Terror in Jerusalem

This posting has these items:

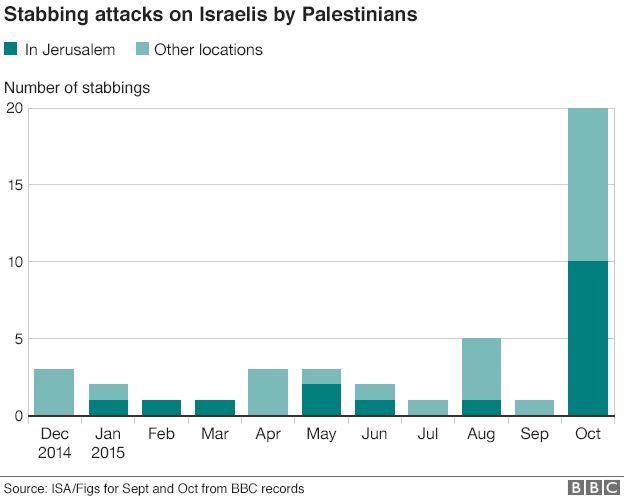

1) BBC: Stabbings of Israelis and Palestinians, graph followed by figures of how many Israelis and Palestinians killed in public in October;

2) Globe and Mail: Fear of violence palpable on both sides of Israel-Palestine divide;

3) BBC: Jerusalem knife attacks: Fear and loathing in holy city;

4) Haaretz: Terror shakes new immigrants who came to Israel to flee antisemitism;

Suspected Ra’anana attacker [see item 4] being taken to the hospital. October 13, 2015. Photo by Allison Kaplan Sommer

32: Number of Palestinians killed, mostly shot dead by security forces, since October 2nd 2015. Source PCHR plus news report Ma’an October 14th.

7: Number of Israeli Jews killed by terrorist acts in October 2015. Source, Jewish Virtual library

Fear of violence palpable on both sides of Israel-Palestine divide

By Patrick Martin, Analysis, Globe and Mail (Canada)

October 15, 2015

Stabbing attacks against Jewish Israelis have tapered off the past two days, but buses in West Jerusalem remain half empty, sidewalks are nearly deserted and the only crowds are outside stores selling pepper spray.

Fear in Israel has been palpable this month as seven Jewish Israelis have been killed in random knife attacks carried out mostly in West Jerusalem by local Palestinians. The word is that Friday might be another “day of rage.”

But, on the other side of town, in the Arab communities of East Jerusalem, the fear is no less real.

More than twice as many Palestinians have died violently in the first half of this month. Some 12 suspects have been killed by security forces at the scene, several others have reportedly been gunned down on suspicion of planning to attack someone.

Earlier this month, a 19-year-old Palestinian named Fadi Alloun was accosted in the early morning by a mob of Israelis, who accused him of carrying out a stabbing some time before. They prodded nearby police to shoot him. They did, seven times, even though a video recording of the incident showed he was wielding no weapon and posed no threat.

“Amidst the violence and unrest, the Israeli army and police are operating on a ‘shoot to kill’ policy,” said Diana Buttu, a Canadian-born Arab Israeli and former adviser to Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas.

Any Palestinian found on the streets of West Jerusalem can expect to be stopped, searched and interrogated repeatedly by police and military patrols – as well as hassled and threatened by civilians.

Zain Said, a greengrocer in the Jabal Mukabbir neighbourhood of East Jerusalem, said he’s afraid to let his children walk alone. “I accompany them every day to their school in Jerusalem, wait there and then walk home with them,” he said.

Mr. Said leaves his own business unattended most of the day. “It doesn’t matter; there’s hardly any customers these days,” he said.

“People feel extremely vulnerable,” said Ms. Buttu, who lives in Ramallah, north of Jerusalem, “even more than they usually do living under Israel’s occupation.”

They’re also upset, she added, that people in the West pay attention to the situation here “only when Israelis are killed and not when Palestinians are killed.”

The cause of Palestinian rage, she insists, is the near-half-century of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, including Arab East Jerusalem.

The rage of some young people is egged on by preachers such as Mohammed Salah in city of Rafah in the Gaza Strip. Last Friday, he brandished a knife during his video-recorded sermon and called on young Palestinians in Jerusalem to attack Jews. “Stab the myths about the temple in their hearts,” he said.

These disparate young people believe they are fighting to save the 1,400-year-old al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock from being torn down to make way for a third Jewish temple.

Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu of Safed – long associated with right-wing and racists comments.

Right-wing Israeli activists, incited by rabbis such as Shmuel Eliyahu of the northern Israeli city of Safed, gather at the site regularly. Two weeks ago, Rabbi Eliyahu declared: “It is feasible and necessary to erect an altar on the Temple Mount today.”

He and his followers want Muslims off the Mount so a new Jewish temple can be erected.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu this week ordered all members of the Israeli parliament, the Knesset, to stay away from the Mount, but not the general Jewish public.

Even Rabbi Shimon Ba’adani, a religious leader of Shas, a movement of ultra-orthodox Sephardi Jews that forms part of the governing coalition, argued this week that the visits by all Jews need to stop. They are what “sparked all the current tumult,” he said.

It’s not the first time this holy site has sparked conflict.

In August, 1929, a dispute over control of the Western Wall, claimed by both Jews and Muslims, led to riots in Jerusalem, Hebron and Safed that left 133 Jews killed, largely by Arab rioters, and 116 Arabs killed, mainly by British security forces.

In September, 2000, a demonstration in favour of the right of Israelis to visit the Temple Mount by Ariel Sharon, then leader of the opposition, led to Palestinian riots. The violence would grow in the coming days into the bloody 2000-04 intifada, in which more than 3,000 Palestinians and about 1,000 Israelis perished.

A growing number of Israeli commentators argue for a prohibition against all Jews going on the Mount. It may be the only way to prevent a slide into real war.

Jerusalem October 13th: a Palestinian man (half way back) rammed his car (at back) into a bus stop and gets out to stab someone (on ground). A private security guard, foreground, shoots him and he dies later of his wounds. Screenshot from security camera.

Jerusalem knife attacks: Fear and loathing in holy city

By Jeremy Bowen, BBC Middle East editor, Jerusalem

Jerusalem is at the heart of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. Both sides see it as their capital. Both venerate religious sites that are also national symbols.

And while it is often possible to ignore the conflict in the beaches and bars of Tel Aviv, the conflict, and the hatred it has engendered, is always strongest in Jerusalem.

Some people like to call it the city of peace. In fact, the holy city is one of the least peaceful places imaginable. Even in quiet times, conflict and hate lie close to the surface.

The scene at the main Israeli bus station in Jerusalem on Wednesday night was a microcosm of the mood of the city. A Palestinian stabbed an Israeli woman.

Police said he was prevented from boarding a bus when the driver locked the doors, then was shot dead by a special patrol unit that raced to the scene.

But fears that another assailant was on the loose in the bus station meant a security alert that lasted a couple of hours.

Emotions in the crowd that gathered outside ranged between anger, fear and defiance.

Some religious men linked arms and danced, singing Jewish songs. I saw about a dozen women, sobbing and shaking, being treated for what looked like panic attacks by medics.

Masked, heavily armed men from another elite unit of the border police ran into the building. I overheard an Israeli boy of about 12, worried, but bravely keeping it together on the phone to his mother. She must have been frantic with worry, and on her way to pick him up. The boy told her he would wait by the Lotto kiosk.

Expanding city

Jerusalem has been simmering dangerously for two years or more. The government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been asserting what it believes is its national right to build homes for Jewish Israelis wherever it decides they are needed in a city that it calls its undivided, eternal capital.

The government’s backing for the expansion of settlements in the sections of Jerusalem captured during the 1967 war, and classified as occupied territory by most of the rest of the world, has transformed some districts.

Palestinians feel they are being squeezed out of their home. They believe that their territory is being eaten up by Israel’s appetite for land, and loath what they see as a national ideology designed to enforce the dominance of Israel and Judaism.

Security blocks and checkpoints are being installed around and inside East Jerusalem. Photo Getty images.

After two weeks of violence, the Israeli government, under a lot of pressure to act from citizens who with good reason fear for their safety, has beefed up security in Jerusalem. A senior official told me that there might be no perfect security solution.

That’s partly because it is harder to stop determined individuals than organisations that can be penetrated by Israel’s efficient intelligence services.

But it is also because for almost 50 years, Israel has worked hard to unify West Jerusalem with the occupied east side of the city. Public transport and road systems have been integrated.

Jews have settled alongside areas that were wholly populated by Palestinians, in some cases right in the heart of Palestinian neighbourhoods.

Normal teenager

So why have Palestinians carried out appalling crimes, seemingly random attacks on passers-by simply because they are Israeli Jews? Some of the assailants have been well-educated young people without security records.

When I met Khaled Mahania, the father of 15-year-old Hassan Mahania, who attacked and badly wounded young Israelis in a settlement in East Jerusalem, he is unable to explain.

Hassan was shot dead as he carried out the attack; his 13-year-old cousin and accomplice was run down by a car and badly hurt.

Police and emergency services at the scene of a stabbing in Ra’anana which wounded one person. The assailant was subdued by people nearby, October 13, 2015. Photo by Allison Kaplan Sommer

Terror shakes new immigrants who came to Israel to flee antisemitism

‘We came here to feel safe. Now my children refuse to walk to school alone, just like they did in Paris,’ French émigré says after twin attacks in Ra’anana.

Allison Kaplan Sommer, Haaretz

October 13, 2015

Frightened by the wave of antisemitism in France, Janine Solomon moved to the quiet Israeli suburb of Ra’anana two years ago. Standing in a crowd of frightened and angry residents on the town’s main street in the aftermath of the first of two stabbing attacks in the city on Tuesday morning, she joined their chorus of protests and cries for revenge.

“We came here to feel safe. Now my children refuse to walk to school alone, just like they did in Paris. It’s like France here now. It’s dangerous!”

“Put a checkpoint at the entrance to Ra’anana. No Arabs allowed.”

There was angry and emotional chatter around the scene of the attack from new immigrants like Solomon in French, Spanish and English alongside the shouts in Hebrew as the ambulances carrying the victim and the terrorist made their way to the hospital on the city’s main artery, Achuza Street, which had been closed off to all traffic.

Police and security personnel had taken the wounded terrorist and surrounded him, protecting him from the furious bystanders, until the ambulance arrived and he could be put inside – a process that took nearly an hour. As he was wheeled into the ambulance, the angry shouts rang out, “Take him straight to the cemetery, forget about the hospital!”

The hero of the moment was real estate agent Michael Rahavi. When Rahavi heard the screams of the stabbing victim at the bus stop in front of his Achuza Street office, steps away from the bus stop where the assault was taking place, he grabbed the first useful object he saw in his office – an umbrella – dashed out and used it to subdue the attacker until police arrived minutes later. Rahavi said that “I hit him with it and others kicked him,” he said. “If I had a gun, I would have fired.”

The terror attack and its aftermath is a scene that is depressingly familiar in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv or the West Bank, but until recent weeks, have been extremely rare and nearly alien to those who chose to live in places like Ra’anana, Holon, or Afula – which are neither major cities, nor settlements on contested land. Ra’anana in particular is a magnet for thousands of well-heeled immigrants from across the world – South Africa, the United States, Great Britain, and most recently, France, looking for a peaceful place to raise families.

Both immigrants and locals in Ra’anana, during previous waves of attacks, joked regularly that their suburban home is simply too boring to be of interest to terrorists, and most heave a sigh of relief as they arrive home safely from Tel Aviv or Jerusalem.

But Tuesday morning’s events shattered any sense of immunity from the unrest that is rocking the rest of the country. The bubble of illusory security had burst.

As the crime scene tape was removed, the blood washed from the sidewalk, and Achuza street reopened to traffic, Ra’anana Mayor Ze’ev Bielski stood in the middle it, speaking to the press reassuringly promising to quickly restore order.

Next to him, the stunned and angry residents of his city stood around and scoffed. “Only God can keep us safe now,” said one. Another said that only one measure could make him feel secure. “Put a checkpoint at the entrance to Ra’anana,” he said. “No Arabs allowed.”