Apocalypse now!

Gershon Salomon proclaims a Jewish right to Temple Mount:’The Temple Mount has been a source of war and conflict for centuries and is likely one of the most valuable pieces of real estate on the planet. Today on Jewish Voice join Rabbi Jonathan Bernis and Gershon Salomon, founder of The Temple Mount and Land of Israel Faithful Movement as they discuss this hotly debated topic. If the temple is to be rebuilt how can it possibly co-exist with the Muslim Dome of the Rock or will the dome, one of the holiest sites in Islam, have to come down?’ Gershon Salomon Israel Program (June 16, 2014), youtube

Why rebuilding the Temple would be the end of Judaism as we know it

The current drive of Jews, both Orthodox and secular, to ascend to the site of the Holy Temple and rebuild it, reflects a sea change in the Zionist camp.

By Tomer Persico, Haaretz

November 13, 2014

Gershom Scholem, the scholar of Jewish mysticism – “Whether or not Jewish history will be able to endure this entry into the concrete realm without perishing in the crisis of the messianic claim, which has virtually been conjured up.” The entry into history to which Scholem refers is the establishment of the state and the ingathering of the exiles, borne, as they were – notwithstanding their secular fomenters and activists – on the wings of the ancient Jewish messianic myth of the return to Zion. However, when Scholem published the essay “Toward an Understanding of the Messianic Idea in Judaism,” in 1971, the adjunct to the question was the dramatic freight of Israel’s great victory in the Six-Day War, four years earlier.

It was a period of euphoria, as sweeping as it was blinding. Yeshayahu Leibowitz, the religiously observant public intellectual, immediately warned the country’s leaders against the dangers of ruling by force a population of more than a million Palestinians. Scholem, though, was more concerned about the danger of a physical return to the Temple site. While Leibowitz lamented the mass Sabbath desecration caused by buses filled with Israelis coming to view the wonders of the Old City (and buy cheap from its Arab vendors) – Scholem was far more concerned by the sudden intrusion of Mount Moriah into the Israeli political arena. Possibly, as a scholar of kabbala, he had a better grasp than Leibowitz of messianic eros and of Zionism’s susceptibility to its allure.

From its inception, the Zionist movement spoke in two voices – one pragmatic, seeking a haven for millions of persecuted Jews; the other prophetic, attributing redemptive significance to the establishment of a sovereign state. Whereas the shapers of Western culture, from Kant to Marx, perceived individual liberation in an egalitarian regime as the proper secularization of religious salvation, for the Jewish collectivity, this turned out to be a false hope.

Against the background of surging antisemitism, at the end of the 19th century, many Jews discarded the message of emancipation in favour of an effort to create a national home for the Jewish people. This solution, however, bore messianic implications, for it is precisely the founding of an independent Jewish kingdom that is the salient sign of Jewish redemption. The Christians received their deliverance, and the Jews – including those who would rather leave their religion in the museum of history – will receive theirs.

Well aware of the messianic implications of their efforts, the shapers of the Zionist movement tried to neutralize them from the outset. In his Hebrew-language book “Zion in Zionism,” the historian Motti Golani reveals the ambivalent attitude toward Jerusalem harboured by Zionist leaders. Theodor Herzl himself, the founder of modern political Zionism, was not convinced that the establishment of a Jewish political entity in Palestine would best be served by Jerusalem’s designation as its capital; and even if it did, he wanted the Holy Basin to function as an international centre of religion and science.

Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, went even further. He maintained that if the holy places were under Israeli sovereignty, Zionism would not be able to design its capital according to its progressive world-view. He espoused the partition of Jerusalem in order to preclude Israeli sovereignty over the Temple Mount. When such Zionist leaders such as Menachem Ussishkin and Berl Katznelson assertively took the opposite stance, Ben-Gurion retorted, “To our misfortune, patriotic rhetoric surged in Jerusalem – barren, hollow, foolish rhetoric about a productive national project.”

Years later, in the Six-Day War, Defence Minister Moshe Dayan hesitated at length before ordering the capture of the Temple Mount. “What do I need all this Vatican for?” he said, expressing the classic Zionist approach to the subject.

From the start, though, there were voices that demanded not only sovereignty over all of Jerusalem, but also the completion of the redemptive process by force of arms. Before Israel’s establishment, such calls emanated from the fascist wing of the Zionist movement (fascism wasn’t yet a curse word but a legitimate ideology). In the 1930s, figures like the journalist Abba Ahimeir and the poet Uri Zvi Grinberg, the founders of Brit Habiryonim (Union of Zionist Rebels), toiled not only to bring Jews into the country and to acquire arms for an armed struggle against the British. They also staged demonstrations in which the shofar was blown at the Western Wall at the end of every Yom Kippur (just as it is in the synagogue), a custom that was later continued by the Irgun underground militia led by Menachem Begin.

Grinberg, a poet who was considered a prophet, wrote mythic works that sought to fashion an organic conception of a nation that had been resurrected around its beating-bleeding heart, namely, the Temple Mount void of the Temple. Grinberg tried “to renew our people’s ancient myth,” the literary scholar Baruch Kurzweil would write years later. Kurzweil understood well that despite the superficial secularization to which the Zionist movement had subjected the Jewish tradition, the imprint of the ancient beliefs continued to reside within it, like a dormant seed awaiting water. Grinberg’s poetry was like dew that brought those seeds to life in those who were ready for the transformation. The revival of the myth in Grinberg’s poetry, Kurzweil observed, “does not bear only an aesthetic or religious-moral role. The actualization of the myth bears salient political significance.”

That political import was given explicit expression in “The Principles of Rebirth,” which Avraham “Yair” Stern wrote as a constitution for the Lehi, the pre-state underground organization he headed. The full document, published in 1941, set forth 18 points that in Stern’s view would be essential for the Jewish people’s national revival – from unity, through mission, to conquest. The 18th and final principle calls for “building the Third Temple as a symbol of the era of full redemption.” The Temple here constitutes a conclusion and finalization of the process of building the nation on its soil, in pointed contrast to the path of Herzl and Ben-Gurion.

Below, a design for ‘the third temple’ by Yisrael Hawkins, for which he has USA and Israeli patents. Hawkins (formerly Buffalo Bill Hawkins) is an American who established the House of Yahweh in Texas to spread Biblical prophecies.

Topsy-turvy Zionism

A point very much worth noting is that these modern proponents of a rebuilt Temple were not themselves religiously observant, at least not in Orthodox terms. They aspired not to a religious revival but to a national one, and the mythic sources fuelled their passion for political independence. For them, the Temple was an axis and a focal point around which “the people” must unite.

In a certain sense, they simply took secular Zionism to its logical conclusion – and in so doing, turned it topsy-turvy. As noted above, Jewish redemption, including its traditional form, is based largely on a national home and on sovereignty. According to the tradition, one measure of this sovereignty is the establishment of a Temple and a monarchical government descended from the House of David. Zionism wanted to make do with political independence, but the stopping point on the route that leads ultimately to a monarch and a temple is largely arbitrary, based as it is on pragmatic logic and liberal-humanist values. For those who don’t believe in realpolitik and are not humanists, the push toward end times is perfectly logical.

Mainstream Zionism, in other words, wished to make use of the myth as far as the boundary line of its decision: yes, to ascend to the Holy Land, and yes, to declare political independence, but no to searching for Messiah Ben David and no to renewing animal sacrifices. Ahimeir, Grinberg, Stern – and Israel Eldad after them – were not content with this. They believed that the whole vision must be realized. Less religious than mythic Jews, they wanted to push reality to its far end, to reach the horizon and with their own hands bring into being the master plan for complete redemption. And redemption is the point at which hyper-Zionism becomes post-Zionism.

As Baruch Falach shows in his doctoral thesis (written in 2010 at Bar-Ilan University), one ideological-messianic line connects Ahimeir, Grinberg, Stern and Eldad to Shabtai Ben-Dov and the Jewish underground organization of the early 1980s, which among other things wanted to blow up the Dome of the Rock, the Muslim shrine on the Temple Mount.

In the figure of Ben-Dov – a formerly secular Lehi man who became an original radical, religious-Zionist thinker – the torch passes from messianic seculars to the religiously observant. It was Ben-Dov, who became religious himself, who ordered Yehuda Etzion, a member of the Jewish underground, to attack the third-holiest site in Islam, in order to force God to bring redemption. “If you want to do something that will solve all the problems of the People of Israel,” he told him, “do this!” And Etzion duly set about planning the deed.

This apocalyptic underground messianism differs from the messianism of Gush Emunim (“Bloc of the Faithful,” the progenitors of the settler movement), as conceived by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine and the founder of Mercaz Harav Kook Yeshiva in Jerusalem.

Gush Emunim, loyal to the teaching of Rabbi Kook and of his son, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, developed a mamlakhti (“state-conscious”) approach, according to which, even though its activists alone understand the political reality and its reflection in the upper worlds, it is not for them to impose on the nation of Israel measures that the nation does not want. As settler-activist Ze’ev Hever put it, after the underground was exposed, “We are allowed to pull the nation of Israel after us as long as we are only two steps ahead of it… no more than that.”

Accordingly, the settlement project in Judea and Samaria is considered pioneering but not revolutionary. And, indeed, we should remember that the settlement enterprise had the support of large sections of the Labor movement, as well as of such iconic cultural figures as the poet Natan Alterman and the composer-songwriter Naomi Shemer. This was not the case with Temple matters, which are far more remote from the heart of the people that dwells in Zion. In addition, Kook-style messianism shunned the Temple Mount for halakhic (Jewish-legal) reasons. Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, like his father, ruled that it is forbidden to visit the mount. Here, too, Ben-Dov and Etzion followed a radically different path.

Furthermore, before 1967 – and afterward – all the leading poskim (rabbis who issue halakhic rulings), both ultra-Orthodox and from the religious-Zionist movement, decreed as one voice that it is forbidden to visit the Temple Mount, for the same halakhic reasons. This was reiterated by all the great rabbinic figures of recent generations – Rabbis Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, Ovadia Yosef, Mordechai Eliahu, Eliahu Bakshi Doron, Moshe Amar, Avraham Shapira, Zvi Tau and others.

The halakhic grounds have to do with matters of defilement and purification, but even without going into details, it should be clear that in the most fundamental sense sanctity obliges distance rather than proximity. The holy object is what’s prohibited for use, fenced-off, excluded. Reverential awe requires halting prior to, bowing from afar, not touching and not entering. “The people cannot come up to Mount Sinai, for You warned us saying, ‘Set bounds about the mountain and sanctify it,’” Moses asserts in Exodus before he – and he alone – ascends the holy mountain to receive the Torah.

Exalted totem

It is not surprising, then, that the first group advocating a change in the Temple Mount status quo did not spring from the ranks of the religious-Zionist movement. The Temple Mount Faithful, a group that has been active since the end of the 1960s, was led by Gershon Salomon, a secular individual, who was supported – how could it be otherwise? – by former members of the Irgun and Lehi. It was not until the mid-1980s that a similar organization was formed under the leadership of a religious-Zionist rabbi (the Temple Institute, founded by Rabbi Yisrael Ariel) – and it too remained solitary within the religious-Zionist movement until the 1990s.

Indeed, in January 1991, Rabbi Menachem Froman could still allay the fears of the Palestinians by informing them (in the form of an article he published in Haaretz, “To Wait in Silence for Grace”) that, “In the perception of the national-religious public [… there is] opposition to any ascent to the walls of the Temple Mount… The attitude of sanctity toward the Temple Mount is expressed not by bursting into it but by abstinence from it.”

No longer. If in the past, yearning for the Temple Mount was the preserve of a marginal, ostracized minority within the religious-Zionist public, today it has become one of the most significant voices within that movement. In a survey conducted this past May among the religious-Zionist public, 75.4 percent said they favor “the ascent of Jews to the Temple Mount,” compared to only 24.6 percent against. In addition, 19.6 percent said they had already visited the site and 35.7 percent that they had not yet gone there, but intended to visit.

A model of the proposed Third Temple on display at the Temple Institute in Jerusalem. Director of the institute Rabbi Chaim Richman leads daily ‘aliyot’ up the Temple Mount for tourists, nationalists and the religious.

The growing number of visits to the mount by the religious-Zionist public signifies not only a turning away from the state-oriented approach of Rabbi Kook, but also active rebellion against the tradition of the halakha. We are witnessing a tremendous transformation among sections of this public: Before our eyes they are becoming post-Kook-ist and post-Orthodox. Ethnic nationalism is supplanting not only mamlakhtiyut (state consciousness) but faithfulness to the halakha. Their identity is now based more on mythic ethnocentrism than on Torah study, and the Temple Mount serves them, just as it served Yair Stern and Uri Zvi Grinberg before them, as an exalted totem embodying the essence of sovereignty over the Land of Israel.

Thus, in the survey, the group identifying with “classic religious Zionism” was asked, “What are the reasons on which to base oneself when it comes to Jews going up to the Temple Mount?” Fully 96.8 percent replied that visiting the site would constitute “a contribution to strengthening Israeli sovereignty in the holy place.” Only 54.4 percent averred that a visit should be made in order to carry out “a positive commandment [mitzvat aseh] and prayer at the site.” Patently, for the religious Zionists who took part in the survey, the national rationale was far more important than the halakhic grounds – and who better than Naftali Bennett, the leader of Habayit Hayehudi party, serves as a salient model for the shift of the centre of gravity of the religious-Zionist movement from halakha to nationalism?

How did the religious-Zionist public undergo such a radical transformation in its character? A hint is discernible at the point when the first significant halakhic ruling was issued allowing visits to the Temple Mount. This occurred at the beginning of 1996, when the Yesha (Judea, Samaria, Gaza) Rabbinical Council published an official letter containing a ruling that visiting the Temple Mount was permissible, accompanied by a call to every rabbi “to go up [to the site] himself and guide his congregation on how to make the ascent according to all the restrictions of the halakha.”

Motti Inbari, in his book “Jewish Fundamentalism and the Temple Mount” (SUNY Press, 2009), draws a connection between the weakening of the Gush Emunim messianic paradigm, which was profoundly challenged by the Oslo process between Israel and the Palestinians, and the surge of interest in the mount. According to a widely accepted research model, disappointment stemming from difficulties on the road toward the realization of the messianic vision leads not to disillusionment but to radicalization of belief, within the framework of which an attempt is made to foist the redemptive thrust on recalcitrant reality.

However, the final, crushing blow to the Kook-based messianic approach was probably delivered by the Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, in 2005, and the destruction of the Gush Katif settlements there. The Gush Emunin narrative, which talks about unbroken redemption and the impossibility of retreat, encountered an existential crisis, as did the perception of the secular state as “the Messiah’s donkey,” a reference to the parable about the manner in which the Messiah will make his appearance, meaning that full progress toward redemption can be made on the state’s secular, material back.

In a symposium held about a year ago by Ir Amim, an NGO that focuses on Jerusalem within the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Haviva Pedaya, from the Jewish history department of Ben-Gurion University in Be’er Sheva, referred to the increasing occupation with the Temple Mount by the religious-Zionist movement after the Gaza pull-out.

“For those who endured it, the disengagement was a type of sundering from the substantial, from some sort of point of connection,” she said. “For the expelled, it was a breaking point that created a rift between the illusion that the substantial – the land – would be compatible with the symbolic – the state, redemption.” With that connection shattered, Pedaya explains, messianic hope is shifted to an alternative symbolic focal point. The Temple Mount replaces settlement on the soil of the Land of Israel as the key to redemption.

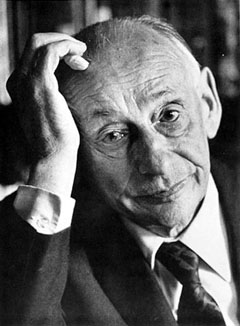

Gershom Scholem, 1897-1982

Gershom Scholem, 1897-1982

Many religious Zionists are thus turning toward the mount in place of the belief in step-by-step progress and in place of the conception of the sanctity of the state. The Temple Mount advocates are already now positing the final goal, and by visiting the site and praying there they are deviating from both the halakhic tradition and from Israeli law. State consciousness is abandoned, along with the patience needed for graduated progress toward redemption. In their place come partisan messianism and irreverent efforts to hasten the messianic era – for apocalypse now.

And they are not alone. Just as was the case in the pre-state period, secular Jews are again joining, and in some cases leading, the movement toward the Temple Mount. Almost half of Likud’s MKs, some of them secular, are active in promoting Jewish visits there. MK Miri Regev, who chairs the Knesset’s Interior and Environment Committee, has already convened 15 meetings of the committee to deliberate on the subject. According to MK Gila Gamliel, “The Temple is the ID card of the people of Israel,” while MK Yariv Levin likens the site to the “heart” of the nation. Manifestly, the division is not between “secular” and “religious,” and the question was never about observing or not observing commandments. The question is an attempt to realize the myth in reality.

Assuaging Ben-Gurion’s concerns, Israel remained without the Temple Mount at the end of the War of Independence in 1948. Not until the capture of East Jerusalem in 1967 did it become feasible to implement the call of Avraham Stern, and the ancient myth began to sprout within the collective unconscious. After almost 50 years of gestation, Israel is today closer than it has ever been to attempting to renew in practice its mythic past, to bring about by force what many see as redemption. Even if we ignore the fact that the top of the Temple Mount is, simply, currently not available – it must be clear that moving toward a new Temple means the end of both Judaism and Zionism as we know them.

The question, then, to paraphrase Gershom Scholem’s remark, with which we began, is whether Zionism will be able to withstand the impulse to realize itself conclusively and become history.

(This is the first of two parts on the subject of the Temple Mount. Part II will appear next week.)