Death, martial law and censorship: A dark period in Israel’s history is shockingly relevant today

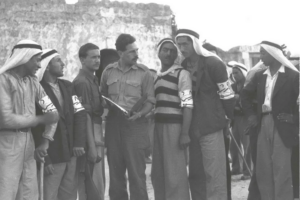

A still from ‘The Governor’, a new documentary by director Danel Elpeleg

Dahlia Scheindlin writes in Haaretz on 19 December 2024:

In a radio interview last week on Israel’s Reshet B radio station with Danel Elpeleg, the hosts asked Elpeleg about her grandfather, the subject of her prize-winning documentary film “The Governor”. The 35-year-old director explained that he had served as a military governor over Israelis in the early years of the state. Then, the hosts interjected, asking her to explain to their listeners what a military governor is.

The exchange takes a few seconds, yet it tells the story of the first 76 years of the country’s history – and possibly the story for decades to come. Elpeleg told me she never learned about that history in school or elsewhere, only from her family.

Most of the film documents the role her grandfather, Zvi Elpeleg, held as a military governor in the so-called Triangle area, a cluster of Arab towns and villages along the northwestern Israeli side of the Green Line. This military regime within Israel was established during the 1948-1949 War of Independence, and was technically dismantled in 1966; the martial law undergirding the regime was phased out in 1968.

Recently, South Korea couldn’t tolerate six hours of martial law. But in Israel, two decades of military rule have practically vanished from the country’s collective memory – that is to say, for Jews. Only Palestinians civilians were subjected to the regime. The experience has marked the relationship between Arab citizens and the state to this day, in ways most Israeli Jews have never tried to understand.

The regime in our midst

After the War of Independence, the Palestinian communities remaining in Israel were shattered, most displaced and dispossessed. The military government became an all-purpose system governing every aspect of their lives. An older Arab man who grew up under the regime explains in the film that the governor fulfilled the functions of “the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Education, the population registry… He had the power of life or death over people.”

The film paints the surreal scenes arising from that power. A grand home in Baka al-Garbiyeh, now dilapidated, served as the seat of the military governor in the 1950s. The actual owners of the home lived on the upper floors, and the army took over the ground floor. Arab detainees were held in the basement. Still photos capture the taut fear in their eyes, while their freshly-minted Israeli rulers look on with a confident, superior gaze.

Newspaper articles portrayed Zvi receiving villagers, weighing suspicions of petty theft, or criticizing the poor labor conditions of farmers. The archives document his rejection of an application to establish a cafeteria in a local primary school (he interviewed children and concluded that they ate well enough at home, meticulously listing their breakfast menus) and how he fielded applications of locals to purchase a donkey, a tractor, or to see a dentist.

The separation barrier at Baka al-Garbiyeh in 2009

Every night brought a curfew. An elderly woman recalls that she was 17 when she experienced labor complications. She waited all night “seeing death before my eyes,” until 5 A.M., when someone could ask the army for permission to take her to a hospital. One interviewee recalls a man asking for a permit for his sick son to see a doctor. The father waited for three days, and the son died, says the interviewee.

The film is overlaid with Elpeleg’s journey into her family history; not just as a sideshow. Her grandparents’ unhappiness suggests how a career of lording over people can infiltrate the most intimate of relationships. It’s hard not to see some connection between the military governor’s role, and her grandfather’s cold, suppressed or neglected emotional life at home.

From the personal back to the political, the military government sheds light – or dark shadows – on the Israel of today.

The regime’s authority derived from the Defense Emergency Regulations (DER) of the British Mandate. The colonial power enacted these rules in 1945 to suppress Jewish terrorists, reissuing the 1930s regulations that were used to suppress the Arab Revolt.

Some Arab citizens are still too fearful to give Elpeleg an interview. Palestinian historian Leena Dallasheh tells her that the generation raised under the military government, with its informants and collaborators, its theft of property and their freedom, could not fully exorcise its traces.

Pre-state Zionists hated the regulations. In “1949: The First Israelis,” Tom Segev quotes the jurist Yaakov Shimshon Shapira, who became the country’s first Attorney General and was later appointed Justice Minister, calling them worse than the laws of Nazi Germany, whose crimes were at least violations of the regime’s own laws. Moreover, said Shimshon Shapira, the British tried to reassure pre-state Zionists that the DER rules were meant for terrorists, not for law-abiding subjects of the Mandate, writes Segev.

The new Israeli state adopted the regulations wholesale for all Arab civilians subject to the military rule (which meant most of them). The colonial laws were carried over to modern Israel, where certain articles are still in force today, as a core legal tool of the occupation, and incorporated into Israel’s anti-terror laws.

Some Arab citizens today are still too fearful to give Elpeleg an interview. The Palestinian historian Leena Dallasheh tells her that the generation raised under the military government, with its informants and collaborators, its theft of property and their freedom, could not fully exorcise its traces. Elpeleg searches for her grandfather’s inner demons, while Dallasheh explains that her grandfather still lives in “a panic.” He is worried that her work as a historian and her political activism will cost Leena her freedom: “It’s the military government that built the insecurity, the lack of certainty that is part of our lives” – an invisible reality for most Israeli Jews living at their side, citizens of the very same state.

Engineering ignorance

Some would be happy for Israeli Jews’ ignorance of their history to continue. Elpeleg’s film is based on interviews she recorded with her grandfather while she was serving in the Israel Defense Forces, from 2007 to 2010. She worked at the now-defunct IDF magazine, Ba’mahane (On the Base), and thought Zvi’s story would make a good article. The military censor did not agree and blocked her piece from publication.

The censor didn’t explain its rejection. Most of what now appears in the film about the military government is known, documented by dogged historians such as Yair Bäuml, Leena Dallasheh, Shira Robinson, Tom Segev, Adam Raz, Gadi Algazi, and others. However, it wasn’t only the censor back then who got skittish.

Residents of the Arab town of Kalansua, who had been recruited as policemen in 1949, confer with an IDF officer after being issued police armbands

Last week, Shai Glick, director of a Jewish-only “human rights” group – an oxymoron – whom Haaretz once dubbed Israel’s “censor in chief,” decided he didn’t want the film shown at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque. It’s hard to overstate the foolishness; the film was already screened at this year’s Jerusalem Film Festival in July, where it won the Diamond Award for Best Documentary, and has been shown at other venues too. Besides, banning anything is a surefire way to raise interest.

But Glick is a self-appointed Israeli warrior against unsavory art (or what his group calls “terror-culture.”) It hardly matters that he hadn’t actually seen the film; Glick rushed to Israel’s Film Review Council, under the Culture Ministry, to tattle that “The Governor” had not passed the film censor’s approval. This time he didn’t get his way; the review board met and approved “The Governor” within one day, and the Tel Aviv Cinematheque screening went forward last Friday as planned. Other films have not been so lucky.

Why is there a film censor at all in Israel? Well, this body too is a holdover from the British Mandate, established in 1927 for the purpose of controlling what could be seen in the colonial era. Although its censorship role is mostly obsolete, again, the residual institutions of colonial rule linger in today’s Israel. The fate of the film is starting to echo the past mechanisms of control it portrays.

Woven into the present – and future

Similarly, the military apparatus governing Israeli citizens formally ended in 1966, but it never quite died. The DER powers were transferred to civilian bodies, the police and Shin Bet, recalls Dallasheh in the film, phased out only in 1968. By then, a new military regime had been established for the territories occupied in 1967. The military advocate general, Meir Shamgar, drew up the plans for the West Bank and Gaza already in 1963, literally copy-pasting from the DER (using scissors and glue, according to Yael Berda’s book, “Living Emergency”).

The personnel for the new post-1967 military occupation was experienced. Zvi Elpeleg, as noted, had already served as the military governor in the Triangle area. He also served in Gaza following the Sinai campaign; Nablus, Egypt (just west of the Suez Canal) and, finally, in southern Lebanon. He later became a prominent and respected historian of Palestinian national movements, wrote a book on Haj Amin al-Husseini, and in the 1990s became Israel’s ambassador to Turkey. The military advocate general from the 1960s, Meir Shamgar, who developed the legal basis for the occupation, become a Supreme Court justice.

Israel’s occupation rules Palestinians to this day, to varying degrees, by means of a legal system that includes the old colonial regulations and a labyrinthine patchwork of Jordanian, Ottoman, and post-1967 Israeli military law. Many of these are implemented by the Civil Administration, under the IDF. It is this body’s powers that Bezalel Smotrich, Israel’s current finance and settlement minister, is now seeking to absorb into civilian hands (his), completing the annexation of the West Bank, and further merging the permanent military occupation with the law and civilian arms of the of state.

Thus, the film is a glimpse of Israel’s possible future as well. Smotrich has been calling for the establishment of a military government in Gaza from the early months of the war. Even if a hostage-cease-fire deal is brewing, Defense Minister Israel Katz has promised that “we aren’t going to end the war,” and that Israel “will assume security control in Gaza” with “full freedom to act, just like in Judea and Samaria.”

Much of Gaza’s population has been herded to the south, while Israel is razing the north of the Strip for a reason that its ministers love to share: settlement and phased annexation. Who will govern the Palestinians there? Israelis – and Palestinians – know the drill.

Zvi Elpeleg died in 2015, but he left his insights for future generations. “People will have a hard time digesting just how wrong we were,” he says at the start of the film. “What do you mean?” asks granddaughter Danel.

Zvi tells her that nations prepare themselves for victory in war, “but they have no answer to the question of what they will do the day after the victory.” Later he wonders aloud how long a nation can control another people. He recounts Israel’s cyclical history of wars, conquest, and occupation with no end. “And that’s how victory is lost,” he says.

This article is reproduced in its entirety