EU too divided for role in MidEast

x

The PM of Israel shares a platform with Hungary’s antisemitic and anti-immigrant Viktor Orban who said the “invasion” threatening Europe must be stopped, and that Hungary’s and Israel’s strong national identity and their fight against subversive forces, namely Near-Eastern terrorism, connects the two countries. For a withering critique of Netanyahu’s wooing of the V4*, see Hungarian Spectrum

Occupation and Sovereignty: Renewing EU Policy in Israel- Palestine

Policy discussion document from the think-tank, the European Council on Foreign Relations [not an EU body]

NOTE. The numbers of the footnotes have been kept in so you can look them up, but their content not included for reasons of length.

By Hugh Lovatt, ECFR

December 21, 2017

SUMMARY

Developments in 2017 have brought into focus the one-state reality taking hold in Israel-Palestine. This will have unavoidable repercussions for the EU and its member states, underlining the urgent need for bolder and more decisive EU action.

The EU must take seriously the implications of an emerging one-state reality for EU-Israel relations and EU policy more generally. This should not be about discarding the two-state solution but rather acknowledging that an immediate course correction is required to avoid a fully-fledged one-state reality of perpetual occupation and unequal rights.

Despite the absence of credible US leadership, the EU and its members have the power to save the two-state solution. If they are serious about this, they must act now – and with determination. This includes supporting on-the-ground Palestinian sovereignty-building strategies, cementing the contours of a final status agreement, and leveraging Israel’s growing relations with Gulf Arab states to make meaningful Israeli steps towards de-occupation.

Introduction

Developments in 2017 have brought into focus the one-state reality taking hold on the ground in Israel-Palestine, and the consequences this will have for all concerned. Israeli actions have steadily eroded the territorial basis for a two-state solution and undermined attempts to reach a peace agreement with the Palestinians. Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and efforts to distance himself from the two-state solution have only accelerated this shift towards a one-state reality.

The cementing of “a one-state reality of unequal rights, perpetual occupation and conflict” – in the words of Federica Mogherini, the European Union’s high representative for foreign affairs and vice-president of the European Commission – require Israel to choose between maintaining either its democracy or its Jewish political majority, in the extent to which it grants rights to the almost five million Palestinians under its military control.[1] For Palestinians, a one-state reality may eventually lead to political empowerment. But, until Israel ends its unlawfully prolonged occupation, Palestinians will continue to experience discrimination, territorial dispossession, and open-ended military subjugation in the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT).

All of this has repercussions for the EU and its member states, underlining the extent to which EU policy has fallen out of sync with trends on the ground and in the negotiating arena. Worse still, intra-European divisions and the EU’s relationship with Israeli settlements is further weakening the two-state solution the EU has long strived to achieve. During the last 25 years of its engagement with the Israel-Palestine conflict, the EU has (despite its many efforts and best intentions) increasingly contributed to a reality that is at odds with Israelis’ and Palestinians’ desire for self-determination.

This is not to say the EU has not had successes or policy achievements. In fact, it can learn from, and take pride in, several of its most effective policies. The EU has played a key part in promoting and sustaining international support for a two-state solution predicated on Palestinian statehood in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza. EU measures designed to differentiate between Israel and Israeli settlements in the OPT have helped remind the international community of the pre-June 1967 Green Line as the basis for a Palestinian state and, at times, have forced the Israeli authorities to adapt their practices accordingly. The EU has also reinforced international adherence to non-recognition of Israel’s sovereignty in the OPT, and international reaffirmation of the illegality of Israeli settlements there.

The EU can also claim credit for keeping the international spotlight focused on Israeli violations of international law, and for inspiring the United Nations to enshrine EU policy language on the conflict in a December 2016 UN Security Council resolution.[2]Finally, EU financial support has helped make Palestine ready for statehood and gone some way towards protecting vulnerable Palestinian communities in Area C of the West Bank from coercive actions by Israel.

Yet, the EU should also learn from – and seek to address – its failures and inadequacies. It has often failed to translate its rhetorical and financial support for Palestinian sovereignty into concrete political action that can fulfil its vision of a two-state solution. For all its political goodwill and financial investment, the EU has in practice incentivised Israel’s continued commitment to prolonged occupation of the OPT and obstructed steps towards Palestinian sovereignty.

Regardless of the EU’s foreign policy scorecard, only Palestinians and Israelis can make decisive progress towards peace. However, Israel’s government and public opinion show no immediate indication of ending the occupation or allowing for the creation of a fully sovereign and contiguous Palestinian state based on the Green Line. For its part, the Palestinian liberation movement has become atrophied and fragmented, lacking the ability to galvanise popular support for a new set of strategies to challenge the occupation. If anything, these two trends lead away from a two-state solution.

The saviour of the two-state solution will not come from Washington. The EU has stepped back and given the new US administration room to relaunch the Middle East Peace Process (MEPP), reasoning that even a process that goes nowhere is better than nothing. By now, though, it is likely clear to the EU that the Trump administration is leading both sides over the edge of a cliff.

Despite the absence of credible US leadership, an effective Palestinian liberation strategy, and Israeli moves to end the occupation, the EU and its members have some power to save the two-state solution. If they are serious about doing so, they must act now – and with determination.

Mogherini has spoken of the need for greater EU engagement to solve the conflict. But this cannot equate to doubling down on the current failed approach. Instead, the EU should chart a new policy course that helps preserve the normative and physical space needed for a two-state solution, leverage Israel’s growing relations with Gulf Arab countries, and build the conditions necessary for a meaningful resumption of Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations. At the same time, the EU should give serious thought to how its engagement with Palestinians can develop from state-building to on-the-ground sovereignty-building, and how it can cement the contours of a final status agreement.

The EU’s policy review

During an informal meeting of EU foreign ministers in Tallinn in September 2017, Mogherini announced a review of the EU’s modes of engagement with the Israel-Palestine conflict, aiming to better align the EU’s activities and instruments with the goal of achieving a two-state solution.[3]

EU Foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini meets President Mahmoud Abbas at the EC’s External Action HQ in Brussels on October 26, 2015. Photo by Emmanuel Dunand.

The initiative is a welcome, and badly needed, step towards the implementation of a stronger and more effective EU policy on the conflict. But for it to be meaningful, the review must extend beyond a narrow technical evaluation of the modalities of financial assistance for the Palestinian Authority (PA) – as seems to be currently envisaged – by also conducting a technical review of the EU’s relations with Israel to ensure they fully and effectively exclude Israeli settlement entities and activities.

In addition, the EU would do well to undertake a broader policy review that tackles the political and regional context of international peacemaking efforts. It should also assess how the entrenchment of a one-state reality will affect its engagement with the sides.

Dealing with a negative political context

At the core of current diplomatic regression is the failure of the US-led version of the MEPP stemming from the Oslo Accords, which has trapped the EU in a peacemaking model that is unable to deliver a final peace agreement and that entrenches Israel’s prolonged occupation.[4] But a continued desire to give the Oslo-format MEPP a chance to succeed – without tackling the reasons for its continued failure over 25 years – has dissuaded the EU from taking any serious measures to challenge Israel’s prolonged occupation. As such, the EU has become an enforcer of the status quo established by the Oslo Accords rather than an actor that could effectively support strategies to end the occupation and back Palestinian self-determination.

Israel’s shift away from the two-state solution

Behind the long-standing structural failings of the MEPP has been a steady turn to the right in Israeli politics and society, in favour of policies and actions that normalise Israel’s occupation and settlement project. Due to this dramatic shift, pro-settlement positions and efforts to discredit a two-state solution in line with internationally accepted parameters have become mainstream.

a mixture of government illiberalism and right-wing activism has shrunk the political space for Israeli voices critical of the occupation

With the exception of the left-wing Meretz and the Arab-dominated Joint List, Israeli parties – including the centre-left Labor Party – have moved away from the traditional two-state paradigm in favour of a placeholder arrangement that would effectively allow for the consolidation of the settlement enterprise and formalise the one-state reality (or a “Palestinian state minus”), in which Palestinians are granted continued self-rule under Israeli military oversight. And while Labor’s newly elected chair, Avi Gabbay, has indicated that he favours “two states for two peoples”, he opposes attempts to uproot Israeli settlements and holds that Israeli sovereignty over a united Jerusalem is more important than a peace deal.[5]

Meanwhile, a mixture of government illiberalism and right-wing activism has shrunk the political space for Israeli voices critical of the occupation. The Israeli government and the pro-settlement movement have seized upon the rise of illiberalism, anti-Islamism, and far-right politics in Europe and the United States to forge a new set of alliances in their efforts to normalise the occupation, roll back international law, and discredit the liberal order.

US policy regression

Trump has acknowledged that, on the Israel-Palestine conflict, “we cannot solve our problems by making the same failed assumptions and repeating the same failed strategies of the past”. Yet his administration has rolled back positions the US has held for more than a decade and, in doing so, eroded the key tenets of the international community’s approach to the conflict.

In the administration’s first year, the US has reneged on its long-standing commitment to a two-state solution as the goal of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, cast doubt on the legal status of the OPT, and come close to legitimising Israel’s settlements. This was capped by Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December 2017, reversing more than 70 years of US policy. All of these moves run contrary to long-standing EU positions, and in effect “double down on an unmistakable message to [prime minister Binyamin] Netanyahu and settlers that the United States is fully on board with policies that foreclose the two-state solution, including in Jerusalem”, as analyst Lara Friedman put it.[6]

Alongside this, the US Congress and state legislatures have passed legislation that conflates Israel and Israeli settlements, while blacklisting EU companies that deliberately exclude Israeli settlements from their business dealings.[7]

Intra-European divisions

The EU’s capacity to act effectively in support of Israeli-Palestinian peace has been limited by deep divisions between member states and several internal crises, from the United Kingdom’s pending departure from the EU to large-scale migration; from eurozone reform to the rise of illiberal governments in Poland and Hungary.[8]Additionally, European decision-makers confront several external crises that are seemingly more pressing, not least those in its southern neighbourhood. Issues relating to civil wars in Libya and Syria, destabilising migration flows from north Africa, and the fight against the Islamic State group dominate many Europeans’ foreign-policy agenda, pushing the Israel-Palestine conflict further down their list of priorities.

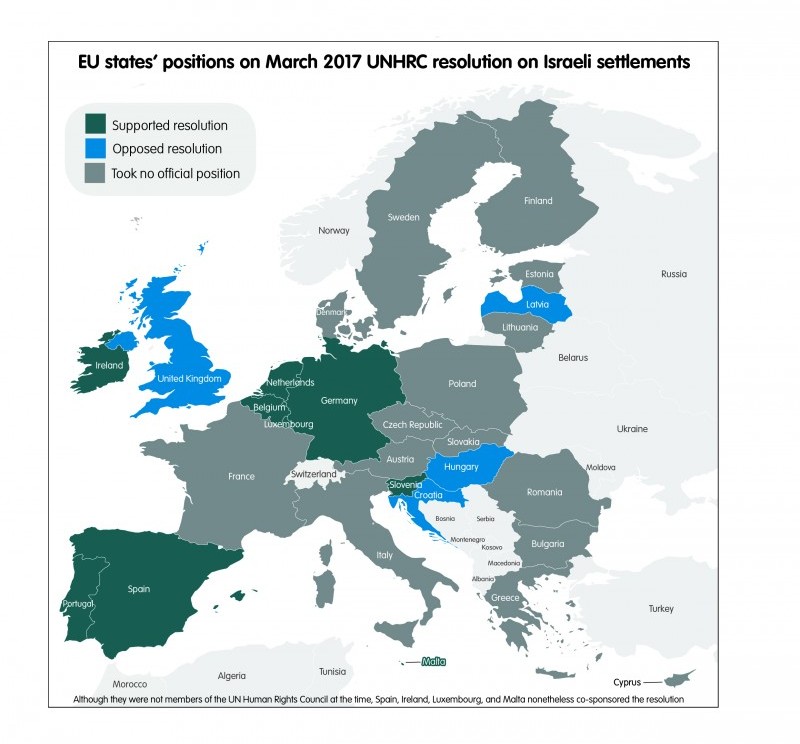

Attempts to advance EU decisions on the MEPP have also been frustrated by internal divisions between states that are relatively sensitive to positions and obligations based on international law (predominantly, those in western Europe) and others that, out of ideology or geopolitics, have effectively defended Israeli actions that violate such law (primarily, those in the east). The UK’s June 2016 decision to leave the EU widened this split, as the country pulled back from EU initiatives and consensus making on the issue, aligning itself with US policy under Trump on several occasions. These divisions played out over – for instance – the March 2017 UN Human Rights Council vote on Israeli settlements.

The result of internal divisions has been inaction in the EU’s main foreign-policy body

Israel has exploited these divisions in its efforts to divide the EU, block the Union’s future decisions, and alter its consensus positions. This was on full display during a meeting in July 2017, when Netanyahu joined the leaders of Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, and the Czech Republic (known as the Visegrád Four) in berating EU policy on Israel, before urging them to help move forward the next meeting of the EU-Israel Association Council (which has been delayed due to a lack of consensus among member states).

The net result has been inaction in the EU’s main foreign-policy body – the European Foreign Affairs Council (FAC), which brings together EU foreign ministers. Despite the unprecedented threat to the two-state solution from the US and Israeli governments, and the deterioration of conditions on the ground in the OPT (particularly the humanitarian crisis in Gaza), there have been no FAC conclusions relating to the MEPP since June 2016. Even a high-profile French peace initiative in begun in early 2016 and the adoption in December that year of UN Security Council Resolution 2334 – which endorsed EU positions such as its differentiation requirement – failed to inspire European action or unity.

Facing new problems

Beyond the long-standing political impediments highlighted above, the EU will have to address a new set of challenges created by shifting politics at the regional and local levels in the Arab world. But, unlike the entrenched issues above, these emerging challenges can be mitigated through effective policy planning.

Fragmenting politics in Palestine and the coming post-Abbas era

Palestinian infighting has laid bare the deep fractures and growing tensions within, and among, Palestinian political factions. Added to this has been the split between the West Bank and Gaza resulting from Hamas’ victory over Fatah in contested legislative elections in 2006. The pursuit of sanctions and no-contact policies targeting Hamas by the international Quartet (comprising the EU, Russia, the US and the UN) exacerbated Palestinian political and geographical divisions. Despite acknowledging the shortcomings of such policies, the EU and its member states have yet to formally alter their position or actively support the stalled, Egyptian-sponsored Hamas-Fatah reconciliation process.

Palestinian leaders and regional actors are steadily positioning themselves for the anticipated appointment of a successor to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. In practice, there are no agreed institutional mechanisms for managing the leadership transition. Abbas’s marginalisation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Executive Committee and Fatah’s Central Committee, along with the broader concentration of power within his person, reduces the ability of the PLO and Fatah to implement a smooth leadership transition. These factors have led to the democratic atrophy of the nascent Palestinian state.

Until now, a narrow focus on technocratic governance and security, combined with a large amount of donor aid, has kept the Palestinian state-building project afloat and the PA stable. But the slow-motion implosion of traditional Palestinian leadership structures could converge with growing popular frustration, the disappearance of diplomatic routes to ending Israel’s occupation, and humanitarian challenges in Gaza to increase Palestinian instability and fragmentation.

A growing belief that the strategy pursued by the Palestinian liberation movement for 25 years has failed will present significant dilemmas for the EU given its deep ties with the PA, particularly once a new generation of Palestinian leaders less wedded to the Oslo-format MEPP and two-state solution emerges.

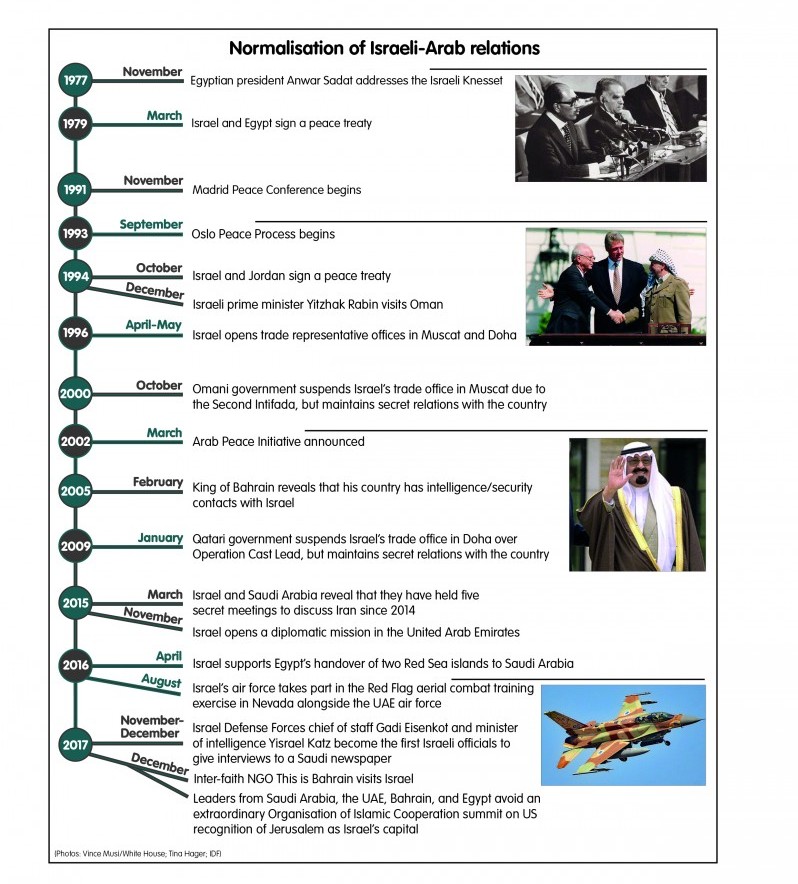

A shifting regional landscape and the erosion of the Arab Peace Initiative

Regional dynamics have put Gulf Arab states such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain on the path to normalising their ties with Israel. In partnership with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the Trump administration has repeatedly spoken of its desire to reach the “deal of the century” on regional peace. Given real Palestinian anger at the administration’s change of position on Jerusalem, it is unclear whether a Trump peace initiative will ever materialise – but, if it does, it will most likely include a regional peace track predicated on speeding up the normalisation of Israeli-Gulf Arab relations.

To be sure, this process is hardly new. It has been discreetly gathering speed since the Arab Spring upheaval in the region and the alignment of Israeli and Gulf Arab interests over their shared antipathy towards Iran and political Islam. Although it remains unclear how far this process can ultimately go without grassroots support in Gulf Arab countries, Israeli-Gulf Arab bilateral relations are expected to continue growing – despite the current fallout over Jerusalem. Indeed, promoting greater economic and political cooperation between Israel and Arab states appears to have supplanted Israeli-Palestinian negotiations as a priority for the Trump administration, according to its new National Security Strategy.[9]

While regional peace is a worthy foreign policy objective, any process of normalisation that comes at the expense of the Palestinian issue – or uses the issue as merely a fig leaf – will bring with it real complications in potential domestic blowback among Arab populations and the erosion of the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative (API), which conditions any normalisation of ties between Israel and the Arab world on an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement. Although the API’s offer has gone unanswered by successive Israeli governments, its conditionality and normative elements are important in pushing Israel towards a lasting peace deal with the Palestinians. The reversal of the API (known as an “outside-in” approach) would convince Israeli politicians and the Israeli public that the country’s foreign relations can be advanced without taking any real steps towards ending the occupation.

Going back to basics

Time to rethink the EU’s approach to Israel?

There remains a clear gap between European discourse and practice in promoting a two-state solution. The EU has been firm in its belief that “the only way to resolve the conflict is through an agreement that ends the occupation which began in 1967, that ends all claims and that fulfils the aspirations of both parties [and that] a one state reality would not be compatible with these aspirations.”[10] Statements by several EU and member state officials have sought to drive home the point that, despite the sides’ strong ties, the relationship between the EU and Israel cannot be fully separated from the spillover caused by the latter’s conflict with the Palestinians.

As Nicholas Westcott, then managing director for the Middle East and North Africa at the European External Action Service (EEAS), pointed out, “there is unfortunately a fly in this ointment [of EU-Israel relations], an elephant in this room: the Occupation.”[11] One could add to this Israel’s settlement project, which will continue to impede bilateral relations, because it is not recognised by the outside world yet is integrated into the country’s socio-economic and political fabric.

EU actions seem to point Israel towards sustaining its practices in the OPT

Despite such warnings, the EU has proven reluctant to impose significant costs on Israel for its actions that undermine the prospects for a two-state solution, or to spell out the implications of perpetual occupation and unequal Palestinian rights for Israel’s relations with European countries. If anything, EU actions seem to point Israel towards sustaining its practices in the OPT. Furthermore, some officials from the EU and its member states have attempted to delay the implementation of legally necessary differentiation measures, in case this upsets relations with Israel or makes the task of relaunching the MEPP more difficult – even at the risk of sacrificing the EU’s internal legal integrity.

Tough love for Israel

By refusing to acknowledge that the true intent and consequences of Israeli actions is the unlawful acquisition of Palestinian territory, the EU is misdiagnosing and mistreating the roots of the diplomatic impasse. It also risks sending the wrong message to Israeli policymakers – namely, that killing off the prospects for Palestinian statehood and a two-state solution will have few, if any, repercussions in Israel’s relations with the EU.

Without an end to the occupation, the EU should look for ways to make Israel face the costs and consequences of its drift towards a one-state reality and its violations of international law. The EU should begin to state the legal and political effects of the unlawfully prolonged occupation for Israel, along with the implications of an emerging one-state reality for EU-Israel relations. This should not be about discarding the two-state solution, but rather about acknowledging that an immediate course correction is required to avoid cementing a one-state reality.

A starting point could be to reflect on the comments of former US ambassador to Israel Daniel Shapiro, who admitted:

“if Israel moves toward one of the scenarios in which Palestinians continue to lack the self-determination they legitimately seek […] it will affect our relationship at the level of what we call our common values”.[12]

The EU should be equally clear that the entrenchment of a one-state reality with unequal rights in the interim will necessitate changes to the EU’s relations with Israel, including in its 1995 Association Agreement.

More fundamentally, the EU should acknowledge that Israel’s illegal use of force to prolong its occupation and acquire Palestinian territory creates a legal obligation for third parties to intervene under international law on state responsibility. Recent work by ECFR, as well as UN special rapporteur Michael Lynk and eminent scholars of international law such as Marco Sassòli, can provide some initial policy guidance focusing on third-party responses to Israeli violations of jus ad bellum (the rules on inter-state use of force) – including the consequences of its de jure and de facto annexation of Palestinian territory and entrenchment of discriminatory practices against Palestinians in favour of its settler population.[13]

However, the EU should also explore the possibility of commissioning its own study on the legality of Israel’s continued presence in the OPT and its consequences for the EU’s third-party responsibilities.

Auditing the full spectrum of EU-Israel relations

The answer to Israeli efforts to erase the territorial basis for a two-state solution and entrench its settlement project can be found, at least in part, in the furtherance of a foreign policy based on international law and predicated on support for differentiation measures, international accountability mechanisms, and international norms. Through these differentiation measures, the EU has at times successfully pushed back on Israeli efforts to erase the 1967 Green Line, and has compelled the Israeli authorities to alter their behaviour by repeatedly excluding the settlements from their bilateral agreements.

Previous ECFR reports have gone into considerable detail on how this process can be expanded and deepened. Mogherini can play an important part in supporting a comprehensive technical review by the EEAS and the European Commission of EU-Israel dealings to identify and rectify remaining deficiencies and loopholes that give effect to Israel’s unlawful exercise of sovereign authority in the OPT.

It is legally necessary for the EU to proceed with such corrections. Indeed, many such deficiencies have already been identified and are in the process of being corrected, such as those in areas relating to EU cooperation programmes involving Israel, or imports of animal-based and other organic products. This not only ensures that the EU’s relations with Israel do not undermine its objective of a two-state solution, but also aids the full and effective implementation of EU law, in accordance with EU positions and commitments.

A change to the Israeli postcode system has allowed exports from the settlements to once again benefit from preferential tariffs under the EU-Israel Free Trade Agreement, in a worrying sign of the inadequacy of the 2005 arrangement on this issue.[14] If Israel is unwilling to assist EU customs authorities in correctly enforcing the agreement, the EU should shift this burden onto Israeli exporters.

It is also worth bearing in mind that EU institutional relations with Israel are replicated to a large extent at the level of EU member states. A cursory search through the UN’s Treaties Database (which provides only a partial snapshot) shows that there are at least 350 bilateral agreements between Israel and member states. These deals, 31 of which were concluded in the last ten years, relate to bilateral cooperation on social security, labour, tourism, investment, and research and development.[15]

Despite considerable progress in ensuring that settlement entities and activities are effectively excluded from the EU’s relations with Israel, member states remain behind the curve in their bilateral relationships with Israel. This holds true even for states that are relatively supportive of EU differentiation measures. For instance, two years after the European Commission published guidelines on the correct labelling of settlement exports, many member states – including those who called for such guidance – remain unable or unwilling to implement the guidelines at the national level.

On top of this, a large number of European businesses and investors continue to maintain financial relations with entities linked to Israeli settlements. Importantly, 18 EU member states have published business advisories warning of the legal, reputational, and financial risk of such activities; and previous French and Dutch governments have actively discouraged companies from engaging in business dealings with Israeli settlement-related projects in the OPT. But to implement these advisories, states need to provide their regulatory agencies with implementation rules for specific areas of domestic legislation, and to inform businesses of the consequences of operations related to the settlements under domestic law.

In this context, EU member states should support the upcoming UN Human Rights Council database of unlawful business activity related to settlements as a mechanism for alerting “such businesses to the consequences of activities in such a business environment, and [for providing] guidance on the measures they must adopt to comply with their responsibility to respect human rights”. The database would also “fortify the role of home-states in regulating the transnational activities of their corporate nationals through concrete domestic regulatory measures.”[16]

Supporting Palestinian reunification and re-democratisation

Europe has an important role to play in pushing Palestinian political reunification and relegitimisation, and in countering the consolidation of the PA’s authoritarian practices – all of which are essential in advancing a viable peace agreement with Israel, ensuring continued long-term Palestinian stability, and restoring Palestine’s political plurality.

As the largest donor to Abbas’s PA and a member of the Quartet, the EU should proactively engage with the Hamas-Fatah reconciliation initiative with a view to rehabilitating Gaza and stabilising the Palestinian political scene. Given that there is little hope that the two-state solution will be imminently implemented or Israel’s occupation ended, Palestinian reunification and the rehabilitation of Gaza are areas in which a degree of meaningful improvement can – and must – be achieved.[17]

The following EU policy options are well known to diplomats in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, but need greater political support from Brussels and member state capitals:

- pressing Abbas to rescind his punitive measures against Gaza’s electricity and healthcare system, which have increased humanitarian suffering;

- expressing a willingness to continue funding a new Palestinian government of national unity (even one that includes members of Hamas), so long as it holds to the PLO platform and remains committed to non-violence;

- clarifying the current no-contact policy on Hamas to allow for political engagement with moderate figures within the movement, and to enable European humanitarian organisations to operate more effectively in Gaza;

- calling for Palestinian elections and a revival of Palestinian representation mechanisms such as the Palestinian Legislative Council and the Palestinian National Council, to help smooth the post-Abbas leadership transition and inject new life into the Palestinian liberation strategy;

- warning the PA against its growing authoritarianism, including by pressing for its 2017 decree on electronic communications to be brought in line with the PA’s international legal obligations;[18]

- defending the political space for Palestinian civil society mobilisation from Israeli and PA attacks – including by providing increased legal support, and facilitating visits to EU capitals; and

- continuing to fund non-governmental organisations in Israel-Palestine that promote respect for international humanitarian and human rights law, as well as non-violent strategies to challenge Israel’s occupation and promote Palestinian sovereignty and rights.

Keeping the API alive

The EU has only a limited ability to reduce the API’s erosion through the gradual normalisation of Israeli-Gulf Arab relations. But if Gulf Arab states remain committed to increased cooperation with Israel, the EU should work with Arab, Palestinian, and US partners to explore how these growing ties might be leveraged to advance the cause of Palestinian sovereignty.

This could include discussions with the Palestinians and Gulf Arab states on what could be offered, short of normalisation, in exchange for concrete and irreversible Israeli actions to advance Palestinian sovereignty. The incentives that Arab states could provide Israel are relatively well explored. They include the offer of direct telecommunications links, overflight rights for Israeli aircraft, and increased economic and security cooperation – all of which may form part of the Trump administration’s regional peace plan.[19]

However, there is a danger that in return Israel would be asked to take relatively meaningless steps, such as promising to rein in construction outside of undefined settlement “blocks” or declaring renewed support for a two-state solution even as it continues to entrench its annexation of the OPT. Instead, any consequential move towards normalisation by Gulf Arab states should be reciprocated in kind by Israel. This could include a mixture of: allowing increased Palestinian economic access to Area C and the Gaza Marine gas field; lifting restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza; revising the Paris Protocol; freezing all settlement activity; ending demolitions of Palestinian property; and allowing Palestinian institutions in East Jerusalem to be reopened and Palestinian elections held there.

Preserving the normative and physical space for a two-state solution

Any future peace push will be more successful if the EU holds fast to the core principles of international law that have long underpinned the two-state model and the international rules-based system. While the details of a final status agreement between Israelis and Palestinians must be negotiated between the two sides, policymakers have the advantage of already knowing the parameters of a future two-state solution. These parameters have been known since at least December 2000, when Bill Clinton elaborated them based on his mediation of unsuccessful peace talks that year, and since the 2003 Geneva Initiative.

The EU and its members have also been consistent in their view of the parameters of a final deal, repeatedly laid out since the December 2009 FAC Conclusions.[20] To quote France’s ambassador to the UN:

While the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is now the oldest of the conflicts that are ripping the Middle East apart, it is also the only one whose solution is known and widely shared within the international community. Despite the constant deterioration of the situation on the ground, the parameters of a future agreement have not changed: two States living in peace and security with contiguous, secure and recognized borders drawn on the basis of the 1967 demarcation lines and mutually agreed land swaps; with Jerusalem as the capital of both States; and with an agreed, realistic, just and equitable solution for Palestinian refugees.

At a time of US policy backsliding, it is vital to maintain a willingness and ability to defend internationally endorsed parameters for resolving the conflict through a two-state solution. Mogherini underscored this point in August 2017, stating that current dynamics mean “sometimes being stubborn and [keeping] the right parameters in place when doubts and question marks arise from time to time”.[21]

At a minimum, this should translate into the rejection of any concession that could compromise Palestinian negotiating positions or international law, such as the legitimisation of Israel’s ill-defined settlement blocks.

Outside of policy discussions, though, the EU has not done enough to realise the two-state vision on the ground. Israel’s unwillingness to end the occupation should not stop the EU and its member states from promoting and translating their two-state parameters into concrete measures, where possible. Methods for doing so are explored below.

Formalising EU member state recognition of the 1967 border

EU member states should formally recognise the State of Palestine in the West Bank and Gaza based on the 1967 border. Alongside this, they should reaffirm their recognition of Israel within the 1967 Green Line, a position that has already been established through EU and member state trade practices and non-recognition of Israeli sovereignty in the OPT, as well as through many Israeli administrative and legislative practices, which differentiate between Israel and the West Bank.

Given the rapid dissipation of the two-state solution, the argument that it would be premature to recognise the State of Palestine no longer holds. Moreover, recognition of the 1967 border need not prejudice the outcome of future negotiations, which could result in changes to these borders through measures such as land swaps. This would also be in line with international humanitarian law, which precludes the acquisition of territory through the use of force and protects the occupied sovereign state from making territorial concessions “under the gun”.

Formalising the 1967 border would have the added benefit of countering domestic and international efforts by the Israeli government and its supporters to conflate Israel with Israeli settlements, erase the 1967 border, and cast doubt on the legal status of Area C of the West Bank. Such a clarification or reaffirmation would also provide an important boost to differentiation efforts by third states and private actors.

Recognising Jerusalem as the capital of two states

The international community has been united in its view that the status of Jerusalem should be negotiated as part of a final status agreement based on UN Resolution 181 (1947). For more than 70 years, third states have upheld their non-recognition of either side’s sovereignty in the city. As a result, third states currently locate their Israeli embassies in Tel Aviv rather than Jerusalem, despite Israel’s claims to the city as its undivided capital.

However, this international consensus has deteriorated in the last year. In April 2017, Russia issued an ambiguously worded statement that seemed to recognise West Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.[22] This was followed by Trump’s official recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Over time, such steps risk being matched by other states aligned with Israel and the US, including some in Europe. Indeed, only a few hours after the US announcement, the Czech Republic declared that it recognised West Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

Rather than accept the gradual deterioration of international positions on Jerusalem and the steady erosion of EU unity, like-minded EU member states should take the initiative by exploring how they can give practical effect to their position that Jerusalem should be the capital of two states. One possible course of action would be to build on recent Russian and Czech announcements by simultaneously recognising West Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and East Jerusalem as Palestine’s capital (albeit one that remains under occupation for now). EU member states could also announce that their embassies to Israel will not be moved to West Jerusalem so long as Israel denies the PLO political representation in East Jerusalem.

In parallel, the EU should focus on preserving Palestinian national identity in East Jerusalem. For example, the EU should continue to push for the return of PLO institutions to East Jerusalem and to help safeguard Palestinian national identity and cultural heritage. As a more immediate practical step, the EU could also explore ways to provide financial support to Palestinian schools and other public, as well as non-governmental, institutions in East Jerusalem. Palestinian schools are particularly vulnerable, given that their receipt of Israeli state funds is now conditioned on the adoption of textbooks approved by the Israeli government.[23]

Defending Palestine’s territorial contiguity

The continued fragmentation of Palestinian territory through concerted Israeli actions continues to severely undermine efforts to establish a viable and contiguous Palestinian state based on the Green Line. At the same time, political divisions and Israeli restrictions risk separating Gaza from the rest of Palestinian territory and depriving Palestinians of any new strategy to effectively challenge Israel’s occupation.

The current Hamas-Fatah reconciliation process provides an important window for beginning to end Palestinian political divisions and to remove Israeli restrictions on access and movement in Gaza. However, the EU should also promote efforts to increase Gaza-West Bank travel and trade by calling for the immediate establishment of a land corridor that facilitates free movement between the two areas. Helping develop Palestinian energy exports from the Gaza Marine gas field and boosting the Gaza Strip’s economy could also reinforce these economic links.

Alongside this, the EU should step up its efforts to preserve a Palestinian socio-economic presence, and protect vulnerable Palestinians in East Jerusalem, Area C (including the Hebron Hills), and Jerusalem’s E1 Area from Israeli actions that are illegal under international law. This could include strengthening EU financial and political support for legal assistance to Palestinian residents facing confiscations, demolitions, and eviction orders, in line with recommendations made in the 2016 EU heads of mission report on Jerusalem.

In addition, Brussels should throw its political weight behind ongoing EU efforts to provide humanitarian aid to vulnerable Palestinian communities in Area C (undertaken by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, the EU delegation to East Jerusalem, and some member states), and to advance their plans for urban and regional development.[24]

Is there a path to Palestinian sovereignty under occupation?

Israeli politics and public opinion currently show no sign of ending the occupation or allowing for the emergence of a fully independent and contiguous Palestinian state. However, this has not prevented Palestine from acquiring the characteristics of statehood and sovereignty.

Many European countries have acknowledged the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination since June 1980, when the European Economic Community issued its Venice Declaration. Moreover, 136 countries have explicitly recognised the State of Palestine, while many others have done so implicitly. The UN General Assembly recognised Palestine as a “non-member state” in November 2012. The International Court of Justice acknowledged Palestinian statehood in its 2004 advisory opinion on the legal consequences of Israel’s construction of a wall in the OPT.[25] The International Criminal Court (ICC) has made a similar determination by: affirming the occupied status of the Gaza Strip in the case of the Mavi Marmara aid ship; accepting Palestine’s accession to the Rome Statute of the ICC; and initiating a preliminary investigation into the “situation of Palestine” through the examination of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Palestinian territory.

Alongside this, the State of Palestine can claim to have a recognised government led by Abbas, as well as a police force and functioning institutions. Just as importantly, it can argue that international law and customary practice has largely settled the question of its borders according to the Green Line.

Sovereignty-building strategies

Although Israel’s military occupation denies Palestine the ability to independently control its territory, the fact that this territory is occupied and hence under de jure Palestinian sovereignty means that EU and its member states should treat it as a legitimate sovereign, even if doing so falls short of a formal recognition of its statehood. In a similar fashion, Namibia became a sovereign state while still under South African occupation.[26]

The EU should incorporate this consideration into its foreign relations, even in a situation in which the majority of member states have not recognised the State of Palestine. It can do this by exploring the ways in which aid can be redirected away from its current narrow focus on technocratic governance and security and towards the promotion of Palestinian sovereignty-building strategies. Crucially, such strategies should aim to promote Palestinian sovereignty not just in international forums but also on the ground in the OPT. As former Palestinian prime minister Salam Fayyad wrote: “the one battle for Palestinian statehood that […] will matter most [is…] the comprehensive and relentless campaign and dedication to project the reality of Palestinian statehood on the ground despite the occupations, and as a means of ending it”.[27]

To be clear, such initiatives are not a substitute for ending Israel’s occupation. But they can be paired with continued EU efforts to disincentivise Israel’s unlawful acquisition of Palestinian territory. These efforts could take some of the forms explored below.

National sovereignty

Even if attempts to build Palestinian institutions have been broadly successful, there is still much to do in making these institutions – and their ministers – more responsive and accountable to the needs of citizens. Strong local governance and inclusive policy debates are arguably an integral attribute of sovereignty, providing space for popular participation in the decision-making process and the promotion of civil leadership. This bottom-up process in turn helps legitimise governance decisions.

In the case of Palestine, such debates are also important in promoting a national conversation on: the future of Palestinian state-building and the PA’s function under prolonged occupation; the merits and means of revising the Paris Protocol; and the consequences of shifting to a one-state paradigm, or tearing up the Oslo Accords. In addition, the concept of “participatory democracy” can help relegitimise the Palestinian decision-making process by enhancing national ownership of Palestinian strategy – at a moment when Palestinian legislative bodies are frozen and there is little likelihood of imminent elections.

In identifying areas in which it can support Palestine’s transition from state-building to sovereignty-building, the EU should align its approach with Palestinian National Development Plans, and the recently published UN Development Assistance Framework for the State of Palestine.[28] The EU can also support Palestinian civil society initiatives to develop and promote national policies and service delivery in healthcare, taxation, education, gender equality, and urban planning – with a special focus on vulnerable areas. This could potentially include funding Palestinian think-tanks that deal with domestic public policy issues.

Alongside this, the EU and its member states can develop practical ways of supporting and strengthening the capacity of the Palestinian diplomatic and civil service by:

- exploring how to strengthen Palestinian diplomatic capacity and expertise, including by upgrading PLO missions and consular services in member state capitals, as well as by providing scholarships for young Palestinian diplomats to study in Europe;

- supporting Palestine’s domestic legislative and administrative implementation measures and reporting, in line with Palestine’s obligations under a host of international treaties that it has ratified since 2011, such as the seven core UN human rights treaties, among them: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the optional protocol on the convention on the rights of the child; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization instruments; the Geneva Conventions; and the Rome Statute of the ICC; and

- supporting Palestinian efforts to, as the UN Development Programme puts it, “effectively monitor, advocate, and seek legal recourse for violations by the occupying power”, including through international accountability mechanisms such as the UN Human Rights Council and the ICC.[29]

Economic sovereignty

Economic measures should also be at the core of the EU’s support for Palestinian sovereignty-building strategies. As Nisreen Musleh and Sam Bahour recently noted, “Palestine’s economic survival, and maybe political survival as well, depends on finding livelihoods for many more Palestinians, and at an unprecedented rate.”[30] This holds especially true for Gaza, which suffers from 58 percent youth unemployment despite having considerable economic potential.

Efforts to promote Palestinian economic sovereignty can help prevent the deterioration of the PA’s effectiveness and create a more vibrant Palestinian economy. They can also support enhanced Palestinian fiscal and economic independence, thereby relieving the EU’s burden of financial assistance to Palestine and transforming Palestinians from aid recipients into citizens of a sovereign nation.

However, the development of Palestine’s economy (which would likely form a key part of a future US regional peace deal) should not be treated as a substitute for a final peace agreement with Israel but rather as an important element in the political equation. As ECFR senior policy fellow Mattia Toaldo noted in June 2013, such measures can be a useful means of testing Israeli willingness to allow the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.[31] Further steps along these lines could include:

- advancing European Commissioner Johannes Hahn’s call for “a review of the provisions of the 1994 Paris Protocol on taxes, customs clearance revenues, trade and labour movement – and [… looking] at the implementation of the current provisions”;

- supporting enhanced Palestinian tax collection in the West Bank, including making such demands of private individuals and businesses located in Israeli settlements;

- promoting Palestine’s sovereignty and control over its natural resources, including by pushing Israel to allow Palestinian businesses greater economic access to Gaza and Area C;

- helping elaborate a “Marshall Plan for Gaza” that would include support for the PA’s development of the Gaza Marine gas field; and

- backing the development of the Palestinian agriculture and tourism sectors, including through support for grassroots business initiatives that help promote Palestinian sovereignty.[32]

Surmounting internal EU divisions

The staying power of any new policy will depend on the EU’s ability to operate as a unified and coherent political actor. However, the EU’s current inability to improve its internal consensus – and the paralysis this has produced, particularly in relation to Israeli actions that threaten the future of the two-state solution – has fed growing frustrations among the majority of member states.

While the need to acquire the consent of 28 governments has progressively reduced the scope for EU action, past achievements have shown that EU policy can be advanced through initiatives driven by member states even where unanimous consent no longer exists. Some countries, such as Germany, remain committed to working through the EU to defend the organisation’s legal integrity and positions on international law in its dealings with Israel, and to making progress in areas in which there is an EU-wide consensus.

Others have chosen to act by themselves, outside of the EU’s structures or consensus. For instance, in October 2014, Sweden became the first EU member to recognise the State of Palestine. France began its own peace initiative in 2016. Although they were effective to different degrees, both efforts have been privately criticised by some EU officials for diminishing the potential power of the EU collective or undermining EU institutions.

Nonetheless, like-minded member states have sometimes come together to trigger EU action. In October 2017, Belgium mobilised a handful of EU countries (likely including France, Spain, Sweden, Luxembourg, Italy, Ireland, and Denmark) to demarche Israel for its confiscation of EU-funded equipment in Jubbet Adh-Dhib and Abu Nuwar. These countries are reportedly preparing to present Israel with a bill for €31,252 should it fail to return the confiscated items.[33] In April 2015, 16 member states called on the European Commission to issue guidelines on labelling products from Israeli settlements – which it eventually did the following November, receiving intense criticism from the Israeli government and its supporters.[34] In June 2013, member states came together at the EU working level in Brussels to develop common messaging on business activity in the settlements.[35]

The pending departure from the EU of the UK (which under prime minister Theresa May has blocked EU statements and actions against Israeli settlement policies), together with the extension of emerging Franco-German cooperation on the MEPP, could bolster such initiatives. The resulting momentum could not only produce a more distinct and bold European voice but also renew European action by an ad hoc grouping of like-minded states – as occurred in relation to compensation in Area C.

However, the key to progress is empowering Mogherini, the European Commission, and the EEAS in their separate capacities, which could translate energy generated within individual member states into an EU initiative to implement existing law and policy positions. Just as importantly, like-minded member states could provide political backing to Mogherini and the European Commission when they follow through on relevant requests from member states. As one EEAS diplomat remarked following the commission’s publication of settlement-labelling guidelines: “member states let us crash. If member states don’t back us, why should we be fooled again?”[36]

Biography

Hugh Lovatt is a Policy Fellow with ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme. He has worked extensively to advance the concept of “EU differentiation” between Israel and its settlements, which was enshrined in UN Security Council Resolution 2334 (December 2016). His most recent publication is “Rethinking Oslo: How Europe can promote peace in Israel-Palestine” (July 2017).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Vassilis Ntousas and the Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), without whose support this publication would not have been possible. I am indebted to ECFR colleagues, in particular editor Chris Raggett for his patience and diligence. I also owe special gratitude to the countless individuals who have offered thoughts and improvements. As ever, any faults or omissions are solely my own.

*The V4/ Visegrád 4, are the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia

Download the full report here, pdf file