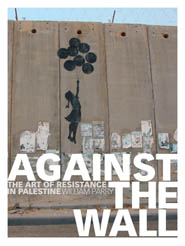

Against the Wall: The Art of Resistance in Palestine

The art of resistance

The art of resistance

Mike Marqusee reviews Against the Wall: The Art of Resistance in Palestine by William Parry (published by Pluto Press)

Forthcoming, Red Pepper, August-September 2010

When the state of Israel began constructing its “separation barrier” through the West Bank, it never anticipated that the wall would become a living gallery of resistance, crowded with images and words of defiance. This creative response to injustice is by nature impermanent (one day the wall will fall) and even now is subject to constant change as parts are added or effaced. Which is why William Parry has performed such a valuable service in documenting it.

Parry’s photographs vividly convey what he calls the “kaleidoscopic” impact of the artwork on the wall. There’s an amazing range of styles, from painterly expressionism through pop art parody and cartoon minimalism. Desperate pleas for help and solidarity (“EU, UN where are you?”) alternate with expressions of misery (“Dead city”, “No hope”), political indictments (“This is a land grab”) and dead pan, sometimes cryptic irony (“Here is a wall”, “I want my ball back!”, “Been there done that”, “Nothing to see here”). A white dove lies speared and bleeding. Eyes peer through barbed wire mesh. A raised fist holds a beating heart: “Your heart is a weapon the size of a fist.” There are donkeys, camels, flags, faces contorted with rage, people sniffing flowers.

The graffiti is in many languages and filled with echoes of faraway struggles. Ben Franklin is quoted (“Those who don’t stand for something will fall for anything”), as is Bobby Sands (“Our revenge will be the laughter of our children”) and Immanuel Kant’s first rule of enlightenment: “Sapere Aude!” (Dare to know).

Many of the artists make ironic use of the very structure on which they’re painting. A rampaging rhino seems to smash a gaping hole in the wall. A man prods a finger into a spot on the wall from which a network of cracks spreads outwards. “CTRL + ALT +DELETE” reads one large-scale slogan. Everywhere, the more polished artworks, many contributed by artists from abroad, are merged with casual, sometimes crude popular graffiti – which is as it should be.

Parry discusses the occasional tensions between international artists and locals. Banksy, who played a central role in organising the project, depicted a rat armed with a slingshot, the very low-tech weapon used by Palestinian youth in their confrontations with the Israeli state. Some people took offence at the implied comparison of these youth to rats; the image was wiped out and replaced with words: “RIP Banksy Rat”.

The book documents not only the art but the crime of the wall. Deploying hard facts and compelling vignettes, Parry chronicles the confiscation of land, the appropriation of water, the severe restrictions on movement, the daily harassment and humiliation, the destruction of jobs, farms, businesses, neighbourhoods and whole towns. The photographic and verbal evidence he presents leads to the inescapable conclusion that the purpose of the wall is not the protection of Israelis but the slow strangulation of Palestinians.

As a whole, the book gives due weight to both hope and despair. It shows Palestinians struggling, day in day out, as individuals and collectively, for their survival and their rights. And it documents the violent Israeli response to their non-violent protests, in which 19 Palestinians (with an average age of 19) have been killed, and 1500 injured.

One slogan that is found repeatedly on the wall is “To Resist Is To Exist”. This book allows us to see and feel what that means.