Why Israelis insult foreign critics

Susiya villagers present Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman with a gift

Why Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman’s Older Children Didn’t Come With Them to Israel

During book launch in West Bank for book of essays marking 50 years of occupation, U.S. Jewish literary couple talk about that uncomfortable subject

By Judy Maltz, Haaretz premium

All photos by Shiraz Grinbaum

June 24, 2017

Where do they get the chutzpah to lecture Israelis on the evils of occupation?

Since the release of their brand new anthology of essays dedicated to this fraught subject, Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman, America’s literary power couple, tackle this question all the time. Not that they didn’t see it coming.

“I expected it, but I still think it’s sad,” Chabon, the bestselling and Pulitzer-Prize-winning Jewish author, told Haaretz. “It comes from people who don’t want the occupation to be known about or talked about. So they resort to name-calling – they call us self-hating Jews, anti-Semites, traitors, outsiders, foreigners, unsophisticated, stupid, naïve, whatever. But as I see it, they’re just lazy and don’t have anything new to offer to the discussion.”

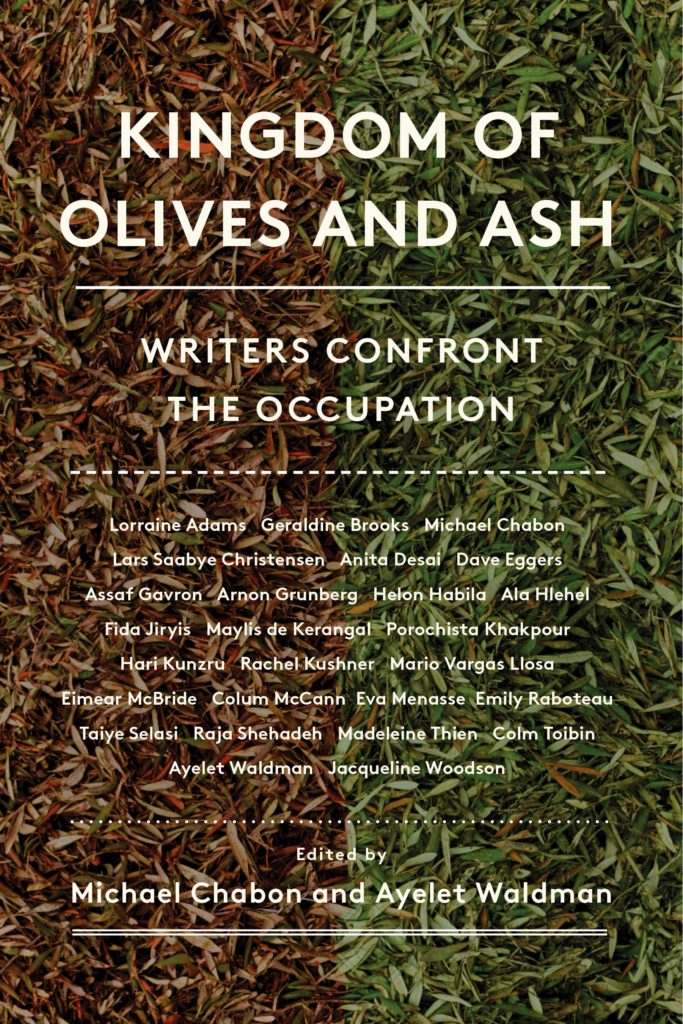

Chabon and Waldman are in Israel this week attending a series of book-launching events for the Hebrew-language version of “Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation.” The anthology, which they co-edited, contains essays by 26 renowned writers from 14 countries, among them Mario Vargas Llosa, Dave Eggers, Rachel Kushner and Colm Toibin.

The project was launched in collaboration with Breaking the Silence, an organization of former Israeli combat soldiers dedicated to fighting the occupation, to mark the 50th anniversary of Israel’s conquest of the West Bank during the Six Day War.

On Wednesday, a group of prominent Israeli writers joined Chabon and Waldman for a tree-planting ceremony in the West Bank village of Sussia that followed the book launch. Located in the south Hebron hills, Sussia belongs to an area of the West Bank under full Israeli military control. The choice of this location for the literary event was not random: Several essays in “Kingdom of Olives and Ash” were inspired by visits to this tiny village of 350 residents, which has become a cause célèbre in recent years because of Israel’s repeated attempts to demolish it.

Nasser Nawaja, the unofficial spokesman of Sussia, briefed the visitors on the traumatic history of the village. In 1986, he related, the residents were evicted from their original location after Israeli authorities took it over for an archeological dig. The evicted Palestinian families moved into caves and shacks on agricultural lands they owned nearby. Since then, their homes have been demolished several times and all their attempts to obtain permits to build legally on their land have failed.

Ayelet Waldman reads from the book.

“We don’t believe in obtaining justice from the Israeli court system,” Nawaja told the writers and activists gathered in a tent-like structure on the dusty hilltop. “But we do believe that through the pens of writers and pressure from around the world, we can fight this.”

Why Sussia?

Sussia is one of a dozen villages in the south Hebron hills whose residents live under the constant threat of eviction because the area was declared a firing zone by the Israeli army. “We believe that if we succeed in preserving and defending Sussia, we can defend these other villages as well,” said Nawaja, “and then all of the other Palestinians villages around here that Israel controls.”

The international group of writers who contributed to the anthology visited the occupied territories, either in groups or on their own, on trips organized by Breaking the Silence over the past few years. In order to give Israeli writers a similar opportunity to bear witness, said Chabon, it was decided to hold this particular book launch in Sussia.

“For me, it’s ultimately about seeing for yourself, and I think that as soon as you do see for yourself, a lot of the doubt and confusion you might have around the issue of the occupation disappears,” said the author, among other books, of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union and Moonglow.

“The conflict is not simple. The conflict is confusing, I think there are multiple sides, and that is legitimate. You can honestly and truly say that you don’t understand and that you can see it this way or that way. But when you see the occupation itself close up, there’s no doubt and no uncertainty of just how wrong it is.”

For Israeli author Dorit Rabinyan, this was a first trip of its kind to the West Bank. “I’ve snuck in here and there but never on an organized trip like this,” confessed Rabinyan, whose novel “All the Rivers” was blacklisted by the Education Ministry because its subject was a Jewish-Arab love story.

She said she hoped to promote two causes close to her heart by participating in this event. “There is, of course, the cause of literature, and some of the writers who have contributed to this anthology I really love, “ said Rabinyan, “and the other important cause is taking off the blindfold and opening our eyes to what is happening around us here because we Israelis have a tendency to self-anaesthetize and look the other way.”

Dorit Rabinyan at the tree-planting ceremony.

It was also a first trip to this Palestinian village for Noa Yedlin, winner of the prestigious Sapir Prize for literature. “To say no to an invitation to come here, I felt that would be immoral,” she said. “That would be the equivalent of saying yes to the occupation and everything else bad happening in this country.”

For her, it was also a way to express solidarity with Breaking the Silence, an organization that has been repeatedly attacked and targeted by Israel’s right-wing government. “They say that Breaking the Silence gives Israel a bad name around the world,” Yedlin said. “I say the contrary. The fact that there are voices like this in Israel who speak freely and that there are people listening to them – that says something very good about the country. So taking a few hours out of my day to come here and plant a tree – as I see it, that’s the minimum I can do.”

Answering the common critiques

In a recent review of “Kingdom of Olive and Ash,” Liel Leibovitz of Tablet Magazine summed up some of the common critiques of the book. “With the book’s galley came the gripes, arriving via email and social media from like-minded friends,” he wrote. “Do we really need another meditation on the conflict? And don’t we deserve better than a host of authors who, by their own account, knew little or nothing about our ordeals before landing at Ben-Gurion airport with a tourist visa and a vengeance? And would it have killed the celebrated authors to include, among the sea of Palestinian suffering, the view from Israel as well?”

Yedlin challenges the detractors. “So what’s the alternative?” she asks. “That people don’t come here? That they don’t get exposed to what’s going on? That they don’t write about it? We should be happy that they want to come.”

And besides that, she asks, who’s to say that an Israeli from Tel Aviv or Ra’anana (“present company included,” she says) has a better sense of how the occupation works than a visitor parachuting in from Norway, America or anywhere else in the world? “Do I know more about what’s going on here than Michael Chabon?” she asks. “I don’t know. I’m not at all sure that I do.”

Jewish American social activists in Susiya.

Also participating in the writers’ delegation were David Shulman (a renowned Israeli anthropologist), Avrum Burg (a former speaker of the Knesset and chairman of the Jewish Agency) Julia Fermentto, Tzipora Dolan, Nissim Calderon and Iris Leal.

Chabon and Waldman brought only their two youngest children with them on this trip because the two oldest refused to come. That is something that should concern not only their parents who begged them to come, said Waldman, but all Israelis.

“So many Israelis misunderstand the American Jewish community because they think the American Jewish community is AIPAC and Sheldon Adelson,” said Waldman, author of the novel “Love and Treasure” and the recent memoir “A Really Good Day.”

“They don’t understand that 70 percent of American Jews voted for Hillary Clinton and we are very, very progressive people,” she said. “Unlike our generation and our parents’ generation, our kids are not content to live with the existential hypocrisy that you can be progressive on everything until it comes to Israel. They refuse to check their morals and values at the door.”

Had they offered them a trip to Japan, she said, their oldest children would have gladly tagged along. But under no circumstances were they willing to travel to Israel. “They don’t want to think or hear about the place,” Waldman said. “And as I see it, they’re a lost cause.”

Both Waldman and Chabon are convinced that only pressure from the United States, in particular the American Jewish community, can help end the occupation. “I think there’s ample reason to hope that the occupation will end,” said Chabon. “The question is how bloody and violent or how relatively peaceful the process will be.”

Dorit Rabinyan, crouching in green shirt, and Michael Chabon in back centre, with other activists and writers at the tree-planting ceremony.