Are Jews white?

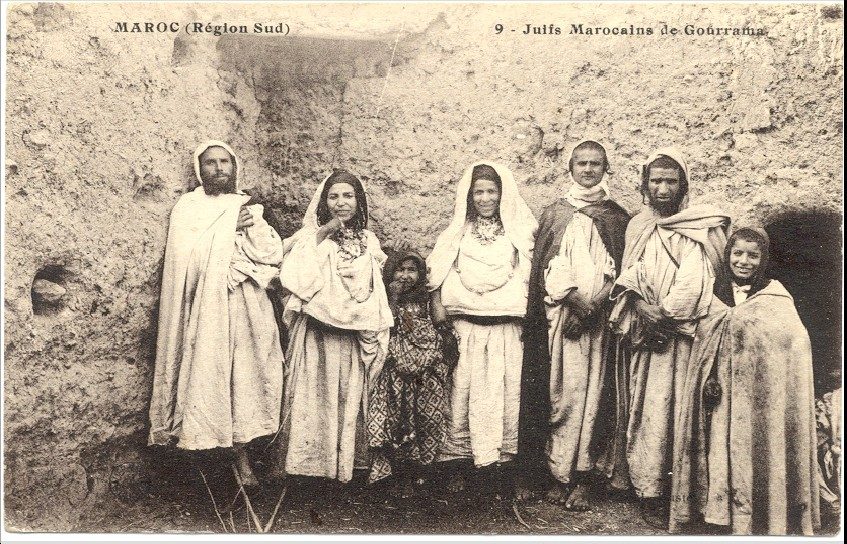

Moroccan Jews early 20th C. The Jews of Morocco, though pressed to immigrate to Israel, were treated with disdain when they arrived. They are still not seen as ‘white’, metaphorically.

Are Jews White Right Now?

By Sara Weissman, Scribe/ Forward

January 05, 2017

After the election, my friend’s younger brother called from Israel. “Are we white?” he asked.

Her immediate response was, “Not anymore.”

As I listened to my friend talk about this exchange, I wasn’t sure which part was more telling, the question or the answer. The question – how we fit into America’s racial landscape as Jews – is an old one. But our specific worries about what our conclusion may be are new. Since the election, the next generation of Jews is asking, “Are we white right now? And, if we’re not white in Trump’s America, what does that mean?”

Trump or no Trump, Jews have always had a complicated relationship with whiteness, first off, because we’re not monolithic. Many Jews identify as Jews of color.

Yet there’s also no getting around it: Many Ashkenazi Jews benefit from white privilege in modern-day America. We’re not getting stopped at traffic lights for searches because we’re Jewish. We don’t face the deep and systemic challenges people of color experience in our country every day. We can walk around with the comforting realization that people likely think of us as white and, if they know we’re Jewish, it’s unlikely to make a difference.

Our white privilege as Jews in America, however, is also pretty newly acquired. No one saw my great grandparents, Romanian Jewish immigrants, as white. The word “kike” was still in fashion when my grandparents were kids. My dad got beat up on the playground for being one of a few Jewish students at his school. Because whiteness is a social construct, its borders – who it includes and excludes – shift over time. I now reap the rewards of a privilege my great grandparents may have hoped for but never imagined.

As a result, many Jews, even those who appear white, simply don’t feel white – no matter how much we benefit from society’s assumption that we are. We have a long communal memory of persecution and our own culture, practices, and jargon that fall outside of mainstream white ‘Murica. Even if Jews still can’t agree (after 5,000 years) whether Jewishness is a religion, culture, or both, it’s our amorphous identity, and many of us subscribe to it as our label of choice.

Meanwhile, the alt-right has definitively decided we’re still not white enough. More than 800 Jewish journalists have been harassed on social media with Holocaust imagery and conspiracy theories about our grand cabal of world-dominators. (If Jews rule the world, I haven’t gotten my check in the mail. Just sayin’.) Meanwhile, Steve Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist and the CEO of the alt-right platform Breitbart, didn’t want his kids going to school with Jewish students, according to his ex-wife in a sworn court declaration in 2007.

So, are pale Jews white right now? If whiteness is defined by white privilege, probably. If it’s defined by how we identify, maybe not. And if it’s defined by the alt-right, hells no. Our status is, it’s complicated. But, in the wake of this election, I think we need to ask a different question.

Do we want to be white right now?

Because this weird gray area arguably gives us a choice. We can choose to identify with minorities or we can choose to identify with the majority in power.

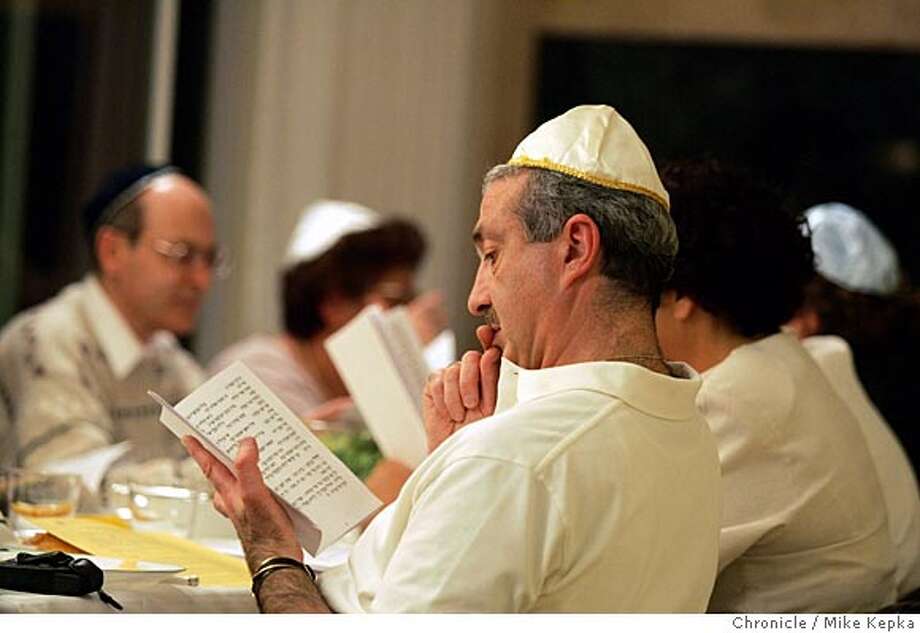

The largest community of Karaites, a sect of non-rabbinical Jews from Egypt, lives in the South Bay, San Francisco. The Karaites’ exodus from Egypt began after the Suez Crisis in the ’50s. Here Zaki Elkodsi reads from the Haggadah during the seder. April 2005 photo by Mike Kepka.

Historically, Jews have had to ask themselves this question time and time again: When a governing entity comes into conflict with other groups, with whom do we side? As a heavily persecuted people, our answer was often whoever would keep us safe or leave us alone. For example, there’s a reason our synagogue services include a prayer for the government. Sure, we can be patriotic and our sages taught good government is key to peace – but we’ve also prayed for the safety of czars, sultans, and kings in the hopes they’d appreciate the gesture and let us be. Particularly in the Middle East and North Africa, Jews made diverse and difficult choices about whether to identify with colonial powers, their neighbors, or both, based on their convictions and what seemed safest at the time.

My two cents: Now that our President-elect won on campaign promises to deport “bad hombres,” ban Muslim immigration, and expunge crime with stop and frisk, it’s high time for American Jews to side with minorities. People of color aren’t blessed with a choice – but, as far as we know, at this moment in history, we are. We can embrace the label recently bestowed on us by the whims of the white privilege fairy, or we can realize what her transient gifts deny others. We can stand with power because it makes us feel safe, or we can find more steadfast solidarity in standing with other communities that face discrimination under this administration.

So, as a white-looking Jew, am I white right now? In Trump’s America, I have no idea. But I’m choosing to answer, “Not anymore.”

This piece originally appeared in New Voices.

In this 2006 picture, members of the restored Sephardi synagogue of Barcelona carry the Torah in the streets of the Catalan city. Photo by Manu Fernandez/AP

For Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, Whiteness Was a Fragile Identity Long Before Trump

By Sigal Samuel, Forward

December 06

“I have lived for 26 years under the illusion that I am unconditionally white…. Recently I have started looking at my face and going, ‘Oh man, do I look too Jewish?’” Sydney Brownstone, the reporter who voiced this question in a recent Blabbermouth podcast, is not alone in wondering this. Many Ashkenazi Jews who have always assumed that they’re white are noticing that they’re not white enough for Donald Trump’s white supremacists. Suddenly, they’re asking themselves: Wait, how white am I, exactly?

To tackle this question, try a little visualization. Picture all American Jews arranged along a spectrum. On one end are the Ashkenazi Jews who identify as white and get coded as white by society. On the other end are the Jews of color who can never pass as white: black Jews, Chinese Jews and others who get read as non-white on the street. In the middle of the spectrum are Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, who sometimes pass as white and sometimes don’t.

As a Mizrahi Jew — my ancestors come from India, Iraq and Morocco — I inhabit that ambiguous middle space. For a long time, it’s been a lonely place to be, since Ashkenazi is Judaism’s default setting in America. It’s also been massively confusing, since I often reap the privileges of being white-passing, even as I get selected for “random additional screenings” by the TSA or for “Where are you really from?” queries from strangers on the street.

But here’s how I think about what’s happening now: Ashkenazi Jews are increasingly getting pushed into the middle space with me. The ascendant discourse of white supremacy, which posits that Jews are not “pure” whites, has thrust them into this space — a space where the lines of your identity are perpetually blurry, where a sense of racial belonging constantly eludes you, and where the category of whiteness is always already in crisis, because your inability to situate yourself cleanly inside it (or cleanly outside it) shows how logically incoherent the category must be.

It’s not a comfortable state to be in — Mizrahi Jews like me get that, because we’ve been in it our whole lives — so it’s not surprising that a lot of Ashkenazi Jews are resisting it. Some are doubling down and insisting that they’re 100% white. Others are taking the opposite tack, insisting that they’re 100% non-white, and that it’s wrong to say they benefit from white privilege. Take Micha Danzig, who wrote in the pages of the Forward, “Ashkenazi Jews have been the victims of European and Western oppression and violence for centuries precisely because they were perceived as not being a part of the ‘white’ world…. Jews are not ‘white.’ We are a tribal people from the Levant.”

There is some validity to that. If your grandparents suffered through the horrors of the Holocaust, then it seems clear that historically your family has not enjoyed white privilege. Still, since World War II, your family likely has been enjoying some amount of white privilege in America, where antisemitism hasn’t been a core facet of the nation’s racial logic the same way that anti-blackness has. And you have to recognize the social structures that continue to confront people around you on a daily basis, even if your own family history is tragic.

Besides, why not relish the discomfort of inhabiting this ambiguous middle space? Discomfort can be productive. Let it reveal to you what it’s revealed to Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews for decades: that your dream of fitting snugly into a certain racial category was doomed from the start, because the category of “whiteness” itself is bogus, a social construct with ever-shifting borders — just look at how it fails to consistently contain or exclude you.

Now, notice how recognizing the fragility of your white identity encourages you to ask some tricky questions. Questions like, “If I’m never going to be white enough for the ‘alt-right’ — if, from their perspective, I’ve been inhabiting the middle part of the spectrum all along — then should I really be allying myself with the likes of Steve Bannon? Shouldn’t I instead ally myself with Jews of color — and with people of color in general, and with Muslims and immigrants and all the other primary targets under Trump?”

I’d argue that now is the time to embrace your Jewish distinctiveness, and to embrace the work it pushes you to do with and for others. Some Mizrahi Jews realized long ago that our non-white status should make us natural allies for other non-white groups. My best-case scenario for today’s white supremacist surge is that it will bring more and more Ashkenazi Jews to this same realization, pushing them to reach out to the non-white-passing end of the spectrum. I hope the people on that end reach back.

The Sephardi synagogue in Curacao, southern Caribbean established in the mid 17thC by Portuguese settlers.

How Jews Became White Folks — and May Become Nonwhite Under Trump

By Karen Brodkin, Forward

December 06, 2016

Decades before I wrote the book “How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says About Race in America,” I had an eye-opening conversation with my parents. I asked them if they were white. They looked flummoxed and said, “We’re Jewish.”

“But are you white?”

“Well, I guess we’re white; but we’re Jewish.” Then they wanted to know what I thought I was.

I’m white and Jewish.

My parents were born in 1914, in an America that looked eerily like what Donald Trump seeks to re-create today. They grew up in the ’20s and ’30s, during the Great Depression, in a period when racism, antisemitism and anti-immigrant eugenic beliefs were widespread. Nativism and the belief that Northern and Western Europeans form an innately superior race were mainstream ideas. The masses of Jews and other Southern and Eastern European immigrants who became the foot soldiers of America’s industrial revolution were despised as lesser, not-quite-white races.

Segregation and racial discrimination were the law of the land. They governed institutional practice in all domains of life — including immigration. Hitler embraced these ideas. Concentration camps were their institutionalized practice. My parents’ generation looked over their shoulders continually. They knew antisemites were out there. Not me; I pooh-poohed such fears. We were all real Americans now.

In the wake of World War II, the horrors of Nazism were becoming public and publicly repudiated. Eugenics and political forms of institutional antisemitism lost much of their hold. A good economy and a progressive political climate enabled America to dismantle some aspects of legal discrimination and segregation. One result was that Ashkenazi Jews became white; for a while, in the ’50s, we even became a best-selling flavor of American popular culture. Those benefits weren’t extended to African Americans, Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans and other Asian Americans. Racism itself didn’t take a hit. The category of white just expanded to include Southern and Eastern Europeans. I figured it was permanent.

Now, Trump’s election and the closet of bigotry it has opened raise a question. Have the decades of whiteness we’ve enjoyed affected American Jews and Jewishness permanently, so that Jews would still be considered white, in the sense of still being included among the racially privileged, those safe from persecution?

A white wedding at the Sephardic temple, LA.

For Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, Whiteness Was a Fragile Identity Long Before Trump

By Sigal Samuel, Forward

December 06, 2016

Many have pointed out the chilling parallels between the values and worldviews of the old eugenicists and those of Trump and his supporters. Not least is Trump’s belief that his success comes from good genetics. So, too, are the overt welcomes and dog whistles to racists, xenophobes, misogynists and homophobes expressed by many of his followers, key advisers and Cabinet picks. To many, Trump’s plan to impose a compulsory registry for all Muslims echoes Hitler and yellow stars.

How prominent is antisemitism in this stew of overlapping hatreds? Both the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center reported a wave of harassment, intimidation and hate in the week after Trump’s election. SPLC graphed some 400 incidents reported to it. Anti-immigrant and anti-black attacks constituted more than half the total. There seemed to be only 10 anti-Semitic incidents. I wondered if that means we’re still white.

Then I noticed a much larger but separate category: swastikas. This was weird, because what else is a swastika if not an anti-Semitic symbol? But to Nazis, the swastika was the emblem of a master race. I’d been thinking that many of Trump’s supporters were a loose coalition of bigots. But the prevalent deployment of swastikas can organize a mix of bigots into an atavistic movement that claims to be a master race of white Christians, with a God-given or genetically-given right to rule. If it claims whiteness and Christianity for itself, there’s not much room for Jews.

This and other white “identity” movements have nothing to do with ethnicity or culture. They’re a claim to ownership, power and privilege defined by hatred for whomever it defines as not- white. And that’s even scarier than a coalition of bigots.

One of the greatest privileges of whiteness is that you don’t have to spend all your time and energy defending your collective right to exist. When I first encountered antisemitism, on a pleasant day in Montana in the summer of 1959, I was secure in that privilege. As a bunch of us tossed around softballs, one guy reached out and snagged a ball being thrown to me. “I jewed you!” he shouted joyfully. When I asked what he meant by that, he told me it meant that he was acting like a Jew — grabbing what wasn’t his. I asked him if he’d ever met a Jew. He hadn’t, so I told him that I was Jewish. He was amazed because I didn’t have horns (really). I didn’t experience him as hostile, just dumb. I didn’t have to defend Jews; we were white.

Twenty years later, in North Carolina, a friend told me that many white Southerners still didn’t see Jews as white. Again, this didn’t really bother me. These folks, I thought, just didn’t know any better.

Today, I’d think differently. We need to challenge all bigotry, not least by building inclusiveness and democracy every chance we get.