'Liberation from Europe's elites': the growth of populism

There are three articles here: 1) The European, there is a ‘good’ side to the new European populism – democratic accountability; 2) Jobbik’s right-wing populism/antisemitism in eastern Europe; 3) Reuters special report on the spread of Jobbik ideology, including links with BNP. Plus Notes and links.

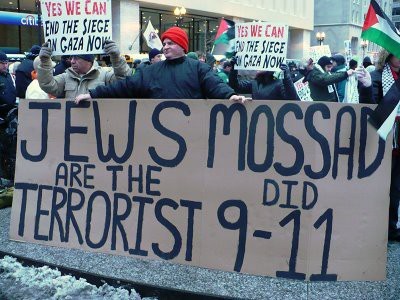

Far-right protest march, Warsaw 2013. Photo by Kacper Pempel / Reuters.

Populists are the predators of European democracy – and the only hope to revive it.

Christina Liang, The European

May 01, 2014

Recent high-profile warnings of a populist backlash in the May 2014 EU parliamentary elections have given birth to several debates as to whether or not populism is a threat to, or an opportunity for, building a stronger European Union.

Several high level officials, including former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta, European Commission President José Manuel Barroso and European Parliament President Martin Schultz, have warned voters that the populist radical right groups have the potential to prevent Europe from functioning and could potentially put it on “life support.”

Populists are gaining strength

Despite a recent period of calm, Europe is still deeply affected by the economic and social crisis. Across Europe people are protesting and banks have defaulted and closed. While some far-reaching governance changes have been pushed through to save financial markets, disputes over market packages and conditionality have divided political parties and sometimes even entire countries. Much of Europe remains in a sustained period of stagnation and current levels of unemployment are unparalleled in post-Second World War history.

Anti-EU parties have seized this opportunity to exploit the dramatic fall in the popular support for European integration. Anti-European sentiment is on the rise in Europe. Across Europe right-wing and nationalist parties are gaining strength. In France, opinion polls gave Marine Le Pen, the leader of the Front National (FN), 24% of the vote, which could potentially make this right-wing populist party the biggest French delegation in the European Parliament.

Liberation from the monster

Some argue that anti-EU populists have never had it so easy. Geert Wilders, the charismatic leader of the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV), announced his party’s collaboration with Marine Le Pen’s Front National in November 2013. The two parties announced that they will join hands in the upcoming European elections as the Alliance of Freedom. According to Wilders, the Alliance’s objective is “Liberation from Europe’s elites. Liberation from the monster from Brussels….”

Those who fear the worst argue that populist parties will win big, reaching as much as 25 percent of the votes in the upcoming elections, raising alarms about European stagnation or even a shutdown similar to the one experienced in the United States a few months back. While such fears may be overblown, Geert Wilder’s plan to build a populist radical right faction within the EU Parliament is already having an effect.

In Europe’s discussions about a new asylum policy following the Lampedusa disaster, Manfred Weber, a member of the Christian Social Union (CSU) said: “In view of the polls that predict up to 30% for Euroskeptics in the new parliament, a more liberal immigration policy can currently not be introduced because it would give the extremists even more of a boost.”

Supporters of Hungary’s anti-Semitic Jobbik party rally in Budapest, 2013. Jobbik can be translated as ‘reform’ or ‘progress’; it is formally ‘the movement for a better Hungary’.

Nonetheless, for all its ills, populism serves an important function. While mainstream parties may dislike the arguments and style of populism, the alternative – anti-democratic political extremism – is much worse. In Eastern Europe, the more extreme variant of anti-European populism has reinforced nationalism and fostered racism and xenophobia. In particular in Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, extreme right militias have been terrorizing Roma minorities as well as homosexuals. In Greece, neo-Nazis from the “Golden Dawn” have attacked immigrants, homeless people, and LGBT people.

Populism can increase democratic accountability

Many assume that populism is bad for democracy; however, the elections can also trigger a new impetus through which Europeans begin to believe that the EU is worth fighting for. In its annual report, the World Economic Forum identified among the top ten trends of 2014 a lack of values in leadership; widening income disparities; and the diminishing confidence in economic policies. The report argues that “a generation that starts its working life in complete hopelessness will be more prone to populist politics.” Accordingly “there’s a disassociation between governments and the governed.” These trends should not be ignored.

UKIP says it all to the angry and impotent

Populism can address these sentiments by allowing the ideas and interests of more marginalized sections of the electorate to be integrated into the political process. Populism can increase democratic accountability and can force politicians to be more transparent and less corrupt. It can provide an ideological bridge that supports the importance of building political coalitions. Populism can also give a voice to groups that do not feel represented by the elites and can help put forward topics that are important to the silent majority.

The EU must fight

The EU must understand that the rise of populist groups indicates that Europe can no longer govern as it has in the past, and it can not afford to ignore the real social and political aspirations of its citizens. It must demonstrate that it is changing. In order to do this, it must make efforts to bring in a new generation of politicians who are more transparent and more adept at governing.

There needs to be more efficient EU-wide institutions. The EU must be able to speak to its citizens and show projects that will wield real growth. Most importantly, it must fight against youth unemployment by helping young people who have graduated to go directly into internship or apprenticeships that will lead to jobs. Europe must also continue to fight against protectionism and to support the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. An effective Trans-Atlantic market can help spur growth and prevent future stagnation of Europe’s markets.

An important wake-up call

While populist radical-right groups seem threatening, they are ill-suited for the deal-making and horse-trading required for effective multi-lateral diplomacy in Europe and the world. Voters flocking to support these firebrands within their nation states would probably recoil in horror if they attempted to join the European Parliament and attempted to build coalitions with other like-minded members.

So it is unlikely that these new populist radical-right groups will be able to disrupt the day-to-day functioning of the European Parliament, or the Parliament’s relationship with other European institutions like the Council or the Commission. However, their rise is an important wake-up call to take action and to do it now.

Dr Christina Schori Liang has been working in the field of security policy for the past 20 years. She began her career at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies in Washington D.C., and in 1996, moved to the Geneva Centre for Security Policy. In 2007, she started teaching the GCSP’s core training programmes on terrorism, organized crime, political extremism and homeland security issues. In 2012, she became the Co-Director of the New Issues in Security Course (NISC) and in 2013 she was appointed Director of the NISC.

Golden Dawn organises popular protest against road tolls in Greece, May 2013. One of its MPs, Ilias Kasidiaris, sports a swastika tattoo and once read from “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” in Greece’s parliament.

In parts of Europe the far right rises again

By Sonni Efron, OpEd, LA Times

May 08, 2014

As Europe marks the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, the war that destroyed Old Europe, far-right parties are gaining ground across New Europe.

Most of the far-right parties are pro-Russia, opposing U.S. and European Union efforts to isolate President Vladimir Putin for his intervention in Ukraine. They are expected to do well in the May 25 European Parliament elections.

Human rights groups counted at least 320 victims of racist violence in Greece last year alone.

Last month, I traveled to Hungary and Greece, where the neo-fascist movements are strongest. In Hungary, the extreme-right Jobbik party won 1 in 5 votes in last month’s parliamentary election. In Greece, even as the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party is being prosecuted by the government as a criminal organization, it remains the fourth-largest political party in the country. Golden Dawn lawmaker Ilias Kasidiaris, who sports a swastika tattoo and once read from “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” on the floor of Parliament, is running for mayor of Athens.

Both parties deny being inherently anti-Semitic or anti-Roma, but their symbols and rhetoric suggest otherwise. Party leaders are unapologetically hostile to LGBT rights, and Golden Dawn is vehemently anti-immigrant. And in both Greece and Hungary, many voters appear to be either overlooking the neo-fascist message or embracing it.

Despite international condemnation of Jobbik’s anti-Semitic, anti-Roma vitriol, support for the party rose from 18% in the 2010 elections to 21% last month. Among those reelected to office was a Jobbik member of parliament who demanded that the government draw up a list of Jews in official positions because they posed a “national security risk.” Another winning candidate claimed that “the Gypsy people are a biological weapon” of the Israelis who have “occupied” Hungary. These are not idle words in a country where Roma have been terrorized or killed in organized attacks.

The Hungarian media have reported that Jobbik is toning down its rhetoric to appeal to a wider range of voters. But covert anti-Semitic messages still hide in plain sight. One Jobbik advertisement shows a wholesome family eating at a dinner table in front of a bookshelf filled with works by notoriously anti-Semitic writers. I heard Jobbik candidates on the stump in a working-class neighborhood of Budapest complaining about “international bankers” and griping about how telling “a Jewish joke” was the worst crime a Hungarian politician could commit nowadays.

Meanwhile, Hungary’s authoritarian prime minister, Viktor Orban, has deepened ties with Moscow, signing a $13-billion deal for Russia to build and finance a nuclear power plant in eastern Hungary. And he has outraged the Jewish community, including Holocaust survivors, by pushing ahead with a World War II memorial that minimizes the role of Hungarians in the Holocaust and places all the blame on the German invaders.

In Greece, the government is locked in a remarkably belated battle with Golden Dawn. In 2010, the party was on the margins, winning only 0.2% of the vote. But then, as the economy collapsed, gangs of neo-Nazi thugs began terrorizing migrants, including traumatized Syrian refugees, and support for Golden Dawn surged. In 2012, the party claimed 7% of the vote and 17 seats in Parliament, a victory Golden Dawn leaders reportedly took as approval for “protecting” Greeks from a flood of immigrants.

Scars left on an African migrant’s back by neo-Nazi attackers in Greece. Photo from Medicins du Monde

A migrant worker from Africa was attacked by thugs who carved Golden Dawn’s insignia into his back, an Egyptian was tortured, and a Pakistani was killed bicycling to work. Human rights groups counted at least 320 victims of racist violence in Greece last year alone. But it was not until September’s slaying of a Greek citizen, the anti-fascist rap musician Pavlos Fyssas, that the government moved against Golden Dawn, arresting most of its senior leadership and alleging that it is a criminal organization engaged in offenses ranging from weapons possession to murder.

The party’s “Fuhrer” and several others remain in jail, while two special magistrates investigate. Yet a defiant Golden Dawn is still advancing candidates for both local and European Parliament elections this month, and some of its alumni say they will stand under a new name, National Dawn. A court is expected to rule on who can run. And there is growing evidence that Golden Dawn has benefited from the tolerance, if not support, of elements of the ruling New Democracy party, the police, the Greek Orthodox Church and the military.

In both Greece and Hungary, the far right is clearly growing in popularity. The question now becomes the degree to which voters in these countries and across Europe are becoming accustomed to the rhetoric of the neo-fascist movements, and the extent to which the ruling parties pander to right-wing voters. It now appears that far-right candidates may win enough seats in the European Parliament to form a bloc that could corrode the fundamental premise of the EU: an alliance for shared peace and prosperity built on respect for territorial integrity, strong democratic institutions and a commitment to human rights.

Oddly, the best hope for a democratic Europe may lie in the traditional disdain of Western European right-wingers for Eastern and Southern Europeans, and squabbling within the far right over which of the national parties are so extreme as to cause an image problem. These internal tensions could prevent the European neo-fascists from forming a functional continental alliance — just as in Old Europe.

Sonni Efron, a former State Department official and a former reporter for this newspaper, is a senior fellow at Human Rights First. She is particularly focused on targeting atrocity enablers in Syria, and on Internet freedom and digital free expression issues.

Special Report – From Hungary, far-right party spreads ideology, tactics

By Marcin Goettig and Christian Lowe, Reuters

April 09, 2014

WARSAW –In a rented public hall not far from Poland’s parliament, about 150 people gathered one afternoon late last year to hear speeches by a collection of far-right leaders from around Europe.

The event was organized by Ruch Narodowy, or National Movement, a Polish organization that opposes foreign influences, views homosexuality as an illness and believes Poland is threatened by a leftist revolution hatched in Brussels.

Chief attraction was Marton Gyongyosi, one of the leaders of Hungarian far-right party Jobbik.

In a 20-minute speech, Gyongyosi addressed the crowd, mostly men in their thirties and forties, as “our Polish brothers,” and railed against globalization, environmentalists, socialists, and what he called a cabal of Western economic interests.

Poles needed to resist the forces hurting ordinary people, he said, before urging “regional cooperation between our countries.”

Anti-Islam protests in Lincoln, UK, organized by the East Anglian Patriots, June 2013.

It is a familiar rallying cry. Far-right groups have emerged or grown stronger across Europe in the wake of the financial crisis, and they are increasingly sharing ideas and tactics. Reuters has found ties between at least half a dozen of the groups in Europe’s ex-Communist east. At the network’s heart, officials from those groups say, sits Jobbik.

The party won 20.54 percent of the vote in Hungary’s parliamentary election on April 6, up

from the 15.86 percent it won in 2010, cementing its status as by far the largest far-right group in Eastern Europe.

From its strong base at home, Jobbik has stepped up efforts to export its ideology and methods to the wider region, encouraging far-right parties to run in next month’s European parliamentary elections, and propagating a brand of nationalist ideology which is so hardline and so tinged with anti-Semitism, that some rightist groups in Western Europe have distanced themselves from the Hungarians.

The spread of Jobbik’s ideology has alarmed anti-racism campaigners, gay rights activists, and Jewish groups. They believe it could fuel a rise in racially-motivated, anti-Semitic or homophobic street attacks. Longer-term, they say, it could help the far-right gain more political power.

In a statement sent to Reuters, Jobbik said that it hoped the people of central and eastern Europe would unite in an “alliance that spreads from the Adriatic to the Baltic Sea,” to counter what it called Euro-Atlantic suppression.

Jobbik rejected any link between the growing strength of radical nationalists and violence. “Jobbik condemns violence, and its members cannot be linked to such acts either,” it said.

SPREADING IDEOLOGY

The day after Gyongyosi’s speech last November, Jobbik’s leader, Gabor Vona, addressed another rally in a Warsaw park.

“The path to final victory involves a million small steps,” he told the crowd, through a translator. “You should take up this challenge. Take part in the European elections.”

The founding congress of Ruch Narodowy in December 2013.

The crowd chanted: “Poland and Hungary are brothers!”

As they marched through the city earlier that day, some of the Polish participants fought pitched battles with police and set fire to a rainbow sculpture erected as a symbol of diversity.

Poland is not the only example of Jobbik’s regional outreach. Far-right groups in Poland, Slovakia, Croatia, and Bulgaria told Reuters they have ties with fellow parties in several countries in the region. Jobbik sat at the center of that web, the only one with contacts with all the parties.

Nick Griffin, now in talks with antisemitic Jobbik, leads an anti-Islam march, June 2013. Photo by Peter Marshall/Demotix/Corbis

Nick Griffin, leader of the British National Party (BNP), one of the few far right parties in Western Europe with close relations with Jobbik, said the Hungarian party is the driving force behind efforts to forge a far-right coalition.

Other groups say they admire the party because of its success in Hungary and its organizational muscle.

Jobbik appears to operate on a shoestring. It has an annual budget of $2.34 million, according to the Hungarian state audit office, most of it from a state allowance to parties in parliament. Jobbik denies giving financial aid to other groups, but it can afford its own staff, travel, and facilities – all factors that enhance its influence.

“Jobbik is a market leader of sorts,” Gyongyosi said. “There are shared values, and the way Jobbik grew big, why could the same thing not happen elsewhere?”

“AGAINST THE DICTATES OF BRUSSELS”

Broadly speaking those shared values include a strong opposition to Brussels, a dislike of immigrants, and a suspicion of Jews and of the Roma, an ethnic minority who number about 10 million in Eastern Europe and who have faced centuries of discrimination.

Hromoslav Skrabak, leader of 19-year-old Slovakian group Slovenska Pospolitost, has argued for racial segregation and “humanitarian” methods to reduce Roma fertility. Skrabak said his group cooperates with far-right groups in Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Serbia to jointly fight “against the dictate of Brussels,” and to spread the idea of pan-Slavism, a union of ethnic Slavs.

Frano Cirko, a member of the Croatian Pure Party of Rights, said cooperation between far-right groups helped take on “neo-liberal” capitalism, which he said threatened national values in Europe and made it too easy for foreign firms to buy Croatian companies.

Angel Dzhambazki, deputy leader of Bulgaria’s VMRO, a movement that has its roots in the late 19th century and was revived in 1990, said its “close cooperation” with Jobbik and a Croatian group had helped it grow. “We invite them to participate in our meetings, and at the same time we take part in events organized by them.”

VRMO is in the process of forming a coalition with a new populist party called Bulgaria Without Censorship. A poll by Bulgaria’s Institute of Modern Politics showed that, together, the parties would have 5.6 percent support for the European Parliament election, putting them third and giving them a chance of winning one of Bulgaria’s allocation of 17 seats. The elections for the European Parliament take place on May 22-25 in all 28 member states of the bloc.

WESTERN FRONT

Jobbik has had less success in Western Europe, where more established nationalist parties reject its anti-Semitic views. In 2012, Jobbik’s Gyongyosi told the Hungarian parliament that Jews were a threat to national security and should be registered on lists. He later apologized and said he had been misunderstood. But parties such as the Dutch Party of Freedom, which is staunchly pro-Israel, and France’s National Front, which has sought to move away from its anti-Semitic past, are both wary of the Hungarian group.

Jobbik’s principal ally in Western Europe is the British National Party. Griffin, its leader, said the BNP and Jobbik were working together on building a functioning bloc of nationalists within the European Parliament.

“I would say probably I do more of the work in eastern and southern Europe than they (Jobbik) do, whereas they tend to concentrate on the center and the east,” Griffin said in a telephone interview.

Opinion polls in Britain suggest the BNP will lose the two seats it currently holds in the European parliament.

One far-right party that polls predict will win seats in Brussels is Greece’s Golden Dawn, which says it wants to rid the country of the “stench” of immigrants. But Jobbik told Reuters Golden Dawn was “unfit” for the Hungarian party to cooperate with. Golden Dawn spokesman Ilias Kasidiaris said there was no official cooperation with Jobbik.

Cas Mudde, assistant professor at the School for Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia in the United States, said that Jobbik is driven in part to look for allies “to show that it is not some kind of marginal phenomenon. There are two ways to do that: You can do it nationally, which is very hard, or you can do it internationally by saying: ‘Look, we have friends all over the place.'”

“THIS IS DANGEROUS”

Last May, the World Jewish Congress (WJC) urged European governments to consider banning neo-Nazi parties that threatened democracy and minority rights. The WJC met in the Hungarian capital Budapest to underscore its concerns about Jobbik.

Rafal Pankowski from Never Again, a Polish anti-racist association that tracks cases of racially motivated violence, said he feared that Jobbik’s efforts to spread its tactics and ideology could lead to more violence against minorities.

“This is dangerous,” he said of Jobbik’s international influence. “If similar groups in other countries copy this model … then the situation might worsen.”

Robert Biedron, a gay member of the Polish parliament, said Polish far-right activists ran a website called Red Watch where they posted pictures and personal details of people they described as “queers and deviants,” as well as lists of left-wing activists and Jewish academics.

Biedron reported to police that he was beaten up in Warsaw at the end of February in what he believes was a homophobic attack.

Biedron said he did not expect Ruch Narodowy to win seats in this year’s European election, but the Polish party’s support was rising, and it had a chance in next year’s Polish parliamentary polls. If that happens, he said, it will use parliament to promote its rhetoric “based on hate for others.”

Jobbik’s network-building has been most successful in Poland in part because Poland and Hungary have no historical claims on each other’s territory, an issue that has often hindered cooperation between Jobbik and nationalists from other neighbors.

PARAMILITARIES

On a sandy riverbank in the shadow of a bridge over the river Vistula, members of the paramilitary arm of Ruch Narodowy rehearsed for their role as stewards before November’s rally in Warsaw.

Some looked like the stereotype of far-right skinheads. Others were middle-class professionals. One showed up in an Audi saloon, another in an expensive sports utility vehicle. The unit’s leader, Przemyslaw Czyzewski, said several members were lawyers.

A diagram of the organization’s structure showed it had a military-style hierarchy, and units called “choragiew”, a word which was used in the past to describe Polish cavalry formations.

Explaining why he decided to join the unit, one man said he wanted to defend Polish values under threat from foreign influences. “I finally had to do something,” said the man, in his thirties, who did not give his name.

The group denies it takes its inspiration from Hungary, but it has striking similarities with Jobbik’s paramilitary wing, called “Magyar Garda,” or Hungarian Guard. In 2008 a court ruled that Magyar Garda threatened the dignity of Roma and Jewish people. The group disbanded but was quickly replaced by a similar organization.

Robert Winnicki, the bookish, bespectacled 28-year-old leader of Ruch Narodowy, has described homosexuality as “a plague” and talked of creating a “new type of Pole” disciplined enough to take on the country’s enemies.

He told Reuters that the aim of his movement’s contacts with foreign peers was to “exchange experiences, learn from each other.”

Winnicki traveled to Hungary in March last year to address a rally of Jobbik activists.

“Inspired by your example, we are organizing a national movement today in Poland,” he told his Hungarian hosts, according to a published transcript.

“An army is quickly growing in Poland which soon, on its section of the front, will join the battle that you are conducting. And together we will march to victory.”

Additional reporting by Marton Dunai in Budapest, Renee Maltezou in Athens, Tsvetelia Tsolova and Angel Krasimirov in; Sofia, Robert Muller in Prague, and Zoran Radosavljevic and Igor Ilic in Zagreb

Notes and links

Anti-Muslim violence: A wakeup call for European governments, EU Observer, July 2013If you can read Polish, and have the stomach for it, here is a very anti-semitic stream from Poland’s Ruch Narodowy

Europe’s Anti-Muslim Racism, Ahmed Moor, Huffington Post, May 2010.

Far-right Jobbik Party Protest against ‘Israeli Conquerors’ in Hungary, IBT, May 2013

Growth of extreme right in Europe round-up world socialist website

Right-wing populists on the rise, round-up of reports, eurotopics, May 2014.

Why Is the Far Right Growing? This 1995 posting from Solidarity (US) identifies factors in what was then the beginning of a new trend.

Australia’s far-right fringe groups must not be allowed to become mainstream Antony Loewenstein, May 2014