Malnutrition, illness and death – the routine for Palestinian prisoners at Israel’s Megiddo Prison

Megiddo Prison

Hagar Shezaf reports in Haaretz on 6 July 2025:

In the living room of a perfectly nice apartment in Nablus, a thin young man sits on a faded brown sofa, smoking a cigarette. His hair is cropped short, his hands thin and bony, and beneath his large eyes are dark spots. They hint at what lies below. His legs are covered with dense, red-gray marks of various sizes – evidence of recurring scabies infections. These have been part of his daily life in recent months, alongside other illnesses.

Meet Ibrahim (real name withheld because he’s a minor), 16, recently released from Megiddo Prison. His appearance, the prison parole board noted, is “difficult to look at and a cause of great concern.” To complete the picture, one must listen to what he and his mother say. “When he was released, he looked like a mummy, like it wasn’t really him,” she recounts. “We didn’t recognize him.” She sits by his side, never taking her eyes off him.

In a picture his mother shows that was taken when he was released, about a month ago, Ibrahim looked far worse. Even now, his hands betray his thinness, little more than skin and bones. Alongside scabies, he suffered violence and acute symptoms of intestinal disease, including fainting spells.

His medical and legal documents, together with his testimony, constitute only a small part of a much greater body of evidence from prisoners – both adults and minors – who have suffered similarly in Megiddo. One of them, Waleed Ahmad, 17, died there in March. According to multiple accounts given to Haaretz, medical neglect and poor nutrition are only two of the many problems with prison conditions.

A healthy teenager, once

Ibrahim was arrested in October 2024. As part of a plea deal, he was convicted of throwing stones (which caused no damage) and sentenced to eight months in Megiddo, a facility operated by the Israel Prison Service. Upon entering the prison, he weighed 65 kilograms (143 pounds), a medical exam showed. Within a few months, his weight dropped to 46 kilograms. But Ibrahim says his medical file didn’t fully reflect the severity of his condition. At times, he weighed even less than that, he says.

A medical opinion that was written by a pediatrician (on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights) suggested “a grave medical picture that includes malnutrition and life-threatening underweight,” according to the parole board. His body mass index, BMI, was 15.2 (a minimum normal begins at 18.5). Laboratory tests also showed that he suffered from anemia.

Nobody’s stomach was full in prison. They would bring one plate of rice for 10 people. It was enough for one, but we all shared it.

Attorney Mona Abo Alyounes Khatib, who represented Ibrahim on behalf of the Public Defender’s Office, presented the medical opinion to the parole board. The board found Ibrahim’s medical condition “unusual and severe” and noted that the Prison Service officer responsible for prisoners’ welfare had not detailed his medical condition in her letters to Abo Alyounes. The officer only mentioned that prison authorities were aware of his condition and that he was being treated. The board, after shortening his sentence by 11 days, noted that “the harsh imprisonment conditions that the prisoner endured cannot be ignored.”

But Ibrahim isn’t “unusual.” Haaretz has obtained affidavits from four other inmates in Megiddo who reported similar medical problems over the past few months. Physicians for Human Rights has dealt with another five cases of prisoners with similar issues. Additional affidavits obtained by Haaretz are about the measly amounts of food served to prisoners and rampant scabies, a hard-to-avoid skin disease for anyone serving time at Megiddo.

And there is also the story of Waleed Ahmad. In March, he collapsed in the prison yard and died. A doctor who attended his autopsy on behalf of the family reported that Ahmad had almost no fatty tissue left in his body, suffered from colon inflammation and was infected with scabies.

Haaretz asked the Health Ministry, which oversees the National Institute of Forensic Medicine, whether the autopsy led to any action. The ministry refused to provide details, only noting that “as required by law, unusual findings are forwarded to the relevant authorities.” The National Prison Wardens Investigation Unit at the police is still looking into the death.

Megiddo Prison. ‘They handcuffed us and their dogs walked in front of us barking while they kicked us’, Ibrahim says

Megiddo Prison, located off Route 65 between Umm al-Fahm and Afula, may be an extreme case, but at least some of the problems that exist there plague other prison facilities that hold Palestinian detainees and prisoners. According to Physicians for Human Rights, as of last month, scabies is rampant in the Ketziot, Ganot and Ayalon prison facilities. In addition, a petition over reduced food rations for security prisoners (the Israeli term for most Palestinian prisoners) includes affidavits from inmates testifying to severe weight loss in multiple facilities. Lawyers say Megiddo, however, is the “worst of the worst” in almost every category.

When it comes to death behind bars, Megiddo ranks second only to Ketziot. Five people died at Megiddo – Waleed Ahmad and four adults – compared with seven at Ketziot. But all of these are part of a broader statistic: According to the Palestinian Prisoner’s Club, in the past 20 months, 73 identifiable prisoners and detainees have died in military and Prison Service prisons. As for Megiddo, in two cases, autopsies revealed signs of possible violence.

The prisoners speak little, if at all, about the violence, fearing the guards will hear directly or indirectly. ‘There was someone who once spoke in court about the guards, and then they beat him,’ Ibrahim says.

The first case is that of Abd al-Rahman Mar’i, a resident of Qarawat Bani Hassan in the central West Bank, who died in November 2023. His body bore signs of trauma, including broken ribs and a broken sternum. A prisoner who was with him at the time and has since been released, told Physicians for Human Rights that Mar’i had been severely beaten in the head before his death.

The second case is that of Abd al-Rahman Bassem al-Bahsh, a Nablus resident who died at Megiddo in January last year. His body bore bruises on the chest and abdomen, as well as broken ribs, a damaged spleen and severe inflammation in both of his lungs. Investigations into both deaths are ongoing and remain under a gag order. What is known is that these two cases are not being investigated by the National Prison Wardens Investigation Unit, meaning that the prison guards are not suspects.

The allegations of violence by prison guards come as no surprise to Ibrahim, who says it is routine within the prison walls.

“They would make us kneel at the back of the room, tell us to put our hands on our heads, then come in, spray gas in our faces and beat us with batons all over our bodies,” he says. “Once, they came in and hit me in the head and mouth with a gun, dislocating my jaw.” Another time, he says, one of the units of the Prison Service came in and beat the prisoners, sprayed them with gas and then dragged them to the prison yard, where they lay for about an hour in the rain.

“They handcuffed us and their dogs walked in front of us barking while they kicked us,” he recalls. There were other cases, he says. In one incident, he was beaten so severely with a club that it broke on his body. In a Haaretz report by Josh Breiner last September, other examples were cited.

Further evidence of abuse appears in a complaint from September by the Hamoked Center for the Defense of the Individual, filed on behalf of another underage Megiddo prisoner with the police’s Prison Wardens Investigation Unit. “The violence is so severe that the prisoners in the cell are in constant fear of what’s to come,” the complaint states. Guards enter cells during roll call and assault inmates with fists or clubs. The underage prisoner noted that he was once beaten in the stomach – where he had previously undergone surgery – until he lost consciousness.

Scabies

The prisoners speak little, if at all, about the violence, fearing the guards will hear – whether directly or through other inmates – and retaliate. “There was someone who once spoke in court about the guards, and then they beat him,” Ibrahim says. After Ahmad’s death, he adds, the violence decreased but didn’t stop.

These accounts are not confined to a specific period; they occurred both in the first months of the Gaza war, when Deputy Commissioner Muweed Sbeiti ran the prison, and in later months, under the command of Deputy Commissioner Yaakov Oshri.

One plate, 10 people

The interview with Ibrahim occurred on his first day back at school after his release from prison. An 11th grader who has spent most of the past year learning mainly about how to stay alive, he sums up his experience in prison with one word: “torture.” It’s a word that only partially captures what his sickly appearance and the memories he wishes he could erase reveal.

His may be an extreme case, but throughout the interview, he repeatedly says that other prisoners have endured the same things – some more, some less. “Nobody’s stomach was full in prison – not just mine,” he says. “They would bring one plate of rice for 10 people. It was enough for one, but we all shared it.”

This was a typical dish for a midday meal, he explains. Other meals weren’t much better. Breakfasts, for example, consisted of a single plate of labneh (creamy cheese), jam, bread and a vegetable – not for one person, but for 10. “And there wasn’t enough labneh to cover the bread,” he recounts. Because of the constant shortage of food, he says, the prisoners would combine everything, mix and share. A little bit for everyone and there weren’t any leftovers. “I would ask the guards for more food, but that was pointless,” he adds, noting that he would go to sleep hungry every night.

The only thing that rivaled the meager portions was their poor quality; sometimes, the salad vegetables were rotten, the rice undercooked. Similar descriptions came up in the testimonies of two other minors held at Megiddo. They told their lawyer that each dish in the meals amounted to about two to three tablespoons.

To some extent, these testimonies could have been expected – a result of National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir’s policy, which, after October 7, introduced dramatic changes to the living conditions of Palestinian prisoners in Israel. Among other measures, they were prohibited from accessing prison canteens, dishes and cooking equipment were removed from their cells and a directive to reduce their food portions to the legal minimum was issued.

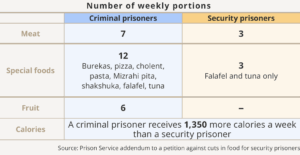

Last August, after the Association for Civil Rights in Israel filed a petition against the policy changes, the Prison Service claimed it had increased portion sizes. Appended to the reply was an updated menu comparing the food provided to security prisoners with that given to criminal inmates. An examination of the two showed that Palestinian prisoners receive half the amount of meat, no fruit, and no sweets aside from jam – unlike their criminal counterparts. The difference between the two menus submitted to the court by the Prison Service amounts to 1,300 calories a week per person.

In their reply, the petitioners argued that the law does not permit such a difference between the two groups. (The case is currently being considered by the High Court.) However, testimony from two minors at Megiddo prison indicates that as of early this year, even the meager menu the Prison Service had presented was not being provided. Most importantly – as the prisoners’ testimonies consistently make clear– they were always hungry.

And there is an additional issue. Until the war broke out, each youth wing in the security prisons had an adult prisoner who was in charge of distributing food. However, another of Ben-Gvir’s policy changes eliminated this arrangement, transferring the responsibility for distributing the food to the minors. According to Ibrahim, these young prisoners tended to steal some of the food for themselves – further reducing what little was left for the others.

Still, the meager portions and poor food quality aren’t even the biggest part of the story. The illnesses Ibrahim suffered were no less severe, to say the least. Along with the scabies he contracted several times, he suffered from an intestinal disease, contracted in prison. “I lay on the bed unable to get up,” he says, describing his condition last March, about two weeks into Ramadan. “I ate some bread, and an hour later I couldn’t hold it in – I soiled myself. I wanted to get up to go to the toilet, but I couldn’t. I slept all the time and didn’t eat anything.”

Nutrition for criminal prisoners compared to security prisoners

Five of his nine cellmates suffered from the same symptoms. “The medics would come to our wing, look through the window, give us some Acamol [Paracetamol] and say: eat bread and plain rice,” he says, describing the medical care during the first days. Other prisoners gave similar descriptions in their testimonies. During the months of the war, Acamol became the default response to most complaints – while hospital transfers were rarely even taken into consideration.

One apparent exception is the case of Zaher Shushtari, 61, who was placed in administrative detention – detention without trial – on the grounds of membership in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Shushtari, who suffers from multiple sclerosis and diabetes, became severely underweight during his detention and was finally transferred to the Prison Service medical center. However, this didn’t happen just because of his chronic medical conditions. It was only after Haaretz revealed in May that he had not received necessary treatment – and had not been taken to the clinic despite suffering from scabies – that the Prison Service changed course.

The medical opinion submitted in Shushtari’s case indicated that he also suffered from symptoms of a digestive disease – like those described by Ibrahim – including diarrhea and weight loss (others had symptoms that included dizziness and fainting too). Behind bars, Ibrahim says, they called it “the amoeba.” Prof. Amos Adler, a physician who specializes in clinical microbiology, did not name a specific illness, but based on the information in his possession, concluded that there was a high probability of an outbreak of a contagious intestinal disease. In an appeal to the Prison Service by Physicians for Human Rights – Israel, he wrote that the documents indicate that possible contributors to the problem were crowding, inadequate nutrition and poor hygiene.

Ibrahim’s testimony reflects this. According to him, even before the intestinal disease and the drastic weight loss, there was the scabies. The spread of the contagious skin disease in Israeli prisons is no secret; in late 2024, the Prison Service acknowledged in response to a petition that about 2,800 Palestinian prisoners had contracted the disease. Prisoners are a high-risk population for scabies because of the crowding in the cells. Most people contract the disease through contact with an infected person or from sharing items with an infected person in unhygienic circumstances. The Prison Service estimated that many of the inmates had already contracted the disease while in the West Bank or the Gaza Strip. Regardless, the conditions in which they were held in Israel, as evidenced in multiple testimonies and documents, did not help.

Ibrahim says he contracted scabies almost immediately upon entering Megiddo prison. “The itching began in the very first week. First, on my hands, and then on the rest of my body. It itches and then hurts like death. There was one prisoner who had scabies on his hands, and it hurt so much he couldn’t even hold a tissue.”

Megiddo Prison. A 17-year-old detainee says he was examined by a doctor only after another young prisoner died.Credit: Alon Ron

He says that most of the time there were 10 prisoners in the cell, but only eight beds – so at any given moment, two had to sleep on a mattress on the floor. Those who managed to snag a bed, mostly didn’t get a sheet, and had to sleep on the bare mattress. Somehow, Ibrahim had a sheet – but it wasn’t much more hygienic. “They wouldn’t ever wash the sheet,” he says. “Never.”

He did receive treatment – pills and bandaging with an ointment, and once a cream in a plastic cup – but the effectiveness was short-lived. The poor sanitary conditions and the rampant spread of the disease among the prisoners ensured he was infected, he says, a second and a third time.

Ibrahim’s descriptions, along with those of other prisoners, suggest that scabies and intestinal disease spread simultaneously through the prison, with many prisoners suffering from both at once. “Waleed [Ahmad] also had the amoeba. That’s what he died from,” hypothesizes Ibrahim. “I saw him. He went out the door of the room and he was so, so thin. We greeted each other. He was walking in the yard, and he fell on his face and blood started flowing from his mouth. The medics came in and took him away on a stretcher and he didn’t come back.”

Before he came down with the intestinal disease, says Ibrahim, Ahmad was healthy, apart from the scabies. His death sent shockwaves through the prison. Suddenly, says Ibrahim, attention was paid to those who had “the amoeba.” Two prisoners were taken to the Emek Medical Center in Afula (“We thought they had died,” Ibrahim says, “but in the end they came back”). He himself was first seen by a doctor and later sent to the prison infirmary several times, where he underwent blood tests and was given a transfusion of liquids. At no stage was he taken to a hospital.

He was, however, transferred to a specially designated cell for those who had significantly lost weight. There were 10 of them there as well, he says, but in this cell they were required to eat under the watch of the guards, each from an individual plate. Still, he says, the quantity of food remained as it had been, as did its quality.

An untreated epidemic

The names of the speakers may change, dates may differ, but the descriptions remain strikingly similar. Attorney Riham Nassra, who regularly represents Palestinians in the military courts, visited Megiddo Prison throughout this period. One of her recent visits was in April, when she met Nidal Hamayel, a 55-year-old administrative detainee who had been held there since last September.

His appearance told the whole story. “I was shocked when I saw him come into the visitation room,” Nassra says. Just two months earlier, she says, he had complained about the meager portions and being constantly hungry, but his condition looked by and large all right. This was not the case now. He had shed a lot of weight and was pale, emaciated, weak and scrawny, in a sickly way,” she describes. “He could barely walk, and was wearing filthy clothing.” Hamayel told her that since March he and other inmates had begun to develop severe abdominal pains, diarrhea, loss of appetite and suffered from fainting spells. “I’m frightened by what my body looks like when I shower,” he told her, according to the statement she wrote at the end of the visit.

Although Hamayel was examined by a doctor several times, he was not referred for additional tests and only prescribed a transfusion of liquids and painkillers. Like Ibrahim, he suffered drastic weight loss. When he was arrested, he weighed 86 kilograms, as noted in his medical file, but by February his weight plummeted to just 60 kilograms. The Prison Service claims his weight hardly changed between February and April, but Nassra believes he had become noticeably thinner during that period.

In a petition she filed to the Nazareth District Court concerning Hamayel’s case, Nassra noted that she had also visited two other prisoners at Megiddo who were suffering from similar symptoms, had not received treatment and had been told to drink water by the medic. The petition also noted other aspects of Hamayel’s detention conditions. For example, according to him he had only one pair of underpants, which he had been wearing continuously since September, and a single set of winter clothes. Moreover, he had no toothbrush, toothpaste or towel.

No ruling has yet been issued in the case, but the court has ordered the Prison Service to have Hamayel examined by a physician. In May, Nassra learned that her client had recovered from the intestinal disease – though he hadn’t received any treatment. “He still says he feels exhaustion and dizziness,” she said, “and he gets tired all the time.”

Another of Nassra’s visits to Megiddo is described in a statement recently submitted to the court as part of a petition by the Association for Civil Rights, demanding to provide adequate amounts of food to prisoners. “The detainee sat throughout the visit shivering with cold. He looked gaunt in an extreme and sickly way, and he said he was very hungry,” Nassra wrote about an administrative detainee she met in February. She was not surprised when he told her he weighed 48 kilograms.

A year earlier, he had already filed a complaint through Hamoked – about the inadequate food provisions and its poor quality, sometimes even insufficiently cooked. In its reply at the time, the Prison Service said he was receiving three meals a day – but offered no specifics on what the meals actually included or the identity of the dietician overseeing them.

In May, the growing number of intestinal disease cases and drastic weight loss at Megiddo Prison prompted Physicians for Human Rights to send a sharply worded letter. This was sent to the Prison Service’s legal advisor, Eran Nahon, and its chief medical officer, Dr. Liav Goldstein. In the letter, attorney Tamir Blank called on the Prison Service to take action to prevent the spread of the disease, the symptoms of which “are common to dozens of inmates.” In his response, Dr. Goldstein wrote that the claims are known, describing it as “a number of incidents concentrated at one prison facility several months ago”. He stated that the Prison Service had implemented all the necessary measures, the number of incidents had decreased significantly and that there are no new cases at present.

However, just two weeks earlier, when attorney Nadia Dacca visited two minors at Megiddo Prison, their accounts indicated that little had changed. Both had said they had gotten sick, they had not been treated and they recovered on their own. “I didn’t receive any medication from the prison authorities. Some prisoners had Acamol [a painkiller] in the cell, so I took some,” one of them told the lawyer. “I recovered after suffering for a long time and without receiving any medical care – while knowing that a prisoner in my block had died of it,” he said, referring to Waleed Ahmad.

The prisoner estimated that he weighed 62 kilograms at the time of his arrest, and by the time he spoke with the lawyer, his weight had dropped to 53 kilograms. He noted he has two pairs of trousers, two pairs of boxer shorts and a short-sleeved shirt to wear. “I have a mattress without any cover, and this adds to my sickness, because I touch the mattress directly and can’t wash it,” he said.

The second youth Dacca visited, a 17-year-old administrative detainee, described the same all-too-familiar symptoms. He also said he had been examined by a doctor only after Ahmad died, about a month after he had contracted the disease. “My body was very weak, and I couldn’t walk,” he said. During the hearing to approve his administrative detention, he testified that he suffered from scabies and had lost 30 kilograms. The judge ordered the authorities to refer his case to the prison medical staff to ascertain his condition. He later described similar conditions: a mattress without a sheet, lack of clothing and pills that didn’t help. “They are still not taking the scabies seriously,” the youth explained. “The medic laughs at me.”

The Prison Service responded by stating that it “acts in accordance with the laws and procedures, while maintaining the well-being, safety and rights of all the inmates at the facility – including the minors. All medical care is provided based on a professional medical opinion, in accordance with Health Ministry regulations and under the supervision of doctors and professionals acting within the facilities and outside of them. Insofar as a complaint of faulty treatment arises, it is examined by the personnel authorized to do so.”

It further stated that “in every case of a prisoner’s death, the Prison Service reports it immediately to the appropriate investigative authorities – in accordance with the circumstances of the event. At the same time, an internal investigation is launched to ascertain the circumstances of the case, in accordance with procedures. The Prison Service will continue to act responsibly and as stipulated by law, while maintaining human dignity, public security and law enforcement.”

This article is reproduced in its entirety