For displaced Gazans, leaving Rafah is moving from one hell to another

Gazans who fled Rafah for Khan Yunis on 6 May 2024

Amira Hass reports in Haaretz on 8 May 2024:

According to Palestinian reports, 22 Palestinians, among them eight children including babies, were killed by Israeli bombs and shells in eastern Rafah overnight into Monday. On its website, the Wafa news agency posted a video showing mothers weeping as they said their last goodbye to their children, who were bound in white cloth.

In Israel, the bombing was reported as a response to mortar shelling from the Gaza Strip that killed four Israeli soldiers and wounded 10. The conclusion of the people in Rafah wasn’t that the bombing was a response to the soldiers’ deaths or to target the source of the mortar shelling. It was revenge – and a promo for an Israeli ground invasion.

All this comes on top of the usual horror, despair and exhaustion, as well as the knowledge that anyone could be killed at any moment, or lose an arm or leg, or bury a 6-year-old child.

The bombing was also seen as an order for residents to uproot themselves from their homes – the same message provided by the leaflets that Israeli planes dropped over the area or the voice messages and text messages from unknown numbers. The highly neutral term “evacuation” doesn’t convey a fraction of the dread, rage and exhaustion that the residents are experiencing in Rafah at Gaza’s southern tip.

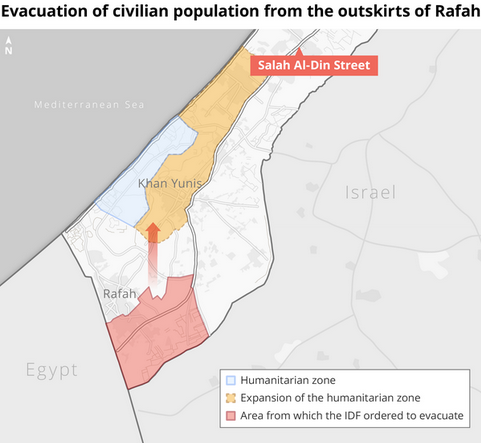

This is the new exodus that Gaza residents began Monday on foot, in carts, minibuses and sputtering cars, and on bicycles laden with mattresses, blankets and meager amounts of clothing and food. The evacuees set out from Rafah’s eastern neighborhoods for parts unknown to the north or west. Their options are to head north toward the ruins of Khan Yunis, or the coastal strip of agricultural land at Muwasi, which lacks water or sewage facilities but which Israel insists on calling a humanitarian zone.

Following Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh’s dramatic announcement Monday evening that his organization had agreed to a cease-fire, will the tens of thousands of fleeing Gazans turn around? Will the procession of flight be halted?

At this stage, what’s certain is that Haniyeh’s statement and Israel’s counter-statement – that Hamas is engaging in deception – have added to the confusion, the lack of information and the difficulties in deciding what to do. All this has been dominating life in Rafah against the backdrop of the Israelis’ frequent statements that they’ll invade Rafah too. And all this comes on top of the usual horror, despair and exhaustion, as well as the knowledge that anyone could be killed at any moment, or lose an arm or leg, or bury a 6-year-old child.

Evacuation from Rafah

Al-Jneineh is one of Rafah’s eastern neighborhoods that was shelled Sunday and whose residents the Israeli army ordered to leave. A number of my friends and their families have been living there. Most of them had to move there from Gaza City and the Jabalya refugee camp in northern Gaza about six months ago. Others chose to live there 20 or 30 years ago.

The trees and greenery of the area were gradually replaced by concrete homes of all sizes. Young people from the Shabura refugee camp worked hard, saved one penny after another and went into debt so they could buy a plot of land to build a house and move from the narrow alleyways and crowded homes of a refugee camp devoid of sunlight.

Now crowding in with al-Jneineh’s residents are their relatives who are being uprooted a second, third or even fourth time. Over the past seven months since the outbreak of the war, they have felt a bit fortunate even though in al-Jneineh, as in Rafah’s other neighborhoods, airstrikes have destroyed homes and killed the people in them.

Still, al-Jneineh’s residents managed to remain in their homes rather than live in tents, and they also had essential household supplies such as blankets, clothing, mattresses and kitchen utensils. They never had to wait in lines of 300 to 400 people to use a bathroom, as has been the case in schools that have become shelters. For them, this number has been between 10 and 30 people, depending on the size of the family.

Will they also become a statistic this week, included in the numbers for the Gazans who have lost their homes? Will they find a tent? Will they have to sleep outdoors?

Their parents were children when they were expelled from their villages or from Majdal – now Ashkelon – or Isdud (Ashdod) in areas that became the State of Israel. Some of those refugees are still alive. They haven’t forgotten being uprooted and losing their homes. They need special care and hope to die so they aren’t a burden on their children and grandchildren.

The families of two friends – Dalia and Yakub – live 200 to 300 meters from each other. On Monday, Dalia said they were “inside the map,” meaning that their crowded home, where her children and her husband’s extended family have been staying, was inside the area to be evacuated. So they needed to pack what little they had and flee.

Yakub said on Monday that his house – with four families – wasn’t inside the map and he was waiting to see what would happen. He said he didn’t think Dalia’s house was inside the map, so Dalia and her family wouldn’t have to flee. Or not yet.

But Rafah’s only hospital, Yousef al-Najjar, is inside the map, Yakub wondered whether all the patients, displaced people who are staying there and medical staff would have to leave, and whether anyone who stays behind will be killed and buried in a mass grave.

A woman in Gaza mourning a child killed in an attack on 6 May 2024

Dalia said she wasn’t sure that Yakub was right that the house of relatives where she’s staying is outside the map – and nobody really understands the map anyway. They don’t know what to do – whether to pack, what to pack and how to carry the family’s grandmother.

“We’re 500 meters away,” Dalia said, referring to the area where people are being evacuated from. “What’s 500 meters? When there’s shelling or bombing, the shrapnel will reach us. We don’t know where to go. We’ve thought about going to the center of the Strip, but there’s no truck to take us. We don’t know what we can do anymore.”

Our phone conversation got cut off, but in a voice message, Dalia said that cellphone reception is very poor and they’re constantly hearing bombing and shelling. On Monday night, while the Israeli army occupied the Palestinian side of Rafah crossing, the constant shelling and bombing didn’t let the family sleep for a moment, she wrote.

Our mutual friend Saleh, who was uprooted about six months ago from the Shati refugee camp, couldn’t bear the uncertainty and the constant fear of an Israeli ground invasion. Two months ago, he moved to a neighborhood north of Khan Yunis that had relatively few homes.

“I didn’t want to happen to us what happened the first time we were uprooted, when we fled the house in the middle of the night and left everything behind us including blankets and mattresses,” he said.

Initially his wife was afraid to move to their vacation hut because the toilet isn’t in the house. She was afraid that Israeli drone operators would decide that anyone outside the hut at night was a Hamas gunman and kill him or her. But the fears of an invasion of Rafah took precedence over a drone hit.

“It’s not that we’re alive. This isn’t a life. The streets are full of sewage and garbage. We have no water in the hut,” Saleh said. “Even for someone still drawing a salary, you can’t make a withdrawal from a bank and have to spend almost a quarter of it on money-changing fees. A gas canister costs 400 shekels [$108]. We’re not working. The children aren’t going to school. We’re just existing, and at any moment anybody could get killed. The hell is the same hell, whether here or in Rafah or Gaza City.”

This article is reproduced in its entirety