times; it felt like one long episode of ‘Veep.’ But we didn’t succeed in getting a single law passed. So what were we doing sitting there, just issuing statements to the media?”

After a mere three months he’d had enough, and went back to journalism. And being a cultural entrepreneur at heart, he and a few friends from Lod also joined forces to create Palestine Music Expo, a Palestinian music festival that was held in Ramallah, in the West Bank, for three years starting in 2017, which received widespread coverage in leading international media outlets and attracted many guests from abroad, until it was wiped out by the pandemic three years later. “The idea was to forge a connection between the local music scene on both sides of the [separation] barrier, meaning Palestinian Israeli musicians from 1967, and musicians like me, 1948 people [exiles], and to connect them to the rest of the world,” he explains.

It was in this period that he met the American director Sara Ema Friedland, who suggested that he join her in a film project focusing on the history of Lod. They started to work, with the aid of a crowdfunding campaign. Then an unexpected email arrived. Roger Waters – the former front man of Pink Floyd, who is today a very vocal political activist who supports the boycott, divest and sanctions against Israel – said he wanted to support the movie.

Younis: “He knew me from my journalistic work in English and from the Palestine Music Expo. When he heard about our campaign, he simply contacted me and said, ‘I love the project, I want to support it.’ Do you know what it’s like to get up in the morning and see the name ‘Roger Waters’ in your inbox, and realize that he wants to back your film? It was an amazing moment.”

But as a journalist who knows that mentioning Waters’ name in an interview like this might sharply raise some eyebrows, Younis quickly adds notes that a large number of Palestinian philanthropists, and also Jews, contributed to the making of “Lyd” – just one of a number of activist efforts he has become involved in recent years.

“That’s what I do: cultural activism as a means to cope with systematic violence. It’s part of me and always will be,” Younis asserts. “Take music, for example – the Palestinians who are Israeli citizens have no live-music scene. We’re not played on Army Radio or on Army Radio’s all-music station. I don’t know whether Palestinian musicians even want to get airtime on Army Radio, but it’s still a problem.

“After all, it’s not like we can perform at the Barby club [in Tel Aviv] whenever we feel like it. Because of the occupation, because we’re Arabs in Israel, we don’t have the possibilities the Jewish public has. That’s a type of built-in violence, and the Palestine Music Expo was meant to challenge that. We said, ‘Okay, you’re preventing us from reaching the world? So we’ll bring the world to us.’ And it worked.”

As a result of his activities, he received an invitation in 2019 from Harvard University to take part in a program in which activists from different places and different fields met to brainstorm about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and ways to deal with it.

He spent an entire year there, and was planning to stay on and not return to Israel at all, but COVID put paid to that idea, too. He returned home, moved to Haifa and sank into depression. Until local political developments thrust him back into a serious activist mode of existence.

The disturbances of May 2021 – the clashes between Arabs and Jews in cities and towns throughout Israel, of which those in Lod were among the most violent, in the wake of Operation Guardian of the Walls in the Gaza Strip – led the Israeli media to seek out for articulate Israeli Palestinians. Younis, who speaks a rich Hebrew, is well-spoken and isn’t ashamed to present his views, seemed to be the perfect interviewee.

He was invited to Dov Gil-Har’s current events program on Channel 11, of the Kan Public Broadcasting Corporation. As he was waiting outside the studio, he relates, someone texted him that a few minutes earlier on the show, Gil-Har had asked a high-ranking police officer whether because of the violence in Lod, for example, the time hadn’t come “both to change the hard disc and the ammunition” as a means of defense against the Arab rioters.

Younis entered the studio in a rage. In a six-minute interview he lashed out at Gil-Har, accusing him of inciting violence against Arabs and calling for them to be shot at, and castigating the Israeli media for its partial and biased coverage of the unrest, and specifically of not delving into the history of the outbreak of violence in Lod. The two engaged in a verbal slugfest on live TV, Younis shouting at the host, “I will not be the Arab ‘pet’ you kick around.”

“I was totally worked up when I went into the studio,” Younis recalls. “How does a person who presents a program on the public broadcaster say things like that? I fought him. He talked to me about Kristallnacht [Gil-Har noted that Lod’s Jewish residents had compared the violence against them to the mass pogrom in Germany in 1938], but what did that have to do with it? You’re a nuclear power and you’re talking to me about Kristallnacht? That’s delusional! But already during the interview I saw myself translating it into English and disseminating it across the world – and I was right. One thing I learned at Harvard is that if we disseminate whatever happens to us as Palestinians in Israel to the world, if we communicate it to the world in a language that’s understood – then the world listens.”

Among those who listened closer to home were the producers of another Kan 11 show “On the Other Hand,” hosted by Guy Zohar, who invited the passionate Palestinian journalist to appear as a guest a few times. Later, when the broadcaster decided to produce a version of “On the Other Hand” for its Arabic-language channel, Kan 33, Younis was invited to serve as host of the pilot season. Premiering in November 2021, it was a daily current events show, critical and barbed exactly like Zohar’s, which sought to expose fake news in a bemused, cynical style.

Indeed, it was an unprecedented event for Channel 33. After years in which it was perceived as feeble, speaking Arabic but serving up a Zionist narrative, the new program constituted a refreshing and brazen break for it. It was a pioneering effort that dared to speak in a new language but also wasn’t afraid to be critical of Arab politics and society.

But that perspective set off alarm bells among the country’s ultra-nationalists. A right-wing activist who heard about Younis’ new gig dug up two old posts from social media: In one of them the activist-journalist had called IDF soldiers “Nazis,” and in the other he expressed support for BDS. The pursuit of Younis was on.

A furor erupted in the media, the ethics committee of the broadcasting corporation asked its CEO, Eldad Koblenz, to reconsider its airing of Younis’ show (Koblenz refused), and hard-right MKs decided that the subject justified what turned out to be a virulent session in the Knesset. (“It is inconceivable that a vile antisemite, a Jew hater, a contemptible inciter, should receive his salary from the Israeli taxpayer,” declared Likud MK Amichai Chickli, who is today minister of Diaspora affairs).

Younis, for his part, said nothing. “At Guy’s [Zohar’s] advice, I kept silent. I told myself: I’m not talking, I’m not giving interviews, let them do what they want, I will let the program do the talking. I remember telling Guy that the whole business reminds me a little of a Monty Python skit: We do the show and the crazies are outside with the pitchforks.”

Jews, not only Israelis, grow up with disinformation and all kinds of historical distortions, to the effect that not only was there no massacre, but that in 1948 the Arabs left of their own volition. But I don’t know a lot of people who just think, ‘Ahh, yallah, I’ll leave my home voluntarily.

The show, which was broadcast daily at 8 P.M., developed a life of its own on social media. Attacks on it from the right kept sparking headlines, and in short order the show’s popularity soared among Israel’s Arab population and even abroad.

“I wanted to be a lot more radical,” Younis says. “Guy Zohar pulled toward his direction, my editor pulled in his direction, but it didn’t matter – in the end we met in the middle, and the program was fantastic. Within half a year we passed the Hebrew-language show in terms of the number of viewers. To the credit of the corporation, they were courageous – we were the first program that was critical of the establishment in Arabic.”

“On the other hand,” he adds, “people on the Palestinian side didn’t understand why someone like me was there. ‘How can you appear on a channel like that?’ they asked. But I believe in disruption, in changing the rules of the game, in doing new and challenging things.”

The right-wing campaign against you was based on your social media posts, like the ones comparing soldiers to “Nazis” and supporting BDS. Do you still stand behind those notions?

“You know, I get the fact that journalists sometimes have to ask questions that may not reflect what they actually think, but how do you feel now, echoing what’s said about me on the right? Anyway, I’ll tell you why they’re doing it. The moment they’re confronted by an Arab with a backbone, who’s not afraid, who’s proud of his identity, who was at Harvard – and never held a weapon or called for violence – he’s slandered like crazy.

“The only reason I don’t take legal action against them,” Younis continues, “is that I don’t want to wallow in the mud with those people. So you’re now sitting opposite a person who had a successful television program, who made a successful film, who established a successful music festival, who was a Harvard fellow and was part of the founding collective of Local Call – and you’re asking him about an old post he wrote on Facebook?”

Since those comments ignited a kind of firestorm around you, they too are relevant.

“So I want to ask you a different question. Why am I being persecuted thanks to a post from seven years ago – which, by the way, was about a female [Palestinian] paramedic and nine civilians who were all shot in the upper body – in order to push me out of the industry? But [Jewish] Israeli journalists who wrote pieces praising the genocide after the war broke out in Gaza – why is no one doing anything in their case? Here I am, sitting with you for an interview about our successful film, which has now been banned in Israel, and we’re talking about a smear campaign against me by a right-wing activist. I have to say that from that standpoint, I don’t agree with you: There is a difference between reporting and echoing.”

You mentioned earlier that you were amused by the similarity between what happened with your show and a Monty Python skit. Was there a stage when it stopped amusing you?

“In 2022 it had already gone too far. The program’s first season had ended, and that November I was invited to moderate a panel discussion about Palestinian culture, and again a maelstrom erupted around me. An MK and some Kahanists demonstrated outside the Tikotin Museum in Haifa, where the event was held, and I was given police protection after one of the demonstrators said that the rules of engagement should be changed so a bullet could be fired between our [the panelists’] eyes. Things started to get scary.

“At the same time, my agent was negotiating with the corporation about my contract for the second season of the program, but despite the successful first season, which had millions of views, there was no progress. It was incredible. I could sense which way the wind was blowing. The new government was already in power, and I understood that what was going to happen was that [Communications Minister Shlomo] Karhi and all those lobotomized people who call themselves cabinet ministers were going to make me the poster boy of their battle against the public broadcaster. And with Ben-Gvir as minister of police, things were becoming dangerous and frightening. The people at Kan offered me something that didn’t make sense economically, so I just didn’t renew the contract.”

If the show was such a hit, how come your contract wasn’t renewed?

“That’s what’s frustrating about this story. Officially it was because of money, but let’s say that the gaps weren’t all that big. So if you have a presenter who attracts tens of millions of views, the show is built around him and his name, all the Palestinians in Israel watch it along with Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza and the Arab world – the fact that they didn’t bend over backward to keep me says something about where we’re living.

“In my situation, you can be the most suitable person for the job, you can be the best at what you do, and they won’t let you continue. I don’t want to sound like a crybaby or someone who victimizes himself, but that’s what’s like being an Arab in this country. It definitely reeks of McCarthyism.”

Content and form

The idea for “Lyd” came to Sarah Ema Friedland after she read an excerpt from the book “My Promised Land,” by journalist Ari Shavit, in The New Yorker, where she learned for the first time about how the Nakba played out in Lod. It was clear from the outset that she would need a Palestinian partner for her project. A friend introduced her to Younis and they hit it off instantly.

At first they had in mind a standard documentary, but their approach shifted over time. “In the end we decided that in our film not only the content would defy the hegemonic history, but so would the form,” Friedland says, in a video conversation from the U.S. “So we decided to use the city of Lod as a character, as a narrator, in order to challenge the hegemonic modes of the story.”

Friedland doesn’t see the banning of the film as an isolated event. After all, she observes, works of art, usually books, are also boycotted in the United States. Accordingly, for her, cancellation of the screening is “part of a more widespread tendency, in a worldwide movement toward fascism. It’s not really surprising that the Ministry of Culture in the Likud government would want to prohibit the showing of a film like this at the present time,” she says.

“In a certain sense we waited for it to happen,” Friedland continues, “and after it did it was clear to us that we needed to get this story out, that it was important for people to know that a film about the violence inherent in the founding of the State of Israel – that is, the violence that was an integral element of the process of its establishment and that continues today as well – is banned for viewing now. Especially now, when the Nakba is continuing before our eyes in the form of the genocide in Gaza, the banning of this film tells a broader story, about what sort of history the State of Israel is willing to let its citizens see.”

Among the most controversial elements in “Lyd” are naturally those relating to the massacre the IDF did or did not perpetrate in Lod. The mass expulsion and the looting of property owned by the fleeing Palestinian residents are not in dispute; they are backed up by testimony from both Israelis and Palestinians who were participants in or witnesses to the events described in the film.

As to the more complicated issue of the massacre, the filmmakers provide testimonies of Palestinians who alleged that the IDF killed some 200 people sheltering in a local mosque. But testimonies from the Palmach – the strike force of the Haganah, the pre-state Jewish militia – who were fighting in Lod and elsewhere, though they mention killing as well, even of innocent civilians, generally present different versions of the events.

Shmarya Guttman, who was a commander in the force that captured Lod and subsequently the city’s military governor (and later a noted archaeologist), relates in his testimony in the film (taken from the Palmach Archives) that hundreds of men, women and children obeyed the army order to assemble in a local mosque and church.

“Bombs started to be thrown from the mosque at our guys,” he says. “I was asked what should be done, I said ‘It’s permitted to shoot into the mosque’… From a place where bombs are being thrown you have to eliminate it… It’s true that a few victims from the residents fell… There were no children and women there.”

Moshe Green, a member of the Palmach, stated: “And then the doors were opened. I burst in with a squad with grenades and submachine guns, and afterward there was quiet. People had amassed inside, I don’t know how many, and some of them were hit. Most of them were hit from this action, because what the PIAT [an anti-tank weapon] left to do, the grenades and the submachine guns did afterward.”

“With regard to the expulsion of the inhabitants of Lod, this is perhaps the only case among the series of expulsions in 1948-1949 about which there is no dispute among researchers,” notes historian Adam Raz, who does not appear in the film. “There was even a real-time discussion about it in the government. It’s the most documented expulsion, and there was also widespread looting there.

“With regard to the massacre,” Raz continues, “one of our problems as researchers is that there is classified documentation that the state is withholding, and another problem is that there is a whole continuum, from killing to massacre. If you ask me whether there was an organized massacre in Lod – there wasn’t. What did happen is that, within an extremely chaotic and violent situation, the IDF opened fire and apparently fired a few shells into a mosque in which there were Palestinians, some of them fighters and others [civilians].

“It’s clear,” he says, “that a very violent event occurred there, and it’s clear that the IDF used disproportionate force and didn’t give two hoots about Palestinian lives. But it’s not the same brutality that took place in Tantura, in Al-Dawayima, during Operation Hiram. There’s a difference between lining up people and shooting them in the stomach, and firing a shell into a building with people inside.

“Estimates are that 250 Palestinians were killed on that day [in Lod]. But the historians are divided over the issue of the massacre. Some say that’s a Palestinian libel, others insist it was a massacre in every respect, while yet others hold a view that’s somewhere in the middle.”

For his part, Younis stresses that it was important for him and Friedland to integrate Palmach testimonies into the film, and not make do only with Palestinian witnesses, so as to strengthen their case in the eyes of Jewish viewers.

Younis: “Jews, not only Israelis, grow up with disinformation and all kinds of historical distortions, to the effect that not only was there no massacre, but that in 1948 the Arabs left of their own volition. But I don’t know a lot of people who just think, ‘Ahh, yallah, I’ll leave my home voluntarily and I’ll go somewhere, without money, without anything, and maybe also die along the way.’ People don’t do things like that unless they’re expelled or their lives are threatened.

“Or there’s this lie that the Jews came to this land to make the wilderness bloom. What wilderness? My grandmother was a wilderness? What is that nonsense? It’s simply a blatant lie. So the film shows that there was life in Palestine before 1948, and that Lod, which is today known as a ‘real hole’ – and I’m allowed to say that – was before 1948 one of the important Palestinian cities.

“What the Zionist movement did was simply to empty out the Palestinian cities, because urbanization and colonialization don’t go well together. And because history is written by the winners, there will be some who will claim that there was no massacre, there was no expulsion and that the Jews made the wilderness bloom. But that’s not so, and the film shows it.”

On the one hand, Younis says that cancellation of the Jaffa screening of “Lyd” is not the end of the struggle, because there will be other attempts to show it in Israel. On the other hand, he says it’s not so important for Israelis to see it.

“I don’t care what Israelis think, it’s of no interest to me,” Younis says. “We also didn’t translate it into Hebrew – it’s only in English and Arabic – because I don’t care if Israelis see it. I have no hopes from Israeli society – not from Israeli intellectuals, not from Israeli media people, not from anyone. And I have no expectations from you, it’s over.

“After ‘On the Other Hand,’ I still had a certain desire to go back and do things and work, but I no longer have any such desire. The Israeli media is cooperating in hiding the truth from the Israeli public – most Israelis don’t know what’s going on in Gaza. [U.S. President Joe] Biden said early on in war, ‘I don’t believe these numbers.’ But we know those people! We talk to them, we see the images!”

If it’s not important for you to have Israelis view the film, and you don’t care about the Israeli media, why are you talking to me?

“Because of the ban on the screening. Because now it’s starting to become an issue that is far bigger than me: an issue of freedom of expression. And I have a lot of Israeli friends, I live in Israel, it’s important for it to be possible to screen films. Today it’s me, tomorrow it’s other creative artists. And if people are shocked now at the fact that the screening of my film was blocked, then I do want them to hear what I have to say and to understand why.”

* * *

A spokesperson for the Israel Police stated in response: “Contrary to what is alleged here, in the wake of a complaint submitted to the police by the Film Review Board maintaining that the film did not receive the board’s authorization as stipulated in the law, and in accordance with film review regulations, the owner of the venue arrived at the police station and it was made clear to him that, by law, he must arrange the public screening of the film with the board. Any other allegation is untrue and misleads the public.”

The Ministry of Culture declined to comment.

Sheren Falah Saab contributed to this article.

This article is reproduced in its entirety