The capture of Israel by religious messianics

Palestinians surrender to the superior military power of Israeli soldiers in June 1967 in the occupied territory of the West Bank. Photo by Pierre Guillaud/AFP

Fifty Years of Occupation

A Forum

By Joel Beinin , Noura Erakat , Zachary Lockman , Maha Nassar, Ilana Feldman

June 05, 2017

June 5, 2017 is the fiftieth anniversary of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, which culminated in the Israeli military occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip and the Golan Heights, among other transformations of regional politics. The post-1967 occupation and its consequences continue to structure the mainstream conversation about resolving the conflict between Israel the Palestinians, and those between Israel and other Arab states, even as scholarship increasingly poses the occupation as part of a longer-term and more multi-faceted question of Palestine. We asked several specialists to reflect on the past, present and future of the question of Palestine at this historical juncture.

“Beautiful Israel” and the 1967 War

Joel Beinin

The 1967 Arab-Israeli war unleashed forces that reshaped Israeli politics and society. But much about the war is rooted in the military tactics, governance practices and political culture of “beautiful Israel,” as liberal Ashkenazi Zionists often nostalgically refer to the pre-1967 state. This is true of the decision to launch the war. It is true of the impulse for territorial expansion, manifested by the annexation of a vastly expanded East Jerusalem on June 28, 1967 and the establishment of the first civilian Jewish settlements in the Golan Heights and the West Bank in July and September. And it is true of the imposition, following the six days of fighting, of military rule on the Palestinians of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

The countdown to the 1967 war began with sharpening military clashes between Israel and Syria. In a posthumously published interview with journalist Rami Tal, Moshe Dayan, former Israel Defence Forces chief of staff and minister of defence in June 1967, explained that before the war IDF methods on the Syrian border consisted of

snatching bits of territory and holding on to it until the enemy despairs and gives it to us.

…After all, I know how at least 80 percent of the clashes there started. In my opinion, more than 80 percent, but let’s talk about 80 percent. It went this way: We would send a tractor to plough some area where it wasn’t possible to do anything, in the demilitarized area, and knew in advance that the Syrians would start to shoot. If they didn’t shoot, we would tell the tractor to advance farther, until in the end the Syrians would get annoyed and shoot. And then we would use artillery and later the air force also, and that’s how it was…. We thought that we could change the lines of the ceasefire accords by military actions that were less than war.

Menachem Begin’s Herut (Freedom) Party, which emerged from a pre-state terrorist militia, the Etzel (commonly known as the Irgun in English), never accepted the 1949 armistice lines (the Green Line) as Israel’s legitimate border. The movement’s territorial aspirations were expressed in the refrain of a poem by the leading ideologue of the Zionist right, Vladimir Jabotinsky:

“Two Banks has the Jordan / This one is ours, and that one as well.”

Herut was marginal to Israeli politics until the 1967 war. On the eve of the war Begin joined the governing coalition as minister without portfolio. A decade later he became prime minister.

An influential kibbutz-based Labour Zionist movement—Le-Ahdut ha-‘Avodah (Unity of Labour)—which, like Herut, had opposed the partition of British Mandate Palestine into an Arab and a Jewish state, also harboured irredentist sentiments. Its members dominated the officer corps of the pre-state Labour Zionist militias, the Palmach and Haganah. From 1954 on Le-Ahdut ha-‘Avodah was an independent party led by Yisrael Galili, former chief of staff of the Haganah, and Yigal Allon, a founder of the Palmach. Both were ministers in the government that launched the 1967 war.

In June 1966, the theoretical guru Yitzhak Tabenkin of Le-Ahdut ha-‘Avodah’s , declared, “Anywhere war will allow, we shall go to restore the country’s integrity” (Tom Segev, 1967: Israel, the War and the Year That Transformed the Middle East, p. 180). In July 1967 Tabenkin became one of the founders of the Greater Israel Movement, which advocated annexation and settlement of the territories occupied the preceding month.

They didn’t even try to hide their greed for that land

Members of Le-Ahdut ha-‘Avodah-affiliated kibbutzim convinced Dayan to conquer the Golan Heights on the fourth day of the 1967 war, a decision he later regarded as his worst political mistake, as after Israel destroyed its air force on the first day of the war, Syria no longer posed a threat. As Dayan recalled in the same conversation with Tal,

The kibbutzim there saw land [on the Golan Heights] that was good for agriculture…. And you must remember, this was a time in which agricultural land was considered the most important and valuable thing…. The delegation that came to persuade [Prime Minister Levi] Eshkol to take the heights…were thinking about the heights’ land. Listen, I’m a farmer…. I saw them, and I spoke to them. They didn’t even try to hide their greed for that land.

Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek commissioned Naomi Shemer to write “Jerusalem of Gold.” The words express Jewish longing for the Old City of Jerusalem, then part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan:

How the cisterns have dried

The marketplace is empty

And no one frequents the Temple Mount

In the Old City.

And in the caves in the mountain

Winds are howling

And no one descends to the Dead Sea by way of Jericho.

“No one,” of course, means “no Jew,” since thousands of Palestinian Arabs did these things daily. Such Israeli erasures of Arab presence were routine by 1967. They were facilitated by the expulsion of some 725,000 Palestinians during the 1948 war. Subsequently, military rule was imposed on almost all of Israel’s Palestinian Arab citizens until 1966. They were largely segregated in villages and impoverished neighbourhoods in half a dozen “mixed cities.” In the early 1960s the army developed contingency plans to establish military rule over the West Bank and Gaza Strip should these lands be occupied in a conflict (Neve Gordon, Israel’s Occupation, p. 10).

The war broke out on June 4, three weeks after “Jerusalem of Gold” was first performed; it became the unofficial anthem of Israel’s victory. On June 7, when Israel conquered the Old City of Jerusalem and its environs, Dayan proclaimed, “This morning, the Israel Defence Forces liberated Jerusalem. We have united Jerusalem, the divided capital of Israel. We have returned to the holiest of our holy places, never to part from it again.”

To celebrate the “reunification” of Jerusalem, Shemer added a verse to her song that ensconced its annexation as uncontestable in Israeli popular culture:

We have returned to the cisterns

To the market and to the marketplace

A ram’s horn calls out on the Temple Mount

In the Old City.

And in the caves in the mountain

Thousands of suns shine—

We will once again descend to the Dead Sea

By way of Jericho.

The most disturbing aspect of contemporary Israel for those nostalgic for pre-1967 “beautiful Israel” is the hegemony of the alliance of messianic religio-nationalism and anti-democratic national chauvinism. This phenomenon, too, has pre-1967 origins.

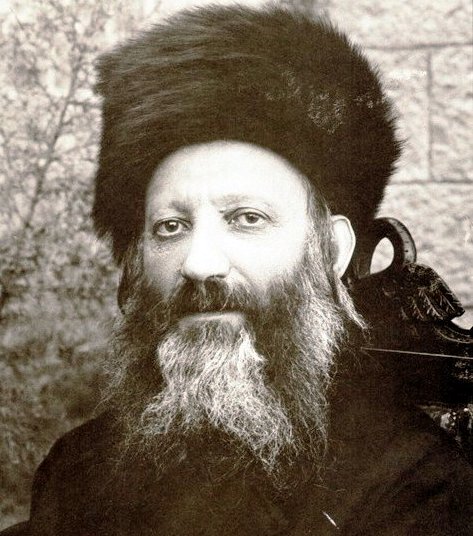

In 1924 Avraham Yitzhak Kook (1865-1935), the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine, founded the Merkaz ha-Rav yeshiva (school for higher religious studies) in Jerusalem. There he taught “practical messianism”—the doctrine that returning to Zion and establishing a Jewish state were preparatory stages leading to the Messianic Era. Kook saw secular Zionists as the “Messiah’s donkey” (a reference to Zechariah 9:9)—God’s unwitting tool for hastening the coming of the Messiah.

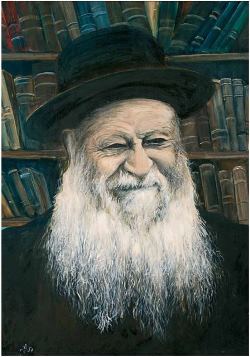

Tzvi Yehuda, L, and father Avraham Yitzhak Kook

Tzvi Yehuda Kook (1891-1982) radicalized his father’s teachings. His sermon on Israeli Independence Day, May 15, 1967, anticipated the ethos that eventually characterized post-1967 Israel.

…Nineteen years ago, on the night when news of the United Nations decision in favour of the re-establishment of the state of Israel reached us, when the people streamed into the streets to celebrate and rejoice, I could not go out and join in the jubilation. I sat alone and silent; a burden lay upon me.… I could not accept the fact that indeed ‘they have…divided My land’ (Joel 4:2)! Yes [and now after 19 years] where is our Hebron—have we forgotten her?! Where is our Shechem [Nablus], our Jericho—where?! Have we forgotten them?!

And all that lies beyond the Jordan—each and every clod of earth, every region, hill, valley, every plot of land, that is part of the Land of Israel—have we the right to give up even one grain of the Land of God?! On that night, nineteen years ago, during those hours, as I sat trembling in every limb of my body, wounded, cut, torn to pieces—I could not then rejoice.

When Israeli forces captured Jerusalem’s Old City three weeks later, Kook’s followers proclaimed these words a prophetic sign on the road to redemption. Kook and his followers regarded any withdrawal from “the eternal land of our forefathers” as religiously forbidden. They believed that settling all of the Land of Israel was the foremost of the 613 biblical commandments.

Kook’s views informed the religious wing of the Greater Israel Movement and Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful), the religio-nationalist settler movement founded in 1974, as well as settler leaders like Chanan Porat, a founder of the first West Bank settlement, Kfar Etziyon, established in September 1967 and Moshe Levinger, the principal figure of the Hebron/Kiryat Arba settlement established in 1968. Long before Kook’s views were openly articulated by cabinet ministers, as they have been since Benjamin Netanyahu returned for his second run as prime minister in 2009, they infused a new élan and direction into Israeli society, much as the kibbutz movement did before the 1967 war.

Joel Beinin is Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History and professor of Middle East history at Stanford University and a contributing editor of Middle East Report.

Familiar Ruptures and Opportunities, 1967 and 2017

By Noura Erakat, MERIP

The 1967 war was a fundamental, damning failure for the Arab world. In the course of six short days, Israel expanded its jurisdiction across the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula and the Syrian Golan Heights, as well as the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. For 19 years, Arab states had regarded Israel as a foreign colony established by the collusion of imperial powers. Amid the anti-colonial fervour that animated much of the global south at the time, these states refused to recognize Israel as a Jewish homeland. They demanded that Palestinian refugees be allowed to return and given the right to govern themselves as promised by Britain, the League of Nations Mandate system and the UN Charter. Israel’s expansion of its territorial holdings blunted the force of those demands.

Among the less frequently cited deleterious effects of the 1967 war is the way in which it reified the juridical elision of Palestinian peoplehood and the attendant right of Palestinians to self-determination. This erasure was first accomplished with the drafting of the Balfour Declaration in 1917 and then upon the incorporation of that text into the Palestine Mandate in 1922. Upon declaring its independence in 1948, Israel legally justified its right to statehood with reference to UN General Assembly Resolution 181, stipulating that Mandatory Palestine should be partitioned into an Arab and a Jewish state without discrimination as to the civil and religious rights of the minority populations. Israel denied that Palestinians had a similar right to statehood because Arabs had rejected Resolution 181.

Rather than correct this juridical erasure, UN Security Council Resolution 242, passed in an attempt to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict, consecrated it. Resolution 242 predicated the return of Arab lands upon a permanent peace between Arab states and Israel. It failed to recognize the national rights of Palestinians, referring to them as a non-descript “refugee problem.” Egypt and Jordan, seeking to regain territories lost in the 1967 fighting and believing that Israel within its pre-1967 borders was there to stay, voted for Resolution 242. This failure catalyzed the Palestinian national movement, which took the helm of the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1968 and insisted upon leading its own cause, rather than leaving it as a derivative concern of pan-Arabism.

The elision of Palestinian peoplehood remains central to the ongoing conflict as well as to Israel’s settler-colonial mechanisms of dispossession, removal and concentration of the native population. It was upon the fiction of Palestinian non-existence that Israel could construct a legal argument denying the de jure occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

It is in accordance with this same fiction that Israel denies Palestinians the right to use armed force, as a matter of law, and deems all such incidents as criminal and terroristic. And of course, it is the fiction of non-peoplehood that permits Israel to deny Palestinian self-determination as a matter of positive right. The ambition to resist these conditions, and instead to inscribe the juridical peoplehood of Palestinians among other states in the form of recognition as well as within UN resolutions and procedures, drove the PLO’s legal and diplomatic agenda for nearly two decades.

Over the course of the early 1970s, the PLO achieved recognition as the sole, legitimate representative of the Palestinian people at the Organization of the Islamic Conference, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organization of African States, as well as at the Arab League, over the protest of Jordan, which continued to lay claim to the West Bank. Having established the requisite groundwork among these regional bodies, the PLO turned its attention to the United Nations.

In 1974, it drafted General Assembly Resolution 3236, which aimed to supplant Resolution 242 as the guiding framework for establishing Middle East peace. Whereas 242 stipulated a permanent Arab peace with Israel without mutual recognition of Palestinians, 3236 reaffirmed “the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people in Palestine, including: a) the right to self-determination without external interference; [and] b) the right to national independence and sovereignty.”

UNGA Resolution 3236 was a coup as it enabled Palestinians to pursue a diplomatic strategy without having to recognize, negotiate with and reconcile with Israel. That same year, the PLO introduced and passed General Assembly Resolution 3237 recognizing the PLO as the sole, legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and earning it non-member observer status at the UN. Together, Resolutions 3236 and 3237 created an alternative framework to UNSC Resolution 242 and re-inscribed the juridical status of the Palestinian people as a matter of international law, thus demonstrating the PLO’s efficacy.

Between 1974 and 1977, the PLO participated in the preparatory conferences culminating in the adoption of the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions with the purpose of regulating irregular combat. The Protocols effectively legitimized armed force employed by non-state actors in civil wars and, more pointedly, in wars of national liberation. For the PLO, however, the primary aim underpinning participation in the Protocols talks was a further inscription of its embryonic sovereignty. These ambitions may have yielded positive outcomes for the Palestinian liberation struggle at the height of the power of the Non-Aligned Movement and the prevalence of national liberation movements worldwide, but as the relative clout of these forces began to wane, the PLO’s strategy fell out of place. The PLO’s diminishing influence, marked by its exile to Tunisia, the decline in external funding, and the rise of internal political threats from Hamas and organic leaders in from the Territories, exacerbated this condition. In the late 1980s, the narrow pursuit of juridical recognition ultimately led the PLO to embark on a strategy of capitulation and accommodation best captured by the unfavourable terms of the 1993 Oslo agreement.

By entering into the Oslo accords, the PLO’s moderate flank achieved what it had wanted the most since the early 1970s: Israel’s recognition of the juridical status of Palestinians as a people. It achieved this goal in exchange for freedom. Oslo was a reformulated draft of the autonomy framework first captured by the 1979 Camp David accords establishing peace between Egypt and Israel. Autonomy, unlike statehood, did not link sovereignty and jurisdiction to all peoples and lands. Moreover, autonomy is equally available to oppressed minorities, indicating the irrelevance of peoplehood in its governing apparatuses. Statehood, which is available only to a people, was explicitly off—and never on—the negotiating table. Unlike the Palestinian negotiators in Washington who rebuffed Israel’s efforts in that direction, the PLO in the Oslo back channel accepted Israel’s terms. It also agreed to amend its charter, relinquishing its commitment to armed struggle.

Over the following 24 years of the Oslo era, Israel, with the close co-operation of the Palestinian Authority (PA), has operationalized autonomy and transformed it into a viable arrangement. Not only has autonomy facilitated the dramatic increase of the settler population from approximately 200,000 to 600,000, but it has also retooled Palestinian police forces into a security apparatus for the settlements and their attendant infrastructure. Israel has entrenched its settler-colonial enterprise in Area C, or 60 percent of the West Bank, and is on the cusp of annexing this land as a matter of law. Notably, Israel’s settler-dominated government has revived a discourse of the non-existence of a Palestinian people evidenced by renewed calls to transfer Palestinians to Jordan as well as the 2012 Levy Committee finding that there is no occupation. Denying the juridical status of Palestinian peoplehood today would provide Israel with a (dubious) legal argument that it is annexing land that belongs to no other sovereign. On the horizon looms a reversal of the PLO’s ultimate achievement to date.

Worse, perhaps, is the fact that indefinite military occupation has severely altered the territorial, juridical, geographic and social status quo in place before the start of hostilities in early June 1967. Rather than revolt against these conditions, the Fatah-dominated PA, which has effectively subordinated the PLO, continues to pursue a statehood strategy without regard to the evolving conditions or new realities of de jure discrimination tantamount to apartheid. The PA/PLO strategy does not even remain committed to the PLO’s vision articulated in its Declaration of Independence (1988) and has, at nearly every juncture, attempted to accommodate rather than resist Israel’s domination. Not everyone has suffered equally, which helps to explain this conundrum. The unending process of negotiations has significantly enriched a Palestinian economic and political elite, which has acquired a vested interest in the new status quo.

What has become clear is that the framework of Palestinian nationalism established in the aftermath of the 1967 war is no longer sufficient to drive a liberation movement. That framework has been assaulted, and today is mutilated to the point of non-recognition. While Israel’s settler-colonial regime remains the most significant obstacle to Palestinian freedom, the first step in combating it must be the removal of a Palestinian national and economic elite that makes it viable. At the very least, Palestinians must also articulate and establish an alternative national liberation framework.

The bad news is that a robust nationalist movement does not yet exist. The most significant national body to emerge since 1993 is the Boycott National Committee (BNC), which guides the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. The BNC, however, has been resolutely clear that it is not an alternative to the PLO and that, in practice, the BDS movement is an international solidarity movement based on human rights norms and devoid of a political vision. The good news is that Palestinians are in a very familiar position.

As in the aftermath of the 1948 and 1967 wars, when Palestinians took tremendous losses and were plagued by inept leaders, they face devastating odds today. What is coming next is a more serious deterioration of conditions on the ground, signalled by bolder Israeli moves to consolidate colonial takings and a securitization of the West Bank, much like it has already achieved in Gaza, that deepens the vulnerability of Palestinian civilians.

But there is an end to this downward spiral. At that point, or in its approximation, Palestinians will likely initiate a new chapter of resistance shaped by articulations of freedom responsive to the present-day status quo. Perhaps this assessment is overly optimistic but, at the bottom of the well, there is no way to go but up. Either Palestinians meet this challenge or accept their erasure. Such surrender is even more unlikely than the scenarios conjured by unbridled optimism. The inscription of Palestinian peoplehood in the juridical corpus is insufficient to ward off erasure. A people only exist to the extent that they resist their elimination; it is the act of resistance, and not the language of law, that ensures existence. A once vibrant PLO made that clear in the aftermath of the 1967 war, and the dismal conditions today demand a similar resuscitation of intrepid vision and leadership.

Noura Erakat is a human rights attorney, assistant professor at George Mason University and co-founding editor of Jadaliyya. This essay is based on work for her forthcoming book, tentatively titled Law as Politics in the Palestinian-Israel Conflict.

Also in this series:

One Anniversary Among Many, Zachary Lockman

Resistance and Solidarity Across the Green Line, Maha Nassar

Fifty Years of Disavowal, Ilana Feldman