We can't all be Charlie Hebdo

This posting has these items:

1) Junkee: The Problem With #JeSuisCharlie those outside who assert ‘Je suis Charlie’ know little of the French insistence on separation of church and state and the taboo against bringing religion into politics;

2) LRB blog: Moral Clarity, Adam Shatz says that declaring ‘Je suis Charlie’ allows the West to feel innocent again;

3) Pandaemonium: Is there something about Islam?, Kenan Malik points out that all religions have their inhuman activists. If secularists want to understand they must put aside their cynicism and bigotry;

4) Vox: What everyone gets wrong about Charlie Hebdo and racism, Max Fisher says that to get the point of Charlie Hebdo’s you have to be familiar with the nature of French racism;

5) Mediapart: On Charlie Hebdo: A letter to my British friends, in his blog, Olivier Tonneau warns against confusing religion – a fit subject for mockery – with race, which is not.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2925588/002485946.0.jpg)

A racist and Islamophobic portrayal of the Obamas as the front cover of the New Yorker, 2008? See Vox article.

The Problem With #JeSuisCharlie

By Chad Parkhill, Junkee

January 09, 2015

In the wake of the armed attack by self-proclaimed Islamic fundamentalists on the headquarters of the satirical French newspaper Charlie Hebdo, which left ten of its staff and two policemen dead, a global solidarity movement has spontaneously emerged across social media, grouped under the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie.

The hashtag translates from the French as “I am Charlie”, and its thrust is pretty straight-forward: after a cowardly act of political violence, our freedom of speech needs to be vigorously defended, and the best way to do this is to propagate the irreverent, satirical message of Charlie Hebdo – to the extent that Index on Censorship have even called for publishers who support freedom of speech to republish Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons. (Some publishers have refused, for myriad reasons.)

Some specific examples of #JeSuisCharlie in action include Twitter users changing their avatars to images of the prophet Mohammed from the pages of Charlie Hebdo (a move calculated to provoke Muslims, as some adherents argue that Islam forbids pictorial representations of the prophet); the dissemination of cartoonists’ responses to the attack (even mistakenly attributing one response to Banksy, and claiming some that appeared years prior to the attack); and the production of endless think pieces that rehash the clash-of-civilisations, Islam-vs.-the-West’s-freedoms rhetoric with which we have all become depressingly familiar in the years following 9/11.

The core manouevre of #JeSuisCharlie is that of universalisation: today, this spontaneous movement says, we are all Charlie Hebdo. As a corollary, this one, specific event is not to be understood in its specificity, but as a synecdoche for broader issues: the confrontation between the liberal West and Islamic fundamentalism, the tension between freedom of the press and freedom of religion, or the necessity of restating classically liberal values in the face of terrorism.

The #JeSuisCharlie movement is correct to an extent: the very fact that this attack has garnered so much media attention outside France indicates that it taps into a tangle of hot-button issues that currently cause concern across the Western world. But in its move towards universalisation, the #JeSuisCharlie movement elides much of the specificity of Charlie Hebdo’s satire and its relationship to French politics and French multiculturalism – all of which are without parallel in the political and cultural Anglosphere of the UK, the US, and Australia.

The differences between France and the English-speaking West are much deeper than the language (or the stereotypical skinny loaves of bread and pungent cheeses), and in the light of those differences we should pause before affirming that nous sommes tous Charlie Hebdo.

The untranslatability of Charlie Hebdo’s humour: Is it racist, or what?

This may sound so obvious as to be almost redundant, but it bears repeating: Charlie Hebdo is a French satirical magazine, therefore its satire doesn’t make much sense outside of the French context.

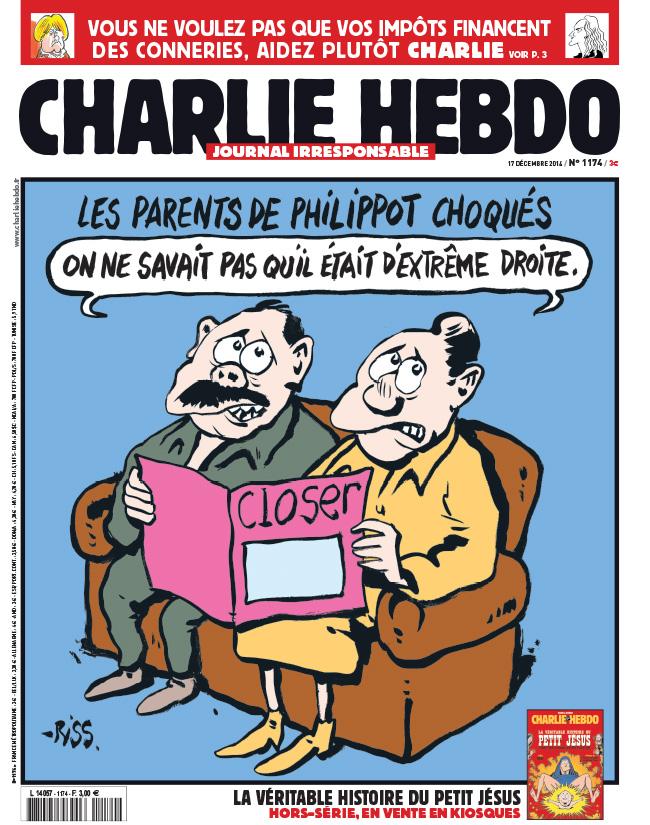

Take, for example, the cover of Charlie Hebdo’s issue of December 17 of last year (above), which depicts the parents of Front National politician Florian Philippot reading the French tabloid Closer. The headline translates as “Philippot’s parents shocked”, and the speech bubble as “We didn’t know he was extreme right”. The gag only makes sense if you know that Philippot was recently involved in a scandal on the pages of Closer when he was photographed with a secret gay partner (who has since confirmed that he and Philippot are dating).

But more than requiring a knowledge of the latest French political scandals, the Charlie Hebdo cover requires you to share their worldview: one where homosexuality is normalised, and membership in a far-right party such as Front National is scandalous. In fact, Charlie Hebdo’s editorial position is (or was) consistently left-wing – left-wing, that is, within the world of French politics.

This statement might be hard to square with what some have characterised as the overt racism of Charlie Hebdo’s imagery. For example, Charlie Hebdo published a caricature of the French Minister of Justice, Christiane Taubira – who happens to be black – as a monkey.

Charlie Hebdo cartoon portraying black Minister of Justice Christiane Taubira as a monkey #JeNeSuisPasCharlie pic.twitter.com/MMmBj4TQOc

— Max Blumenthal (@MaxBlumenthal) January 8, 2015

[This image no longer exists on Max Blumenthal’s Twitter page]

The kind of imagery above would be completely beyond the pale of political discourse in the Anglophone world, and for good reason. So why was it used by Charlie Hebdo? The accompanying caption offers a clue: Rassemblement bleue raciste, a pun on the name of Rassemblement bleu Marine, a political coalition set up by far-right politician Marine Le Pen – who recently called the left-wing Taubira a “monkey”. The caricature therefore does something that few Anglophone cartoonists would dare attempt: it uses overtly racist imagery as a means of satirising racism.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2925558/CHARLIE-HEBDO.0.jpg)

This Charlie Hebdo October 2014 cover reads “Boko Haram’s sex slaves are angry.” The women are shouting, “Don’t touch our welfare!”

Even the most patently offensive of the Charlie Hebdo covers that have been circulating on the internet in the wake of the attack – one [above] depicting the Nigerian girls and women kidnapped by Boko Haram as pregnant welfare queens – has been read by observers in France as a satire of the paranoid fantasies of the far-right. (That the same cover was met with criticism for its Islamophobia within France demonstrates that French left-wing politics are not monolithic, just as left-wing politics around the world are not monolithic.)

The fact that Charlie Hebdo’s editorial position is left-wing within the world of French politics necessarily complicates any analysis of their imagery as purely and simply racist. Of course, left-wing people and self-described progressives are not immune from racism; Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail talks eloquently about the soft racism of the ‘white moderate’ being as much of an impediment to black freedom as the Ku Klux Klan. And I would personally argue that racist imagery is so loaded with an unsavoury history of racist use that it is nearly impossible to ‘reclaim’ in the service of anti-racist action – certainly not if deployed with the crudeness of Charlie Hebdo’s more offensive pieces. This is before we even consider the very important question of whether representing the prophet Mohammed in any form is needlessly antagonistic towards Sunni Muslims, whose interpretations of the hadith prohibit the pictorial representation of the prophet – or, as French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius put it, “Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?”.

Progressive voices in the Anglosphere have interpreted the magazine as a bastion of racism, classism, and homophobia, without seeking to understand its context.

Yet in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, left-wing and progressive voices in the Anglosphere have interpreted the magazine as a bastion of racism, classism, and homophobia, without seeking to understand the magazine’s context. (Similarly, voices of the American right such as Larry O’Connor – who the profoundly left and secular Charlie Hebdo staff would have abhorred – have seen fit to declare solidarity with the magazine.) As Jeff Sparrow argues, “you don’t have to like the project of Charlie Hebdo to defend its artists from murder, just as you can uphold media workers’ right to safety without endorsing the imagery they produce.”

This seems especially salient when, owing to our immersion within the Anglophone political landscape, most of us are not even in a position to accurately decode Charlie Hebdo’s message, or understand its humour.

Islamophobia in France: a different beast

Unless you are an avid Francophile with a particular interest in its domestic politics, you might be forgiven for thinking that France is some kind of hotbed of Islamophobic sentiment. When stories about the relationship between French Muslims and the rest of the country’s citizens make the international news – such as the trial of Michel Houellebecq, riots in the banlieues of Paris, or the controversial burqa ban – the average French citizen is presented as someone who absolutely detests Islam and its adherents.

The truth is, as always, a little bit more complicated.

France, like any other pluralist country, contains a multitude of political platforms and positions, from the ultra-right reactionary Front National to a full-blown Socialist party powerful enough to currently hold the presidency. Among its citizens you will therefore find a diverse range of opinions about Islam, some as rabid as our own Pauline Hanson and some as tolerant as the most ardent Australian left-winger.

The last time I visited Paris was during last year’s Ramadan, the Islamic month of daylight fasting and evening feasting. And if I didn’t know it was Ramadan before I arrived, I couldn’t avoid discovering it while I was there: an advertising campaign by an importer of Middle Eastern foods (couscous, dates, etc.) wishing all and sundry a ‘bon Ramadan’ was plastered over seemingly every stop of Paris’s Métro. (Just imagine the collective pants-shitting from the Halal-funds-terrorism crowd that would accompany such a campaign here in Australia.)

Muslims make up a huge minority group in France, one much larger both proportionally and numerically than Australia’s Muslim community, at around five to six million adherents out of a population of 66 million, or just under 10% of the population (although French census law makes it impossible for anyone to know accurately). We do know for sure that France has the largest Muslim community in Western Europe. This alone changes the dynamic between the average non-Muslim French person and their Muslim French counterpart: where the average white Australian can live their lives without any significant contact with Australia’s relatively small Muslim community (2.2% of the population, according to the 2011 census), the average non-Muslim French person is more likely to live next door to or work with a Muslim.

This doesn’t mean France is some kind of harmonious wonderland: the recent electoral successes of the Front National ought to demonstrate that familiarity sometimes breeds contempt. But it does mean that a Muslim presence in France is accepted as a fact of life for most French people – in marked contrast to the ‘fuck off, we’re full’ crowd here in Australia, who seem to believe that an Islam-free Australia is both possible and desirable.

Liberté, egalité, fraternité: why French politics aren’t like ours

While Islamophobia in Australia is strongly associated with the political right – see: Hanson, Bernardi, Pell & co. – and tolerance of Islam with the political left, in France the issue is not so clear-cut. The French concept of laïcité – the absolute separation of church and state – is enshrined in French law and the constitution, to the extent that “bringing religion into public affairs [is] a major taboo.” (This strong prohibition is the reason why it is illegal for the French census to even measure the demographics of French religion.) Thus, even though by some accounts Catholics make up a majority of French citizens, the ground for political debate in the country is thoroughly secular. This means that debates that have gained traction around the world recently – to do with immigration, same-sex marriage, and other hot-button topics – often play out very differently in France than they do elsewhere. For instance, as Camille Robcis notes in a recent interview with Jacobin, even though the opposition to same-sex marriage in France is being led from the Catholic right, the arguments they deploy against same-sex marriage come from the radical left.

Similarly, the debate over the burqa in France had less to do with complete intolerance for Islam, and more to do with the question of integration: or, as Robcis puts it in her interview, whether the burqa “represented a fundamental attachment to a particular interest (Islam), a form of communitarianism fundamentally incompatible with France”. In this context it’s not impossible for a left-wing magazine such as Charlie Hebdo to be Islamophobic, nor for reactionary authors such as Houellebecq – who, let us not forget, was once sued for his previous statements about Islam – to imagine an alliance between Catholics and Muslims against the secular enlightenment philosophy that currently structures French political life.

None of this excuses Islamophobia in France – and it’s worth remembering that in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack vigilantes across France have attacked a mosque, an Islamic prayer hall, and a kebab shop – but it does mean that French Islamophobia is not the same thing at all as the Islamophobia with which we are familiar here in Australia. (For example: while publications around the world were keen to peg the 2005 banlieue riots to terrorism and jihad, in France the discussion was dominated by socio-economic issues.) The issue in France is not Islam itself, but its role in public life and whether certain cultural and religious practices are compatible with the universal principles of French republicanism.

How should we respond to the Charlie Hebdo attacks?

One of the amazing things about the response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks is how swift people have been – both in social media and elsewhere – to declare allegiances and draw battle lines. On the one hand we are being exhorted to show our support for freedom of speech by redistributing Charlie Hebdo’s content, even when we don’t have the contextual knowledge to properly understand that content. On the other, critics of Charlie Hebdo’s work have ignored the very specific French political context, and assumed that the magazine must have been a hotbed of right-libertarian racism, sexism, and homophobia.

How do we begin to understand something as complex as what appears to be an Islamic terrorist attack on a left-wing satirical journal, in a country whose politics fundamentally don’t resemble ours? We could start by resisting the temptation to make declarations of allegiance – to avoid the easy solution of shouting #JeSuisCharlie unless we’re absolutely certain that we are, in fact, of the same mindset as Charlie Hebdo. We could restate, as often as possible, the necessary message that there’s nothing contradictory about supporting freedom of the press, finding political violence abhorrent, and also finding Charlie Hebdo’s use of racist imagery (for whatever political end) repellent.

We could, most importantly, respect the dead by trying to understand where they were coming from, and resisting the urge to make Charlie Hebdo stand for something it never has.

Chad Parkhill is a Melbourne-based writer and editor, who has written for The Australian, The Lifted Brow, Meanjin and The Quietus amongst others.

By Adam Shatz, blog, LRB

January 09, 2015

After 9/11, Le Monde declared: ‘Nous sommes tous Américains.’ The love affair was short-lived: as soon as the French declined to join the war against Iraq, American pundits called them ‘cheese-eating surrender monkeys’ and French fries were renamed ‘freedom fries’. When Obama took office, relations warmed, but the tables were turned: the new administration in Washington shied from foreign adventures, while the Elysée adopted a muscular stance in Libya and Mali, and promoted a more aggressive response to Bashar al-Assad’s assault on the Syrian rebellion. Neoconservatives who had vilified the surrender monkeys now looked at them with envy.

Today a new cry can be heard among intellectuals in the US: ‘Je suis Charlie.’ It is a curious slogan, all the more so since few of the Americans reciting it had ever heard of, much less read, Charlie Hebdo before the 7 January massacre. What does it mean, exactly? Seen in the best light, it means simply that we abhor violence against people exercising their democratic right to express their views. But it may also be creating what the French would call an amalgame, or confusion, between Charlie Hebdo and the open society of the West. In this sense, the slogan ‘je suis Charlie’ is less an expression of outrage and sympathy than a declaration of allegiance, with the implication that those who aren’t Charlie Hebdo are on the other side, with the killers, with the Islamic enemy that threatens life in the modern, democratic West, both from outside and from within.

Already, anyone who dares to examine the causes of the massacre, the reasons the Kouachi brothers drifted into jihadist violence, is being warned that to do so is to excuse the real culprit, radical Islam: ‘an ideology that has sought to achieve power through terror for decades’, as George Packer wrote on the New Yorker blog. Packer says this is no time to talk about the problem of integration in France, or about the wars the West has waged in the Middle East for the last two decades. Radical Islam, and only radical Islam, is to blame for the atrocities. We are in what the New Yorker critic George Trow called the ‘context of no context’, where jihadi atrocities can be safely laid at the door of an evil ideology, and any talk of pre-emptive war, torture and racism amounts to apologia for atrocities.

We have been here before: the 11 September attacks led many liberal intellectuals to become laptop bombardiers, and to smear those, such as Susan Sontag, who reminded readers that American policies in the Middle East had not won us many friends. The slogan ‘je suis Charlie’ expresses a peculiar nostalgia for 11 September, for the moment before the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, before Abu Ghraib and extraordinary rendition, before all the things that did so much to tarnish America’s image and to muddy the battle lines. In saying ‘je suis Charlie’, we can feel innocent again. Thanks to the massacre in Paris, we can forget the Senate torture report, and rally in defence of the West in good conscience.

Packer’s article isn’t surprising, but it’s also symptomatic. He reacted to 9/11 by supporting the invasion of Iraq. He later became a critic of the war, or at least of its execution. Yet he responded to the Paris massacre by resorting to the same rhetoric about Islamic ‘totalitarianism’ that he invoked after 9/11. He even hints at a civilisational war between Us and Them – or, at least, some of Them, the ‘substantial minority of believers who countenance… a degree of violence in the application of their convictions that is currently unique’. That such rhetoric helped countenance the disasters of Afghanistan and Iraq seems not to occur to him, bathed as he is in what liberal hawks like to call ‘moral clarity’. To demonstrate ‘moral clarity’ is to be on the right side, and to show the courage of a fighting faith, rather than the timorous, context-seeking analysis of those soft on what Christopher Hitchens called ‘Islamofascism’. Packer’s New Yorker article is a declaration of this faith, a faith he confuses with liberalism.

In laying exclusive blame for the Paris massacres on the ‘totalitarian’ ideology of radical Islam, liberal intellectuals like Packer explicitly disavow one of liberalism’s great strengths. Modern liberalism has always insisted that ideology can go only so far in explaining behaviour. Social causes matter. The Kouachi brothers were products of the West – and of the traumatic collision between Western power and an Islamic world that has been torn apart by both internal conflict and Western military intervention. They were, above all, beurs, French citizens from the banlieue: Parisians of North African descent. It’s unlikely they could have recited more than the few hadith they learned from the ex-janitor-turned-imam who presided over their indoctrination. They came from a broken family and started out as petty criminals, much like Mohamed Merah, who murdered a group of Jewish schoolchildren in Montauban and Toulouse in 2012. Their main preoccupations, before their conversion to Islamism, seem to have been football, chasing girls, listening to hip hop and smoking weed. Radical Islam gave them the sense of purpose that they couldn’t otherwise find in France. It allowed them to translate their sense of powerlessness into total power, their aimlessness into heroism on the stage of history. They were no longer criminals but holy warriors. To see their crimes as an expression of Islam is like treating the crimes of the Baader-Meinhof gang as an expression of historical materialism. And to say this is in no way to diminish their responsibility, or to relinquish ‘moral clarity’.

Last night I spoke with a friend who grew up in the banlieue. Assia (not her real name) is a French woman of Algerian origin who has taught for many years in the States, a leftist and atheist who despises Islamism. She read Charlie Hebdo as a teenager, and revelled in its irreverent cartoons. She feels distraught not just by the attacks but by the target, which is part of her lieux de mémoire. A part of her will always be Charlie Hebdo. And yet she finds it preposterous – and disturbing – that even Americans are now saying ‘je suis Charlie.’ Have any of them ever read it? she asked. ‘You couldn’t publish Charlie in the US – not the cartoons about the Prophet, or the images of popes getting fucked in the ass.’ Charlie Hebdo had an equal opportunity policy when it came to giving offence, but in recent years it had come to lean heavily on jokes about Muslims, who are among the most vulnerable citizens in France. Assia does not believe in censorship, but wonders: ‘Is this really the time for cartoons lampooning the Prophet, given the situation of North Africans in France?’

That’s ‘North Africans’, not ‘Muslims’. ‘When I hear that there are five million Muslims in France,’ Assia says, ‘I don’t know what they’re talking about. I know plenty of people in France who are like me, people of North African origin who don’t pray or believe in God, who aren’t Muslims in any real way. We didn’t grow up going to mosque; at most we saw our father fasting at Ramadan. But we’re called Muslims – which is the language of Algérie Française, when we were known as indigènes or as Muslims.’ She admits that more and more young beurs are becoming religious, but this is as much an expression of self-defence as piety, she says: French citizens of North African origin feel their backs are against the wall. That they are turning to an imported form of Islam – often of Gulf origin, often radical – is no surprise: few of them have any familiarity with the more peaceful and tolerant Islam of their North African ancestors. Nor is it surprising to find an increasing anti-Semitism among French Maghrébins in the banlieue. They look at the Jews and see not a minority who were persecuted by Europe but a privileged elite whose history of victimisation is officially honoured and taught in schools, while the crimes of colonisation in Algeria are still hardly acknowledged by the state.

Assia is typically Parisian, in her dress, accent and lifestyle. But that did not prevent her from being reminded, at every turn, of her otherness. ‘Assia, what sort of name is that?’ people would ask her since she was a child. With its strong centralising traditions, France shuns expressions of difference, notably the hijab, but continues to treat French citizens of Muslim origin as foreigners. Second and third-generation citizens are still routinely described as ‘immigrants’. The message: don’t wear the hijab, you’re French; but don’t bother applying for this job if your name is Mohammed. ‘When my brothers were growing up,’ Assia told me, ‘they would be stopped by the police ten to fifteen times a day – on the bus, getting off the bus, on their way to school, on their way home. Girls weren’t stopped; only boys. The French are more comfortable with “Fatima” than with “Mohammed”.’ French women of North African origin are doing better than men – which in part explains why some of the unemployed men take to dominating their mothers and sisters, as if they were their property, their only property. Assia is one of many French Maghrébins who have found it much easier to live outside France.

To say that France has an integration problem, and that it’s in urgent need of repair, isn’t to let the killers – or, pace Packer, their ideology – off the hook. It is to take the full measure of the moral and political challenge at hand, rather than to indulge in self-congratulatory exercises in ‘moral clarity’. If France continues to treat French men of North African origin as if they were a threat to ‘our’ civilisation, more of them are likely to declare themselves a threat, and follow the example of the Kouachi brothers. This would be a gift both to Marine Le Pen and the jihadists, who operate from the same premise: that there is an apocalyptic war between Europe and Islam. We are far from that war, but the events of 7 January have brought us a little closer.

Is there something about Islam?

By Kenan Malik, Pandaemonium

August 12, 2014

I took part on Saturday in a panel discussion at the World Humanist Congress in Oxford on ‘Is there something about Islam?’ which debated whether ‘there is anything distinctive about Islam’ that leads to violence, bigotry and the suppression of freedom. Other panellists were Alom Shaha, Maajid Nawaz and Maryam Namazie. This is a transcript of my introductory comments.

Every year I give a lecture to a group of theology students – would-be Anglican priests, as it happens – on ‘Why I am an atheist’. Part of the talk is about values. And every year I get the same response: that without God, one can simply pick and choose about which values one accepts and which one doesn’t.

My response is to say: ‘Yes, that’s true. But it is true also of believers.’ I point out to my students that in the Bible, Leviticus sanctifies slavery. It tells us that adulterers ‘shall be put to death’. According to Exodus, ‘thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’. And so on. Few modern day Christians would accept norms. Others they would. In other words, they pick and choose.

So do Muslims. Jihadi literalists, so-called ‘bridge builders’ like Tariq Ramadan (‘bridge-builder’, I know, is a meaningless phrase, and there are many other phrases that one could, and should, use to describe Ramadan) and liberals like Irshad Manji all read the same Qur’an. And each reads it differently, finding in it different views about women’s rights, homosexuality, apostasy, free speech and so on. Each picks and chooses the values that they consider to be Islamic.

I’m making this point because it’s one not just for believers to think about, but for humanists and atheists too. There is a tendency for humanists and atheists to read religions, and Islam in particular, as literally as fundamentalists do; to ignore the fact that what believers do is interpret the same text a hundred different ways. Different religions clearly have different theologies, different beliefs, different values. Islam is different from Christianity is different from Buddhism. What is important, however, is not simply what a particular Holy Book, or sacred texts, say, but how people interpret those texts.

.jpg)

Famously peaceful Buddhist monks in Myanmar/ Burma before their Muslim-killing rampage.

The relationship between religion, interpretation, identity and politics can be complex. We can see this if we look at Myanmar and Sri Lanka where Buddhists – whom many people, not least humanists and atheists, take to be symbols of peace and harmony – are organizing vicious pogroms against Muslims, pogroms led by monks who justify the violence using religious texts. Few would insist that there is something inherent in Buddhism that has led to the violence. Rather, most people would recognize that the anti-Muslim violence has its roots in the political struggles that have engulfed the two nations. The importance of Buddhism in the conflicts in Myanmar and Sri Lanka is not that the tenets of faith are responsible for the pogroms, but that those bent on confrontation have adopted the garb of religion as a means of gaining a constituency and justifying their actions. The ‘Buddhist fundamentalism’ of groups such as the 969 movement, or of monks such as Wirathu, who calls himself the ‘Burmese bin Laden’, says less about Buddhism than about the fractured and fraught politics of Myanmar and Sri Lanka.

And yet, few apply the same reasoning to conflicts involving Islam. When it comes to Islam, and to the barbaric actions of groups such as Isis or the Taliban, there is a widespread perception that the problem, unlike with Buddhism, lies in the faith itself. Religion does, of course, play a role in many confrontations involving Islam. The tenets of Islam are very different from those of Buddhism. Nevertheless, many conflicts involving Islam have, like the confrontations in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, complex social and political roots, as groups vying for political power have exploited religion and religious identities to exercise power, impose control and win support. The role of religion in these conflicts is often less in creating the tensions than in helping establish the chauvinist identities through which certain groups are demonized and one’s own actions justified. Or, to put it another way, the significance of religion lies less in a given set of values or beliefs than in the insistence that such values or beliefs – whatever they are – are mandated by God.

And it is in this context we need to think about whether there is ‘something about Islam’. There is a host of different views that Muslims hold on issues from apostasy to free speech, views that range from the liberal to the reactionary. The trouble is that policymakers and commentators, particularly in the West, often take the most reactionary views to be the most authentic stance, in a way they would rarely do with Buddhism or Judaism or Christianity.

The Danish MP Naser Khader once told me once of a conversation with Toger Seidenfaden, editor of Politiken, a left-wing Danish newspaper that was highly critical of the Danish cartoons. ‘He said to me that cartoons insulted all Muslims’, Khader recalled. ‘I said I was not insulted. And he said, “But you’re not a real Muslim”.’

‘You’re not a real Muslim.’ Why? Because to be proper Muslim is, from such a perspective, to be reactionary, to find the Danish cartoons offensive. Anyone who isn’t reactionary or offended is by definition not a proper Muslim. Here leftwing ‘anti-racism’ meets rightwing anti-Muslim bigotry. For many leftwing anti-racists, opposing bigotry means accepting reactionary ideas as authentically Muslim. For many rightwing bigots (and, indeed, for many leftwing bigots, too), there is something about Islam that makes it irredeemably violent, even evil, and that all Muslims potentially dangerous.

Here also, liberal so-called anti-racism becomes a vehicle for buttressing the most reactionary, conservative voices in Muslim communities and for marginalizing the progressive. It becomes a means of closing down debate, censoring criticism, and giving power and legitimacy to ‘community leaders’ spouting the most backward of views. ‘The controversy over the cartoons’, as Naser Khader observed, ‘was not about Muhammad. It was about who should represent Muslims. What I find really offensive is that journalists and politicians see the fundamentalists as the real Muslims.’ Which is why many Muslims. ironically, often have more liberal views on free speech than many so-called liberal non-believers.

The real problem, then, is not simply Islam as such. Nor is it even simply the conservative strands of Islam, though such strands clearly embody odious views, are often viciously intolerant, and, where they give rise to movements such as the Taliban or Isis, can be demonically inhuman. The problem is also the attitudes of non-Muslim commentators, policymakers and activists, both liberals and bigots, as to what constitutes an authentic Muslim, the failure to see beyond the conservative or the reactionary as the true Muslim, the inability to distinguish between the faith of ordinary believers and the politicised use of faith for reactionary ends by power-grabbing, control-seeking individuals and organisations. The problem is also government policy, particularly in the West. Policy makers have all too often treated minority communities as if each was a distinct, homogeneous whole, each composed of people all speaking with a single voice, each defined primarily by a singular view of culture and faith. They have ignored the diversity within those communities and taken the most conservative, reactionary figures to be the authentic voices.

And worse, the problem lies also in the attempts by governments to encourage reactionary religious forces to act as counterweights to radical opposition, often with disastrous consequences. There is, for instance, a terrible irony in Israel’s current assault on Gaza. It was Israel itself that helped Hamas to power in the first place, viewing radical Islamism as a useful tool with which to counter the influence of the secular PLO. Cynical it may have been, but there was nothing exceptional about such policy. Many governments, Western and non-Western, have pursued similar strategies, strategies that have consistently strengthened the hand of the reactionaries against the progressives: from Egypt in the 1970s looking to the Muslim Brotherhood to keep the radical left opposition in check; to America helping fund and arm jihadis in Afghanistan; to even the French government, which supposedly disdains ‘Anglo-Saxon communalism’, encouraging communal Islamic identity when it has proved politically expedient. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s government, for instance, faced with a series of major strikes involving mainly North African workers, encouraging the building of prayer rooms in factories, because in the words of immigration minister Paul Dijoud, ‘Islam is a stabilizing force which would turn the faithful from deviance, delinquency or membership of unions or revolutionary parties.’

So, yes there is something about Islam that needs challenging. But equally, there is something about secular liberalism, and the blindness and pusillanimity of many secular liberals, the bigotry of many critics of Islam, and the cynicism of many secular governments in their exploitation of radical Islam, that needs challenging too.

What everyone gets wrong about Charlie Hebdo and racism

By Max Fisher, Vox

January 12, 2015

Over the past week, millions of people who had never heard of French magazine Charlie Hebdo have come into contact with its controversial covers and cartoons. And many have come away with questions about those cartoons, including a nagging sense that their depictions of Islam and people of color have been insensitive, or even racist.

Some argue that any questioning of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons implies sympathy with the terrorists or is tantamount to criticism of free speech itself, but this is a fallacy. We, as a society, have all agreed that there can never be any justification for such an attack and that free speech is an irreducible value. That question has been answered.

But an entirely separate set of questions still stand: are Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons racist? Did they go a step beyond satire and become something uglier?

What Charlie Hebdo’s critics get wrong about its satire

To broach this question, it helps to start with a cover that is not specifically about Islam — we’ll get to that later — and that has been widely circulated among Charlie Hebdo’s non-French critics as one of the magazine’s most obviously racist.

Here’s what the cover shows: a group of headscarf-wearing, pregnant Nigerian women shouting “Don’t touch our welfare!” The title reads, “Boko Haram’s sex slaves are angry.”

On the surface, then, it would appear that the magazine is ridiculing Nigerian human trafficking victims as welfare queens; hence the outrage among non-French readers. However, that is not actually what the cover is conveying. In many ways it’s saying the opposite of critics’ interpretations.

French satire, as Vox’s Libby Nelson explained, is not so straightforward as it would seem; jokes usually play on two layers. In this cover, the second layer has to do with French domestic politics: Charlie Hebdo is a leftist magazine that supports welfare programs, but the French political right tends to oppose welfare for immigrants, whom they characterize as greedy welfare queens cheating the system.

What this cover actually says, then, is that the French political right is so monstrous when it comes to welfare for immigrants, that they want you believe that even Nigerian migrants escaping Boko Haram sexual slavery are just here to steal welfare. Charlie Hebdo is actually lampooning the idea that Boko Haram sex slaves are welfare queens, not endorsing it.

That’s what’s tricky about two-layer satire like Charlie Hebdo’s: the joke only works if you see both layers, which often requires conversant knowledge of French politics or culture. If you don’t see that layer, then the covers can seem to say something very different and very racist.

The New Yorker did almost the exact same thing in 2008

To get a sense of how Charlie Hebdo’s two-layer humor works, recall this [image at top] 2008 cover from the New Yorker. It portrayed Barack Obama, then a presidential candidate, as Muslim. And it portrayed his wife, Michelle Obama, as a rifle-toting militant in the style of the black nationalists of the 1960s. It caused some controversy.

If you saw this cover knowing nothing about the New Yorker or very little about American politics, you would read it as a racist and Islamophobic portrayal of the Obamas, an endorsement of the idea that they are secret black nationalist Muslims. In fact, though, most Americans immediately recognized that the New Yorker was in fact satirizing Republican portrayals of the Obamas, and that the cover was lampooning rather than endorsing that portrayal.

To understand Charlie Hebdo covers, you have to look at them the same way that you look at this New Yorker cover. And you also have to know something about the context of French politics and social issues. Many non-French readers coming to Charlie Hebdo don’t have that context and don’t know to look for that second layer, and so are reading the covers as something they are not.

But.

Charlie Hebdo’s satire makes high-minded points, but indulges racism along the way

Again, scroll up to the Boko Haram cover, looking at it again through the lens of the New Yorker cover and reading it as a comment on the French right’s anti-welfare politics. It looks a lot less racist. But it still looks racist. (Similarly, a number of Americans who understood the New Yorker nevertheless still felt it went too far.)

You don’t need me to walk you through the way that these women are drawn to see the racist tropes in their depiction — tropes that come directly from colonial-era racist ideas about Africans as sub-human, and tropes that are unnecessary to make the magazine’s point about welfare. And the emphasis of the cover, making light of Nigerian victims of mass rape in order to skewer French politicians, is uncomfortably revealing. The very real suffering of these women is treated insensitively, as a low priority.

This is a regular pattern in Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons, even if you see the two-layer satire they often play at. People of color are routinely portrayed with stereotypical features — Arabs given big noses, Africans given big lips — that are widely and correctly considered racist. These features are not necessary for the jokes to work, or for the characters to be recognizable. And yet Charlie Hebdo has routinely included them, driving home a not-unreasonable sense that the magazine’s cartoons indulged racism.

Further, the portrayal of people of color, as well as Muslims of all races, has been consistently and overwhelming negative in Charlie Hebdo cartoons. Reading Charlie Hebdo cartoons and covers in the aggregate, a reader is given the uniform and barely-concealed message that Muslims are categorically bad, violent, irrational people. This characterization indulges and indeed furthers some of the widest and most basic stereotypes of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims. That would certainly seem to be racism in its most unmistakable and transparent form.

(There is a counter-argument among Islamophobes that Islam is not a race and thus racism against Muslims is impossible. I have heard enough sweeping statements conflating Islam with Arabs to know that Islamophobia is often experienced and indeed expressed as about race, but if you prefer, you may read “racism” as bigotry here.)

Charlie Hebdo’s biggest problem isn’t racism, it’s punching down

There are counter-arguments to the assertion that Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons are racist. One is that its depictions are meant to satirize racist portrayals rather than endorse them, as with the Boko Haram cover.

Another counter-argument is that its lampooning of radical Islam is aimed at separating out radicalism from mainstream Islam, which is ultimately a service in favor of Islam. The magazine’s own editors have said this. “We want to laugh at the extremists — every extremist,” Laurent Léger, who survived the attack, told CNN in 2012. “They can be Muslim, Jewish, Catholic. Everyone can be religious, but extremist thoughts and acts we cannot accept.”

One cover, for example, portrays a member of ISIS poised to decapitate the Prophet Mohammed; Mohammed says, “I’m the Prophet, asshole!”

But just as we have to consider the larger context when understanding the intent of Charlie Hebdo’s satire, so too must we consider that larger context when evaluating the satire’s effect. And that larger context is not flattering to Charlie Hebdo.

French society is in the middle of what we in the United States would call a culture war. Though French colonialism ended in the 1950s and 1960s, France has absorbed a large number of immigrants, many of them Muslim, from former colonies in North and West Africa. Those immigrants and their descendants face systemic discrimination.

France’s white majority, whether Catholic or secular, tends to be highly skeptical of the idea that the immigrants can ever truly assimilate or be French. This is often expressed as hostility to Muslims or to Islam itself. These attitudes make it very difficult to be a Muslim, or ethnically non-white, in France.

Within the French culture war, Charlie Hebdo stands solidly with the privileged majority and against the under-privileged minorities. Yes, sometimes it also criticizes Catholicism, but it is best known for its broadsides against France’s most vulnerable populations. Put aside the question of racist intent: the effect of this is to exacerbate a culture of hostility, one in which religion and race are also associated with status and privilege, or lack thereof.

The novelist Saladin Ahmed articulated well why this sort of satire does not exactly have the values-championing effect we want it to:

In a field dominated by privileged voices, it’s not enough to say “Mock everyone!” In an unequal world, satire that mocks everyone equally ends up serving the powerful. And in the context of brutal inequality, it is worth at least asking what preexisting injuries we are adding our insults to.

The belief that satire is a courageous art beholden to no one is intoxicating. But satire might be better served by an honest reckoning of whose voices we hear and don’t hear, of who we mock and who we don’t, and why.

Jacob Canfield put it more simply: “White men punching down is not a recipe for good satire, and needs to be called out.”

This is a culture war with real victims. Fighting on the winning side and against a systemically disadvantaged group, fighting on behalf of the powerful against the weak, does not seem to capture the values that satire is meant to express.

Charlie Hebdo is Western society at its best and worst

So if Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons expressed or indulged racist ideas, and if its satire “punched down” in ways that were more regrettable than admirable, then why does it feel so uncomfortable to criticize the magazine?

It’s partly because, whatever the magazine’s misdeeds, they are so utterly incomparable to the horrific crimes of the terrorists who attacked it that it can feel like a betrayal to even mention them in the same sentence.

But it’s also because, with this attack, Charlie Hebdo really has come to symbolize something much larger than the satire embedded with its cartoons: a resolve to maintain freedom of speech even in the face of mortal threats. While free speech is not at the risk of being snuffed out in Western countries over these sorts of attacks, it is an abstract value that is constantly under siege in the world and requires constant defense. The cartoons have become a symbol of that fight.

“Unforgivable acts of slaughter imbue merely rude acts of publication with a glittering nobility,” Matthew Yglesias wrote last week. “To blaspheme the Prophet transforms the publication of these cartoons from a pointless act to a courageous and even necessary one.”

And yet, raising these cartoons to something much grander does have victims. As is so often the case, those victims are society’s weakest and most vulnerable, in this case the Muslim and non-white subjects of Charlie Hebdo’s belittling ridicule.

“The elevation of such images to a point of high principle will increase the burdens on those minority groups,” as Matt put it. “European Muslims find themselves crushed between the actions of a tiny group of killers and the necessary response of the majority society. Problems will increase for an already put-upon group of people.”

The virtues that Charlie Hebdo represents in society — free speech, the right to offend — have been strengthened by this episode. But so have the social ills that Charlie Hebdo indulged and worsened: empowering the majority, marginalizing the weak, and ridiculing those who are different.

On Charlie Hebdo: A letter to my British friends

By Olivier Tonneau, blog, Mediapart

January 11, 2015

Dear friends,

Three days ago, a horrid assault was perpetrated against the French weekly Charlie Hebdo, who had published caricatures of Mohamed, by men who screamed that they had “avenged the prophet”. A wave of compassion followed but apparently died shortly afterward and all sorts of criticism started pouring down the web against Charlie Hebdo, who was described as islamophobic, racist and even sexist. Countless other comments stated that Muslims were being ostracized and finger-pointed. In the background lurked a view of France founded upon the “myth” of laïcité, defined as the strict restriction of religion to the private sphere, but rampantly islamophobic – with passing reference to the law banning the integral veil. One friend even mentioned a division of the French left on a presumed “Muslim question”.

As a Frenchman and a radical left militant at home and here in UK, I was puzzled and even shocked by these comments and would like, therefore, to give you a clear exposition of what my left-wing French position is on these matters.

Firstly, a few words on Charlie Hebdo, which was often “analyzed” in the British press on the sole basis, apparently, of a few selected cartoons. It might be worth knowing that the main target of Charlie Hebdo was the Front National and the Le Pen family. Next came crooks of all sorts, including bosses and politicians (incidentally, one of the victims of the shooting was an economist who ran a weekly column on the disasters caused by austerity policies in Greece). Finally, Charlie Hebdo was an opponent of all forms of organized religions, in the old-school anarchist sense: Ni Dieu, ni maître! They ridiculed the pope, orthodox Jews and Muslims in equal measure and with the same biting tone. They took ferocious stances against the bombings of Gaza. Even if their sense of humour was apparently unacceptable to English minds, please take my word for it: it fell well within the French tradition of satire – and after all was only intended for a French audience. It is only by reading or seeing it out of context that some cartoons appear as racist or islamophobic. Charlie Hebdo also continuously denounced the pledge of minorities and campaigned relentlessly for all illegal immigrants to be given permanent right of stay. I hope this helps you understand that if you belong to the radical left, you have lost precious friends and allies.

This being clear, the attack becomes all the more tragic and absurd: two young French Muslims of Arab descent have not assaulted the numerous extreme-right wing newspapers that exist in France (Minute, Valeurs Actuelles) who ceaselessly amalgamate Arabs, Muslims and fundamentalists, but the very newspaper that did the most to fight racism. And to me, the one question that this specific event raises is: how could these youth ever come to this level of confusion and madness? What feeds into fundamentalist fury? How can we fight it?

I think it would be scandalous to answer that Charlie Hebdo was in any way the cause of its own demise. It is true that some Muslims took offence at some of Charlie’s cartoons. Imams wrote in criticism of them. But the same Imams were on TV after the tragedy, expressing their horror and reminding everyone that words should be fought with words, and urging Muslims to attend Sunday’s rally in homage to Charlie Hebdo. As a militant in a party that is routinely vilified in the press, I don’t go shoot down the journalists whose words or pictures trigger my anger. It is a necessary consequence of freedom of expression that people might be offended by what you express: so what? Nobody dies of an offence.

Of course, freedom of speech has its limits. I was astonished to read from one of you that UK, as opposed to France, had laws forbidding incitement to racial hatred. Was it Charlie’s cartoons that convinced him that France had no such laws? Be reassured: it does. Only we do not conflate religion and race. We are the country of Voltaire and Diderot: religion is fair game. Atheists can point out its ridicules, and believers have to learn to take a joke and a pun. They are welcome to drown us in return with sermons about the superficiality of our materialistic, hedonistic lifestyles. I like it that way. Of course, the day when everybody confuses “Arab” with “Muslim” and “Muslim” with “fundamentalist”, then any criticism of the latter will backfire on the former. That is why we must keep the distinctions clear.

And to keep these distinctions clear, we must begin by facing the fact that fundamentalism is growing dangerously and killing viciously. Among its victims, the large majority are Muslims who would surely not want to be confused with their killers. So I return now to the question: what is the cause of the rise of fundamentalism?

A friend told me that it was “the West bombing Muslim countries”. I am deeply suspicious of a statement that includes two sweeping generalizations and is reminiscent of Samuel Huntington’s theory of the “clash of civilizations”: the western world vs. the Muslim world. The only difference between George W. Bush and a leftwing stance would be that whilst Bush sided with the western world, the leftwing activist sides with the Muslim world. But to reverse Huntington’s view is a perverse way of confirming it. So let us try to address the issue otherwise.

It is obvious that the rise of fundamentalism is intertwined with the complex series of tragedies that unfolded from colonialism to the present times, including the Israel/Palestine conflict. Yet I think we should recognize one thing. Just as the Christian religion caused an enormous lot of problems in the West for centuries, problems which were not always peacefully resolved, Islam has caused enormous problems in the Muslim world to a lot of people, too. Anywhere in the world, the space for individual rights has always had to be opened by rolling back religion a few miles. And this is something that the Muslim world has begun doing as early as the nineteenth-century, with difficulties not dissimilar to those experienced in the Christian world – for those who would like to explore the parallel, I recommend reading Sami Zubaida’s excellent book Beyond Islam.

Few people even know today that there was a period, beginning in the mid-ninetieth century to the mid-twentieth century, called the Nadha (Rebirth, or Renaissance), which saw a wide-ranging process of secularisation from Morocco to Turkey. Few people care to remember that, in the 1950s and 60s, women wearing the veil were a small minority in Tunis, Algiers and even Cairo. This does not mean that they were not Muslims, mind you. Just as in the West, where a lot of Christian girls started having sex before marriage or taking the pill, principles were evolving, with some inevitable tensions.

Much as it offends the Edward Saïd vision of cultures as bound to devour or be devoured, the Nadha was fuelled by ideas developed by European thinkers and enthusiastically endorsed by local students and intelligentsia – and before you accuse me of Western paternalism, let me stress two things. First, “ideas developed by European thinkers” are not “western ideas”. The anti-colonial movement referred to Marx, Freud and Robespierre, who had – and still have – fierce critics in the West. Second, at the very same time as the anti-colonial movement was drawing inspiration from the history of struggles in Europe, Claude Levy-Strauss was transforming the Western understanding of civilization by studying other cultures, just as Leibniz had extensively studied Chinese language, law and politics in his quest for Enlightenment. Peoples are neither homogeneous nor self-enclosed units: within peoples, people organize themselves and oppose themselves around principles and ideas.

It is on the ashes of the Nadha that fundamentalism as we know it emerged. I say “emerged”, because we should not be fooled by the fundamentalists who claim to restore Islam in its original purity. The ideology they promote – literal, violent, legalistic, narrow-minded, other-worldly – is a radical novelty in the history of Islam. It is the dramatic perversion of a culture. So how did such a perversion take place? This is where the story gets complex – more complex than that of the West vs. the Muslim world.

Anti-colonial movements in France’s former colonial empire (in Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco but also in Egypt) were secular (which of course does not mean that their members were atheists): they intended to create modern nation-states independent from the tutelage of Western exploiters. Thus in Algeria, the Front de Libération Nationale was fighting for the creation of a Democratic And Popular State of Algeria (note the distinctly communist touch). Yet the chaos that emerged during and after independence wars (for which the West clearly has a serious responsibility) provided an excellent opportunity for fanatics of all sorts, who had deeply resented the evolution of their countries, to return to prominence with a vengeance. Thus in Algeria, an extremist wing that had already subverted the FLN during the war eventually came into power after decades of political and economic instability, only to unleash atrocious violence. I have friends of Algerian origins who deeply resent to this day the fundamentalists who robbed them of their secular state and persecuted them to the point that they eventually migrated to France. I am not an expert on “the Muslim world” – if such generalization even makes sense – but I think a similar sort of process took place in many other countries.

So France is home today to many Arabs, some of them Muslims, who were chased away from their home country by fundamentalists as early as the 1960s. They were exposed to racism of course, especially in the workplace – it’s the story that goes back to the Middle Ages of workers who fear the threat of outsiders – and also bullied by the police and treated like second-class citizens. They fought for equality and justice, with the support of many on the left of the political spectrum, for instance during the 1983 Marche des beurs. Believe it or not, none of the protagonists of the march were making religious claims; they were not walking as Muslims but as French citizens who demanded that France truly provides them with Liberté, Egalité and Fraternité.

The spirit of the Marche des beurs is that of Charlie Hebdo: justice for all citizens, including migrants and minorities. Now let me fast forward. Last year, a film was produced, commemorating La Marche des beurs. The producers asked famous rappers to collectively record a promotional number. One of the rappers threw in the verse: “I demand a Fatwa on the dogs at Charlie Hebdo”. He also contrasted “our virtuous veiled girls” with “the make-up wearing sluts”. Yet there were many women in the Marche; none of them were taking a religious stance and few of them were wearing the veil. How could a secular movement for equality be rewritten in religious terms? This raises the question of the rise of fundamentalism in France.

Let us be clear: fundamentalism is not caused by immigration from Muslim countries. It is very easy to demonstrate this: Muslims migrated in France as early as the 1950s and the issue of fundamentalism only arose in the last fifteen years. Moreover, among the young men who enlist to fight for Daesh, many are actually disenfranchised white youth with no familial links to Islam. Fundamentalism is something new, that exercises a fascination on disenfranchised French youth in general – not on Muslims in general. In fact, the older generation of French Muslims is terrified by the phenomenon. After the killing of Charlie Hebdo, Imams demanded that the government take action against websites and networks propagating fanaticism.

That the emergence of fundamentalism is posing serious problems to Arabs also sheds an interesting light on the law banning the hijab – a law that is routinely mentioned as a proof of France’s anti-Muslim bias. I do not have a definite opinion on this law. I was, however, stunned when I read a very angry article by a writer I admire, Mohamed Kacimi. The son of an Algerian Imam, deeply attached to his Muslim culture yet also fiercely attached to secularism, Mohamed Kacimi lashed out angrily at white, middle-class opponents of the law, who focused on the freedom of Muslim women to dress as they please. They were not the ones, he said, who had their daughters in the suburbs called prostitutes, bullied and sometimes raped for the sole reason that they chose not to wear the veil – let us remember that many Muslim women do not consider wearing the veil as compulsory: again, we have here Muslims being persecuted by fundamentalists.

France has a long tradition of secular Islam, fully compatible with the laws of the Republic, but at war with fundamentalists. In the nineties, the Paris Imam was shot by fanatics whose violence he denounced; more recently, the Imam of Drancy, who expressed displeasure with Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons but firmly denounced the fatwa issued against them by Al Qaida, was himself condemned to death by the terrorist organization and is living under the protection of the police.

So the question is: how has a fraction of the French youth (of either white, black or Arabic origin) become so responsive to fundamentalism? The answer to this question cannot be directly traced back to “the West bombing Muslim countries”. I think it has primarily to do with the complete failure of the Republic to deliver on its promises of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité. Here, there is an important point to make.

I often read in the English press, or hear from British friends, that French laïcité is a “foundational myth” – as if France lived under the illusion that religion could be eradicated once and for all. This has nothing to do with laïcité properly defined. Laïcité does not deny anybody the right to express their religious beliefs, but it aims to found society on a political contract that transcends religious beliefs which, as a result, become mere private affairs. The beurs who marched on Paris in 1983 were performing a laïc demonstration. They were not the only ones to demand that the Republic be true to its own principles. In a beautiful book titled La Démocratie de l’Abstention, two sociologists trace the heartbreaking story (at least it breaks my republican heart*) of how the French citizens who arrived from the former colonies vote massively: they are proud of their right to participate in democracy. They try to convince their children to do the same; but the latter are not interested. Decades of social segregation and economic discrimination has made it clear to them that the word ‘French’ on their passport is meaningless – there is no equality, no freedom and clearly no fraternity.

The process of disenfranchisement was gradual. Riots in the banlieues started erupting at the turn of the eighties, and gathered pace in the nineties. They had no religious subtext: they were expressions of anger at discrimination and police harassment. Yet the need to belong is a fundamental human need: if French youth of Arab descent could not feel that they belonged to France, what would they belong to? La Démocratie de l’abstention describes how the conflict between Israel and Palestine – which had been going on for decades already – suddenly caught the imagination of the youth: it was their Vietnam, their cause. They had found their brothers overseas. When, in the 2009 European elections, a bunch of crazed conspiracy theorists launched an anti-Semitic party which had strictly nothing to do with Europe or with the issues that these youth faced, they registered high votes in many suburbs. And as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict itself degenerated from a political conflict into a religious conflict, so did the French youth begin to read the world in religious terms.

Youth is the age of self-sacrifice and revolutionary dreams. In the sixties, young middle class Frenchmen who felt alienated from their conservative milieu idolized Mao’s cultural revolution – no less nihilist than Islamic fundamentalism –, dreamed of throwing bombs and sometimes did so. But this case is different. The middle-class Maoists belonged to a privileged class. They were highly educated. They had the intellectual, economic and social means to move out of their nihilist craze and back into the world. The disenfranchised, ostracized youth are an easy target for indoctrinators of all sorts. Their world-view becoming ever more schematic, they endorsed a West Vs Muslim grid that apparently made some of them incapable of recognizing that a newspaper such as Charlie Hebdo, who was standing with Palestine, for ethnic minorities, for equal rights and justice, was on their side – a precious ally: the sole fact that Charlie Hebdo had poked fun at their faith was enough to make them worthy of death.

And yet perhaps this narrative (which, be reassured, is nearing its end) helps you understand what Charlie Hebdo was trying to do. It was precisely trying to defend the republican ideals whereby it is not religion that determines your commitments but justice. It mocked not the religion that Muslims have quietly inherited from their fathers and forefathers, but the aggressive fundamentalism that demands that everybody defines themselves – ethically, politically, geographically – in religious terms. It stressed that a religion that lays a claim to ruling a society is dangerous and, yes, ridiculous, whichever religion it may be – Islam is no sacred cow.

To conclude. I firmly condemn the bombing of Middle-Eastern countries (or any country for that matter) by Western governments. I vote for political parties that condemn it, and I demonstrate against it. I was shocked when such demonstrations were outlawed by the French government – but happy when the same government recognized the Palestinian state. In these demonstrations, I walk with people of all colours, origins and religious creed – we take a political, not a religious stand. And I despair to think that a fraction of the population of my country refuses to regard me as their ally because I am no friend of religions. Being aware of the root causes of the madness that took hold of these young people, I detest politicians who have done nothing to resolve the deliquescence of the banlieues, to fight routine discrimination and control police persecutions. These issues play as big a part in my view in the rise of fundamentalism in the French youth as do events in the Middle East; that is why, had I been in France today, I do not know if I would have wanted to march together with Angela Merkel and David Cameron – much less with Netanyahu and outright Nazis such as Viktor Orban.

This is the difficult argument I am having with my French friends: we are all aware of the fact that the attack on Charlie Hebdo will be exploited by the Far right, and that our government will use it as an opportunity to create a false unanimity within a deeply divided society. We have already heard the prime minister Manuel Valls announce that France was “at war with Terror” – and it horrifies me to recognize the words used by George W. Bush. We are all trying to find the narrow path – defending the Republic against the twin threats of fundamentalism and fascism (and fundamentalism is a form of fascism). But I still believe that the best way to do this is to fight for our Republican ideals. Equality is meaningless in times of austerity. Liberty is but hypocrisy when elements of the French population are being routinely discriminated. But fraternity is lost when religion trumps politics as the structuring principle of a society. Charlie Hebdo promoted equality, liberty and fraternity – they were part of the solution, not the problem.

With all best wishes,

Olivier

* It was pointed out to me that, should this article be read by American friends, my use of “republican” might be misleading. By “republican”, I do not mean anything to do with the North American party; I use the term in its French sense – the “république” referring to a secular and democratic Res Publica.