The director who learned from her own series that Israel has already expelled Gazans

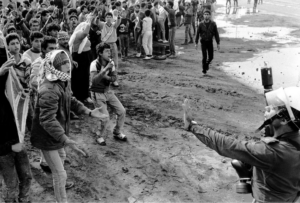

A shot from ‘Gaza Syndrome’

Ido David Cohen writes in Haaretz on 10 February 2025:

“When I got to Gaza, I saw a crowded area: old people, young people, children – they were all terrorists to me. They had to be destroyed; that’s what I thought.” This confession isn’t from the current war. The person who said it on camera is Yitzhak Ini Abadi, Israel’s military governor of Gaza between 1971 and 1973.

Abadi is one of dozens of interviewees – Israelis, Palestinians and Americans – in the documentary “Gaza Syndrome,” whose first of three parts was shown on public television’s Kan 11 on Saturday. And as Abadi’s remarks suggest, Gaza has long loomed large in the Israeli psyche as a threatening, dangerous place.

The series recounts the complex and tragic relationship between Israel and Gaza since Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, when 200,000 Palestinians sought refuge in the enclave. We learn that Israeli occupation fantasies and Palestinian terrorism were both there from the start – and then came the military operations, the wars, the various arrangements and agreements – and an ocean of missed opportunities.

‘Before the series, I was in a sense the average Israeli who says, ‘Wait, we did the disengagement, what do you want from me? I hadn’t realized there was an expulsion of Palestinians into Sinai, that people were taken out of their homes.’ “All our tragic mistakes that got us where we are today,” says Hila Izhaki, who edited and directed the series alongside Duby Kroitoru.

Izhaki says she and Kroitoru aimed to “understand how the Gaza Strip was created and how it came to be a catalyst for the conflict. We Israelis aren’t alone in this story. The Palestinians have also made mistakes, but we can do some introspection: what we tried and what didn’t work over the decades.”

The series explores key events like Israel’s military rule over Gaza for four months after the 1956 Sinai Campaign, and Israel’s first settlement in Gaza, Nahal Rafiah, which was established in 1956 as part of David Ben-Gurion’s dream of a “Third Kingdom of Israel.” We also learn about Menachem Begin’s choice to leave Gaza under Israeli rule rather than try to hand it over to Egypt under the 1979 peace accord, and the secret plan by Levi Eshkol’s government, after the 1967 Six-Day War, to maintain high unemployment in the enclave and “encourage emigration” from Gaza to Arab countries.

Transcripts released over the last decade reveal that in the ’60s, the Israeli government provided “shuttle services” to Jordan for the transfer of several thousand refugees, who received financial compensation. Also, the Israeli military forcefully transferred 38,000 Gazans to Sinai, which was now also under Israeli control after the 1967 war.

A photo which appears in ‘Gaza Syndrome’ showing Gazan youth and Israeli soldiers in 1987 in the Gaza Strip

Prof. Jean-Pierre Filiu, a Paris-based professor of Middle East Studies who appears in the series, calls the uprooting of nearly 10 percent of Gaza’s residents at the time “the second Nakba.”

Izhaki says she didn’t know about this. “Before the series, I was in a sense the average Israeli who says, ‘Wait, we did the disengagement, what do you want from me?” she says, referring to Israel’s pullout from Gaza in 2005. “What’s the problem? I hadn’t realized there was an expulsion of Palestinians into Sinai, that people were taken out of their homes.”

“Gaza Syndrome” shows that the methods employed by Israel over the years may have temporarily quelled terrorism in Gaza, but they have strengthened terrorism elsewhere. And in the long run they have intensified the Palestinian hatred that exploded in two intifadas.

Now, with U.S. President Donald Trump proposing his own crude vision of transfer, a notion that was once merely whispered, Izhaki despairs to see history repeat.

“I think the Palestinians will never agree to such an idea, because they’re as connected to the land as we are,” she says. “And even if some people are happy to leave, the majority will never agree. A transfer is an immoral act banned by international law and could lead us to a regional war.”

Work on the series started two and a half years ago, in the last days of the government under Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid. The initiative came from Kroitoru, the screenwriter and chief editor. Researchers Avi Sofer and Dana Direktor complete the roster.

By early October 2023, Izhaki recalls, around 60 percent of filming for the project had been done. “On October 5, a Thursday, I gave a first draft of the first episode for viewing by the team, and then, a couple of days later, we woke up to October 7. I opened my phone still half asleep and for a few minutes I couldn’t understand what I was seeing. I thought I was seeing archives.”

When things became clearer, “we started calling everybody who had been interviewed for the series. They were relatively okay, as far as you can be okay after such a horrible thing.”

One person who was scheduled but hadn’t yet been interviewed was 84-year-old Oded Lifschitz of Kibbutz Nir Oz, who is still being held hostage by Hamas in Gaza. He is due to be released in the multi-week first stage of the hostage deal underway, but his condition is unknown. “We wanted to talk to him because he was an important political figure, very left-wing, very pro-Gaza Palestinians,” Izhaki says. “In the first few days, I thought we no longer had a series, or we’d have to start working again from scratch, because how can you go on after an event like that? I couldn’t go into the editing room. I couldn’t see this thing.”

Gradually, work resumed. “And then, what was pretty surprising was that the history remained the same. You suddenly realized how we got there. If before October 7 this was a heavy responsibility, it suddenly became an extra heavy responsibility.”

A deep understanding of the medium

Hila Izhaki

Izhaki, 50, married and the mother of two, is used to working behind the scenes. As she restarted work on “Gaza Syndrome” she also worked as a video editor on editions of the “Uvda” investigative news program. This included a story on 9-year-old Emily Hand, who returned from captivity in Gaza, and an interview with Ido and Yonatan Shamriz, brothers of Alon Shamriz, who in December 2023 escaped his captors and was shot dead in Gaza City by Israeli soldiers who mistook him for the enemy.

The intense preoccupation with hostage stories didn’t make things easy for Izhaki. “I edit everything very emotionally,” she says. “Everything is emotional with me, so you argue with yourself, like, ‘Wait a minute, Emily just came back from this horror, so what do I care about the suffering of those people in Gaza?’ Well, not exactly.”

It’s okay to admit this if that’s what you felt.

“At certain moments. It’s not that I said to myself, ‘What do I care,’ but you suddenly look at it differently. We were shooting before all those long months of the war, and suddenly Gaza, this godforsaken place that we always thought we were so strong against, felt like an existential threat.” Izhaki also notes how Direktor, one of the researchers, told her she suddenly realized that all of the Israeli conceptions before October 7 had been shattered – “for example, that we can live alongside Hamas.”

Did you ask to interview Benjamin Netanyahu?

“This ambitious idea never crossed our minds. I can’t believe he would have given an interview to a Kan 11 series about Gaza. He was very supportive of that entity [Hamas]. He probably didn’t invent the doctrine of supporting that extremist entity, but he turned Hamas into an asset, and we also try to show this.”

Netanyahu pops up in the third episode. He is portrayed in part as the person who released Hamas co-founder Ahmed Yassin from prison (following the Mossad’s failed assassination attempt against Hamas leader Khaled Meshal in Jordan in 1997). Netanyahu is also depicted as the person who, in his 2009 election campaign, promised to “crush Hamas’ rule,” while actually he opted for limited military operations that strengthened the group, while shunning any dialogue with the Palestinian Authority.

To Izhaki, Israel’s most glaring mistake for generations is that “we failed to talk to the right people all along the way, and we refused to see them, whether mistakenly or willfully. Not looking for the moderate people to work with – that’s what screams out the most.”

Today it seems there is hardly any debate about incidents where Palestinians are harmed.

“What was lacking in the past and is still lacking is wisdom. Gazans may have been very bad, some were terrorists and some were … refugees, but where is our wisdom? When you make a historical series, you ask, ‘What seeds did I sow back then?’ The child who saw his mother stripped naked in the street; what kind of man will he grow up to be?”

This article is reproduced in its entirety