Analysis of the new direction of Hamas

A “NEW HAMAS” THROUGH ITS NEW DOCUMENTS

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol 35, no. 4 (Summer 2006

Khaled Hroub

Since Hamas won the Palestinian legislative elections in January 2006, its political positions as presented in the Western media hark back to its 1988 charter, with almost no reference to its considerable evolution under the impact of political developments. The present article analyzes (with long verbatim extracts) three recent key Hamas documents: its fall 2005 electoral platform, its draft program for a coalition government, and its cabinet platform as presented on 27 March 2006. Analysis of the documents reveals not only a strong programmatic and, indeed, state building emphasis, but also considerable nuance in its positions with regard to resistance and a two-state solution. The article pays particular attention to the sectarian content of the documents, finding a progressive de-emphasis on religion in the three.

Since its emergence in the late 1980s, perhaps the most important turning point in Hamas’s political life has been its unexpected victory in the January 2006 Palestinian Council (PC) elections in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Overnight, it was transformed from an opposition movement that had no part in the “national” governing structure to a party called upon to govern.

Inevitably, the realities and challenges brought about by this new circumstance could only accelerate a shift in the movement’s thinking and practice, a shift already signaled by its very decision to participate in the elections. From its establishment, Hamas had steadfastly refused to run in any national elections, either for PC or for the presidency of the Palestinian Authority (PA). As both these structures grew out of the Oslo accords, which Hamas opposed and considered illegitimate, it had never recognized the legitimacy of either. Thus, whereas the movement has long participated in municipal and other local elections, making its growing strength quantifiable, the question of whether to enter national electoral politics was a difficult decision, fraught with the contradictions that could be expected in a movement whose leadership is geographically divided between the “inside” and the “outside,” whose political and military wings have a degree of autonomy, and which adopts a democratic decision-making process with a diversity of views.

The focus of this paper, however, is not the movement’s history or internal dynamics, but rather the recent evolution of its intellectual and political lines as highlighted in three pivotal documents: the electoral platform drafted for its campaign in the fall of 2005; the draft National Unity Government Program, proposed to other Palestinian factions in March 2006 by a victorious Hamas as a basis for a coalition cabinet; and Hamas’s government platform after the collapse of coalition talks, as presented by Prime Minister–elect Ismail Haniyeh in his inaugural address to the PC on 27 March1. Despite the oft-repeated rhetoric of Hamas’s leaders that their movement will remain faithful to its known principles, the three documents reveal beyond question that the demands of the national arena have driven Hamas in dramatically new directions, confirming and going beyond profound changes that had been in the making for almost a decade. The movement’s widening perspective is clear even within the three documents: the electoral platform, drawn up at a time when there was little expectation of winning and still addressed primarily to supporters and sympathizers, is by far the most “sectarian” of the three documents, as will be seen. By contrast, Haniyeh’s speech outlining the government program presents a movement that clearly aspires to represent the entire Palestinian people.

Interestingly, these remarkable documents, so revealing of Hamas’s evolving thought and emphases, have received practically no coverage in the Western media or official circles. The first document has not been translated into English, as far as I know. The second has been partially translated in its main points, but not widely diffused. The third, though officially translated by Hamas itself, has to my knowledge been nowhere reproduced in its entirety or even in part. Instead, Hamas continues to be characterized with reference to its 1988 charter, drawn up less than a year after the movement was established in direct response to the outbreak of the first intifada and when its raison d’être was armed resistance to the occupation. Yet when the election and postelection documents are compared to the charter, it becomes clear that what is being promoted is a profoundly different organization.

THE ELECTORAL PLATFORM FOR “CHANGE AND REFORM”

Hamas chose to remain entirely on the sidelines of the November 2004 elections for president of the PA following the death of Yasir Arafat. Hamas believed that it would be illogical to present a candidate for the presidency of a body and indeed an entire system completely dominated by its traditional rival, Fatah. On the other hand, the movement’s remarkable successes in the municipal elections in recent years (winning about half the votes) encouraged it to participate in the first Palestinian legislative elections since 1996. The decision was announced publicly in March 2005. The very next day, according to one of Hamas’s leaders, the movement began to meticulously plan its campaign2.

In light of Hamas’s longstanding refusal to take part in national elections, it is not surprising that the Electoral Platform for Change and Reform begins with a political justification for its changed position. Thus, the first four paragraphs of the Electoral platform’s preamble (reproduced below in full) are entirely devoted to explaining why Hamas was running:

Compelled by our conviction that we are defending one of the greatest ports of Islam; and by our duty to reform the Palestinian reality and alleviate the suffering of our people, reinforcing their steadfastness and shielding them from corruption, as well as by our hope to strengthen national unity and Palestinian internal affairs, we have decided to take part in the Palestinian legislative elections of 2006.

The Change and Reform List believes that its participation in the legislative elections at this time and in the current situation confronting the Palestine cause falls within its comprehensive program for the liberation of Palestine, the return of the Palestinian people to their homeland, and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital. This participation [in the elections] will be a means of supporting the resistance and the intifada program, which the Palestinian people have approved as its strategic option to end the occupation.

Change and Reform will endeavour to build an advanced Palestinian civil society based on political pluralism and the rotation of power. The political system of this society and its reformist and political agenda will be oriented toward achieving Palestinian national rights. [In all this we] take into account the presence of the oppressive occupation and its ugly imprint on our land and people and its flagrant interventions in the details of the Palestinian life.

Presenting the platform of our list [to you] stems from our commitment to our steadfast masses who see in [our] course the effective alternative, and see in [our] movement the promising hope for a better future, God willing, and see in this list the sincere leadership for a better tomorrow. . . . [Quranic verse]

Though Oslo was not mentioned explicitly, it is clear that the preamble aims to distinguish between Hamas’s participation in the elections and its continuing rejection of the Oslo accords. Probably sensing that the explanation was not very persuasive—indeed, there is no doubt that whatever justifications were offered, both the PC and the elections were direct products of Oslo—Hamas returns to this point toward the end of the electoral platform, this time with explicit reference to the agreements.

The al-Aqsa intifada has created new realities on the ground. It has made the Oslo program a thing of the past. All parties, including the Zionist occupiers, now refer to the demise of Oslo. Our people today are more united, more aware, and stronger than before. Hamas is entering these elections after having succeeded, with God’s help, in affirming its line of resistance and in ingraining it deep in the hearts of our people.

Brothers and sisters: this is our program, which we put before you, sharing with you, hand in hand, our ambition. We do not claim to be able to work miracles, or to have a magic wand. But together we will keep trying to realize our national project with its great aims . . . one free and capable nation.

The fourteen-page Electoral Platform for Change and Reform constitutes without a doubt the broadest vision that Hamas has ever presented concerning all aspects of Palestinian life. Seventeen articles follow the preamble and a separate section entitled “Our Principles”: “internal politics,” “external relations,” “administrative reform and fighting corruption,” “legislative policy and reforming the judiciary,” “public freedoms and citizen rights,” “education policy,” “religious guidance and preaching,” “social policy,” “media and culture policies,” “women, children, and family issues,” “youth issues,” “housing policy,” “health and environment policy,” “agriculture policy,” “economic, financial, and fiscal policies,” “labor issues,” and “transport and border crossings.” These articles, each comprising a number of subpoints, form the body of the platform. Before addressing these, however, it is useful to reproduce the section “Our Principles” in full.

The Change and Reform List adopts a set of principles stemming from the Islamic tradition that we embrace. We see these principles as agreed upon not only by our Palestinian people, but also by our Arab and Islamic nation as a whole. These principles are:

1. True Islam with its civilized achievements and political, economic, social, and legal aspects is our frame of reference and our way of life.

2. Historic Palestine is part of the Arab and Islamic land and its ownership by the Palestinian people is a right that does not diminish over time. No military or legal measures will change that right.

3. The Palestinian people, wherever they reside, constitute a single and united people and form an integral part of the Arab and Muslim nation . . . [Quranic verse]. Our Palestinian people are still living a phase of national liberation, and thus they have the right to strive to recover their own rights and end the occupation using all means, including armed struggle. We have to make all our resources available to support our people and defeat the occupation and establish a Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital.

4. The right of return of all Palestinian refugees and displaced persons to their land and properties, and the right to self-determination and all other national rights, are inalienable and cannot be bargained away for any political concessions.

5. We uphold the indigenous and inalienable rights of our people to our land, Jerusalem, our holy places, our water resources, borders, and a fully sovereign independent Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital.

6. Reinforcing and protecting Palestinian national unity is one of the priorities of the Palestinian national action.

7. The issue of the prisoners is at the top of the Palestinian agenda.

Given Hamas’s traditional projection of itself as an uncompromising resistance movement, and the popularity it has derived from its resistance to the Israeli occupation, its choice of “change and reform” as the theme of its campaign and name of its electoral list may initially appear surprising; however, it rather cleverly draws attention to the failure and corruption associated with its rival Fatah. Perhaps even more surprising is the virtual absence of military resistance from the platform: there is simply no comparison between the weight and detail given to civilian aspects of governance promised by Hamas and the weight accorded to resistance. Indeed, the only places in the entire document that refer to resistance are the second paragraph of the preamble, point 3 of “Our Principles,” and the passage referring to the death of Oslo—all quoted above. Interestingly, in the single reference to “armed struggle” (in point 3 of “Our Principles”), the emphasis is on the right to end the occupation “using all means, including armed struggle.” The other two references are not only very general, but are actually, as noted above, used to justify Hamas’s participation in the elections: in the preamble, running in the elections is cast as a way of supporting the resistance, and the passage at the end of the document implies that it was Hamas’s success in affirming its “line of resistance” that made its participation in the elections possible.

While the preamble and “principles” form the essential background to Hamas’s program, the overriding thrust of the document is the domestic scene, with particular emphasis on governance and reform. Under the heading “internal politics,” Hamas outlines its “civic” outlook and the prerequisites for national unity based on consensus and pluralism:

The organizing system of the Palestinian political action should be based on political freedoms, pluralism, the freedom to form parties, to hold elections, and on the peaceful rotation of power. These are the guarantees for the implementation of reforms and for fighting corruption and building a developed Palestinian civil society. . . . [Hamas will] adopt dialogue and reason to resolve internal disputes, and will forbid infighting or the use or threat of force in internal affairs. [Hamas will] emphasize respect for public liberties including the freedom of speech, the press, assembly, movement, and work. [Hamas] forbids arbitrary arrest based on political opinion. It will maintain the institutions of civil society and activate its role in monitoring and accountability. [Hamas] will guarantee the rights of minorities and respect them in all aspects on the basis of full citizenship. . . . [P]ublic money belongs to all Palestinians and should be used for comprehensive Palestinian development in ways that fulfill social justice and fairness in geographical distribution without misuse, squandering, usurpation, corruption, and defalcation.

The emphasis on reform permeates the entire document; indeed, it could be said that the document was designed to carry out exactly the kinds of reform that had been demanded by Western governments and financial institutions. On “administrative reform and fighting corruption,” Hamas promises to

fight corruption in all its forms because it is one of the main causes contributing to weakening our internal front and shaking the foundation of national unity. [Hamas] will investigate all issues pertaining to financial and administrative corruption and subject to judicial punishment all people found guilty of corruption. [We] will stress transparency and accountability in dealing with public funds . . . [and] modernize laws and regulations in order to increase the efficiency of the executive system . . . and embrace decentralization and delegation of power and participation in decision making. [Hamas] will revise the policy of public employment in ways that will guarantee equal opportunities on the basis of qualification.

With regard to “legislative policy and reforming the judiciary,” the electoral platform pledges to

stress the separation between the three powers, the legislative, executive and judicial; activate the role of the Constitutional Court; re-form the Judicial Supreme Council and choose its members by elections and on the basis of qualifications rather than partisan, personal, and social considerations . . . ; enact the necessary laws that guarantee the neutrality of general prosecutor . . . [and] laws that will stop any transgression by the executive power on the constitution.

On “public freedoms and citizen rights,” the aim is to

achieve equality before the law among citizens in rights and duties; bring security to all citizens and protect their properties and assure their safety against arbitrary arrest, torture, or revenge; stress the culture of dialogue . . . ; support the press and media institutions and maintain the right of journalists to access and to publish information; maintain freedom and independence of professional syndicates and preserve the rights of their membership.

Above and beyond broad issues of governance, the electoral document ventures into programming. Despite its efficient operation of a vast network of social service organizations, Hamas (as well as other Islamist movements) are typically accused of giving priority to rhetoric and mobilization over pragmatic programming, and it is clear that this accusation was in the mind of those who drafted Hamas’s electoral platform. Moreover, while Hamas has always dealt with education and various other social service areas, its entrance into “national politics” and public resources entailed addressing “new” areas such as youth, housing, and the environment. With regard to youth, the platform promises to “establish more youth institutions, to support sports clubs and stop external intervention in their affairs; to support talented youth in all fields and to create job opportunities for young people, especially university graduates; to support athletic teams in all sports and to build new facilities so that the teams can participate in tournaments at local, Arab, Islamic, and international levels.”

With regard to housing, Hamas promises “to allocate public land to build housing projects and villages for people with low income, especially those whose houses have been demolished by Israel . . . ; to take the problem of housing off the shoulders of the poor and tackle the problems of densely-populated areas in the West Bank and Gaza Strip; focus on the construction sector by eliciting easy repayment and financing in order to activate this sector rapidly . . . which will bring back skilled Palestinian manpower that used to work in the Israeli construction market.”

As for the environment, the platform calls for “maintain[ing] a clean environment through developing a culture focused on a dirt-free public sphere, planting trees along roads, and building parks and encouraging private and public green areas; protect[ing] the environment and stop[ping] the deterioration of Palestinian environment in coordination with international agencies . . . ; keep[ing] Gaza’s beaches clean and beautiful and receptive to tourism.”

Since one of the main objections to Hamas has been its perceived determination to Islamize society, it is worth examining with some care the religious content of its electoral platform. In fact, the religious references are relatively few: when combined they amount to about a page and a half out of the document’s fourteen pages, including the five Quranic verses. Leaving aside the verses (quoting from the Quran being a common practice in political speeches and documents throughout the Islamic world, including by secular figures and bodies), the most overtly religious references appear in the preamble (first line) and “Our Principles” (the first three points), both quoted above, and in the final appeal at the very end of the document. This last is without doubt the most blatant, and makes abundantly clear that while Hamas was striving to expand its base, it was still thinking primarily in terms of its traditional constituency. The appeal reads as follows:

When you cast your ballot, remember your responsibility before God. You bear responsibility for choosing your representative to the legislative council. When this representative decides on issues pertaining to religion, the homeland, and the future, he represents you, so make the right choice that will please God and His Messenger (peace be upon him), who said: “The best whom you should employ is the strong and the honest.” Yes, make the right choice, that you may please God and your people, God willing. Islam is the solution, and it is our path for change and reform.

Six other articles have at least one reference to Islam. Except for the “Religious Guidance and Preaching” section, the Islamic references are overshadowed by clauses that would be standard in any secular document. Nonetheless, it was these articles of the Electoral Platform that stirred controversy among secular Palestinians, perhaps because they dealt with practical matters rather than general principles. The Islamizing content of the six articles is summarized below.

• Education: the first of the article’s seventeen points, which sets the general framework for education, reads: “[we call] for the implementation of the foundations that underpin the philosophy of education in Palestine. The first of these is that Islam is a comprehensive system that embraces the good of the individual and maintains his rights in parallel with the rights of society.” There is no further mention of Islam in the education article, which deals with such items as developing and improving syllabi, expanding elementary schooling, emphasizing social sciences, and encouraging private sector investment in higher education.

• Social policies: two of the article’s sixteen points, dealing with resisting corruption and fighting drugs and alcohol, refer to Islamic values as a source of strength and wholesomeness that help preserve “social norms.” The rest of the article tackles a wide array of issues such as creating social support networks, expanding social services to reach everybody, subsidizing the associations focused on women’s and child welfare, fighting poverty, and establishing workable pension systems.

• Religious guidance and preaching: All five points of this section—dealing with the qualifications and status of imams, security interference in the religious sector, the maintenance of mosques, pilgrimage issues, and so on—refer to Islam.

• Legislative policy and reforming the judiciary: the first of the thirteen points stipulates that “Islamic shari`a law should be the principal source of legislation in Palestine.” Islam is not mentioned in any of the other points, which are almost entirely focused on establishing a sound and efficient legal system based on the separation of powers. Particular attention is given to the need to activate the “constitutional court” and to choose the members of the Supreme Council of the Judiciary by election, not appointment.

• Women, children, and family issues: One of eight points carries the advice: “fortify woman by Islamic education, make her aware of her religious rights and confirm her independence which is based on purity, modesty, and commitment.” The other points relate to areas such as the introduction of new laws and regulations to protect women’s and children’s rights, encouraging and facilitating work for women, and supporting mothers through special social support and health care programs.

• Media and culture policies: None of the eight points of this article—which deal with such matters as freedom of expression, the role of media in supporting the steadfastness of the Palestinians, and improving professionalism—mention Islam directly. Secularists, however, see an Islamic subtext in the injunction to “fortify citizens, especially the youth, against corruption, Westernization, and intellectual penetration.”

The remaining eleven articles of the electoral platform—on “internal politics,” “external relations,” “administrative reform and fighting corruption,” “public freedoms and citizen rights,” “youth issues,” “housing policy,” “health and environment policy,” “agriculture policy,” “economic, financial, and fiscal policies,” “labor issues,” and “transport and crossings”—make no mention of religion whatsoever. The absence of any Islamic reference in two of these articles may seem surprising: “Internal politics,” where one might expect some allusion to Islamizing programs or policies; and “economic and fiscal policies,” where the programs of many Islamist movements call for moving toward an “Islamic economy” or criticize “un-Islamic” banking practices (such as interest on loans).

Though the language of the electoral platform overall is secular and bureaucratic, the religious references that it does contain fuelled suspicions (arising from Hamas’s origins and history) that the movement was quietly working toward its true agenda, the Islamization of society. For its part, Hamas justifies its Islamic language and positions on the grounds that they reflect the true nature and aspirations of society. In fact, the boundary here is blurred: while many people vote for Hamas at least partly because of its Islamic aspects, others prefer to ignore them and support Hamas for other reasons.

THE PROPOSED NATIONAL UNITY GOVERNMENT PROGRAM

Hamas went all out during the campaign for the 25 January PC elections, expecting to win a significant bloc of seats but not a majority. Surprised and even ambivalent about its victory, it was eager for a power sharing arrangement within the framework of a coalition government. There is no doubt that the desire for a coalition was at least partially motivated by a sense of ill-preparedness to move abruptly from total nonrepresentation in government to assuming full power. But there is also no doubt that Hamas had long emphasized national unity and had long signaled its readiness to join PA structures and the PLO, albeit on its own terms. Thus, a national unity government was not only very much in line with Hamas’s thinking, but was also seen as the best possible way forward. The second document under discussion, the draft National Unity Government Program, represents Hamas’s attempt to persuade it rivals, primarily Fatah, to join.

Immediately after its defeat in the elections, Fatah leaders stated that they would not join a Hamas-led government; one frequently expressed comment was that Hamas should be made to “dirty itself” in power politics, thus depriving it of the “oppositional purity” it had long enjoyed while outside the system. On the other hand, other factions, particularly the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), did express interest in being part of a national unity government. In early March, Hamas presented its draft program and extensive consultations were held with the various groups. Prime Minister Haniyeh’s remarks concerning the consultations in his 27 March speech to the PC presenting the government program (see below) are worth quoting:

[W]e wanted to face the challenges lying ahead unified and in a coalition government. We devoted every effort and energy to form a national coalition government. During the last few weeks, a lot of effort was spent to achieve this noble goal. We worked sincerely, seriously, and strenuously in our marathon dialogues with brothers in the other parliamentary blocs and factions to find a common ground that guarantees participation of all in this government and, in particular, brothers in [the] Fatah movement. We also extended consultation and dialogue to include non-represented factions who chose not to participate in the PC elections, namely our brothers in [the] Islamic Jihad movement. In our negotiations with them, we suggested a number of drafts and introduced numerous modifications on the political program for a national coalition. . . . Unfortunately, our brothers in the parliamentary blocs preferred not to participate in this government.

Whatever the results of the “marathon dialogues,” Hamas’s proposed national unity government platform was rejected by the factions. Ostensibly, there were two main reasons: Hamas’s failure to acknowledge the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and its refusal to subscribe to the UN resolutions on Palestine and Israeli-PLO agreements. In fact, however, the negotiations were doomed from the start. The deep mistrust between Hamas and other factions that built up over the years was too great to be overcome in so short a time period. As mentioned above, Fatah never had any real intention of joining a coalition, preferring to “wait it out” in the hopes that Hamas’s days in power would be numbered. As for the PFLP and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), as well as some independents, in addition to the role undoubtedly played by Hamas’s refusal to acknowledge the PLO, there is some evidence of internal and (at least indirect) external pressures not to join. Contributing to the reluctance of certain independent PC members was the possible consequence of participation on their future exclusion by influential internal or external players. Nonetheless, despite the collapse of the coalition talks, the document is important for the insight it provides into Hamas’s thinking and its desire to work with its rivals to reach common grounds. Significantly, following the failure of the coalition talks, Hamas’s final government program did not backtrack on any of the articles sketched in the National Unity platform.

The document comprises a preamble and thirty-nine articles. The preamble states the aims of the national unity program, including in particular “preserving non-negotiable national imperatives . . . protecting the rights and interests of the Palestinian people, . . . realizing their national rights to end the occupation and preserve the [refugees’] right of return and resistance, . . . and build[ing] an independent, completely sovereign Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital.”

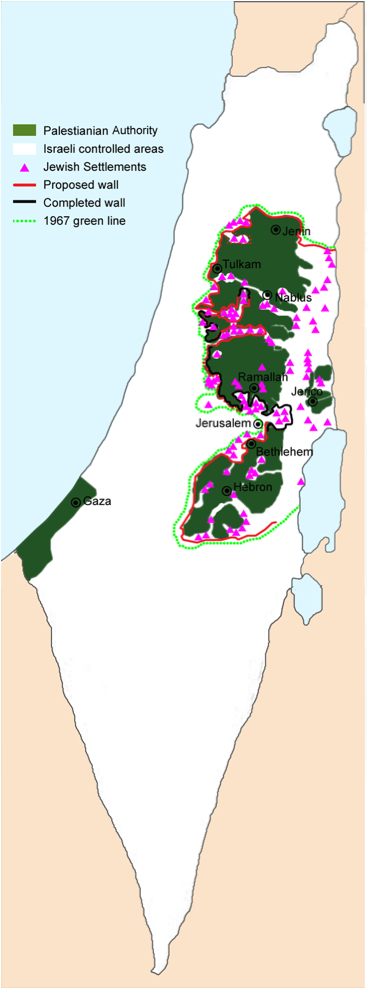

The first few articles lay out top priority issues and principles shared by all Palestinian factions: ending the occupation and dismantling the settlements, working toward building the Palestinian state, and rejecting partial solutions (article 1); upholding the refugees’ right of return to their homes (article 2); liberating prisoners, combating Israeli measures such as assassinations, incursions, the Judaization of Jerusalem, the annexation of the Jordan Valley, the separation wall, and so on (article 3); and resistance, “in all its forms,” as a national right (article 4).

As already indicated, one of the major problems confronting Hamas following its victory was external pressure to recognize international conventions and agreements on Palestine. A number of articles reflect Hamas’s attempt to grapple with these issues. Article 5 calls for “Cooperating with the international community for the purpose of ending the occupation and settlements and achieving a complete withdrawal from the lands occupied [by Israel] in 1967, including Jerusalem, so that the region enjoys calm and stability during this phase.” Two articles attempt to provide assurances that the Hamas-led government will function within the international conventions and agreements on Palestine: Article 9 confirms that “The government will deal with the signed agreements [between the PLO/PA and Israel] with high responsibility and in accordance with preserving the ultimate interests of our people and maintaining its rights without compromising its immutable prerogatives,” while article 10 states that “The government will deal with the international resolutions [on the Palestine issue] with national responsibility and in accordance with protecting the immutable rights of our people.”

Clearly, articles 9 and 10 did not go far enough to satisfy either the international community or Fatah. They did, however, represent a major shift on Hamas’s part, showing an obvious attempt to maintain a delicate balance between appeasing international observers and Hamas’s own constituency. Thus, the program contains vestiges of the traditional policy of “stages” whereby a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip is seen as the first phase to liberate the entire land of Palestine. Delivering such a message to Hamas supporters is the objective of the phrase in article 5 “during this phase.” At the same time, taken as a whole, the thrust of these articles—and the entire document—hovers around the concept of the two-state solution without a hint of the “liberation of the entire land of Palestine” or “the destruction of Israel” found in the charter. Except for article 2 upholding the refugees’ right of return, all references in the document are to territories occupied in 1967 (the West Bank, Jordan Valley, “Apartheid wall,” and so on); article 4 regarding resistance proclaims it as a “legitimate right to end the occupation” (emphasis added). The specific mention in article 5 of “complete withdrawal from the lands occupied in 1967” (emphasis added) clearly implies a two-state solution, while the reference in article 10 to international resolutions and in article 3 to the need to “activate the resolution of the International Court of Justice [against the wall]” both show at least implicit recognition of the legitimacy of international law and mechanisms.

A major sticking point between Hamas and the factions, as noted above, was that the document stopped short of recognizing the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinians. The issue of Hamas joining the PLO had been under serious discussion in the intermittent Palestinian “national unity” dialogue since January 2005; what prevented the move was Hamas’s insistence that its representation on the PLO’s National Council should be proportional to its popular strength as measured in opinion polls, and, since the PC elections, that it should it should have something between 40 and 50 percent of the seats. As the concept of proportional representation was denied, Hamas’s position has been that the PLO cannot be called the “sole legitimate representative” if a group representing nearly half of the population is excluded from it. In light of this impasse, article 8 merely states that “The government reiterates what has been agreed upon in the Cairo dialogue of March 2005 between the Palestinian factions on the subject of the PLO, and emphasizes the need to speed up the measures required to that end.” The March 2005 understandings called on the PLO to undertake urgent and comprehensive reforms, including admitting Hamas and Islamic Jihad, after which Hamas would recognize the PLO as the sole legitimate representative.

As was the case with the electoral platform, “reform” constitutes a major theme in the proposed national unity document. Article 6 promises to “Undertake comprehensive in-house reform; fight corruption; tackle unemployment; build a society and institutions on democratic foundations that guarantee justice, equal participation, and political pluralism; stress the rule of law with complete separation between powers where the independence of the judiciary should be guaranteed and human rights and basic liberties protected.” Article 23 calls for “Developing administrative and financial reforms, strengthening the role of oversight and accountability, establishing a diwan al-mazalem (court of complaints and injustices), activating the laws against illegal profiteering, corruption, and the squandering of public funds”; article 7 emphasizes rebuilding institutions on democratic, professional, and nationalist foundations rather than on the basis of “unilateralism” (a code word for one-man or one-party rule) and factional affiliation. Other articles call for “the independence of national Palestinian decision-making” (article 11), the peaceful rotation of power (article 15), reinforcing the rule of law (article 18), and judiciary reform, including raising its performance standards and supporting the implementation of its decisions (article 20).

On civil society and public freedoms, the government promises to bolster civil society and develop its institutions (article 22); safeguard private and public liberties, asserting free expression and the formation of parties, and outlawing political arrests (article 21); “reinforce the role and independence of media institutions, and protect the rights and freedom of the press and journalists, and facilitate their work” (article 38); activate and support the role of professional and general associations and unions (article 39); guarantee the safety of the citizen and homeland, individual and public property (article 29); and enhance the principle of equal opportunities and outlaw employment dismissals on political or partisan ground (article 23).

On social matters, the document pledges that the government will safeguard the rights of the poor and the weak and maintain the rights of people with special needs, including by supporting the institutions that provide them with assistance (article 26); improve the living conditions of the population, encourage social solidarity, and expand safety nets in social, health, and educational matters, and develop all types of services for the citizens (article 27); safeguard the rights of women, children, youth, and families, and asserting their role in building the homeland (article 29); strengthen the role of youth and increase their participation in building the nation, and support youth institutions and develop their performance (article 30); prepare a comprehensive national plan to tackle problems of poverty, unemployment, labor, and education (article 31); enhance the performance of the institutions that provide welfare for the families of martyrs, the wounded, and prisoners (article 24); and encourage the housing sector to alleviate the housing problem for young and poor married couples (article 32).

With regard to development and the economy, the platform calls for the preparation of a comprehensive national development plan, with special attention to human development (article 28); the building of economic institutions designed to promote investment, raise growth rates, prevent monopolies and exploitation, protect workers, encourage manufacturing and exports, promote international trade (especially with the Arab world), and pass legislation appropriate for these ends (article 36); and the development of agriculture, livestock and fisheries, and food exports and the food industry in general (article 35).

The national unity platform contains almost no religious references, and those that do exist seem primarily linked to support for the national cause. Thus, article 12 calls for “asserting our Arab and Islamic dimension and activating the support of our Arab and Islamic nations for our people and its just cause in all aspects.” Support for the cause becomes explicit in article 13, which calls for “establishing good, positive, cordial and balanced relationships based on mutual respect with Arab, Islamic, and other states, and with international institutions.” Article 37 does not directly mention Islam, but its call for “strengthening the role of cultural institutions, with attention to [both] the Palestinian and Arab heritage, and to fortify citizens against [foreign] intellectual penetration”—reproduced from the electoral platform—was interpreted by some as an implicit call for an Islamic agenda. Still, the road traveled with regard to religious content since the electoral platform drafted several months earlier is striking.

THE CABINET PLATFORM

The most important of the three documents discussed is the cabinet platform delivered by Prime Minister–elect Ismail Haniyeh on 27 March 2006 in a speech before the newly elected parliament. What makes the platform especially interesting is that it represents Hamas alone, having been drafted after the collapse of the national unity negotiations when there was no longer any need to make concessions to the factions. Yet, far from any retrenchment onto more traditional positions, if anything the document represents advances on certain points.

Though its primary purpose was to present the government program, “hoping that it will receive your confidence so that we may begin its implementation,” at the same time Hamas was clearly, in carefully crafted language, seeking to address diverse audiences and to convey various messages, not always easy to reconcile. It sought to reassure the wider Palestinian public that their interests were the supreme preoccupation of the government and to convey to Fatah and the other electoral losers its desire to work together. It sought to signal to Israel its nonbelligerency and expectation of smooth interaction in “necessary contacts in all mundane affairs,” even while emphasizing Palestinian suffering from Israeli policies and the Palestinians’ legitimate right to resist the occupation. It sought to overcome or temper the alarm in the West caused by its victory, emphasizing its commitment to responsible governance and to agendas long promoted by the international community. It sought to portray itself to the neighboring skeptical Arab regimes, which feared the ramifications of a Hamas victory on their domestic affairs, as a responsible, trustworthy, and moderate government. At the same time, it had to live up to its promises and the expectations of its own constituency, and to reassure other Islamist movements and exponents of political Islam in the Middle East and beyond that the Hamas in power would be the same as the Hamas they had always known.

From the beginning of Haniyeh’s speech, the tone was moderate and conciliatory toward the other Palestinian factions. Continuity with gradual change, rather than a break with the past, was signaled even in the early reference to the birth of the “tenth” Palestinian Council under conditions of “continuing occupation and aggression”; indeed, it would appear that one of the aims of the frequent references to the occupier’s measures was to reinforces the idea both of continuity and that all Palestinians were facing the same situation, with the obvious consequence that “We have no choice but to work together to protect this blessed homeland.” Contributing to the sense of continuity and conciliation was Haniyeh’s warm praise of PA President Mahmud Abbas at the very beginning of his speech. Abbas, an architect of the Oslo accords, had previously been the target of strong Hamas attacks. Here, however, Haniyeh pays tribute to him “for his outstanding role in holding the legislative elections and in reinforcing Palestinian democratic foundations” and for his determination “to harness, nurture, and protect political pluralism.” Haniyeh goes on to emphasize

not only our respect for the constitutional relationship with the president, but also our interest in strengthening this relationship for the sake of serving the interests of our people, and safeguarding [our] legitimate principles. We are committed to settling our differences in political positions and policies through dialogue, cooperation, and continuous coordination between the presidency and the other national institutions, first and foremost the PLO, on the basis of mutual respect and the protection of constitutional and functional powers at each level.

Haniyeh also thanks “Brother Ahmed Qurai` and his government” for their “cooperation and care to make a smooth transition of power” and all the former ministers and PC members, especially “Brother Rawhi Fatouh, former speaker of our PC.”

The theme of “dialogue, cooperation, and consultation” and the government’s intention to “cooperate responsibly with all factions of our people” is sounded frequently throughout the address. After describing the negotiations with the factions for a national unity government, Haniyeh explains that Hamas had worked hard to form such a government

because we believed and still believe that our success hinges upon our coalition, and that in our unity lies development and reform for a better future. . . . We respect their decision [not to join]. However, we say the following: Despite our failure to form a national coalition government, we must succeed in preserving our national unity. We will not lose hope and we will continue to work to reinforce our national unity [and] put the Palestinian house in order to strengthen our home front. Our hands will remain extended to all. Consultation and dialogue on all issues of common concern will always remain our policy to achieve the supreme national interests of our people and nation. The door for participation in the government will remain open. This homeland is for all, it is the destiny and future of all. (Emphasis added)

Nonetheless, Hamas did not substantially alter its position on the points of discord. Though Haniyeh alludes several times in the course of his speech to the PLO’s primacy among national institutions (“the need to enhance and empower the national institutions, at the top of which is the PLO”), his direct remarks concerning the organization essentially reiterate, with some elaboration, article 8 of the national unity platform:

Pertaining to the PLO, the government appeals to all factions, powers, and functionaries to work together to implement the Cairo understandings. We will work together to preserve the PLO because it is the framework that embodies our people’s hopes and ongoing sacrifices to restore their rights. The PLO is the institution that built up the struggle that we are proud of, and we wish to develop and reform it through consultation and dialogue. In this regard, we stress the need to speed up the implementation of the necessary measures to complete [the restructuring] of the PLO, thus allowing other Palestinian factions to join it on sound democratic foundations that permit political partnership, the PLO being the umbrella for all Palestinians at home and in the diaspora, and which represents and nurtures their interests, shoulders their concerns, solves their problems, and protects their national rights.

Similarly, Haniyeh’s language concerning his government’s approach to the agreements with Israel and the “international resolutions pertinent to the Palestinian cause” is virtually identical to that of articles 9 and 10 of the National Unity Government Program: the government will deal with both “with high national responsibility” while protecting the rights and interests of the people and national principles. There was, however, one significant advance in the diplomatic realm. Whereas Hamas had long been dealing unofficially with Israel within the framework of the municipalities under its control, this had never been openly acknowledged before the government platform presented by Haniyeh: “The government and relevant ministries will take into consideration the interests and needs of our people and the mechanisms of daily life, thus dictating necessary contacts with the occupation in all mundane affairs: business, trade, health, and labor.”

Despite the refusal to formally recognize the PLO-Israel agreements or international resolutions on Palestine, the concept of the two-state solution is everywhere between the lines in Haniyeh’s speech, including in his insistence “on the Palestinian geographical unity and the need to link the two halves (West Bank and Gaza) of the homeland politically, economically, socially, and culturally. Parallel to this, we also emphasize the importance of linking the Palestinian people at home and in the diaspora.” The reference to the West Bank and Gaza as the “two halves,” with no reference to the “rest of the homeland” in between (i.e., Israel proper) is highly significant. Haniyeh’s statement toward the end of the speech that his government will operate “in accordance with the articles of the modified Basic Law of 2003” is similarly significant, since the Basic Law is rooted in and emerged from the Oslo accords. The references throughout the speech to “constitutional rights” and to Hamas’s respect for the “constitutional relationship” with President Abbas should be seen in the same light. As in the case of the electoral platform and the national unity program already discussed, there is not the slightest hint of an intention to destroy Israel. Indeed, the speech could be said to represent an advance over the other two in this regard in that there is no reference to either “armed struggle” (as in the preamble of the electoral platform) or “the current phase” (as in article 5 of the national unity platform).

With regard to peace initiatives and agreements, mention might be made of the document’s reference to Arab efforts, and in particular to the Saudi-led initiative endorsed by the 2002 Arab League summit in Beirut (immediately dismissed by Israel and the U.S.), which called for full Arab normalization with Israel in exchange for full Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 borders. In his address, Haniyeh, stated that his government would “encourage any Arab and Islamic political move to restore national rights of the Palestinian people, including the right to establish an independent fully sovereign Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital,” and then went on to “remind the world that the occupation authorities have always ignored the Arab peace initiatives, including the 2002 Arab summit initiative in Beirut. The problem has never been from the Palestinian or the Arab side. Rather, the problem is with the Israeli occupation.” Here, as on the other peace plans, the Hamas line has been that Hamas should not be forced to sign onto agreements or initiatives that Israel either rejects outright or sidesteps.

Obviously, the core of Haniyeh’s speech was his government’s program. In introducing it, he listed seven major challenges that would constitute the agenda: (1) resisting the occupation and its ugly practices on the ground against the Palestinian people, land, holy places, and resources; (2) providing security and ending the lawlessness and anarchy in the Palestinian areas; (3) relieving the economic hardships facing the Palestinian people; (4) undertaking reform and fighting financial and administrative corruption; (5) putting the Palestinian house in order by reorganizing Palestinian institutions on a democratic basis that would guarantee political participation for all; (6) raising the status of the Palestinian question at the Arab and Islamic levels; and (7) developing relations at the regional and international levels to serve the supreme interests of our people.

Much of the almost 6,000-word speech spells out programs aimed at meeting these challenges or elaborates on underlying premises. Basically, these sections are an expansion of the articles of the draft national unity government platform, emphasizing good governance, matters of social justice, various aspects of economic and administrative reform, the rule of law, and the judiciary. Having already sketched out these basic issues in the preceding section, there is no need to revisit them. However, several points mentioned in the national unity document were elaborated in the cabinet program presented by Haniyeh and deserve mention.

First, the notion of citizenship was developed. Interestingly, the emphasis in this document, issued by an Islamist movement seen as playing on primordial identities to win support, appears to be on a citizenship that transcends narrower allegiances. Thus,

We [fully] realize that reinforcing shura (consultancy) and democracy requires hard work to impose the rule of law, renounce factional, tribal and clan chauvinisms, and lay the foundation for the principle of equality among people in terms of duties and rights. The government will work to protect the constitutional rights of all citizens so as to protect the Palestinian people’s rights and freedom. . . . The government also undertakes to protect the rights of every citizen and to firmly establish the principle of citizenship without any discrimination on the basis of creed, belief or religion, or political affiliation.

This idea is repeated near the end of the document: “We stress the need to reinforce the spirit of tolerance, cooperation, coexistence among the Muslims, the Christians, and the Samaritans in the framework of citizenship that does not discriminate against any on the basis of religion or creed.”

An issue given passing mention in the national unity document but given considerable attention here is the role of investment in building the economy. Even while continuing to emphasize social justice, social welfare allocations, care for the poor, and programs to reduce unemployment, an underlying free-market thinking is striking. “Investment,” Haniyeh declares, “is a basic pillar in sustainable development. Donations and aid, despite their importance and necessity at this stage, cannot be counted on. Therefore, one of the top priorities of our economic program is promotion of investment in Palestine. Our government will be highly prepared to discuss all details pertinent to providing necessary incentives and guarantees for foreign investment. . . . [To this end, we will provide] conducive investment conditions to realize good financial returns.” In particular, he appealed to “Palestinian Arab and Muslim entrepreneurs to come to Palestine and discover investment opportunities in various sector of the economy. We promise to provide them with every possible help and create an investment climate, security, and economic protection through enactment of necessary laws and legislations.”

The effort to reassure donors is similarly evident, though the bid for aid is prefaced by reference to the circumstances that make it necessary. Thus, while the aim of the economic program is to achieve “sustainable development, by optimum utilization and tapping of our own human and natural resources,” the government recognizes that “the surrounding political conditions created by the [Israeli] occupation, prolonged closure and siege of cities have severely destroyed much of our infrastructure,” thus “forcing us” to seek “badly needed aid and support from the international community, our brethren and friends in the world.” In an implicit but clear reference to donor concerns about PA corruption, Haniyeh stressed that the government would “provide all necessary guarantees and mechanisms to monitor the spending process of the financial aid to make sure that the money is managed properly and in accordance with approved plans, projects, and programs.”

By the time Haniyeh presented his government in late March, the U.S.-led boycott against the PA was in full force. Earlier in his speech he had alluded in passing to the exemplary conduct of the elections and warned against punishing the Palestinian people for exercising their right to democratically choose their leaders. In addressing the aid issue, he returned to this subject, deploring the “hasty decisions taken in the wake of the PC elections, and particularly by the U.S. administration” to stop aid, and appealing to “the international community to reconsider its position . . . and to respect the democratic choice of the Palestinian people.”

The statement pledged to work to establish solid relations with all countries “and all international bodies including the UN and the Security Council.” It commended the European Union (EU) for its generous support of the Palestinian people and its “serious positions” and criticisms of occupation policies, adding, however, that “we expect it to play a bigger role in exercising pressure on the occupation forces to withdraw from the occupied Palestinian territories.” Haniyeh ends his appeal to the international community as follows:

Our government expects the international community and particularly the Quartet to side with the values of justice and fairness for the sake of a just and comprehensive peace in the region and not to side with one party at the expense of the other. We expect the international community to end its threats to impose sanctions against the Palestinian people because of their democratic choice. In this respect, the government [highly] appreciates the position of Russia, a Quartet member, which has chosen dialogue instead of threats and warnings. Our government is and [will be] ready for dialogue with the Quartet to explore all avenues to put an end to the state of conflict in the region and bring peace to the region.

In contrast to the relatively friendly tone used in references and appeals to the EU, the United Nations, and Russia, the statement concerning the United States is at best terse:

The American administration, which has been preaching democracy and the respect of people’s choices, is called before all others to support the will and choice of the Palestinian people. Instead of threatening them with boycotts and cutting aid, it should fulfill its promises to help in the establishment of an independent Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital.

CONCLUSION

These three documents represent in themselves an evolution in Hamas’s political thinking toward pragmatism and the Palestinian “mainstream,” with the cabinet platform presented by Haniyeh reflecting very little inclination to radical positions. It is highly significant that the major reference to resistance in Haniyeh’s speech highlights its importance in the past. Instead, the emphasis in the new phase is on state building.

Our people have shown all creativity in their resistance to the occupation and set an example of patience, sacrifice, and steadfastness. Their creativity will also, God willing, be displayed in building and construction and in reinforcing the democratic choice, something that, if it succeeds, will be a model to be followed by freedom fighters and noble people in the world.

Religious overtones are similarly downplayed, and it is interesting to look for indications of a Hamas authorship while reading Haniyeh’s text. Certainly, there are five short Quranic verses as well as one of the Prophet’s teachings (hadith), which is not unusual in such speeches delivered by Arab and Muslim officials on such occasions. When saluting Palestine’s “revered martyrs,” Hamas’s Shaykh Ahmad Yasin and `Abd al-`Aziz Rantisi and Islamic Jihad’s Fathi Shiqaqi are listed immediately after Yasir Arafat. When describing the consultations for a unity government, Haniyeh makes an overture to Islamic Jihad, something the secular factions might have thought twice about.

For the most part, however, the references to Islam are general, having to do either with the nature of Palestinian society (e.g., “The Palestinian people are an integral part of our Arab and Muslim nation”; the government’s strategy of reform will “benefit from the experiences of others in the areas of institutionalization of society, democratic issues, human rights and public freedoms while taking into consideration our unique Palestinian, Arab, and Islamic particularisms in keeping with our people’s political, social, and historical realities” [emphasis added]), or in relation to the Palestinian cause. Examples of the latter include references to the need to strengthen “ties with the Arab and Islamic countries’ rulers, people, scholars, Islamic and national movements, [and] political and ideological elites . . . [to] create a climate for an Arab and Islamic effort to secure our people’s rights” and statements such as “Our government will strive for the deepening of relations and consultation with the Arab and Islamic surrounding, for it is our strategic depth. . . . Our cause is both an Arab and Muslim responsibility, and therefore it touches not only the life and future of the Palestinian people but also the life and future of all Arabs and Muslims.” There are no longer any Islamic references in the programmatic sections. The closest one comes to an overt Islamic appeal is the vow to remain faithful to “Islamic tolerant values”; this appears toward the end of the document in a passage quoted in its entirety below:

May God help us in shouldering the trust given to us by our people. We promise our people, martyrs, prisoners, the wounded, and freedom fighters, at home and in the diaspora, that we will remain faithful to our principles, the values we have committed ourselves to. We will remain faithful to Palestine and its glorious history. We will also be faithful to Islamic tolerant values. We stress the need to reinforce the spirit of tolerance, cooperation, coexistence among the Muslims, the Christians, and the Samaritans in the framework of citizenship that does not discriminate against any on the basis of religion or creed. At the same time, we emphasize the necessity to work seriously, at the local, Arab, and international levels, and by all means possible, to protect our Islamic and Christian holy places, particularly in Jerusalem, from Judaization.

Without doubt, there are many who remain highly skeptical of Hamas’s new face, suspecting a ploy to gain power by concealing true agendas. Certainly, the progressive de-emphasis on Islam as revealed in these three documents can be viewed at least partly through an electoral (and post-electoral) lens, showing Hamas’s desire to present itself as a moderate Islamist movement worthy of trust by secular as well as religious Palestinians not only through its programmatic content per se but also by striving to transcend its own partisan constituencies. But it is equally true that the “new” discourse of diluted religious content—to say nothing of the movement’s increasing pragmatism and flexibility in the political domain—reflects genuine and cumulative changes within Hamas. Moreover, if this evolution has been led mainly by the middle ranking leadership (the technocrats and Western-educated elite), with some of the more orthodox elements having reservations about the movement’s “relaxed and semi-secular” platform, there has been no visible internal rift concerning the new direction, which was embraced and advocated by all members of the movement.

This leaves open the question of whether Hamas in power will be able to function practically within the parameters of the peace process as originally agreed to by Israel and the PLO at Oslo, which Hamas had vehemently opposed. But this question may well remain a moot point in light of the dizzying rate of change on the Palestinian ground since the elections and the swearing in of the Hamas-led government. With the ever mounting external pressures on Hamas, in the form both of ceaseless Israeli attacks on the Palestinians to embarrass the government and of United States–led Western cutting of aid to the Palestinian people and efforts to isolate the government, the chances of aborting the natural development of a “new Hamas” appear great. Although it is too soon to know how events will play out, it is this author’s firm belief that the “new Hamas,” if the movement is given time, will be consolidated from its own experience in power, at the forefront of Palestinian politics.

NOTES

1 In this article, the translations of the passages quoted from the first two documents are those of the author, while Hamas’s official translation of the third document is used.

2 Author interview with Hamas official, 30 January 2006