A grim poll showed most Jewish Israelis support expelling Gazans. It’s brutal – and it’s true

Right wing demonstrators in Jerusalem in February 2025 calling for the expulsion of Palestinians and building Jewish settlements in Gaza. The placards read ‘Occupation, expulsion, settlement’ and ‘Only transfer will bring peace’

Dahlia Scheindlin writes in Haaretz on 3 June 2025:

In 2014, when Jewish Israelis kidnapped and immolated Mohammed Abu Khdeir, a Palestinian teenager from East Jerusalem, many Israelis were shocked and ashamed. The next year, Jewish Israelis torched a home in the Palestinian village of Duma, burning a father, mother and baby to death in their sleep; a surviving child was horribly burned. By then, few were surprised.

Every so often something forces Israelis to confront the terrible things their society has done. This can happen anywhere. The Israeli historian Elazar Barkan wrote a whole comparative study about how countries acknowledge their historic guilt. But it’s ironic that in the midst of the most brutal action Israel has ever perpetrated, it was a public opinion survey that sparked such a reckoning.

The survey conducted by Professor Tamir Sorek of Pennsylvania State University, published here in Haaretz together with Professor Shay Hazkani, examined what the authors called “eliminatory” attitudes among Jewish Israelis and their theological roots.

Within days I began receiving anguished inquiries about the results. Friends, colleagues, peace activists, journalists and strangers wrote in from Australia to Uruguay to down the block, asking if it could possibly be true that 82 percent of Israeli Jews support “the transfer (expulsion) of residents of the Gaza Strip to other countries?” No less than 54 percent of Jewish respondents were “very” supportive.

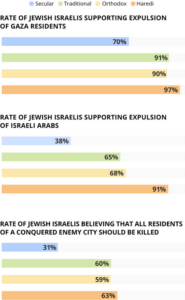

Other findings were grim: A majority of 56 percent of Jews supported the “transfer (forced expulsion) of Arab citizens of Israel to other countries.” And when asked directly whether they agreed with the position that the IDF, “when conquering an enemy city, should act in a manner similar to the way the Israelites acted when they conquered Jericho under the leadership of Joshua, namely, to kill all its inhabitants?” nearly half, 47 percent, agreed.

The survey found a strong correlation between various indicators of religious identity and observance, and militant attitudes – a classic pattern in Israeli Jewish public opinion. But there was strikingly high support from secular Israelis for the expulsion questions too.

People wrote in asking whether the survey’s methodology was credible, or whether the findings sounded remotely reasonable, in my long experience testing conflict-related attitudes. The blunt answer is yes and yes. But the survey does raise questions about the contribution of polls like these to the quality of our public debate – and that’s a hard one to answer.

People wrote in asking whether the survey’s methodology was credible, or whether the findings sounded remotely reasonable, in my long experience testing conflict-related attitudes. The blunt answer is yes and yes. But the survey does raise questions about the contribution of polls like these to the quality of our public debate – and that’s a hard one to answer.

Methodology: no refuge

To assess the poll’s credibility, I contacted Sorek, whom I’ve never met. He generously shared all the raw data, showing the sample distribution, full questions and all responses, and patiently answered all my questions about his methodological decisions regarding the sample design and analysis.

Having seen the numbers, it’s just as faithful a representation of Israeli Jewish society as most other public surveys from media and think tanks, with a relatively large sample of over 1,000 respondents and standard “weighting” methodology to ensure that the critical demographics, like age and levels of religious observance, match what we know about Jewish Israelis from the Central Bureau of Statistics, along with relatively close representation of political groups based on how people reported voting in the last elections. The data was collected by Geocartography, a veteran polling agency whose reputation depends on providing quality data; the weighting process helps correct for groups that are regularly under-represented in internet samples (groups that often lean right-wing, like the ultra-Orthodox).

But even if you make somewhat different sampling or weighting choices, generating small shifts, say five or even ten points, in the data – a finding of 82 percent support for expulsion is so decisive that the big insight remains.

No sample can claim perfection, but there is nothing strikingly wrong here, and the findings can’t be dismissed on technical grounds.

Context and comparison

Are the findings really such an anomaly? What do other surveys tell us? Ron Gerlitz, the Executive Director of aChord, an institute affiliated with Hebrew University of Jerusalem which has conducted regular tracking surveys both before and after the war, wrote a public response in a Facebook post showing that aChord’s findings and several other surveys found lower rates of support on questions testing similar themes of expelling Palestinians from Gaza.

But he too noted that a majority of Jewish Israelis agreed with aChord’s related question about the Trump plan for Gaza, involving “forced emigration, transfer or expulsion by force.” Gerlitz pointed out that 60 percent who agreed was far lower than Sorek’s 82 percent; but this is in large part because aChord offered a “neutral” option, and 26 percent of Jews took it. By contrast, Sorek used what is known as a “forced choice,” meaning there was no neutral option, and people had to make a choice.

Forcing a choice is a legitimate method for getting at people’s inclinations, even if some respondents aren’t sure. Those uncertain respondents could have drifted to the opposition side if they’d wanted to; instead, it looks like most of aChord’s “neutral” respondents gravitated to the “support” side in Sorek’s study (though, of course, these aren’t the same respondents).

Other studies showed similar overall trends. In a poll for Channel 13 in early February, almost immediately after U.S. President Donald Trump announced his plan for Gaza, 72 percent of Israelis supported the plan “to exile Palestinians” – the wording used in the announcer’s description of the poll. That’s a national average; among Jews, it would be close to Sorek’s 82 percent (since very low support from Arab citizens on all related questions drives down the total average). A Channel 12 survey found 69 percent supported the plan, with similar wording about removing Gazans. Once again, although not published, the Jewish portion of those samples would likely have been around the 80 percent mark.

The Peace Index survey from Tel Aviv University from March found that 62 percent of Israeli Jews supported “evacuating Palestinians from Gaza, even by force and military means.” Nine percent of Jewish respondents said “don’t know,” but 70 percent of Jews said that if Gazans leave, Israel should not allow their return at all.

Going further back to 2016, Pew Research, one of the world’s most prestigious polling institutes, asked whether Israeli Jews agree or disagree that “Arabs should be expelled or transferred from Israel.” Nearly half, 48 percent, agreed and the poll made headlines at the time. As noted, a similar question in Sorek’s current study found 56 percent support among Jews – an eight-point rise. Given the spirit of anti-Arab incitement in Israel over the last nine years and the war itself, such a rise makes sense and boosts the contextual credibility of Sorek’s poll.

And remember that by contrast to Arab citizens in Israel, Israelis have come to view Palestinians in Gaza as synonymous with Hamas, Hamas as synonymous with October 7, and both of them synonymous with Nazis.

Finally, it’s worth noting some greater nuance than the big headline in Sorek’s own survey. For example, when asked how the IDF should behave in cities that it conquers, only a minority (18 percent) said there should be “no moral constraints,” and a majority of 55 percent said the IDF should act according to the two most moderate opinions offered: Nearly 30 percent said the IDF should make every effort to protect civilians, and another 26 percent said that civilian harm should be kept to the minimum needed to ensure security. The remainder, about 25 percent, said Israel should use “a tough hand” to ensure security in those situations.

On the worst question of all – “Do you support or oppose the claim that the IDF, when conquering an enemy city, should act similarly to the sons of Israel when they conquered Jericho, by killing all the residents?” – the data cited in Haaretz shows that an unconscionable majority of observant Jews support it. And to my mind, any is too many – but the total of 47 percent shows that supporters, still represent a minority. Again, it’s far too many to be complacent.

Right-wing Israeli activists hold banners that say ‘Only transfer will bring peace’ at a demonstration in Jerusalem in February 2025

First, do no harm

The grave findings prompt the question of whether releasing such findings into an atmosphere already filled with toxic warmongering is helpful or damaging. A responsible public opinion researcher should question whether data can catalyze constructive change, or if it just fans flames.

Both are possible. Salacious data findings that have little public relevance and don’t reflect serious policy options can be more damaging (or self-serving, for headlines) than helpful.

But that’s not the case here. Hardly a day goes by without an Israeli official advocating openly, forcefully and hatefully to expel Palestinians from Gaza. Linguistic hogwash such as “emigration by choice” is pointless; we all know what they mean, and public support for policies is often positively correlated with people’s belief that such plans are likely or possible.

The poll is a messenger, not a provocateur; the findings are an emergency wake-up call that things can still get much worse. A population subject to years of anti-Palestinian incitement felt that Hamas’ attack on October 7 proved the worst and justifies everything Israel has done since – another over-80 percent finding among Jews in the joint Israeli-Palestinian survey from July 2024, mirrored on the Palestinian side. Rapacious, corrupt leaders capitalized on Israeli suffering instead of seeking to contain the rage. It was this kind of leadership-driven extremist nationalist fervor stoking existing nationalist racism within the Serbian public during the breakup of Yugoslavia that degenerated into genocidal acts against Bosnian Muslims.

But when wars end, when criminal leaders are jettisoned from power, new leaders can drive change. The worst regimes and the worst wars in recent history – be grateful that I’m not naming names – have transformed into some of the most peaceful, thriving, cooperative and productive countries in the world.

The time for leadership by brave people of vision and values is now. The candidates displaying such qualities are pitifully few.

This article is reproduced in its entirety