A unique programme for Jewish and Palestinian artists allows for a rare dialogue

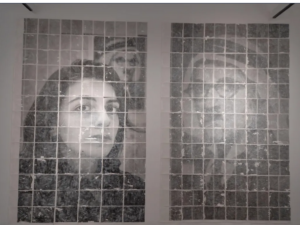

Baylassan M. Karim’s ‘Self Portrait – Thieba’

Sheren Falah Saab reports in Haaretz on 28 May 2024:

Last year, after completing her studies at the Midrasha Faculty of the Arts at Beit Berl Teachers Training College, Eram Aghbarih planned her next move. She registered for a residency program at the Givat Haviva Jewish-Palestinian education center created for artists who are just beginning their careers. Accepted into the program, she eagerly awaited it starting on November 1. “It was the right move,” she says. “The program lets you devote all your time to learning and deep examination of myself as artist.”

Hamas’ attack on southern Israel on October 7 stopped the plan in its tracks. The Givat Haviva complex took in evacuees from Gaza border communities, and the staff in charge of the program had to delay it. It was eventually launched in January, but by then, Aghbarih’s anticipation had been replaced by apprehension.

“I was hesitant about participating,” she says. “I’m an Arab woman with a hijab, and I didn’t know how people would react when they saw me. I’ve always felt a little scared in Jewish towns, but it’s recently become worse.” However, her previous familiarity with the institution eased her fears and encouraged her to persist.

The 23-year-old is one of 10 participants in the Givat Haviva Collaborative Art Center’s residency program. They are newly minted graduates of art schools. Half of them are Jewish, and half are Palestinian. For three months – early January to the end of March – they lived and created art together under the tutelage of experienced artists.

Their works are on display at the exhibition “Memories from an Imagined Space” at the Givat Haviva Art Gallery. Curated by Dalia Manor, it was on show until last week. “Despite the short amount of time, [the artists] managed to create fresh, meaningful works – and they will definitely develop further as they continue on their artistic paths,” says Manor.

The war in Gaza influenced the artists and their work, perhaps inevitably. “Since October 7, I’ve been asking myself what the place of art is in times like these,” says Noa Kurnick, a 25-year-old graduate of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem who was part of the program. “I have a twin brother who was drafted into the reserves [to serve] in Gaza, my younger brother is doing his mandatory service and my father is from a bereaved family. Everything felt very immediate on the personal level, and I decided to use my work ask questions about the blood-soaked situation we live in, war after war.”

An abstract work by Eram Aghbarih

Kurnick constructed a miniature model display made up of different items culled from around Givat Haviva. The display reflects the fragility of the situation and alludes to the experience of the current war and those that came before. “I found memorial books of fallen soldiers in 1967 from the kibbutzim, and my grandfather fell in that war,” she says. “I looked at the current situation through that lens. What end does this cycle of bloodshed serve? Whom does it serve? What and whom are we memorializing? What’ the meaning of the heroism we consecrate?”

Aghbarih says she only started to work on her project after a month and a half. “I was unable to express myself, even in the smallest ways,” she says. “I felt something inside that was blocking me.” She says that the guidance of the mentors provided support that helped her overcome the problem. “I realized I could use my creative techniques and incorporate performance art, which connects the material and spiritual worlds.” The exhibit includes two abstract paintings created by exhaling into a bowl of paint that is then spilled onto the canvas, as well as an installation titled “Red Blanket.”

“Ultimately, we’re human beings like everyone else,” says Anat Lidror, the director of the program. “We wake up with the news and what’s happening. Everything affects us. Each participant chose how to deal with the situation, and the program allowed them to decide to what extent they wanted to deal with the war.”

The exhibit also features a sound installation by Jonathan David, a 28-year-old musician and graduate of the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. He recorded and altered sounds from various places. During the residency, he spent a week on reserve duty and lost friends killed in battle. “I used what life put in front of me,” he says. “I told myself that I must deal with what’s there and not create with detachment. Every weekend, I would go to a different funeral.”

David’s work includes four suspended objects – a book, a military uniform jacket pocket, a stone and a cassette tape. Each object activates a different sound. “The book activates sounds from Givat Haviva,” he says. “The pocket – sounds from reserve duty. The stone – recordings of friends’ funerals. And the tape activates music. It was important for me to separate the experiences and to put each thing in its own compartment. It was like a therapeutic process.”

David describes the complexities resulting from sharing a space with the Arab artists. “I felt uncomfortable when I went to reserve duty,” he says. “I asked myself: ‘How do they see it? Do they care, do they not care?” He says the war became intermingled with social dynamics.

“I’m not sure if I emerged from the program more optimistic,” David says. “Right now, we have no perspective on October 7, on the war and on what’s happening in Gaza, and it’s hard to discuss the situation rationally. And talking about all these complexities within the group was the elephant in the room.”

However, he does recognize art’s ability to serve as a bridge. “Even though there’s a political context or another in the various works, we were able to separate it and set it aside,” he says. “We felt comfortable consulting one another while we were working.”

Someone else’s shoes

Ben Alon, a 25-year-old visual artist and graduate of Bezalel, illustrates in his photographic works the multilayered experience in Givat Haviva as a physical, expanding space, as a sociopolitical ideal and as a temporary home for the individual and the group.

“Not everything was perfect. It was walking a tightrope,” he says. “Besides the fact that it’s Jews and Arabs together, we come from different places in the country and different educational institutions. Each one arrives with a different set of tools and values, and we had to work to have a meaningful and beneficial conversation.” Despite the challenges, Alon sees his participation as an opportunity. “I was happy that this actually happened during the war, because it’s more important than ever to be together, to get to know one another and to talk about the conflict.”

A work in the exhibit by Baylassan M. Karim, a 28-year-old graduate of the University of Haifa, includes a portrait of herself on one side and of her great-grandfather on the other. Although she chose to focus on the personal sphere in her project, the complex atmosphere in the group affected her, too.

Part of Ben Alon’s ‘Haviva’ project.

“As Arabs, it was hard for us to share our feelings and emotions,” she says. “But this space that had been created allowed us to open up. It’s true that there were some moments of tension, but we managed to calm things down when that happened.” She recalls a discussion about the war with another two participants, a Jew and an Arab. “It wasn’t an easy conversation,” she says. “We touched on the painful issues for both sides and still managed to listen.”

The prolonged stay also entailed unexpected challenges beyond the war. “When you think about differences, you think about language [or] political views,” says Kurnick. But they also exist on a day-to-day level.” She recalls one occasion on which the Arab participants washed dishes with bleach. “It was something shocking to me, and they were in shock that we don’t wash with bleach.” Karim adds: “For a light meal, we Arabs made cheese sandwiches, and the Jews made a spring roll.”

The differences were revealed in other ways, too, Alon says. “I was also exposed to conflicts found within the Arab community,” he says. “I really saw the difference between the Arabs who come from the village and those who come from the city, and that’s no different from any other culture. We tend to simplify and generalize. Those are things I wasn’t aware of before.”

Kurnick says that the Jewish participants studied Arabic during the residency. “The hope for a better future doesn’t appear on its own,” she says. “You have to build it with your own two hands.” She adds that “the decision to participate in the program also means choosing life and a desire to live alongside one another. Dialogue and the creation of the shared space are essential for coexistence.”

Karim sounds a similar note. “For me, it reinforced my understanding of the importance of examining situations from different perspectives and being in someone else’s shoes. You have to preserve what we do have despite it all, and especially partnership between Jews and Arabs.”

This article is reproduced in its entirety