From children’s piggy banks to heirloom gold: Israeli soldiers looting surge in the West Bank

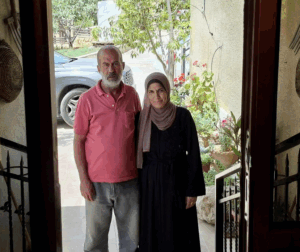

Jihad and Karima Ma’adi in Kafr Malik, July 2025

Amira Hass reports in Haaretz on 7 August 2025:

The aluminum door at the entrance to the Ma’adi family home in Kafr Malik swings open with every light breeze. When a plane flies overhead, it opens wide on its own. “But when the soldiers came on June 6 at four in the morning, it refused to open for them,” said Jihad, 57, the head of the family, in an interview with Haaretz. “I signaled for them to wait until I opened it, but they bent it, broke the glass, and forced their way in.”

He recounted the first moments of the raid – and the story of the capricious door – like a stand-up show, managing to make his guests laugh.

According to the family, beyond the usual damage inflicted during Israel Defense Forces raids – overturned furniture, spilled cabinet contents, including rice and sugar – the soldiers left with loot: approximately 2,000 shekels in cash, a credit card, a 2014 Ford Focus, and gold jewelry. Karima, the mother of the family, said that when the soldiers left around 5:30 a.m., neighbors across the street heard them singing.

This is far from an isolated case. Since late 2023, a growing number of testimonies about confiscations and looting by soldiers in the West Bank have reached human rights organizations such as the Jerusalem Legal Aid and Human Rights Center (JLAC, based in Ramallah) and the Israeli NGO Yesh Din – Volunteers for Human Rights. The true scale is hard to quantify, as not all victims report the incidents, and no single body compiles all complaints filed with either Palestinian authorities or Israeli human rights groups.

If the dominant military perspective is that all Palestinians are terrorists and every raid in the West Bank is framed as a ‘counter-terror operation,’ then every home becomes a presumed terror site.

Still, two indicators are available: According to the PLO’s Negotiations Affairs Department, which documents occupation-related incidents daily, there were 13 reports of property confiscation or theft by soldiers in June 2023. By comparison, in June 2025 – when the Ma’adi family home and others were raided – that number had risen to 62.

Yesh Din, for its part, was aware of eight suspected looting cases between January 2021 and October 2023. Between October 2023 and June 2025, that number grew to 28, according to Dan Owen, a researcher with the organization – though he emphasized that these figures do not represent the full scope of the problem.

Reports describe confiscation or theft of cash, checks, mobile phones, computers, watches, children’s piggy-bank savings, credit cards, gold jewelry, and vehicles. In some cases, soldiers leave behind a form of documentation – a paper Palestinians refer to as a “receipt.” Even then, these forms often omit parts of what was taken.

In many cases, no official pretense is made at all: after the raid, family members – who were held in one room at gunpoint – are released, only to discover that valuables and cash are missing. From Ya’bad in the north to Halhul and Hebron in the south, from refugee camps to private homes and commercial properties, victims describe strikingly similar experiences.

The Ma’adi family, for instance, received official confirmation that 1,500 shekels and a car were seized – and nothing else. The gold jewelry, which was not included on the “receipt” the soldiers left behind, had been given to Karima, 52, by Jihad when they married nearly 30 years ago. Jihad worked most of his life at a village stone-cutting plant, and in recent years opened a small grocery store near their home. Karima has been a schoolteacher in the village for 28 years.

Karima had passed the jewelry down to her daughter-in-law, the wife of her 28-year-old son, Islam. The young woman was heavily pregnant when 12 soldiers stormed the house on June 6.While the soldiers gathered all seven family members into a single room and watched them with rifles drawn, everyone worried about her and her unborn child. The jewelry was hidden inside a purse sewn into the lining of a blanket, within a stack of folded blankets in the youngest daughter’s room.

The used car was bought three years ago for 38,000 shekels. Karima took a bank loan for the purchase, and until around March of this year, a fixed sum was deducted from her salary each month to repay the debt. The car was also meant to help Islam. In addition to working as an accountant for a commercial company in Beitunia (west of Ramallah), Islam had started raising bees. He placed his hives in Bil’in, his wife’s village, known for its diverse plant life.

Moreover, in Kafr Malik and its surroundings, no secure space remained for beekeeping: settlers and their outposts had gradually taken over more and more land, both there and in surrounding villages. In fact, the hives disappeared the one time he placed them a bit farther from home.

Alongside this, Islam also worked as an accountant at a concrete factory in the village of Deir Jarir to the southwest. But when the war in Gaza broke out, the army blocked the main road connecting the two villages. The barrier remains in place to this day. As a result, he now works only in Beitunia. What was once a 15-minute commute to and from Ramallah now takes over an hour via a circuitous route – and even longer by public transportation – due to this roadblock and two others.

Whatever’s Within Reach

June 6 marked the first day of Eid al-Adha, a major Islamic holiday. Islam had received a 1,200-shekel advance from his employer (his monthly salary is 4,200 shekels). He spent 400 shekels on household needs and set aside the remaining 800 for the holiday – until soldiers took it. His mother had 600 shekels and a credit card tucked into her ID card, which soldiers confiscated during the search. The ID was returned – but the money and the card were not. A younger brother had 250 shekels in his room, which was also taken, along with a 50-shekel bill on the television and various coins scattered around the house.

Before leaving, the soldiers ordered Islam to drive his car to the edge of the village, escorted by an army jeep in front and another behind. “‘Why don’t you have a jeep?'” the officer asked me,” Islam recalled. At the village exit, the soldiers told him to get out of the car. The officer shoved a 200-shekel note into his hand and said in Arabic slang, “Make do with this.” Islam then walked the two kilometers back home on foot. When he returned, the family found Karima’s fake gold jewelry strewn across the bedroom floor. They were astonished the soldiers could tell the difference between real and imitation gold.

The family received an official document titled “Notice of Property Seizure” confirming the confiscation. The form is based on the British Mandate-era Emergency Defense Regulations of 1945 and IDF Order 1651 (2009) on security provisions. These orders give soldiers broad free rein to seize anything they claim is linked to a security-related offense – without requiring evidence, judicial oversight, or any limit on the amount or value of goods taken.

Reports of property confiscation and theft by Israeli soldiers have surged, according to the PLO’s Negotiations Affairs Department. In June 2023, the department recorded 13 such incidents; by June 2025, that number had jumped to 62.

This documentation process only began after an April 2016 petition to Israel’s High Court of Justice by the human rights group HaMoked – Center for the Defense of the Individual, which challenged the army’s practice of confiscating Palestinian property without record or recourse. Two weeks before the hearing, in January 2017, the IDF announced a new protocol titled “Searches in Palestinian Homes in the West Bank,” a classified procedure that has yet to be made public.

In recent confiscation cases reported to Haaretz, Yesh Din, and the Jerusalem Legal Aid Center, the soldiers relied on the first clause listed on the seizure form: “Providing service to unlawful association / Receiving funds from an unlawful association / Possession of property belonging to an unlawful association.” A blank section allows soldiers to write – in Hebrew – what items were confiscated. Property owners are required to sign, even if they don’t read Hebrew.

Amjad Atatra, the mayor of Ya’bad, received no documentation for the 2,600 shekels soldiers took from his daughter’s wallet around 2:00 a.m. on June 25. Soldiers had entered the town about four hours earlier, on foot and in vehicles, taking control of three homes, ordering residents to leave, and imposing a curfew. Within 48 hours, they had raided 113 homes.

“From the early hours, we began receiving reports from residents who said they were locked in a room while soldiers searched the house, vandalized property, and stole,” Atatra told Haaretz from his office, which overlooks the Mevo Dotan settlement. After the soldiers left, residents began arriving at city hall to report what was missing.

At least two residents reported gold had disappeared. Others said soldiers stole smartphones – three from one home, four from another. In some cases, soldiers simply smashed the phones. From one home, they took 5,000 shekels. In another, they seized dozens of foreign currency notes and around 1,300 shekels from children’s piggy banks. Another 3,500 shekels – borrowed by a resident to pay for his daughter’s university tuition – vanished, as did 500 shekels from a 60-year-old woman, a 20-shekel bill kept in one of Atatra’s brother’s ID cards, and 300 shekels from a young man taken for questioning in one of the homes converted into a temporary army base. Not a single resident of Ya’bad received a “receipt.”

The New Normal

The ease with which “official” confiscations are carried out – requiring no evidence, justification, or legal process – has led to soldiers essentially privatizing the practice.

“If the army allows me to take people’s money and I don’t have to justify it, then I can just take money. Period,” said attorney Roni Pelli of Yesh Din, summing up the mindset reflected in many of the reports her organization receives. “If they get caught, soldiers can always say they thought it was terror money.”

Pelli notes that the atmosphere of the war in Gaza has clearly influenced soldier behavior in the West Bank as well. She recalls the widespread looting carried out by soldiers in Gaza since late 2023. “Why would they behave differently in the West Bank?”

Breaking the Silence Executive Director Nadav Weiman says that while his organization hasn’t received direct soldiers’ testimonies of theft, it’s clear that “the school most soldiers go through today is Gaza.” The uninhibited behavior there, he adds, “has become the new norm.”

If the dominant military perspective is that all Palestinians are terrorists and every raid in the West Bank is framed as a “counter-terror operation,” then every home becomes a presumed terror site. “So every 50 shekels becomes terror money, fair game for seizure,” Weiman says. “In the South Hebron Hills – where we have a lot of contacts – we constantly hear about soldiers stealing gold chains, for example, or cash.”

In the absence of evidence or clear suspicion, some victims wonder whether the seizures are linked to Israel’s campaign against payments to former Palestinian prisoners. During the First Intifada, Jihad Ma’adi was a Fatah activist and spent one year in Israeli prison – like many thousands of others during that period – a duration that does not qualify for a Palestinian Authority prisoner allowance. His son, Islam, served two years in prison for his involvement with the Islamic student bloc at Birzeit University and was released in 2018. A 2-years’ sentence doesn’t qualify for an allowance, either.

Their neighbor, Ziyad Rustum, 66, served eight years in an Israeli prison for Popular Front activities and was released in 1992. He did receive an allowance of 2,800 shekels from the PA. “Let’s say our money was seized because of that allowance,” Ziyad asked. “Does that mean the Palestinian Authority is an illegal association?”

The army stormed Ziyad’s home around 3:10 A.M. in what has become the standard routine: “pounding on doors downstairs, shouting, rifles pointed at us, 15 soldiers breaking in,” described his 52-year-old wife Carmen. According to the family, the soldiers took over 16,000 shekels but recorded only 10,660 in their documentation.

Of that sum, 8,000 shekels were reserved for the upkeep of a nearby family home whose owners live abroad. Another 1,500 belonged to their son, who works at a local store; 5,000 shekels were their daughter’s salary from an auto parts shop; and 1,200 shekels belonged to their other son, employed at a telecommunications company.

The soldiers also took and recorded Jordanian dinars and two U.S. one-dollar bills – altogether worth around 11,000 shekels. Not recorded in the seizure form were two gold bars, each valued at about 3,200 shekels, as well as an iPhone charger, a credit card, and a power drill. “As they left, the soldiers gave me 200 shekels,” Ziyad said.

This seems to be part of a pattern. In one village, a soldier wrote on a form: “humanitarian 200 shekels – given,” while 800 were seized. In another, the form read: “Leaving 250 shekels.”

Before taking over the home, the soldiers gathered the five Rustum family members into one room. “They didn’t even let us use the bathroom,” Carmen said. Ziyad noted that in the past, soldiers would often take a family member with them during a search to witness that nothing was stolen. But attorney Pelli says she hesitates to suggest that now. “Given the way soldiers are behaving today, it’s not safe to leave a Palestinian alone in a room with them,” she said. She also doubts the usefulness of body cameras. “We know from Israeli police that the cameras always seem to be off precisely when something happens.”

The IDF Spokesperson did not respond to Haaretz’s detailed questions regarding the confiscation process or the use of seized money and property, nor did they respond to specific inquiries about the Ma’adi and Rustum families. However, the IDF did issue a general statement:

“Administrative confiscations of funds and property are carried out only when there is clear intelligence indicating the items are connected to terror activity or used to promote terror. Every confiscation is conducted only after reviewing the intelligence in accordance with relevant legal frameworks. The IDF operates according to the law, including international law.”

In response to questions about the increasing reports of theft and any possible connection to soldier conduct in Gaza, the spokesperson added only:

“When there is suspicion of a criminal offense by IDF forces that warrants investigation, a Military Police investigation is opened.”

This article is reproduced in its entirety