A critique of Palestinian BDS

Photo taken in South Africa in the 1950s shows supporters of the African National Congress (ANC) gathering as part of a civil disobedience campaign to protest the apartheid regime of racial segregation. By the 1950s the ANC, with Christians and Jews forming the established leadership of protest movements which could mobilise the masses – despite tribal divisions which were once thought to be insuperable. Photo by AFP/Getty Images

Sanctioning Apartheid: Comparing the South African and Palestinian Campaigns for Boycotts, Disinvestment and Sanctions

Forthcoming in David Feldman (ed.) Boycotts: Past and Present (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). Thanks to the author for permission to reproduce it here.

By Lee Jones

By Lee Jones

Senior Lecturer in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London.

January 2016

Introduction*

In 2005, Palestinian civil society activists called for boycotts, disinvestment and sanctions (BDS) against Israel, stating they were ‘inspired by the struggle of South Africans against apartheid’. Indeed, the South African experience and analogy is central to their campaign. First, it provides a framework for a moral critique of Israel: it is framed as an ‘apartheid state’, creating an imperative for the world to support Palestinians as they had black South Africans, in the name of ‘moral consistency’. Secondly, the South African anti-apartheid movement’s (AAM) use of BDS provides a new strategy to fight Israeli oppression following the failure of other approaches, including armed struggle and the Oslo peace process. Prominent Palestinian activists thus see BDS as ‘the South Africa strategy for Palestine’.

Framing current struggles using historical analogies is a well-worn practice. Marx, in the 18th Brumaire, observing the 1848 Paris Commune, noted that revolutionaries ‘anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language’. Khong (1992) found that US foreign policymakers repeatedly invoked the Munich debacle to justify militarily confronting, rather than ‘appeasing’ communism during the Cold War. And many other advocates of international sanctions have used the South Africa analogy. US Senator Mitch McConnell, for example, justified sanctions against Myanmar (Burma) by claiming that ‘sanctions worked in South Africa, and they will in Burma too’, while Archbishop Desmond Tutu branded Myanmar the ‘South Africa of Southeast Asia’, urging the world to ‘do for Burma what it did for South Africa’ . The Free Burma Campaign explicitly sought to ‘recreate what went on during the AAM’, employing its methods and even its now-redundant activists.

Such framing, while potentially useful, carries significant risks. Marx argued that the ‘awakening of the dead’ from earlier revolutions was justified only insofar as it ‘served the purpose of glorifying the new struggles, not of parodying the old; of magnifying the given task in the imagination, not recoiling from its solution in reality; of finding once more the spirit of revolution, not making its ghost walk again.’ As this implies, historical analogies can distract revolutionaries from contemporary realities and priorities, preventing genuine progress. This, Marx argued, was the case in the upheavals of 1848-1851, when, ‘only the ghost of the old revolution circulated’.

This chapter argues that this is also true of the BDS movement’s use of the South African analogy, where easy rhetoric distracts from the hard task of meaningful strategising and popular mobilisation. The campaign’s claim that ‘Palestine’s South Africa moment has finally arrived’ (Omar Barghouti, 2013) masks critical differences between these two cases. Crucially, in South Africa, BDS was a supplementary tool used by a powerful, strategically-led and mass-mobilised liberation struggle. In Palestine, BDS is partly intended to create such a movement, following the liberation struggle’s stark decline. This asks too much of BDS: it did not serve this function in South Africa, and its prospects for doing so in contemporary Israel/Palestine are weak. Furthermore, the absence of mass struggle in Palestine makes it unlikely that BDS will be effective; it was only the presence of such struggle that allowed BDS to ‘bite’ in South Africa and precluded their costs being deflected onto oppressed groups. Finally, lacking the ANC’s clarity on goals and strategy, the Palestinian BDS campaign is politically incoherent. It lacks consensus on the end goals, and the mechanisms by which BDS is meant to contribute to their achievement; consequently, it neither focuses on activating these mechanisms, nor does it evaluate ‘success’ sensibly.

My purpose in highlighting these problems is not to dismiss the BDS campaign or the Palestinians’ plight. Rather, it is to stimulate critical, sympathetic reflection on political strategies for those seeking liberation. As Marx argued, a genuinely radical movement ‘cannot take its poetry from the past but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped away all superstition about the past’. Its agents must constantly criticise themselves, constantly interrupt themselves in their own course, return to the apparently accomplished, in order to begin anew; they deride with cruel thoroughness the half-measures, weaknesses, and paltriness of their first attempts… until a situation is created which makes all turning back impossible.

The chapter is divided into four parts. The first briefly outlines the ANC’s view of BDS. The second highlights the critical difference between the ANC’s use of BDS and the Palestinian movement’s position. The third argues that the absence of Palestinian mass struggle will constrain the efficacy of BDS. The fourth highlights the incoherence of BDS advocates’ tactical perspectives.

The ANC’s View of BDS

The ANC’s perspective on BDS corresponded to its sophisticated analysis of South African society and its associated strategy to hasten apartheid’s demise. This analysis was grounded in a Marxist reading of South Africa’s political economy and the social forces underpinning the apartheid regime. Based on this, the ANC adopted a revolutionary strategy based on ‘four pillars’: mass struggle; underground organisation; armed resistance; and international solidarity. BDS measures formed part of the fourth ‘pillar’, and were always seen as supplemental to the primary ‘pillar’, mass mobilisation. BDS were intended to help alter the balance of forces struggling for power in South Africa: to fragment the ruling bloc, prompting defections from the apartheid coalition, and to boost the position of anti-apartheid forces, thereby forcing the regime to negotiate a transition to democracy. Mass struggle was absolutely essential in enabling sanctions to have this effect.

Joe Slovo, white Jewish leader of the South African Communist Party and leading member of the ANC. He was a critic of Israel’s policies, highlighting the cooperation between Israel’s administrations and apartheid-era South Africa and noting the irony of a nation of dispossessed refugees establishing a state founded on the idea of exclusion.

from History of South Africa (Part 2) Image, South African Communist Party

The ANC’s analysis of apartheid was shaped by its longstanding alliance with the South African Communist Party. The ANC viewed apartheid as functional for a ‘colonial’ form of capitalist development, and saw the regime as rooted in a coalition of class forces benefiting from this arrangement. Following classical Marxist theories of revolution, they argued that regime change would occur when this ruling coalition – English and Afrikaner capitalists, the white middle and working classes, and subordinate, non-white elites running the Bantustans and other apartheid institutions – was overwhelmed by mass non-white opposition, through civil disobedience, strikes, military attacks and other measures to render society ‘ungovernable’, compelling the regime to negotiate a transition to multiracial democracy. The ANC’s 1955 Freedom Charter clearly specified democratic-socialist end goals, which were adopted by most anti-apartheid forces, including the trade unions and the United Democratic Front (UDF).

BDS fits coherently into this overall strategy. They were seen as useful in ‘restraining the regime’s capacity [to suppress opposition], dividing the alliance of forces behind the apartheid state, [and] uniting and broadening the anti-apartheid support base’ (Maharaj, 2011). The first two – destructive – mechanisms were particularly emphasised, as a means to help weaken the ruling coalition vis-à-vis the rising power of the mass opposition constructed by the other ‘pillars’. ANC President Oliver Tambo argued that external flows of trade, investment, technology and military cooperation bolstered the state’s capacity to repress opposition; severing these flows via sanctions would ‘weaken the system and making it less capable of resisting our struggle’ (Starnberger Institute, 1989). Thabo Mbeki argued that undermining white prosperity would support the ‘breaking up of the power structure… out of this you will get a realignment of forces’. In particular, since the ANC’s Marxist analysis indicated that big business exerted predominant influence over the state, ‘the real target’, a senior trade union leader states, ‘was internal capital’. Harming its interests would encourage it to defect from the ruling coalition, engage in ‘civil disobedience’ and ‘put pressure on’ the regime. Sanctions were thus ‘designed to turn as many significant forces within this society as possible against apartheid policy’ (Erwin, 2011). BDS played only a minor role in constituting the rising mass opposition that would exploit this growing regime weakness. The campaign for BDS, being nonviolent, successfully included groups like churches that were squeamish about other ANC tactics ( Boesak, 2011). However, it was the campaign itself, not the effects of actual BDS measures, that had this mild effect, and the primary factor mobilising opposition was obviously apartheid rule itself.

By the 1980s, the targets the AAM sought for BDS reflected this overall strategy. The AAM’s initial boycott campaigns, launched in 1960, did not: they focused on symbolic South African products like fruit, and sporting and cultural boycotts. ANC strategists did not expect these measures to coerce pro-apartheid forces; they were instead intended to mobilise Western publics, to build support for more meaningful sanctions later on, which would harm key groups inside South Africa (Maharaj, 2011). Consequently, despite grossly exaggerated claims about the sports boycotts’ efficacy, the primary means by which BDS was intended to work was material not, as liberals often suggest, psychological. As a contemporary analyst argued: ‘sanctions are not intended primarily to influence the subjective intentions of the existing power holders… Rather, they are seen as contributing, in conjunction with other forms of struggle, towards creating objective conditions in which… a transfer of power is placed on the agenda’ . Thus, in the 1980s, as internal opposition mounted, the ANC advocated sanctions that would inflict maximal damage on South Africa’s economy, hoping to damage large-scale business interests perceived as central to the ruling bloc.

Crucially, BDS were only ever a supplement to the primary ‘pillar’ of ANC strategy: mass mobilisation. ANC leaders repeatedly emphasised that BDS alone ‘will not bring results’ (Lodge, 1988). As the AAM’s Abdul Minty stated: ‘victory will come through the struggle of the people… sanctions must be regarded as a complement to that struggle and not as an alternative’.

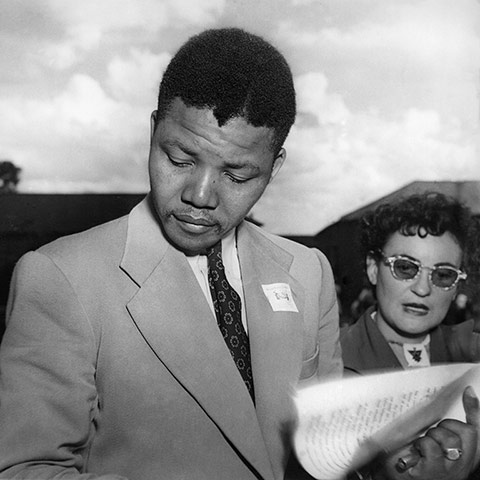

Nelson Mandela and Ruth First, both then in the Communist Party. This experience directly influenced their analysis of South Africa.

The ANC’s political analysis told them that, given that objectionable regimes are always underpinned by powerful societal interests, they cannot be ‘persuaded’ to change, including by sanctions; they had to be forced to do so by mass struggle – the force that always made history. This analysis was substantially borne out since, without mass struggle, BDS failed to compel political changes. Sanctions were imposed on South Africa at several junctures, including oil embargoes from the 1960s and an arms embargo in 1977. However, the regime evaded these by creating import-substituting oil-from-coal and armaments industries, which enriched many loyal businesses and individuals. The exorbitant cost – over $50bn – was borne as the price of white domination, and was affordable so long as the non-white labour that generated South Africa’s wealth remained quiescent. Because sanctions were imposed following defeats of the internal opposition (the 1960 Sharpeville massacre and the 1976 Soweto uprising), the regime was able to deflect their costs onto the oppressed population.

The regime was only prevented from repeating this strategy when mass resistance made it impossible to do so. By the mid-1980s, black urban unrest was so intense and sustained that the regime could no longer repress it by force. A crucial aspect here was the strategic centrality of the black working class: while the UDF was temporarily neutralised by police crackdowns, the regime could not quash the unions without crippling the economy; consequently labour militancy actually rose. Accordingly, the regime was forced to try to undercut the rebellion by increasing spending on township housing and services. However, as the then finance minister recalls, because sanctions – in combination with a deep structural economic crisis unrelated to BDS – constrained the overall resources available, the regime struggled to finance sanctions busting, coercion and welfare simultaneously. Consequently, the government ‘saw a revolutionary type of situation developing, where we would not [even] have been able to deal with conflict control’. Without mass mobilisation, this dilemma would simply not have existed. Mass struggle also disabled the regime’s attempt to draw non-white elites into neo-apartheid political structures: Bantustan governments, coloured and Indian legislatures and black local authorities. Rent and service-charge payment strikes, street protests and attacks on collaborators paralysed these institutions, causing this strategy of co-option to fail. The white ruling elite was thus confronted by a choice between spiralling unrest or a negotiated settlement. Powerful and wealthy groups increasingly realised that their interests could no longer be served by apartheid, and began calling for negotiations.

In South Africa, then, BDS were part of a coherent strategy aimed at clearly defined goals. They were expected to modestly assist the overall strategy of fragmenting the ruling power bloc, which, in combination with rising mass opposition, would compel the regime to negotiate a settlement. Crucially, their destructive effects on the ruling coalition occurred only in the presence of mass struggle.

Critical Differences: The Weakness of the Palestinian Liberation Movement

While in South Africa BDS contributed to a mass liberation struggle, for pro-Palestinian activists, BDS is seen as a means to construct such a movement. Here, there is no burgeoning, strategically-led, mass-mobilised movement seeking an additional means to coerce its enemies, but a legacy of defeat, fragmentation and despair. BDS activists lack clear goals, hoping instead that their campaign might generate political consensus and revive collective struggle. There is no analysis of power relations in Israel/Palestine, nor any strategy for shifting these into which BDS fits; BDS is simply grasped at because ‘nothing else has worked’.

Accordingly, the suggested mechanisms through which BDS might ‘work’ are often contradictory or lifted unreflectively from the South African experience, without asking whether they can be reolicated in Israel/Palestine – as they typically are not. This strategic incoherence leads activists to confuse means and ends, making spurious claims of ‘success’ despite negligible results on the ground.

(a) The Weakness of the Palestinian Liberation Movement

While it is rarely stated explicitly, the 2005 BDS Call was clearly a response to the dramatic decline of the Palestinian struggle for national self-determination. The PLO was once in the vanguard of a worldwide anti-imperialist movement, modelling itself on the Vietnamese struggle and receiving extensive transnational support. However, following the defeat of progressive forces in Arab states and later elsewhere, the PLO was cut adrift and fell into decay. Although hopes were raised by the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords, many Palestinians now view the ‘peace process’, said Edward Said in The End of the Peace Process as a sham that co-opted their leaders and demobilised the national liberation struggle.

Through the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), ‘a small clique of leaders who were mostly detached from the struggling Palestinians on the ground hijacked… decision-making power’ (Ramzy Baroud, 2013). The PNA’s circumscribed mandate left it ‘inherently incapable of supporting any effective resistance strategy… Indeed… the P[N]A’s role has actually been detrimental’ (Barghouti, 2011). As a de facto gendarme of the Israeli state, the Authority assumed the worst aspects of authoritarian Arab regimes, demobilising the masses and repressing dissent, often violently.

The PNA became absorbed with municipal administration, devoting its energies to state-led ‘development’, backed by the international financial institutions, which created vested interests in the status quo that further undermined political resistance. The Authority became ‘a kind of mafia’, dispensing monopolies, contracts and special deals to build patronage networks (Said, 2002). These measures, including joint ventures with Israeli firms, led to the ‘systematic… corruption and co-optation of a whole class of Palestinian politicians, businessmen and intellectuals, [such that] the Palestinian culture of resistance and heritage of struggle has been distorted and undermined’ (Barghouti, 2013). By 2002, the Authority’s bloated bureaucracy employed around 140,000 people, making up to one million Palestinians indirectly dependent on PNA patronage and thus unlikely to challenge its authority (Said, 2002). Others formed numerous NGOs, dependent on foreign funding and constrained to pursue only technocratic agendas, thereby ‘mirroring [the loss of credibility] experienced by the political leadership’. Thereby, as Omar Barghouti observes, many ‘sectors of Palestinian society have become so dependent upon interim arrangements and foreign aid… as to put paid to the possibility their contributing to the fight for real change’.

By the early 2000s, then, the Palestinian resistance was in ruins. As Edward Said complained,

under the PNA’s large, corrupt, bureaucratic and repressive apparatus… people are cowed into silence and apathy… [they] seem to have given up all hope and all will to resist the extraordinary disasters visited on them by their leadership, which cares not a wit for anything except its own survival… [it] has simply abandoned them… We are an unmobilised people. We are unled. We are unmotivated… It is as if we have been anaesthetised as a people, unable to move, unable to act.

The situation worsened after Said’s death, with the Fatah-Hamas split. As a former PLO official lamented:

every institution or overarching structure that once united Palestinians has now crumbled and been swept away… no single body [is] able to claim legitimately to represent all Palestinians; no body able to set out a collective policy or national programme of liberation. There is no plan… we are at a nadir in our history of resistance

(Nabulsi, 2010).

Accordingly, the contemporary BDS campaign is not intended to bolster a powerful, well-led and mobilised liberation struggle, as in 1980s South Africa, but rather to try to bring such a struggle into being. This is explicit in BDS activists’ discussions. Said himself stumbled from growing despair at the PNA’s degradation into calling for an international BDS campaign as a means of ‘reactivat[ing] o[ur] will’ and ‘mobilis[ing] ourselves and our friends’. Similarly, campaigners state that the BDS Call was needed merely to ‘affirm that our national liberation movement is still alive’, and to ‘revive our culture of collective activism’ (Barghouthi, 2012). They deliberately adopted very minimalist goals as a ‘basis… to campaign upon and a means to limit sectarianism’ for ‘organisations unable to present a stronger platform’, hoping to ‘recreate the sense of unity and purpose’ lost since the 1980s. BDS would, Barghouti hoped, serve as a ‘political catalyst and moral anchor for a strengthened, reinvigorated international social movement’.

Understandable and necessary as these goals are, the BDS Call is unlikely to help achieve them. Despite deliberately appealing to the lowest common denominator, its extremely thin platform still does not command universal support. The BDS Call specifies three demands:

(1) an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories and the dismantling of the West Bank Barrier; (2) recognition of the rights of Arab citizens of Israel to full equality; (3) respect for Palestinian refugees’ right to return.

Beyond this, unlike the ANC’s detailed Freedom Charter, the movement eschews substantive goals and programmes. As Barghouti notes: ‘individual BDS activists and advocates may support diverse political solutions’ and accordingly the ‘movement… does not adopt any specific political formula’. The BDS Call thus expresses rather than surmounts Palestinians’ disorganisation and division, compelling the movement to avoid any commitment to clear political goals. Although one might argue that this is merely a starting point to rebuild consensus, in practice, even this minimalist platform has failed to unify Palestinians. Several NGOs opposed BDS as a ‘blow to the P[N]A and a subversion of the strategic direction of the Palestinian national movement’. The comprador Palestinian business elite opposes BDS. So did the PNA for five years, before timidly endorsing only a minimal boycott of products from illegal Israeli settlements. Thus, BDS does not appear to be facilitating political reunification.

Pretoria, South Africa: Banner-bearing women demonstrate outside The Pretoria Supreme Court after Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment. June 12, 1964. Women were active in the resistance to pass laws and could be called upon by the ANC’s Women’s League. White anti-apartheid women organised in the Black Sash.©TopFoto / The Image Works

Nor is it clear how BDS can revive collective activism. Some BDS advocates apparently recognise that ‘the “South African treatment” [involves] global boycotts from outside supporting mass struggle inside. Yet they do not explain how this mass struggle is to be produced. BDS did not create this struggle in South Africa; ANC leaders explicitly denied that sanctions were required to spur the masses into action, insisting they would only supplement an already-mobilised mass movement.

The key dynamics enabling this were the emergence by the 1980s of a well-organised black working class, whose labour was essential to South African capitalism, and of Charterist civic organisations through decades of grassroots organising. Despite the South Africa analogies, contemporary conditions in Israel/Palestine are markedly different. The Palestinian working class is poorly organised and led, and entirely lacks a strategic position in the Israeli economy. Although Israeli capitalism became dependent on Palestinian labour after 1967, following the First Intifada, 1987, Israeli businesses deliberately reduced their Palestinian workforces, turning instead to migrant workers and new Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet bloc. Accordingly, economic dependency has been reversed: Palestinians now rely on Israeli firms to provide them with livelihoods , even being compelled to help build illegal Israeli settlements. As for civic organisations, while the BDS Call may provide a platform for some to collaborate, unlike UDF groups, many NGOs are beholden to foreign donors and the PNA, constraining their political freedom. It is not clear how BDS can transform this structural constraint.

Opposition to ANC

Robert Sobukwe, founder and leader of the Pan Africanist Congress. He was an Africanist and did not want to work with non-Africans. “We aim, politically, at government of the Africans by the Africans, for the Africans, with everybody who owes his only loyalty to Africa and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as an African.

Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Inkatha party. Although he opposed apartheid, the fact that his party was rooted in the Zulu homeland made him very acceptable to the South African government which at that time had a policy of sending all black Africans to Bantustans, or mythical homelands.

Moreover, BDS are generally better at creating division than unity. Notwithstanding the simplistic myths peddled about South Africa by BDS campaigners, sanctions were extremely divisive there, being opposed by the anti-apartheid white opposition party, some non-white unions, and non-ANC black leaders like the Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who all argued that they harmed non-whites and provoked white intransigence. It took active political mobilisation to win the majority over to the ANC/UDF position, including a violent struggle against Buthelezi’s Inkatha organisation. Similarly, in the 1990s, Iraqi opposition groups initially rallied around sanctions, but this unity dissolved as soon as sanctions began to bite, causing fatal divisions. In Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi’s call for sanctions alienated middle class urbanites, unemployed workers, other opposition parties, and ethnic-minority groups desperate for economic development.

Given the Palestinian opposition’s parlous state, if an analogy must be drawn to South Africa it should be to the 1960s, not the 1980s. In 1960, rising social unrest was quashed by the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC was banned and its leaders jailed or exiled. Serious mass resistance did not resurface until 1976, when it was again suppressed by force. Sanctions, imposed after each crackdown, did not ‘bite’ until sustained mass unrest re-emerged in the mid-1980s, alongside a profound economic crisis. Palestine remains very far indeed from this scenario.

(b) Contradictions and Incoherence in Goals and Tactics

Reflecting the overall lack of political direction, the BDS campaign exhibits significant confusion over its goals and methods.

Disagreement over the goals of BDS is fundamental. As already noted, given severe intra-Palestinian divisions, BDS campaigners cannot specify even the bare outlines of a political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Thus, while Barghouti claims that most BDS advocates support a two-state solution, Erakat suggested (2012) that the BDS call is ‘an implicit endorsement of the one-state solution’ – possibly because a two-state outcome is perceived as incompatible with the movement’s goal of a right of return for all Palestinian refugees. In any case, without a collective political vision, it is difficult to build a substantive consensus, or to make or measure progress towards its realisation.

What effect do you hope that refusing to buy these products will have on the occupation

Accordingly, there is also considerable confusion over the mechanisms by which BDS is meant to contribute to Palestinians’ struggle. Writing on South Africa, Crawford and Klotz suggest four basic mechanisms by which sanctions might ‘work’:

(1) ‘Compellance’: BDS increases the cost of objectionable policies to exceed their benefits, causing leaders to change their policies.

(2) ‘Normative communication’: BDS signals moral condemnation, ‘persuading’ leaders to change their policies.

(3) ‘Resource denial’: BDS denies the target state the resources required to sustain its objectionable policies.

(4) ‘Political fracture’: BDS stimulates a domestic legitimacy crisis, leading to a change of government and thereby political change.

As noted above, the ANC saw sanctions working primarily through ‘political fracture’. The ‘resource denial’ and ‘compellance’ mechanisms were only co-constituted by ‘political fracture’, since the costs of maintaining apartheid were affordable until mass unrest created new demands on state finances; consequently, these mechanisms did not work independently of mass mobilisation. The ANC had little faith in ‘normative communication’, rightly believing that oppressive regimes cannot be ‘persuaded’ to relinquish power but must be forced to do so.

Unlike the ANC, Palestinian BDS campaigners lack a coherent analysis of social power relations in Israel and a strategy for shifting these, in which BDS might figure. Instead, they grasp at diverse and contradictory possibilities through which BDS might help, implicitly invoking several of Crawford and Klotz’s suggested mechanisms. Many propose that BDS may be useful in ‘raising awareness’ of Palestinians’ plight, harming Israel’s ‘image’ and diminishing its legitimacy – i.e., ‘normative communication’. Exactly how this will generate political change, however, is never specified. As Richard Falk observed, ‘winning the “legitimacy war” may not be enough. It has not been enough, for instance, to emancipate the people of Tibet or Chechnya’. Even in the far more favourable historical conditions of the mid-1970s, ‘the PLO could point to a range of international supporters… but it was no closer to its goal of creating a Palestinian homeland’ (Chamberlin, 2012).

To make strategic sense, one must specify a plausible sequence of events whereby delegitimising Israeli behaviour through BDS produces some other change which, in turn, leads to concrete changes in political outcomes. For example, the goal could be, as with early South African boycotts, to build Western public support for the withdrawal of US aid or more meaningful sanctions that would materially diminish Israel’s repressive capabilities, or foster domestic political realignments (as glancingly implied in US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation, 2010. On this view, the initial target of ‘normative communication’ is not actually Israel, but rather Western publics and governments, with a view to enabling later sanctions that would be aimed at Israel, to produce ‘resource denial’ or ‘political fracture’.

However, not only is this two-stage strategy not articulated, other activists openly reject the idea of an intermediate step, pursuing BDS to create direct change in Israel/ Palestine. Moreover, this group is also divided over how this might work. One group favours ‘normative communication’, suggesting that BDS ‘relies on persuasion’, seeks to ‘convince Israel of its moral degradation and ethical isolation’, and promotes ‘re-education in Israel’. More common, however, is an ANC-esque perspective that ‘the basic logic of BDS is the logic of pressure – not diplomacy, persuasion, or dialogue’.

Yet, exactly how this ‘pressure’ can generate change is again not clearly specified. Some imply a ‘compellance’ logic, suggesting that BDS should ‘raise the cost of the occupation’. The problem with ‘compellance’, however, is that sanctioned governments are frequently willing to absorb massive economic costs to pursued cherished political ends – over $50bn in South Africa, for instance. The Israeli occupation’s cost is already increasing without sanctions: after yielding net profits from 1967 to 1987, it now costs an estimated $9bn yearly, of which military costs ($6bn) are rising by 7 percent annually. Yet, there is no prospect of the occupation ending. The key challenge, then, is not to raise Israel’s costs, but to prevent Israel continuing to absorb rising costs. In South Africa, this took sustained mass mobilisation. In Palestine, there is no prospect of this.

Protesters hold a banner reading ‘Solidarity with Palestinian people: Boycott Israel’ during a demonstration against Israeli offensive on Gaza, in Madrid. Photo by AFP

Other activists suggest a ‘resource denial’ logic, similar to the second part of the two-step strategy suggested above. Disinvestment, it is suggested, can ‘cut-off the funding used to sustain the occupation’; tourism boycotts can deny Israel ‘vital investments and foreign currency’; academic boycotts can weaken Israeli universities, which supply ‘the ideology and tools of occupation’; and an arms embargo would make Israel ‘unable to continue its war crimes… if it cannot replenish… [its] military arsenals. Whether ‘resource denial’ makes strategic sense ultimately depends on the importance of these external flows in sustaining Israeli dominance. This importance is asserted by many BDS advocates, but never actually demonstrated.

Consider just the suggested arms embargo. Israel has received about $3bn of US aid annually since the 1980s, much of which finances arms imports. However, Israel has also developed a large domestic armaments industry, which exports around three-quarters of its output, yielding $7bn in 2012 (AFP, 2013). Because this industry probably relies heavily on international technical collaboration, components supplies, etc, it would likely suffer if these links were severed. However, the South African experience shows that even embargoed states without an arms industry can develop one and produce sophisticated conventional, chemical and even nuclear weapons. Sanctions never deprived South Africa’s security forces of their coercive capacity; rather, sustained and growing unrest made coercion an impractical means of maintaining long-term social order. Even if Israel’s arms industry suffered relative decline under BDS, the sector’s existence and adaptive capacity makes it extremely unlikely that the Israeli state would be starved of the equipment necessary to repress the Palestinians. And, again, without mass mobilisation, coercion will likely remain a viable option.

A final group of BDS activists invoke ‘political fracture’ logics. Barghouti’s scenario envisages that under BDS pressure, initially Israel’s ‘colonial society bands together’ but later, this unity starts to crack… the natural human quest for normalcy… will lead many… Israelis to withdraw their support for Israeli apartheid and occupation. Many may even join movements that aim to end both. Collapse of the multitiered system of oppression then becomes a matter of time… we’ve seen it all before in South Africa.

Others similarly suggest BDS will ‘catalyse an anti-Zionist movement in Israeli society’, ‘create a critical mass of minority dissidents’ and ‘prompt the Israeli public to reconsider’.

There are two problems here. First, again reflecting the lack of clear strategic thought and leadership, activists disagree over whether Israeli society is really the target of sanctions. As Said had earlier insisted, Warschawski (2012) asserts that ‘the Palestinian national movement needs as many Israeli allies as possible… [consequently] BDS is addressed to the Israeli public’. But Taraki and LeVine flatly assert: ‘the BDS movement does not address the Israeli public directly in order to persuade it or to appeal to its sense of justice’, despite having identified ‘mov[ing] the Israeli body politic’ as ‘the logic of BDS’ just four pages earlier (2012). Similarly, while Falk maintains that ‘Israeli participation is valued highly’ and Pappe (2013) asserts ‘it is vital to keep in touch with the progressive and radical Jewish dissidents’ as a ‘bridge to the wider public in Israel’, Barghouti is openly suspicious of ‘soft Zionists’ and the ‘Zionist left’ hijacking BDS to ‘save Israel’ as an apartheid state. Unsurprisingly, despite the BDS committee’s official invitation to ‘conscientious Israelis to support [their] call’, even sympathetic Israelis perceive that ‘Palestinian society does not welcome Israeli solidarity anymore’ (Alexandrowicz and Vilkomerson, 2012).

A second problem concerns the simplistic South African analogy: it is inaccurate to suggest that BDS spurred the formation of a politically significant anti-apartheid movement among whites. When confronted by sanctions, the historically more liberal English-speaking South Africans typically rallied around the incumbent government. As for Afrikaners, even by the 1980s, psychological researchers found extremely low levels of guilt over their treatment of non-whites (Cohen, 1986). A late-1980s survey of Afrikaner elites found moderate to strong attachment to racist attitudes, hostility to majoritarian democracy, and fear of a ‘communist’ takeover (Manzo and McGowan, 1992). Despite a growing sense of isolation under sanctions, white elites overwhelmingly adopted a defiant attitude to BDS (van Wyck, 1988). A 1989 poll found that, despite widespread falling living standards, only 24 percent of whites favoured negotiations with the ANC and just 2 percent a transfer of power to the black majority, while 59 percent believed those imposing sanctions were making ‘extreme’ demands and favoured making no concessions.

In fact, rather than changing attitudes, popular responses to BDS were filtered through party affiliations, thereby confirming people’s existing beliefs. Whites actually lurched rightwards as sanctions intensified: the Conservative Party increased its vote from 17 to 29 percent from 1981 to 1987, displacing the anti-apartheid Progressive Federal Party as the official parliamentary opposition. Thus, there was no straightforward connection between BDS-induced economic pain and politically progressive changes in white opinion. As mentioned earlier, the really decisive shift was in the orientation of large-scale capital – not the wider public. As the ANC had perceived, big business leaders exercised profound structural influence over the state and played a significant role in lobbying for change and preparing the wider population for a negotiated settlement.

From this perspective, targeting sanctions at particularly powerful social groups could be an important element of BDS strategy. However, reflecting its lack of coherent strategic vision, the Palestinian BDS National Committee has apparently undertaken no sustained analysis of Israeli society that might reveal the key forces and alliances underpinning the regime. The only individual who has apparently begun this vital analysis is the Israeli economist Shir Hever. He identifies large-scale conglomerates as the key linchpin of the Israeli state: it is their ‘taxes [that] fund Israel’s military budget, and the owners… exert extensive political power over the Israeli political sphere’. Consequently, he suggests, BDS should target them to ‘pressure… them to create positive change’, inflicting maximal damage on companies’ markets, investment flows and stock prices, since only a ‘painful impact’ will compel a change of strategy (Hever, 2012).

However, because the BDS movement lacks a centralised leadership and strategy, it is instead left up to individual activists to decide how they think BDS might work and, accordingly, who to target. Barghouti insists that ‘tactics and the choice of BDS targets at the local level must be governed by the context particularities, political conditions, and the readiness in will and capacity of the BDS activists… BDS can be adapted to according to the specific context in each country’. ‘Your preferences’, one campaign tells activists, should dictate the choice of target. A ‘narrow focus’, e.g. on settlement products, is ‘perfectly fine’. But this may simply be false. If the movement adopts the two-stage strategy suggested earlier, then initially focusing on firms in the Occupied Territories which ‘epitomise the most oppressive aspects of the occupation’ (US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation, 2010: 16) may be a good idea, insofar as no significant economic or political consequences within Israel are anticipated at this stage.

However, if the intention is to immediately damage the Israeli economy, this focus is completely pointless. Boycotting such firms targets ‘marginal products… [that] do not contribute substantially to the settlements’ economic sustainability’, and companies that emphatically do not ‘play the most significant role in shoring up Israel’s occupation’ and do not exercise significant political leverage (Hever, 2013). Instead of adapting BDS to the context where activists are located, it would make far more sense to adapt them to the context in Israel/Palestine.

(c) Means-Ends Confusion and Spurious ‘Success’ Claims

Finally, lacking clarity on their campaign’s goals and mechanisms, BDS activists often confuse means and ends, making spurious claims of ‘success’ despite failing to improve Palestinians’ situation.

As some BDS activists recognise, ‘BDS is not a goal in itself. Rather, it is a means by which to pressure the Israeli government’ (Hanna, 2013). Logically, therefore, success should be measured by the practical political effects BDS measures produce on the ground, and how these advance the overall liberation strategy towards a final goal. However, because the campaign lacks both clear end goals and a strategy, this is impossible. Instead, the relationship between ends and means becomes muddled. The US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation, for instance, defines the achievement of BDS measures as the end goal, with BDS campaigns as the means to achieve them. Activists report ‘success’ and ‘achievements’ merely when the volume of boycotts and disinvestment increases. ‘Success’ is implicitly defined circularly: the ‘immediate noteworthy outcomes’ of one cultural boycott are further cultural boycotts (Barghouti 2012).

This may make sense as part of the two-stage strategy hypothesised earlier, but even then we would still want to distinguish and evaluate: (a) the achievement of the initial boycott or disinvestment, (b) whether this generates political support for tougher sanctions; and then, for stage two, (c) the imposition of those sanctions and (d) the consequential impact on the situation in Israel/Palestine. Given the extreme distance between (a) and (d), declaring ‘success!’ at (a) is obviously premature. While this may help boost campaigners’ morale, it is nonetheless essential to maintain a clear means-end distinction, within an overall strategy, with clearly defined goals, to avoid hasty and romantic self-congratulation and to stimulate continual reflection on the efficacy of individual tactics.

This is doubly important because BDS has so far made no appreciable difference to Palestinians’ lived existence, notwithstanding some exaggerated press coverage (The Economist, 2014). Sourani asks: ‘what has been the impact on Israel’s policies and practices? In short, we are living through the worst period in the history of the occupation’. Economically, ‘BDS has not had a significant impact on companies that do not operate directly’ in the Occupied Territories (Hever, 2013). Indeed, ‘the Israeli economy is stronger than ever’. Politically, the Israeli left has been completely ‘marginalised’, with growing ‘public sympathy for police and army violence against protestors’ (Baum and Amir, 2012). Even among those directly targeted by BDS, like academics, ‘not much has changed’. Peace talks, resumed in July 2013, collapsed in May 2014, with almost 70 percent of Israelis backing their government’s decision to walk away (Times of Israel, 2014).

Conclusion

Comparing the Palestinian BDS movement to its chosen analogue, South Africa, reveals several interrelated shortcomings. Unlike the ANC, the BDS movement lacks political leadership, clearly defined political goals, a coherent economic and political analysis of Israel/Palestine, and a strategy for transforming that situation. Instead, Palestinians have grasped at BDS out of desperation, in an effort to reincarnate a meaningful liberation movement. Yet BDS does not appear to have catalysed greater Palestinian unity, nor does it seem realistic to hope that external solidarity can rebuild the Palestinian resistance. Reflecting Palestine’s socio-political divisions, the BDS campaign exhibits strategic incoherence and mutually inconsistent perspectives, generating muddled activist thinking and practices that are disconnected from the actual situation on the ground. The South African analogy distracts activists from confronting and surmounting these realities, permitting the comforting but ultimately delusional fantasy that victory is just around the corner.

This analysis suggests several priorities. First, the most urgent task remains the rejuvenation of the Palestinian liberation movement. It is difficult to imagine any real role for BDS until Palestinians’ divisions, disarray and demobilisation are overcome and the masses are re-engaged in a sustained struggle for their own liberation. Many activists clearly recognise this, but are misled – partly by misrepresentations of the South African case – into thinking that BDS can catalyse this renewal. The South African case suggests that, at best, BDS can supplement an active struggle, not create one. Second, the BDS National Committee must assume a more directive leadership role. Their campaign cannot be effective without a more substantive set of goals and a plausible strategy for achieving them. This will require active political work and extensive analysis of the Israel/Palestine context. Sympathetic scholars can contribute by studying the mechanisms used to maintain Israeli oppression and identifying weak points where external pressure could induce change. However, it will remain for Palestinian activists themselves to build these evaluations into an overall strategy and supporting tactics, and to win mass support for this programme.

Finally, the South African analogy must be used appropriately. Its main force is moral, drawing an equivalence between the regimes to demand an equivalent international response. However, the alleged moral similarities of two targets tell us absolutely nothing about their relative vulnerability to BDS. Marked differences in social power relations, the degree and extent of opposition mobilisation, the mechanisms of rule, the political economy, and so on, mean that even identical sanctions produce very different outcomes in different times and places. Invoking South Africa may help to re-inspire the struggle for Palestinian freedom. However, as Marx warned, we must avoid ‘parodying the old’, or risk failing to confront present-day realities and priorities. The conditions that allowed South Africans to succeed do not exist in Israel/Palestine. They must be made anew.

* Research for this chapter was funded by an ESRC grant (RES-061-25-0500). I am grateful for research assistance from Sahar Rad, Zaw Nay Aung, Kyaw Thu Mya Han and Aula Hariri.

References

Abdalla, Jihan (2014) ‘A Palestinian Contradiction: Working in Israeli Settlements’, Al-Monitor, 18 February.

AFP (2013) ‘Israel Arms Sales In 2012 Rose By 20 Percent: Report’, 1 October.

Alexandrowicz, Ra’anan and Vilkomerson, Rebecca (2012) ‘An Effective Way of Supporting the Struggle’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 203-208.

ANC (1969) ‘Strategy and Tactics of the ANC’, Morogoro Conference, Tanzania, 25 April – 1 May; accessed at http://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/anc/1969/strategy-tactics.htm, 17 February 2014.

——— (1985) ‘The Nature of the South African Ruling Class’, Document of the National Preparatory Committee, ANC National Consultative Conference, Kabwe, Zambia, June; accessed at http://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/anc/1985/nature-ruling-class.htm, 17 February 2014.

Australians for Palestine (2010) BDS: Boycott, Disinvestment, Sanctions – A Global Campaign to End Israeli Apartheid, Melbourne: Australians for Palestine.

Awwad, Hind (2012) ‘Six Years of BDS: Success!’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 77-83.

Barghouthi, Mustafa (2012) ‘Freedom in Our Lifetime’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 3-11.

Barghouti, Omar (2011) Boycott, Disinvestment, Sanctions: The Global Struggle for Palestinian Rights, Chicago: Haymarket Books.

——— (2012) ‘The Cultural Boycott: Israel vs. South Africa’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 25-38.

——— (2013) ‘Palestine’s South Africa Moment has Finally Arrived’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 216-231.

Baroud, Ramzy (2013) ‘Palestine’s Global Battle that Must be Won’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 3-17.

Baum, Dalit and Amir, Merav (2012) ‘Economic Activism Against the Occupation: Working From Within’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 39-49.

Bethlehem, Ronald W. (1988) Economics in a Revolutionary Society: Sanctions and the Transformation of South Africa, Craighall: AD Donker.

Boesak, Allan (2011) Former patron, United Democratic Front, South Africa. Interviewed by telephone, 12 September.

Chamberlin, Paul T. (2012) The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Order, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, Robin (1986) Endgame in South Africa? The Changing Structures and Ideology of Apartheid, London: James Currey.

Crawford, Neta C. and Klotz, Audie (1999) ‘How Sanctions Work: A Framework for Analysis’, in Crawford, Neta C. & Klotz, Audie (eds.) How Sanctions Work: Lessons from South Africa, London: Macmillan, pp. 25-42.

Du Plessis, Barend (2011) Former South African Finance Minister, interviewed by telephone, 5 September.

Ella, Nadia (2012) ‘The Brain of the Monster’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 51-60.

Erakat, Noura (2012) ‘BDS in the USA, 2001-2010’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 85-97.

Erwin, Alec (2011) Former senior official, Congress of South African Trade Unions, interviewed in Cape Town, 12 September.

Falk, Richard (2013) ‘International Law, Apartheid and Israeli Responses to BDS’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 85-99.

Francke, Rend Rahim (1995) ‘The Iraqi Opposition and the Sanctions Debate’, Middle East Report 193: 14-17.

Free Burma Coalition (1997) The Free Burma Coalition Manual: How You Can Help Burma’s Struggle for Freedom, Madison: FBC.

Global Exchange (2003) Divesting from Israel: A Handbook, San Francisco: Global Exchange.

Gordon, Neve (2012) ‘Boycott Israel’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 189-191.

GPAAWC [Grassroots Palestinian Anti-Apartheid Wall Campaign] (2007) Towards a Global Movement: A Framework A For Today’s Anti-Apartheid Activism, June.

Hanlon, Joseph and Omond, Roger (1987) The Sanctions Handbook, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Hanna, Atallah (2013) ‘Towards a Just and Lasting Peace: Kairos Palestine and the Lead of the Palestinian Church’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 100-105.

Hever, Shir (2012) ‘BDS: Perspectives of an Israeli Economist’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 109-123.

——— (2013) ‘BDS: Perspectives of an Israeli Economist’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 109-123.

IRRC [Investor Responsibility Research Centre] (1990) The Impact of Sanctions on South Africa: Part II, Whites’ Political Attitudes, Washington, DC: IRRC.

Jones, Lee (2012) ‘How Do Economic Sanctions “Work”? Towards a Historical-Sociological Analysis’, paper presented at the International Studies Association/ British International Studies Association conference, Edinburgh, 20-22 June.

——— (2014) ‘How Do Economic Sanctions (Not) Work? Lessons from Myanmar’, paper presented at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, 29 January.

Khong, Yuen Foong (1992) Analogies at War: Korea, Munich, Dien Bien Phu, and the Vietnam Decisions of 1965, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lipton, Merle (1990) ‘The Challenge of Sanctions’, Discussion Paper no. 1, Centre for the Study of the South African Economy and International Finance, London School of Economics.

Lodge, Tom (1988) ‘State of Exile: The African National Congress of South Africa, 1976-86’, in Frankel, Philip, Pines, Noam & Swilling, Mark (eds.) State, Resistance and Change in South Africa, London: Croom Helm, pp. 229-258.

Maharaj, Mac (2011) ANC Senior Official, interviewed in Pretoria, 8 September.

Manzo, Kate and McGowan, Pat (1992) ‘Afrikaner Fears and the Politics of Despair: Understanding Change in South Africa’, International Studies Quarterly 36(1): 1-24.

Marx, Karl (1852) ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’, accessed at http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm, 15 June 2013.

Nabulsi, Karma (2010) ‘Lament for the Revolution’, London Review of Books 32(20): 34-35.

Pappe, Ilan (2013) ‘Colonialism, the Peace Process and the Academic Boycott’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 124-138.

Pedersen, Morten B. (2008) Promoting Human Rights in Burma: A Critique of Western Sanctions Policy, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Said, Edward W. (2002) The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After, 2nd ed., London: Granta.

Schlemmer, L. (1978) ‘External Pressures and Local Attitudes and Interests’, in Clifford-Vaughan, F. Mca. (ed.) International Pressures and Political Change in South Africa, Cape Town: Oxford University Press, pp. 75-85.

Sourani, Raji (2013) ‘Why Palestinians Called for BDS’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 61-71.

Starnberger Institute (1989) The Impact of Economic Sanctions Against South Africa, Harare: Nehanda.

Taraki, Lisa and LeVine, Mark (2012) ‘Why Boycott Israel?’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 165-174.

The Economist (2014) ‘A Campaign That is Gathering Weight’, 8 February.

Times of Israel (2014) ‘Most Israelis Support Peace Talks Freeze, Poll Shows’, 7 May.

US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation (2010) Divest Now! A Handbook for Student Divestment Campaigns; accessed at http://www.bdsmovement.net/2009/divest-now-handbook-5144, 10 June 2013.

van Wyck, Koos (1988) ‘State Elites and South Africa’s International Isolation: A Longitudinal Comparison of Perception’, Politikon 15(1): 63-89.

Warschawski, Michael (2012) ‘Yes to BDS! An Answer to Uri Avnery’, in Lim, Audrea (ed.) The Case for Sanctions Against Israel, London: Verso, pp. 193-197.

Ziadah, Rafeef (2013) ‘Worker-to-Worker Solidarity: BDS in the Trade Union Movement’, in Wiles, Rich (ed.) Generation Palestine: Voices from the Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions Movement, London: Pluto, pp. 179-192.