Why you must watch this lost documentary on the Israeli occupation

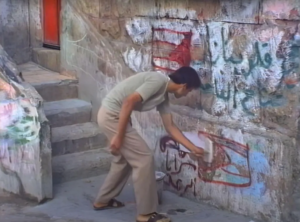

A Palestinian man being forced to paint over graffiti of the Palestinian flag in ‘Reserve Diary Hebron 1989’

Avshalom Halutz reports in Haaretz on 4 November 2024:

The exact time and location were kept under wraps until 24 hours before the event. “Thank you for registering! Please check your phone for updates with more info,” was the cryptic message those who signed up received. An hour before it started, only a discreet, handwritten note in Hebrew – hung on the door of a Tel Aviv apartment block – hinted at what was happening inside: “‘Reserve Diary.’ Third floor.”

It’s hard to fathom that such measures are needed to ensure the safe screening of a short, little-known documentary that was shot more than 35 years ago. But recent incidents in Israel show that nothing can be taken for granted nowadays, and that the freedom to watch anything that might contradict the mainstream Israeli narrative has been greatly diminished.

In October, the Israeli police told the head of a Jaffa theater that they were prohibiting the screening of the documentary “Lyd,” on the Arab-Jewish city of Lod, mere hours before it was supposed to take place. Two months before that, the police closed the offices of left-wing party Hadash in Haifa because of a planned screening of the documentary “Jenin, Jenin,” by Palestinian-Israeli actor-filmmaker Mohammad Bakri.

However, unlike those two films, which generated a lot of headlines, filmmaker Yishai Shuster’s “Reserve Diary, Hebron 1989” (or as it’s known in English, “A Soldier’s Diary: An Israel Reserve Soldier’s Occupation Diary”) is virtually unknown, even among the most occupation-seasoned of Israeli leftists.

Due to pressure from both the Israel Defense Forces and politicians, the documentary has hardly ever been screened domestically – though the old Channel 2 dared to broadcast it, 10 years ago, at the prime time of 2 A.M.

Filmmaker Yishai Shuster, left, Breaking the Silence Executive Director Nadav Weiman, filmmaker Noam Sheizaf and Gali Hendin from Mistaclim, taking part in a panel at the screening of ‘Reserve Diary Hebron 1989’

What’s so dangerous about “Reserve Diary, Hebron 1989” that the powers-that-be don’t want you to see it? Watching the recently digitized version at the special screening in Tel Aviv and hearing the audience’s repeated gasps proved just how effective and relevant it still is today. Despite depicting the occupation as it was in the late 1980s, it shows in great detail the appalling reality that has only deteriorated since.

Assaf Uzan compares “Reserve Diary” to the latter-day work of anti-occupation, ex-soldiers group Breaking the Silence. “It is a soldier’s honest testimony, years before Breaking the Silence started to operate, and totally devoid of filters.”

Prior to being called up for reserve duty at the time, Shuster, now 79, planned to bring a small still camera along with him. His friend, the late director and producer Gideon Gitai, suggested he take a handheld video camera instead in order to document his service, and sorted the equipment out.

From early on in the film, Shuster – who also narrates – does not mince his words. He calls himself a “soldier of occupation,” expresses his disgust at a redhead soldier who randomly shoots at Palestinian children, justifies his opposition to taking part in the occupation and calls the Jewish settlers, whom he ends up guarding 12 hours a day, “settlerrorists.”

In 46 minutes, Shuster and his brilliant film editor, the late Era Lapid, display the occupation in all its ugliness: soldiers everywhere, arbitrary violence against civilians, and the erasure of the Palestinian identity (flags are forcibly removed; citizens are ordered to cover graffiti of the Palestinian flag with white paint).

Shuster’s material is seamlessly integrated with footage taken by a foreign news agency operating in the flash-point West Bank city. After shots of violence and humiliation are seen, the film then focuses on Shuster’s conversations with his fellow Paratroopers Brigade reservists – most of whom are kibbutznikim who oppose the occupation and openly criticize their own presence in Hebron.

There are also encounters Shuster and his fellow soldiers have with children, both Palestinian and Jewish. Seeing small Palestinian children having to grow up surrounded by armed men who can’t speak their language is nothing short of terrifying.

The film would have remained largely hidden had it not been for educator and former journalist Assaf Uzan, who met Shuster a decade ago and learned about the “lost” documentary he had made.

“I remember watching it and being shocked by its authenticity and its open criticism of soldiers policing the Palestinian population,” Uzan tells Haaretz. “At the time, I didn’t think to do anything about it. But several months ago, I suddenly thought about the film, searched for it online and was surprised that it’s not available anywhere. I realized that people haven’t seen it, and how crucial it is that people will be able to watch it and learn about the processes and operations that were documented in it. It’s especially important as a film made by a reservist, without a script – which further highlights its authenticity.”

A scene from Isabel Herguera’s ‘Sultana’s Dream’

Uzan compares “Reserve Diary” to the latter-day work of anti-occupation, ex-soldiers group Breaking the Silence “It is a soldier’s honest testimony, years before Breaking the Silence started to operate, and totally devoid of filters,” he says.

The educator recounts how he got back in touch with Shuster again. “He had never uploaded the film online because he wasn’t sure how to do it, and was also worried about renewed threats and lawsuits against him. He told me he preferred not to get into trouble again – but eventually I managed to persuade him. And now the film is available on YouTube with the help of film editor Shira Arad, and Sigal Shukron from Mistaclim – Looking the Occupation in the Eye, and attracts more and more interest,” Uzan says.

“It’s a moment that distills the whole film and occupation in its entirety into just one look. We all should look in the mirror and see what has happened to us.”

‘Severely reprimanded’

After “Reserve Diary, Hebron 1989” premiered on Finnish TV in 1990 (it was financed by the Finns), it was barely screened in Israel. For a short while, though, it was the subject of much debate in sensationalist articles.

“The Israeli ambassador to Helsinki was informed that the film was about to be screened, so he rushed to send a telegram to the Culture Ministry, warning them of an ‘anti-Israeli’ and ‘anti-IDF’ film,” Shuster recalls, speaking from his home in Yad Hana, a central Israeli kibbutz near the border with the West Bank.

“It reached then-Prime Minister Yizhak Shamir, who sent a letter to the then-Deputy Chief of Staff, Ehud Barak. I saw that letter. Shamir demanded that the army find this soldier and deal with him severely. Eventually, I was told that I didn’t do anything illegal and only committed a disciplinary offense, because a soldier is not allowed to film during his service – in complete contrast to what we see nowadays [in Gaza and the West Bank]. I was severely reprimanded, but only because I refused to say I felt sorry for what I did.”

While the documentary was effectively buried in Israel, it was seen in a different light elsewhere. “I presented the film at a Jewish film festival in Toronto, where the audience was mainly peace activists and university professors,” Shuster notes. “I told them that I got criticized and judged for the film. And they were shocked – they found the film to be pro-IDF. They said: ‘We read about people like that nasty redhead soldier and the violence shown at the beginning of the film, and you then show a different side of the army. A nicer side. Of soldiers who oppose the occupation and dare to speak about it.”

The recent screening, organized by several left-wing organizations, included an insightful talk by filmmaker Noam Sheizaf (who, together with Idit Avrahami, made the 2022 documentary about Hebron’s Tomb of the Patriarchs, “H2: The Occupation Lab”). It was followed by a panel discussion on documenting the occupation, moderated by Sheizaf, with director Shuster, Breaking the Silence Executive Director Nadav Weiman and Gali Hendin from Mistaclim.

One of the first things Shuster said on stage was: “If I were in my 40s now, seeing what is going on in Israel – I would have left.”

Shuster films encounters he and his fellow soldiers have with children, both Palestinian and Jewish, in the film.Credit: Screenshot/Yishai Shuster

Weiman, like most of the audience, was watching the documentary for the first time. He has led tours of Hebron for more than a decade and said he was surprised by two things: “I have never seen the streets of Hebron so filled with Palestinians. Nowadays, it’s a dead city. I was truly amazed by that. And the second thing is that I remember having conversations with fellow soldiers during my military service and thinking: We’re the first moral soldiers. And in the film you see soldiers saying the exact same things, decades earlier.”

A short scene toward the end of the documentary – which was shot without Shuster realizing the camera was on – helps make the film so powerful. Shuster, the leftist filmmaker who hates his reservist duty and feels bad for the Palestinians, can be heard ordering Palestinian merchants, whose scared faces are being filmed, to remove their goods from the side of the street. He talks to them in an especially demeaning manner, shouting and threatening in a heavy Israeli accent.

Shuster didn’t want to include that sequence in the film, but editor Lapid and producer Gitai persuaded him otherwise. “And I thank them for that,” he says now. “In that segment, you see that there’s no such thing as an enlightened occupation, or ‘occupation-lite.’ An occupation is an occupation. It’s a violent thing. It’s a disgusting thing that managed to corrupt everyone, including me.”

For Uzan, that climactic scene is the film’s defining moment – “when Yishai the reservist who is here to document becomes the subject, and suddenly gets to see himself. It shows how even a critical and reflective person can turn into a belligerent being, devoid of human sensitivity.

“Everything is reduced to one stare, as Yishai sees himself reflected in the Jeep’s mirror. The helmet, the sunglasses, the unshaven beard after 23 days’ service. We see him – but above all he sees himself. It’s a moment that distills the whole film and occupation in its entirety into just one look. We all should look in the mirror and see what has happened to us.”

I asked Shuster how it was for him to watch the movie again now. “Intuitively, I wanted to say a yearning,” he surprises me. “A yearning for the Israel that once was. These were the days before Rabin took office, before the Oslo Accords. There was some hope in the air. The occupation existed, and I show it in all its ugliness, but I miss those days when we still had hope for change.”

How to document a war

The screening of “Reserve Diary, Hebron 1989” wasn’t the only recent event on the subject of documenting the conflict. Hundreds of people attended the conference “A Year of Destruction: Documenting the War,” organized by the Peace Partnership and news site Local Call at Tel Aviv’s Radical House. The event’s goal was to discuss efforts to gather testimonies from the current war and to document the unimaginable horrors that the Israeli media doesn’t dare show.

The opening panel, called “The Evidence Recorders,” moderated by Solafa Makhoul from the Peace Partnership and Noa Levy from the Hadash party, brought together several leading activists, documentarists and scholars. They discussed their efforts to document and report on the war’s atrocities while operating in a general climate of hate and indifference.

Sarai Aharoni talked about how to treat testimonies of sexual assault victims. Photographer activist Oren Ziv, who uses his camera to record the occupation, talked about his work. Mauricio Lapchik from Peace Now discussed tracking the alarming acceleration of new government-backed settlements and outposts in the West Bank.

Others discussed the huge amount of footage being shot by the police and the army, and the questions surrounding its use, and the meaning of documenting in an era of social media, with the influx of videos created by soldiers sharing their own actions.

The second part of the conference included live and filmed testimonies. The live testimony of Palestinian-Israeli lawyer Sari Huria from Haifa, who was jailed in Israel and experienced humiliation and detailed the horrible abuse of other men he witnessed, was especially powerful. His only sin, by the way, was posting against the occupation on Facebook. His arrest resulted in the Israeli media portraying him as a Hamas affiliate. His speech was followed by the recorded testimony of a Gazan man who fled to London after experiencing unbearable suffering during the war.

There was also a live testimony by veteran peace activist Yaacov Godo, whose son Tom was murdered on October 7, 2023. He talked about how Tom protected his wife and small children during an attack on their home in Kibbutz Kissufim, but was eventually killed by terrorists. “Not one member of the government has contacted us since,” he told the attendees. “The only official Israeli organization that reached out was Chevra Kadisha. They called me to ask where I want my son to be buried.”

Celebrating queer freedom while ignoring Gaza

Last week saw the opening of TLVFest, the queer film festival that celebrates its 19th edition this year at Tel Aviv’s Cinematheque and runs until November 10.

While many in the global LGBTQI+ community take an active part in the demonstrations against Israel’s mass killings in Gaza, the local queer community remains largely confused about its role. The same can be said about the festival, which has chosen to continue to look inward, concentrating instead on the important queer rights and not extending the fight beyond that.

As with other recent Israeli festivals, this edition includes a selection of films related to October 7. One of those films was Adam Kalderon’s 2014 drama “Marzipan Flowers,” which was shot on Kibbutz Be’eri in 2012 and is inspired by the diaries of his mother, Rotem. She was murdered by Hamas terrorists in the same kibbutz on October 7. All proceeds from the screening went toward the rebuilding efforts at Be’eri.

Are there any Palestinian films this year? “Uh, hang on, let me check,” says Gili Porat, who is in charge of the short international films program. “We have a queer film from Bhutan! And one of the judges in the shorts category is Palestinian. Let me look. We have a film from Iran. You know, most Palestinian filmmakers don’t want to take part in an Israeli festival. It’s always difficult and every year we deal with BDS – but this year it’s particularly hard.

“On the other hand, the entire program is also in Arabic and we give free tickets to queer Palestinians who can’t afford them,” Porat adds. “We also have special screenings in Jaffa. I’m sure that many will choose to talk about the war in their speeches.”

Yet despite their best efforts, the festival won’t hold any specific event to discuss the ongoing carnage in Gaza, with the organizers seemingly preferring to focus only on their own struggle and not take a clear stance on the war.

This article is reproduced in its entirety