Beyond a fringe: JVL in Jewish Experience and Tradition

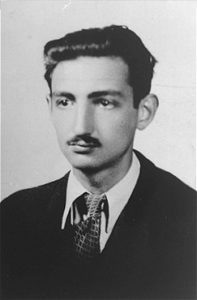

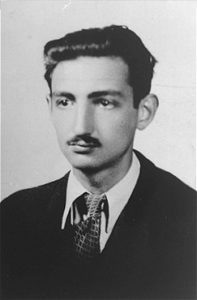

Three-outstanding-actiivits-Vladimir-Medem-Clara-Lemlich-Marek-Edelman

Murray Glickman writes about the history of Jewish socialism and trade unionism that was part of the Bundist philosophy of making common cause with progressive forces in the wider society to improve the lot of all oppressed groups. The Bundist philosophy is alive today in Jewish Voice for Labour and more widely in Jewish culture.

Murry is a long-standing member of Jews for Justice for Palestinians and of JFJFP’s Lobby Group.

Introduction

Jewish socialists have ‘dissident’ views, by mainstream standards. For all that, our formative ideas are rooted in the Jewish experience and in Jewish cultural tradition. We are not ‘dissident Jews’ but ‘dissidents and Jews’. I’d even go so far as to suggest that we are dissidents because we are Jews. This is what I aim to show in the discussion that follows.

Diaspora

Jews have been an identifiable ethnic/religious group for close to two millennia, perhaps longer. During that time and for as long as the historical record exists, we have been a diaspora. By that I mean, we have lived all that time in geographically separated communities spread across different continents. Whether, originally, we were or were not scattered deliberately by imperial decree is not a question I need to go into. The points that matter are, first, that Jews have always lived in communities dispersed across different countries and, second, that in those countries they have always lived as an ethno-religious minority socially distinct from the rest of the population.

Jews are not only part of a border-straddling diaspora; they are very conscious of the fact. As a result, they have traditionally looked with suspicion and distrust on the narrow ethno-nationalistic attitudes that have emerged periodically within majority communities among whom they have lived.

This is not difficult to understand. As Jews, we find out at an early age that there are people in other countries — Jewish and non-Jewish — who are human beings just like us. furthermore, we are in no doubt that any xenophobia arising in the wider community within which we live can as easily turn against us as against ‘foreigners’ elsewhere. That serves as some kind of check on Jews readily identifying with nationalistic waves that may sweep through the community outside. To that extent, our Jewish experience cautions us against chauvinism and inclines us towards a view of the world that looks beyond the ‘nation’. Consciousness of being part of a diaspora can be salutary in moral, humanistic terms.

Oppression

A concomitant of diaspora has been oppression. It did not have to be like that. It is certainly not like that in Britain in 2021. But that is how it has been for most of Jewish history.

For the far-right today the internet is a ‘safe space’ from which to spread antisemitic hate. But as poisonous as they are, their outpourings do not bear mention in the same breath as the experience of inescapable hatred, contempt and prejudice endured by Jews of past generations. Furthermore, the core of the oppression that Jews have suffered has lain not in what was said to them or written about them but in the material mistreatment inflicted on them. Denial of basic rights has been the norm: violence, confiscation and expulsion have been dismally regular occurrences.

Spatially and socially segregated and all but powerless, Jews nevertheless had to engage with external political authority. A glimpse into what this meant in the seventeenth-century in the region around Hamburg is offered in the diaries of Glikl fun Hameln [Glückel of Hameln – Wikipedia]. In these, Glikl — a merchant’s wife and exceptionally rare as an educated female — provides a vivid picture of her family life. She also records the recurrent experience of unequal, often unsuccessful, negotiation with local rulers that Jews of her community had to undertake simply in order to live, work and trade where they needed to be.

The cultural impact on Jews of this existence has been significant. Long-term experience of asymmetric relationships with alien political authority has fostered an impulse among Jews to empathise with, and reach out to, others in the same position. More than that, long practice in engaging with hostile power in adverse circumstances has become a kind of cultural ‘capital’ that Jews can draw on to help others fight oppression strategically.

As Jewish socialists, we embrace this tradition wholeheartedly and do all we can to continue it.

Out of the (European) ghetto

Patchily, in limited fashion and with many reverses, Jews began to acquire civic rights in many parts of Europe in the nineteenth century, starting with the reforms of the Napoleonic era. Rapid economic change assisted the process. Europe’s ghetto walls began to come down. These developments are part of the ancestral history of most JVL members, and the discussion which follows largely focuses on consequences of them. For that reason it is euro- and Ashkenazi-centric. Here I must admit my ignorance of the Mizrachi and Sephardi experience, but I am sure there is a parallel story to be told.

Judaism has traditionally prized learning and literacy (at least for males), though strictly for religious purposes. This had the result that a relatively large number of Jews received what was in effect a training in logical inference and close study of texts. From this cultural springboard, many ninetieth-century European Jews were quick to take advantage of any easing of restrictions to venture into the expanding spheres of secular, ‘gentile’ knowledge and related activity. There was even a ‘Jewish Enlightenment’ movement — the Haskalah.

The scientific outlook and ideas of rationalism, liberalism, humanism and the ‘Rights of Man’ found a ready audience in Jewish circles. This was due in large part — there can be little doubt — to prior Jewish experience of oppression. It is also true that, as excluded outsiders, Jews were not socially conditioned into ready acceptance of modes of thought deriving from the past that prevailed within the population as a whole.

For present purposes, a key development in nineteenth-century social thinking was that political emancipation became conceivable as a goal for which society’s lower ranks could strive. Jews, of course, fell predominantly into that category.

The Bund

Increasing social access led to large-scale Jewish engagement in social and humanitarian movements. My concern here is with just one such development, the rise of the Bund — or to give it its full title, the Jewish Labour Bund.

By the late nineteenth century, impatience for change, working-class consciousness and radical ideas were sweeping European society as a whole and having a major impact in the Jewish world in particular.

For reasons such as those already outlined, Jews were attracted to socialist ideas of all kinds. A key development was the foundation, in 1897, of the Jewish Labour Bund. At that time, a large majority of the world’s Jews lived in northern and eastern Europe. The Bund was created by and for this increasingly urbanised population. At the same time, the late nineteenth and early years of the twentieth century was also a period of mass emigration for East European Jews. The favoured destination was the USA.

The Bund, meanwhile, grew to become a dominant influence in Jewish political life in inter-war Poland and other parts of eastern Europe. Published estimates of the distribution of the world’s Jewish population for 1939 underline the significance of this. By then, mass emigration was long over. Yet, even at that late point, 45 per cent of the world’s Jews lived in Poland, the USSR (including the Baltic regions) and Romania — areas loosely corresponding to what had been the Pale of Settlement. 19 per cent still lived in Poland alone. By contrast, Jews living in Asia, North Africa, Greece, Italy and European Turkey (loosely, the Sepharad and Mizrach) together accounted for only 9 per cent of the total.

it is also worth noting that the vast majority of Jews living in Britain today are descendants of this immigration wave. Jewish socialists and trade unionists took their ideas — including their Bundist ideas — with them wherever they went (see, for example, the case of Clara Lemlich in the US). Their settlement in Britain coincided with the emergence of our Labour Party and trade unions as a major political force, a development to which these immigrants and their children made a significant contribution.

Clara Lemlich has left an indelible mark on the United States as a notable Jewish, female, labor activist

The Bundist view

The essential insight of Bundism is that the well-being of the Jewish population of any country is inseparably bound up with the well-being of that country’s population as a whole; in other words, that working for a better society and for the liberation of all citizens was the only way to achieve the emancipation of Jewish citizens in particular.

Out of this came the distinctive Bundist concept of ‘do’igkeyt’ [Yiddish, ‘hereness’]. This is powerfully expressed in the following statement by Vladimir Medem, Bund leader in 1920:

“[Zionists] speak of a national home in Erets Yisroel, but our organization opposes this thinking absolutely. We believe our home is here, in Poland, in Russia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and the United States.

Here we live, here we struggle, here we build, here we hope for a better future. We do not live here as aliens. Here we are at home! It is on this principle that our survival depends.”

[The text appeared in the journal, Di Naye Velt (2 July 1920, p. 12), quoted in Arthur Neslen, Occupied Minds, (Pluto Press, 2006)]

A traumatic century on, these words continue to inspire.

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York City killed 146 workers,

Ethical and religious dimensions

Over a century or more, religion has waned in importance for Britain’s Jews, mirroring changes in society as a whole. But Christian ethical ideas remain embedded in British culture as —I would argue — do Jewish ethical ideas amongst Britain’s Jews. And, of course, the ethical ideas of the two religions have close historical linkages.

Most members of JVL are secular in outlook: A large number have energetically thrown out the scriptural bathwater. But many of us nevertheless have taken care not to throw out the ethical ‘baby’ at the same time. Others, it seems to me, give this baby a place whilst not necessarily appreciating its parentage.

The Bundist generations embraced secularity, like numerous other Jewish contemporaries. Yet many did so from a position of deep familiarity with the Jewish religion and consciously retained what they found good in it. They built on and out of religious tradition rather that abandoning it totally. In this and many other ways, I believe, traditional Jewish ethical thinking continued to be a salient influence on Jewish socialists thereafter.

An outstanding example of this is the Bundist invention of the secular ‘Seder’.

Traditionally, the first two nights of Passover are given over to the formal Seder service and meal. During it, the story of the Exodus is told and, within it, the role of divine providential intervention is emphasised. The core of the story is one of liberation from suffering and oppression. This is a theme which lent itself readily to reinterpretation reflecting Bundist concerns in the here-and-now. And so, having taken part in the formal Seder at he beginning of Passover, Bundists held their own secular Seders later in the Passover week. At these gatherings, themes of political liberation took centre-stage. One such is described here.

In modern times, this Bundist tradition has been the inspiration for the ‘liberation Seders’ based around myriad liberation themes and held in many parts of the world during Passover. Google came up with nearly 4500 results for “liberation Seder” when I searched this term.

To illustrate further the influence of traditional Jewish ethics on the attitudes of politically progressive Jews, I go on to highlight some passages drawn from explicitly religious sources.

To begin with, Deuteronomy (Dvorim) 10:19, which is typical of many passages to be found in the Pentateuch (Chumesh). It reads:

You shall love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

One doesn’t need to believe the Exodus story is history to appreciate the powerful message this verse sends to members of a now relatively comfortable group for whom awareness of centuries of being the hated ‘stranger’ remains painful and raw.

The Charedi community set great store by the following passage from Jeremiah(Yirmiyohu) [29:7]:

And seek the peace of the city where I have exiled you and pray for it to the Lord, for in its peace you shall have peace.

Again, one doesn’t need to believe that we live in ‘exile’ in the UK today to appreciate the underlying wisdom of the verse. It is not a million miles from the Jewish socialist insight mentioned earlier, that our wellbeing as a minority is inextricably bound up with the wellbeing of the country as a whole.

A final passage I will quote is known as Hiilel’s Golden Rule :

“What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow: this is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.”

One JVL member recently told me that he was taught this maxim in religious classes as a youngster and that it left a lasting impression. He is not the only one to cherish this saying.

In the past, Jews in general spent their lives fervently hoping for the Messiah (Meshiach) to come, redeem the Jewish people and usher in an era of peace and plenty for the whole of humanity. This hope gave solace over centuries of persecution and helped fortify Jews to endure the struggle for life in a hostile world. For Orthodox Jews, this wait remains a key component of existence.

The influence of this patient waiting on secular Jewish socialists should not be overlooked. We can conceive of a much better world than the one we inhabit now, and we hold on to the hope of achieving it.

Concluding synthesis

As its website masthead, JVL proudly cites the following quotation:

“To be a Jew means always being with the oppressed, never with the oppressors.”

Marek_Edelman, leader of the Warsaw_Ghetto_Uprising

These are the words of Marek Edelman, a Bundist who was a leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 1943 and who survived into old age, living and working in Poland. To my mind, they synthesise the values Jews have learned from their diaspora existence, from centuries of exclusion, persecution, expulsion and ultimately from genocide. It should be noted also that the sentiment expressed aligns with the moral teachings of our ancestral religion just as much as it reflects progressive, humanistic modes of thought that have flowered in societies in which Jews have lived over long centuries.

Postscript

With apologies to the creators of the stellar 1960s satirical review, the title Beyond A Fringe alludes to the contemptible demand made of candidates in the 2020 Labour-Party leadership election by the Board of Deputies of British Jews. This was that all the candidates should pledge themselves:

to engage with the Jewish community via its “main representative groups and not through fringe organisations” such as Jewish Voice for Labour.

Hard data do not exist, but all the indications are that the Board is entitled to claim to be ‘deputed’ by 30 per cent of British Jews at the very most. They are in fact a lobby group, no more and no less.

A demand of this kind has no place in democratic politics. But, apart from pointing to it as a backhanded acknowledgment of JVL’s important role, there is something else we can say as Jews. Being ostracised by powerful non-Jewish institutions is nothing new in our history. However, for a Jewish organisation to lead the attack on fellow Jews seems unprecedented. The values we Jews have learned from the oppression our ancestors endured include those of respecting and upholding the rights of others, tolerance and the prizing of open debate and free expression of opinion. In JVL, we hold these values dear because, as I hope I have shown, our roots in Jewish experience are deep and strong. In that, we are clearly beyond a fringe. By the same token, the rejection of these values by the Deputies of the Board is inherent in their conduct towards the Labour Party; in terms of Jewish values, it places them well and truly on the fringe.

Beyond a fringe: JVL in Jewish Experience and Tradition

Three-outstanding-actiivits-Vladimir-Medem-Clara-Lemlich-Marek-Edelman

Murray Glickman writes about the history of Jewish socialism and trade unionism that was part of the Bundist philosophy of making common cause with progressive forces in the wider society to improve the lot of all oppressed groups. The Bundist philosophy is alive today in Jewish Voice for Labour and more widely in Jewish culture.

Murry is a long-standing member of Jews for Justice for Palestinians and of JFJFP’s Lobby Group.

Introduction

Jewish socialists have ‘dissident’ views, by mainstream standards. For all that, our formative ideas are rooted in the Jewish experience and in Jewish cultural tradition. We are not ‘dissident Jews’ but ‘dissidents and Jews’. I’d even go so far as to suggest that we are dissidents because we are Jews. This is what I aim to show in the discussion that follows.

Diaspora

Jews have been an identifiable ethnic/religious group for close to two millennia, perhaps longer. During that time and for as long as the historical record exists, we have been a diaspora. By that I mean, we have lived all that time in geographically separated communities spread across different continents. Whether, originally, we were or were not scattered deliberately by imperial decree is not a question I need to go into. The points that matter are, first, that Jews have always lived in communities dispersed across different countries and, second, that in those countries they have always lived as an ethno-religious minority socially distinct from the rest of the population.

Jews are not only part of a border-straddling diaspora; they are very conscious of the fact. As a result, they have traditionally looked with suspicion and distrust on the narrow ethno-nationalistic attitudes that have emerged periodically within majority communities among whom they have lived.

This is not difficult to understand. As Jews, we find out at an early age that there are people in other countries — Jewish and non-Jewish — who are human beings just like us. furthermore, we are in no doubt that any xenophobia arising in the wider community within which we live can as easily turn against us as against ‘foreigners’ elsewhere. That serves as some kind of check on Jews readily identifying with nationalistic waves that may sweep through the community outside. To that extent, our Jewish experience cautions us against chauvinism and inclines us towards a view of the world that looks beyond the ‘nation’. Consciousness of being part of a diaspora can be salutary in moral, humanistic terms.

Oppression

A concomitant of diaspora has been oppression. It did not have to be like that. It is certainly not like that in Britain in 2021. But that is how it has been for most of Jewish history.

For the far-right today the internet is a ‘safe space’ from which to spread antisemitic hate. But as poisonous as they are, their outpourings do not bear mention in the same breath as the experience of inescapable hatred, contempt and prejudice endured by Jews of past generations. Furthermore, the core of the oppression that Jews have suffered has lain not in what was said to them or written about them but in the material mistreatment inflicted on them. Denial of basic rights has been the norm: violence, confiscation and expulsion have been dismally regular occurrences.

Spatially and socially segregated and all but powerless, Jews nevertheless had to engage with external political authority. A glimpse into what this meant in the seventeenth-century in the region around Hamburg is offered in the diaries of Glikl fun Hameln [Glückel of Hameln – Wikipedia]. In these, Glikl — a merchant’s wife and exceptionally rare as an educated female — provides a vivid picture of her family life. She also records the recurrent experience of unequal, often unsuccessful, negotiation with local rulers that Jews of her community had to undertake simply in order to live, work and trade where they needed to be.

The cultural impact on Jews of this existence has been significant. Long-term experience of asymmetric relationships with alien political authority has fostered an impulse among Jews to empathise with, and reach out to, others in the same position. More than that, long practice in engaging with hostile power in adverse circumstances has become a kind of cultural ‘capital’ that Jews can draw on to help others fight oppression strategically.

As Jewish socialists, we embrace this tradition wholeheartedly and do all we can to continue it.

Out of the (European) ghetto

Patchily, in limited fashion and with many reverses, Jews began to acquire civic rights in many parts of Europe in the nineteenth century, starting with the reforms of the Napoleonic era. Rapid economic change assisted the process. Europe’s ghetto walls began to come down. These developments are part of the ancestral history of most JVL members, and the discussion which follows largely focuses on consequences of them. For that reason it is euro- and Ashkenazi-centric. Here I must admit my ignorance of the Mizrachi and Sephardi experience, but I am sure there is a parallel story to be told.

Judaism has traditionally prized learning and literacy (at least for males), though strictly for religious purposes. This had the result that a relatively large number of Jews received what was in effect a training in logical inference and close study of texts. From this cultural springboard, many ninetieth-century European Jews were quick to take advantage of any easing of restrictions to venture into the expanding spheres of secular, ‘gentile’ knowledge and related activity. There was even a ‘Jewish Enlightenment’ movement — the Haskalah.

The scientific outlook and ideas of rationalism, liberalism, humanism and the ‘Rights of Man’ found a ready audience in Jewish circles. This was due in large part — there can be little doubt — to prior Jewish experience of oppression. It is also true that, as excluded outsiders, Jews were not socially conditioned into ready acceptance of modes of thought deriving from the past that prevailed within the population as a whole.

For present purposes, a key development in nineteenth-century social thinking was that political emancipation became conceivable as a goal for which society’s lower ranks could strive. Jews, of course, fell predominantly into that category.

The Bund

Increasing social access led to large-scale Jewish engagement in social and humanitarian movements. My concern here is with just one such development, the rise of the Bund — or to give it its full title, the Jewish Labour Bund.

By the late nineteenth century, impatience for change, working-class consciousness and radical ideas were sweeping European society as a whole and having a major impact in the Jewish world in particular.

For reasons such as those already outlined, Jews were attracted to socialist ideas of all kinds. A key development was the foundation, in 1897, of the Jewish Labour Bund. At that time, a large majority of the world’s Jews lived in northern and eastern Europe. The Bund was created by and for this increasingly urbanised population. At the same time, the late nineteenth and early years of the twentieth century was also a period of mass emigration for East European Jews. The favoured destination was the USA.

The Bund, meanwhile, grew to become a dominant influence in Jewish political life in inter-war Poland and other parts of eastern Europe. Published estimates of the distribution of the world’s Jewish population for 1939 underline the significance of this. By then, mass emigration was long over. Yet, even at that late point, 45 per cent of the world’s Jews lived in Poland, the USSR (including the Baltic regions) and Romania — areas loosely corresponding to what had been the Pale of Settlement. 19 per cent still lived in Poland alone. By contrast, Jews living in Asia, North Africa, Greece, Italy and European Turkey (loosely, the Sepharad and Mizrach) together accounted for only 9 per cent of the total.

it is also worth noting that the vast majority of Jews living in Britain today are descendants of this immigration wave. Jewish socialists and trade unionists took their ideas — including their Bundist ideas — with them wherever they went (see, for example, the case of Clara Lemlich in the US). Their settlement in Britain coincided with the emergence of our Labour Party and trade unions as a major political force, a development to which these immigrants and their children made a significant contribution.

Clara Lemlich has left an indelible mark on the United States as a notable Jewish, female, labor activist

The Bundist view

The essential insight of Bundism is that the well-being of the Jewish population of any country is inseparably bound up with the well-being of that country’s population as a whole; in other words, that working for a better society and for the liberation of all citizens was the only way to achieve the emancipation of Jewish citizens in particular.

Out of this came the distinctive Bundist concept of ‘do’igkeyt’ [Yiddish, ‘hereness’]. This is powerfully expressed in the following statement by Vladimir Medem, Bund leader in 1920:

“[Zionists] speak of a national home in Erets Yisroel, but our organization opposes this thinking absolutely. We believe our home is here, in Poland, in Russia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and the United States.

Here we live, here we struggle, here we build, here we hope for a better future. We do not live here as aliens. Here we are at home! It is on this principle that our survival depends.”

[The text appeared in the journal, Di Naye Velt (2 July 1920, p. 12), quoted in Arthur Neslen, Occupied Minds, (Pluto Press, 2006)]

A traumatic century on, these words continue to inspire.

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York City killed 146 workers,

Ethical and religious dimensions

Over a century or more, religion has waned in importance for Britain’s Jews, mirroring changes in society as a whole. But Christian ethical ideas remain embedded in British culture as —I would argue — do Jewish ethical ideas amongst Britain’s Jews. And, of course, the ethical ideas of the two religions have close historical linkages.

Most members of JVL are secular in outlook: A large number have energetically thrown out the scriptural bathwater. But many of us nevertheless have taken care not to throw out the ethical ‘baby’ at the same time. Others, it seems to me, give this baby a place whilst not necessarily appreciating its parentage.

The Bundist generations embraced secularity, like numerous other Jewish contemporaries. Yet many did so from a position of deep familiarity with the Jewish religion and consciously retained what they found good in it. They built on and out of religious tradition rather that abandoning it totally. In this and many other ways, I believe, traditional Jewish ethical thinking continued to be a salient influence on Jewish socialists thereafter.

An outstanding example of this is the Bundist invention of the secular ‘Seder’.

Traditionally, the first two nights of Passover are given over to the formal Seder service and meal. During it, the story of the Exodus is told and, within it, the role of divine providential intervention is emphasised. The core of the story is one of liberation from suffering and oppression. This is a theme which lent itself readily to reinterpretation reflecting Bundist concerns in the here-and-now. And so, having taken part in the formal Seder at he beginning of Passover, Bundists held their own secular Seders later in the Passover week. At these gatherings, themes of political liberation took centre-stage. One such is described here.

In modern times, this Bundist tradition has been the inspiration for the ‘liberation Seders’ based around myriad liberation themes and held in many parts of the world during Passover. Google came up with nearly 4500 results for “liberation Seder” when I searched this term.

To illustrate further the influence of traditional Jewish ethics on the attitudes of politically progressive Jews, I go on to highlight some passages drawn from explicitly religious sources.

To begin with, Deuteronomy (Dvorim) 10:19, which is typical of many passages to be found in the Pentateuch (Chumesh). It reads:

You shall love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

One doesn’t need to believe the Exodus story is history to appreciate the powerful message this verse sends to members of a now relatively comfortable group for whom awareness of centuries of being the hated ‘stranger’ remains painful and raw.

The Charedi community set great store by the following passage from Jeremiah(Yirmiyohu) [29:7]:

And seek the peace of the city where I have exiled you and pray for it to the Lord, for in its peace you shall have peace.

Again, one doesn’t need to believe that we live in ‘exile’ in the UK today to appreciate the underlying wisdom of the verse. It is not a million miles from the Jewish socialist insight mentioned earlier, that our wellbeing as a minority is inextricably bound up with the wellbeing of the country as a whole.

A final passage I will quote is known as Hiilel’s Golden Rule :

“What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow: this is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.”

One JVL member recently told me that he was taught this maxim in religious classes as a youngster and that it left a lasting impression. He is not the only one to cherish this saying.

In the past, Jews in general spent their lives fervently hoping for the Messiah (Meshiach) to come, redeem the Jewish people and usher in an era of peace and plenty for the whole of humanity. This hope gave solace over centuries of persecution and helped fortify Jews to endure the struggle for life in a hostile world. For Orthodox Jews, this wait remains a key component of existence.

The influence of this patient waiting on secular Jewish socialists should not be overlooked. We can conceive of a much better world than the one we inhabit now, and we hold on to the hope of achieving it.

Concluding synthesis

As its website masthead, JVL proudly cites the following quotation:

“To be a Jew means always being with the oppressed, never with the oppressors.”

Marek_Edelman, leader of the Warsaw_Ghetto_Uprising

These are the words of Marek Edelman, a Bundist who was a leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 1943 and who survived into old age, living and working in Poland. To my mind, they synthesise the values Jews have learned from their diaspora existence, from centuries of exclusion, persecution, expulsion and ultimately from genocide. It should be noted also that the sentiment expressed aligns with the moral teachings of our ancestral religion just as much as it reflects progressive, humanistic modes of thought that have flowered in societies in which Jews have lived over long centuries.

Postscript

With apologies to the creators of the stellar 1960s satirical review, the title Beyond A Fringe alludes to the contemptible demand made of candidates in the 2020 Labour-Party leadership election by the Board of Deputies of British Jews. This was that all the candidates should pledge themselves:

to engage with the Jewish community via its “main representative groups and not through fringe organisations” such as Jewish Voice for Labour.

Hard data do not exist, but all the indications are that the Board is entitled to claim to be ‘deputed’ by 30 per cent of British Jews at the very most. They are in fact a lobby group, no more and no less.

A demand of this kind has no place in democratic politics. But, apart from pointing to it as a backhanded acknowledgment of JVL’s important role, there is something else we can say as Jews. Being ostracised by powerful non-Jewish institutions is nothing new in our history. However, for a Jewish organisation to lead the attack on fellow Jews seems unprecedented. The values we Jews have learned from the oppression our ancestors endured include those of respecting and upholding the rights of others, tolerance and the prizing of open debate and free expression of opinion. In JVL, we hold these values dear because, as I hope I have shown, our roots in Jewish experience are deep and strong. In that, we are clearly beyond a fringe. By the same token, the rejection of these values by the Deputies of the Board is inherent in their conduct towards the Labour Party; in terms of Jewish values, it places them well and truly on the fringe.