A Palestinian boy’s detailed drawing exposes a joint campaign of terror by Israeli army and settlers

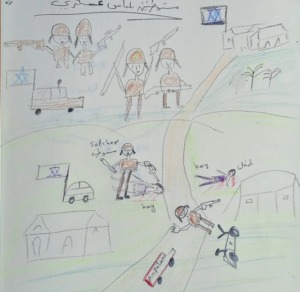

Jafar Rabai’s drawing, he calls ‘Settlers Dress Up as Soldiers

Nir Hasson reports in Haaretz on 31 March 2025:

To understand what happened at the village of Jinba in Masafer Yatta over the weekend, it’s best to look at a drawing by a young boy in this region of the southern West Bank. The work, which the boy Jafar Rabai calls “Settlers Dress Up as Soldiers,” depicts six soldiers with sidelocks, marking them as religious settlers.

In the drawing, a boy is lying on the ground with his head bleeding; another boy is lying on the ground as a soldier holds a rifle to his head. Another soldier is halting an ambulance, and the other four are brandishing their rifles.

The drawing is a good depiction of the events over the weekend, which started with reports of an attack on an Israeli shepherd – reports that triggered harsh reprisals by settlers and Israeli soldiers.

The blackboard in the little village school still bears the date of the 26th of Ramadan, last Wednesday. The school also fell victim in the attack – soldiers broke down its doors and destroyed dozens of desks and chairs.

In one classroom, they tore down a Palestinian flag from a wall and set it on fire in the middle of the room. Almost all the school’s windows were broken; someone even took the trouble to break the loudspeaker that sounds the bell. The soldiers also went to the small clinic next door that is visited once a week by a physician from Doctors Without Borders. The soldiers carefully destroyed furniture in the clinic, then they did the same thing to a sink and a water dispenser.

Jinba is one of the most remote villages in Masafer Yatta, where settlers and the military are most violent in their attempt to drive the people from their homes, on land the army wants for a firing zone. Many people in the village live in caves or use them for storage; the people make their living shepherding and in agriculture.

A West Bank village destroyed

The sequence of events began Friday. “A Jewish shepherd has been attacked. … Terrorists from the village of Jinba attacked the shepherd with clubs while he was out with his flock and wounded him,” the settlers said in a statement.

The announcement was accompanied by two photos of the shepherd with blood on his clothes and hands. But on Saturday, it turned out that this was no ordinary shepherd. In footage released by people from Jinba, the shepherd is seen driving toward two Palestinian counterparts on an all-terrain vehicle, before he attacked one of them. It’s unclear what happened next and whether the Israeli shepherd was indeed wounded by the Palestinian shepherds or someone who came to help them. Either way, reprisals by settlers quickly followed.

Shortly after the attack, around 15 young settlers covering their faces stormed the village armed with clubs. Footage shows them entering the first home and viciously beating 15-year-old Ahmed al-Amur, even after he fell down bleeding.

They then attacked Ahmed’s 64-year-old father, Aziz, who was struck several times and was left with a fractured skull, presumably from an iron bar. Next came his second son, Kosay, whose arm was broken. In the yard around the house one can still see bloodstains from Ahmed, while his father’s bloodstains are still in the adjoining cave.

A neighbor of the Aziz family, Leila Abu Younis, heard the screaming and ran over. “There were settlers there, maybe 15, veiled,” she says. “They attacked the boy and we didn’t dare go near them; we couldn’t do anything, but we saw there were soldiers in the distance and we cried out to them: ‘They’re murdering him, murdering him, get an ambulance!’

“One settler was standing between me and a soldier. The settler picked up a stone and threw it at me, and the soldier told him not to throw anything but did nothing. The boy was bleeding from his ears and mouth. His brother, with his broken arm, said to me, ‘Auntie, talk to him so he doesn’t fall asleep, so he doesn’t die.'”

‘One soldier asked me what I had there; I told him it was a baby, my granddaughter, and then he shouted so he would scare her. My daughter, 19, began to shake with fear. Her face went yellow.’

While the wounded lay bleeding and waiting for evacuation, dozens of soldiers arrived at the other side of the village and ordered all men in the area, 22 in all, to go to the square by the mosque. They were blindfolded and their hands were tied behind their backs.

The youngest detainee was 15. They were made to stand in line and were put on vehicles, at least one of which belongs to a local settler. The detainees were taken to a nearby army base.

Issa Abu Younis, Leila’s husband, quickly returned from his flock when he heard what was happening in the village, but he was detained by soldiers. “At the base, they put us in a big hole in the sand, handcuffed and blindfolded,” he says. “After a couple of hours, we were taken for questioning at Kiryat Arba” – a West Bank settlement. He says they fasted during the day, as they do all day during the month of Ramadan, “and they threw us there without water. They finally gave us one bottle, for 22 people. It wasn’t until 11 at night that they gave us more water.”

The police said in a statement that “22 suspects have been detained on suspicion of complicity in the incident” – the attack on the shepherd. But by midnight, 15 of them had been released with another seven left in detention until Thursday. And the story wasn’t over.

Leila Abu Younis invited her neighbor, whose husband was hospitalized due to injuries sustained during the settlers’ attack, to sleep over with her daughter. All the women and girls, 15 in all, with the youngest just 4, slept together in a big room.

At 2:30 A.M., the soldiers returned. “We heard loud banging on the door. I got up to turn on the light but didn’t manage to do so before the door was opened,” Leila Abu Younis says. “The soldiers told us to go outside in the cold and sit on the ground with our hands on our heads. They went into the room and I heard them breaking everything.”

Locals estimate that over 100 soldiers arrived in the overnight operation in the village. They divided into teams of five to seven and, equipped with sledgehammers, went through houses destroying property and food.

In the room where Leila Abu Younis slept with the women and girls, the soldiers uprooted a fireplace, brought down a wardrobe and took the trouble to scatter ashes from the fireplace on clothes and blankets. In the closet, the soldiers found 300 shekels ($82) and 100 Jordanian dinars ($141).

According to people there, the soldiers tore up the money and threw the scraps onto the floor. In a cave next door that is used to store food, they spilled out dozens of kilograms of flour, sugar, salt, rice, olive oil, fermented butter, sheep fat and buttermilk; they also threw blankets over the spilled food.

In addition, they broke the windows at the fodder storehouse, tore up sacks of barley and spilled it out. Someone also opened the sheep pen, releasing the lambs. “I went over to the soldier to tell him that those lambs were ours, but he pointed his gun at me and told me to keep away,” one person says, adding that five lambs had fled or were stolen or run over.

In other homes they broke TVs, cameras, tablets used by children for school, refrigerators. One resident says an officer told him the rationale of the operation: “Yesterday you believed you were strong; today we’ll show you who’s strong.”

Another neighbor says he identified one of the soldiers as a settler who lives nearby. “He approached my nephew, looked him in the eye and told him, ‘You’re forbidden to go out with the sheep again,'” the neighbor says.

Almost every resident who was in the village during the operation, which went on until the morning, recalls the terror. “There was a crib with a 4-month-old baby,” says Tharwat Mehmed, a local resident. “One soldier asked me what I had there; I told him it was a baby, my granddaughter, and then he shouted so he would scare her. My daughter, 19, began to shake with fear. Her face went yellow.”

According to Mahmoud Ahmed, “Five soldiers came into our home. They took all the cheese and all the sacks and spilled everything onto the floor. They threw down all the kitchen utensils and the wheat and mixed it up with sheep medicine.

“I also have a place for pesticides and fertilizers; they spilled those onto the sheep’s barley, ruining it. I was outside with my son, who’s 5 months old, and they didn’t even let me go inside to take a piece of clothing to cover up the child.”

By morning, the soldiers left the village, leaving the people no time to eat the last suhur meal before the last day of Ramadan.

The IDF Spokesperson’s Unit said that the operation Friday night was “a planned operation to locate arms” and that the brigade commander would investigate whether there had been a “breach of regulations.”

But the people of Jinba don’t see the incident as a military operation but as another phase of abuse by residents of nearby settler outposts. Among the soldiers, they identified settlers they know from the area and previous attacks, though now they were wearing army uniforms and carrying military weapons.

In much of the West Bank, this phenomenon of settlers being drafted into regional defense battalions and abusing their neighbors under the guise of the Israeli army has become commonplace during the war. Around 5,500 settlers have been drafted by these battalions, with Masafer Yatta serving as a microcosm.

Saturday was the first day of Eid al-Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan. Women from Jinba said that, for the first time in as long as they could remember, none of them prepared ma’amouls, the traditional holiday cookies.

One of the men took the trouble to buy flour, sugar and other ingredients to make the cookies, but none of the women felt there was any reason to celebrate this year.

“There is great fear in living here,” one of them said. “Our children tell us they don’t want this life anymore, but we’re not giving up.

This article is reproduced in its entirety