I can’t be antisemitic because…

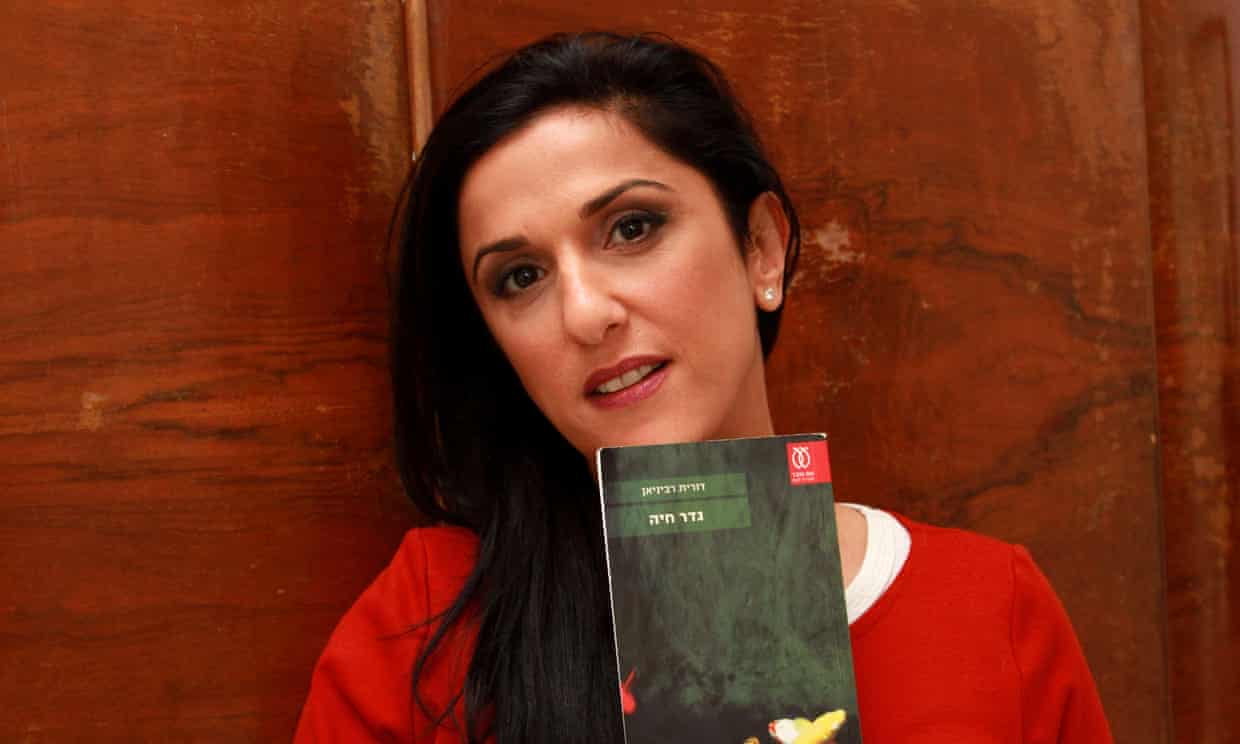

Dorit Rabinyan, whose book about a love affair between a Jewish girl from Tel Aviv and a Palestinian boy from Hebron was banned from Israeli schools. Photo by Gil Cohen Magen/AFP/Getty Images

Why there is still hostility when Jews and non-Jews fall in love

Kil’ayim is the Torah prohibition of mixing things that shouldn’t be mixed. Israeli author Dorit Rabinyan’s experience shows that this extends to love

By Giles Fraser, Loose canon, The Guardian

June 01, 2017

There are many different ways to complete the sentence “I cannot be antisemitic because… ”. All of them are dodgy. For the liberal left, the standard answer is “because I am a committed anti-racist”. For the “alt-right” it is “because I support Israel”. For me it is “because my wife is Israeli” – and I have learned never to say that one. Even “because I am Jewish” is not safe. There is no formulation of the sentence “I cannot be antisemitic because…” that you should trust. Not one.

I am sitting in a tent at the Charleston literary festival with the Israeli writer Dorit Rabinyan. We are “in conversation”, discussing her novel All the Rivers, recently published in English translation. The Charleston festival has this lovely boutique, country-garden feel. Based at the Bloomsbury movement’s Sussex retreat house, this is where the progressive intellectuals of the day discussed big ideas round the kitchen table and swapped bedrooms upstairs. Among them was Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard.

I refer to Woolf because her own casual antisemitism could easily have been dismissed with the “I cannot be antisemitic because…” defence. She was so virulently anti-fascist that the Nazis put her on the Sonderfahndungsliste GB – a list of people to be rounded up after the invasion of Britain. Indeed, her husband was Jewish. Nonetheless, three years after marrying him, she wrote in her diary: “How I hated marrying a Jew – how I hated their nasal voices, their oriental jewellery, and their noses and their wattles.” In her fiction she wrote with revulsion about “the Jew” in the room next door taking a bath and leaving his hairs and a greasy mark in the tub. She wrote about a hooked-nose “little Jew boy” rising up becoming the wealthiest jeweller in England.

In other words, not all antisemites wear a swastika. And the current anxiety that the progressive left has an antisemitism problem is nothing new. Antisemitism is both a constant and a shape-changer. There is no simple ideological inoculation against it.

But it is not just antisemitism that many Jews fear. Many also fear philosemitism. Rabinyan’s book is a sort of Romeo and Juliet, a forbidden love affair between a Jewish girl from Tel Aviv and a Palestinian boy from Hebron. And she knows of what she speaks, because her beautiful novel is actually a semi-fictionalised account of her relationship with the Palestinian artist Hassan Hourani.

“The book tries to express the Jewish fear of losing our identity in the Middle East,” says Rabinyan. And it certainly touched an open nerve in Israel, with the book being banned from schools for describing intimacy between a Jew and a non-Jew. The Ministry of Education explained the ban thus: “Intimate relations between Jews and non-Jews … are seen by large portions of society as a threat on the separate identities [of Arabs and Jews].” Some years before, the same ministry had also banned a children’s book about a parrot and a cuckoo who got married. It referenced “inter-species sex”, they said.

As you can imagine, as a non-Jew married to an Israeli Jew, I take this sort of thing rather personally. And in the course of our conversation, Rabinyan makes a fascinating link between the hostility to Jews and non-Jews having a relationship and the biblical teaching about mixing different things together. The Hebrew word kil’ayim refers to the prohibition of mixing different seeds in the same bed or different types of material in the same cloth. An important part of kosher is the separation of meat and dairy products. Theologically, one could argue that all this is rooted in the fundamental separation of God from the world, of the pure from the impure. That’s why the essential hybridity of the Christian story – of God becoming human – offends Judaism at its core.

This month, it is 50 years since the US supreme court struck down the ban on interracial marriage. Nearly half of US Jews now marry out, and many of them don’t raise their children in the faith. That is what’s behind some of the reaction to Rabinyan’s book. Unfortunately, the continuity of the Jewish people is seen to be threatened by those who fall in love with Jews as well as by those who disparage them.