Call for justice or pointless tantrum? BDS reviewed

This is a slightly revised version of comments presented as part of the event “Palestine Solidarity: A Faculty Roundtable and Student Q & A,” held at the CUNY Graduate Center on 17 October. The discussion was organized by a group of students involved with a resolution currently before the Doctoral Student Council at the Graduate Center, endorsing the academic and cultural boycott of Israel. I want to dedicate my remarks to these courageous students, who are engaged in organizing work that is at best thankless and at worst dangerous, given the current climate of hostility in the US academy—and, beyond that, to all those who struggle for justice in Palestine.

By Anthony Alessandrini, Jadaliyya

October 22, 2014

I begin with moment from my graduate student days, when I had just started working with Students for Justice in Palestine at New York University. This would have been the autumn of 2002, at a time when I was thinking and talking and reading and working my way towards a position on the struggle for justice in Palestine, a struggle that I supported but that I sometimes felt I was still too ill-informed about. I was passing out fliers at NYU in support of Birzeit University’s Right to Education Campaign. I was still fairly new to Palestine solidarity activism, but I had already gotten used to some of the hostile reactions, from the man who growled at me, “They should close their schools! All they teach them there is to hate Jews!” to those who simply spat on the sidewalk in front of me. Amidst all this (along with, of course, many sympathetic reactions), a somewhat older, well-dressed man approached and began asking a series of sophisticated questions regarding the goals and grounding of the campaign, as well as my own positions. At a certain point, he gestured towards a small lapel pin in the buttonhole of his jacket. “You understand what this says?” he asked me with a smile. I told him that I recognized it as the logo of Peace Now, although I didn’t read Hebrew. “But you are Jewish?” he asked. No, I told him, as it happened, I wasn’t. At this point, he looked at me more closely, with a puzzled expression on his face. “But you’re not an Arab?” No, as it happened, I wasn’t. His expression had by now turned to one of pure incredulity. “But then, why do you…?” In my memory of the exchange, he didn’t even bother to finish the question; instead, he gave an eloquent shrug of the shoulders.

The unfinished question of my interlocutor—“Why do you care?”—is one that I have spent a great deal of time thinking about. It is the guiding question of what we might call international solidarity, not only in the case of Palestine, but in so many other instances as well. What makes it a specific sort of question in this specific case is the circumstance that baffled my interlocutor: I do not have any sort of identitarian claim to make regarding an issue that, for so many, is a deeply personal one. Lacking such an identitarian claim, why should I care?

I have been thinking recently about this exchange, in part because I have found myself, together with other scholars who work in and around the field of Middle East studies and who are supporters of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS), placed on a blacklist organized by the AMCHA initiative*. It is a list that has been widely circulated by AMCHA and other affiliated organizations, with the stated aim of “protecting Jewish students.” To their credit, the list-makers set things out quite clearly: “Students who wish to become better educated on the Middle East without subjecting themselves to anti-Israel bias, or possibly even antisemitic rhetoric, may want to check which faculty members from their university are signatories before registering.”

I want to pause here to address those who like to propagate the argument that the academic and cultural boycott of Israel amounts to a “blacklist” aimed at Israeli academics. Please look at the AMCHA list. This is what an actual blacklist looks like. It names us by name and explains precisely what, in the eyes of the list-makers, we should not be allowed to do—in this case, teach students who are interested in Middle East studies—based solely upon a political position we have espoused. Those of us who support the academic and cultural boycott of Israel, by contrast, have scrupulously and continuously made it clear that it does not, and will not, target individual Israeli academics; indeed, this is a fundamental guideline of the academic boycott call.

I want to say this about finding myself on the AMCHA blacklist: on the intellectual level, I was able to understand that this was simply another intimidation tactic aimed at silencing Palestine solidarity on US campuses. It was also clear to me that as individual academics, we were just small fish for a group like AMCHA; the real goal for pro-Israel political groups is to attack funding for Middle East studies centers. But on a deeper level, none of this helped. What I felt, mostly, was heart-sick.

My response has been to revisit, with renewed zeal, the question with which I began. AMCHA has its answer to the question of why I care about Palestine: antisemitism. It is a deeply dishonest and disingenuous accusation, but I will do my best to refashion this into an invitation to renew my critical thinking around the question of solidarity. Why do I care?

I can of course answer—indeed, have sometimes answered—that, as a citizen of the United States, I have a particular responsibility to care, given that the actions of the Israeli state are underwritten and enabled by the unwavering economic, military, and political support of the US government. This is part of the answer, but to me, it is not enough. I am not satisfied to ground my solidarity in the accident of my citizenship, and moreover, I think of my solidarity as linked to a global Palestine solidarity movement.

The best answer I have—and I imagine it was part of whatever I said in response to my interlocutor all those years ago—is to say that my solidarity is grounded in a call for justice. I would like to think that the best work I do, as a teacher and scholar and writer and editor, circles around this question of justice. More concretely, though, as I have had the chance to work with others committed to Palestine solidarity work, I have come to see my own commitment as linked inextricably to my larger commitment to anti-racism and anti-colonialism (or, if you prefer, decolonization). I am certainly neither the first nor the last to make this link, although in my own thinking it took some time and effort to put the pieces together. But this notion of Palestine solidarity as a form of anti-racism and anti-colonialism is worth repeating and repeating in the US context (including—especially—the US academic context).

I have a simpler answer to the question of why I support the call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions. I support it precisely as a call. You can read it here. Simply put, the call is one made in the name of and on behalf of a set of principles and goals that I wholeheartedly support, and so supporting this call was, and is, a very easy decision.

However, there are two things that might be worth saying about my support for BDS, given the responses that the movement has occasioned from its opponents in the US academy. The first is that I see my support for the academic and cultural boycott as being grounded very clearly in a set of positive values. Because the particular tactics of boycott and divestment involve certain kinds of stoppages and refusals—the refusal, for example, to lend one’s support, either as an academic or as a consumer, to certain institutions that benefit from injustices—some opponents have painted the BDS movement as a sort of negative, nihilistic force. But needless to say, struggles for justice have time and again used “negative” actions—strikes, boycotts, sit-ins, occupations of public spaces—precisely in the name of the positive values that they are struggling to bring into existence. In this sense, the academic boycott, like similar campaigns aimed at apartheid South Africa, is a positive action aimed towards the advancement of justice. The goal, if we can put it this way, is to make justice come as quickly as possible—and when one recalls that the first international congress in solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa was held in 1959, one gets a sense of how even those struggles that have met with some success have been agonizingly slow.

The second point—and it should be obvious, but I suppose this needs to be said as well—is that my support for BDS does not somehow exhaust my supply of caring, or of solidarity. I care deeply about BDS, and I care very deeply about many other things too. Certainly, deep thinking about the problem of selective solidarity is part of the responsibility of any solidarity movement. But the very fact that, as a supporter of BDS, I find it necessary to state that my commitment to BDS does not exhaust my commitment to other political struggles says something about the staying power of one particular claim made by BDS opponents: that the BDS movement unfairly “singles out” Israel for criticism and sanction.

It needs to be said that the “singling out” argument is, more often than not, an implicit way of making a claim about antisemitism without actually saying as much. To ask “Why are you singling out Israel?” is in many ways to put forward what is meant to function as a rhetorical rather than a real question: the very posing of the question contains its implicit answer. But let us take it seriously as a question that can be refashioned into one that is not simply rhetorical—after all, my own academic work has lately focused on questions of singularity and solidarity, which makes me receptive to addressing this “singling out” accusation. So I will say three things about this question of the BDS movement unfairly “singling out” Israel.

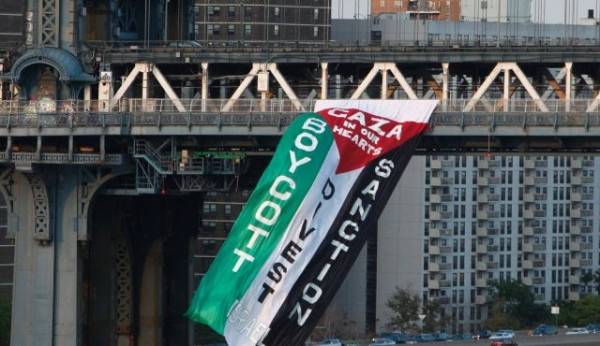

From Stop the Wall.org, Vizualising Palestine.

The first point is the simplest one: the call to boycott Israeli academic and cultural institutions is precisely a call for solidarity. The proper response to such a call for solidarity is either to pledge one’s support, if one is able to offer this support, or to reject the call, if one is not able to do so. The proper response to a call for solidarity is not to immediately ask it to address all other similar foreseeable situations. To adapt one of the points made on an excellent FAQ sheet produced by anthropologists who support the academic boycott: when Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association called for a boycott of grapes, the proper political response would not be to immediately ask: what about apples? This is not to say that we would not need to also talk about apples—that is to say, such a call for solidarity in no way excuses us from doing the work of pursuing all of the other related issues, or from offering our solidarity in other instances. This is certainly true of BDS, and supporting the academic boycott in no way exhausts one’s ability to pursue all sorts of other political commitments. But to immediately, as an initial response to a call for solidarity, ask “but what about all those other things?” is to do a sort of violence to the call itself. It is, quite simply, a form of refusal that does not have the courage to present itself as such.

My second point is a related one. The argument about “singling out,” it seems to me, posits a theoretical person who only signs BDS petitions, and only cares about justice when it comes to the question of Palestine. I suppose such a person may exist, but I have certainly never met her or him. When one looks across the broad spectrum of the Palestine solidarity movement, and the networks and associations that have come to support the academic boycott, what one sees are a series of people engaged in a multitude of struggles for social justice.

It is this question of the struggle for justice that leads to my third and final point. Those who ask why the BDS movement is “singling out” Israel are in fact implicitly admitting that the state of Israel has in fact done something worthy of sanction. In other words, this is not an argument based on the claim that Israel has not done bad things (there are those who do say this, but that’s another argument); it is a way of saying: Israel has done things that are worthy of being sanctioned, but what about all these other bad things that other states have done? To which the answer should be: yes, by all means, let’s talk about all those other things. But regarding this particular set of bad things done by the state of Israel: if you are against BDS, then what do you propose as a way to actively address and ameliorate the injustices being perpetuated? And if those who oppose BDS—especially those who claim to also oppose the occupation while vociferously attacking those of us who support the academic and cultural boycott—refuse to provide an alternative beyond merely offering vague variations on “peace” and “dialogue,” then they should be honest enough to admit that they simply do not care enough about these injustices to want to actively intervene to try to bring them to an end. This is, we might say, a vague and wishful sympathy that never even approaches the point of true solidarity.

Again, I am hardly the first to suggest that the repetition of this charge of singling out Israel masks a position that maintains we simply should do nothing at all, and that is overall satisfied with the status quo. But I think this is a point that needs to be clearly articulated in the current climate. The BDS movement in general, and the movement in favor of an academic and cultural boycott in particular, is a response to a call to end certain injustices. It presents itself, quite clearly, as a call motivated by a set of circumstances in which these injustices have been, and continue to be, committed with almost complete impunity. One of the heartbreaking things about revisiting the original Palestinian Civil Society Call for BDS, issued in July 2005, is that it repeatedly refers to the ongoing construction of the apartheid wall, and to the 2004 decision of the International Court of Justice declaring the wall illegal. Nearly a decade later, the wall has long been completed; it is now just another fact on the ground. This exemplifies the state of impunity that the movement for BDS is struggling to bring to an end, through an approach that relies on a growing popular movement rather than appeals to states or international organizations. Junot Díaz, who recently declared his support for the academic and cultural boycott, has described the importance of this popular movement to end impunity:

If there exists a moral arc to the universe, then Palestine will eventually be free. But that promised day will never arrive unless we, the justice-minded peoples of our world, fight to end the cruel blight of the Israeli occupation. Our political, religious, and economic leaders have always been awesome at leading our world into conflict; only we the people alone, with little else but our courage and our solidarities and our invincible hope, can lead our world into peace.

Let me finish where I began. Why do I care? I find in the call for an academic and cultural boycott of Israel a call for justice, as well as a method aimed at achieving this justice.

BDS and the politics of radical gestures

Boycotts and divestment can be useful tools for righting wrongs, but they are apolitical tantrums in cases of right versus right.

By Todd Gitlin, Tablet [This article has been widely reposted including by Third Narrative, Reut Institute and Scholars for Peace in the Middle East.]

October 27, 2014

Boycotts and divestments appeal to ideals of citizenship. Vote with your money. Make perpetrators of injustice pay a price. Raise the stakes so that, when they get their calculating minds around a cost-benefit analysis, they decide the cost is too steep. Often such campaigns are constructive.

Others channel anger into postures of virtue that detract from a just end. They demand not changes of policy but the disappearance of one party. These are gestures—a stamping of the collective foot. Repeated enough, such gestures can herald crimes more hideous than what the protesters oppose.

The Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, triggered by Rosa Parks, succeeded in convincing the authorities to end racial segregation. The city knew just what it had to do to end the boycott: stop shunting blacks onto the back of the bus. In the end, the courts ordered desegregation, and the city buses, with new seating arrangements, rolled. The bus system, having conceded, continued.

In 1965-70, an alliance of the Mexican-led National Farm Workers Association and the Filipino-led Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee cast anathema on the fruit of the vine in order to make agribusiness recognize the union’s collective bargaining rights. For lovers of grapes, there was a sacrifice but also a glow. What you lost in the taste of grapes you gained in the sweetness of virtue. When the boycott ended, you ate grapes again. (They tasted better than ever.)

In 1976-79, the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union organized a boycott of J. P. Stevens. The textile company had been systematically denying workers’ rights, violating laws with impunity. New York Lt. Gov.-elect Mario Cuomo urged Americans “to shun the products of J. P. Stevens as you would shun the fruit of an unholy tree.” The movie Norma Rae celebrated striking workers and organizers. In the end, the company signed an agreement with the union.

Those were reform boycotts. They harnessed anger into specific improvements on the ground. The cause was just and the means fit the ends. In the case of grapes, the premise was that the workers who harvested the grapes were entitled to collective recognition to improve their condition. Unstated but assumed was that the owners of the vines (“growers,” they were conventionally called, though their hands did not touch the vines) had the right to continue to own them. The boycott ended when the owners recognized the union. The owners still owned the vines. There remained two parties to continuing disputes, which, if you were a militant, you might call “the class struggle,” and if you were not, you might call “labor-management relations.”

Divestment is another way to vote with your money. The movement to make universities (and pension funds, etc.) divest from corporations involved in apartheid South Africa, from the 1970s through the 1980s, had a more radical objective: to force an end to apartheid by making it economically untenable. I was involved in that movement twice over, as a professor, in the University of California Faculty for Full Divestment, and as an engaged alumnus of Harvard. No one in the American movement ever proposed to blacklist South African professors. (There were exceptions in Britain although, unlike divestment, without any effect.) The objective was to further the creation of a unitary, nonracial, democratic state in which, perforce, black, “colored,” and “Asian” Africans would greatly predominate and racial inequality would no longer be legal. It was not to drive the whites into the sea, or back to Holland or Great Britain. In a fine book, Loosing the Bonds, Robert K. Massie rigorously examines South African divestment and sanctions campaigns in the United States and makes a convincing case for their effects in undermining apartheid.

Presently, I’m involved in the alumni wing of Divest Harvard, a student-run campaign to press the university to sell holdings in fossil fuel corporations whose business model is to make civilization untenable by burning carbon and dumping the by-products into the atmosphere. (So, I want to add, is Robert K. Massie.) There are several hundred other university campaigns of this sort, with some colleges, churches, cities, and foundations following suit. The objective is to stigmatize those corporations and to further the development of energy sources that the earth can sustain.

All these movements have been tied to practical objectives, some more radical than others. Their justifications lay in a sheer disproportion of rights. The rights of the Negro passengers and the grape pickers and the Stevens workers and the South African majority were not comparable to the rights of the segregationists or the growers or the South African white minority. In a sense, the fossil fuel movement has more radical ends, since the present movement, if it had divine powers, would put fossil fuel companies out of business altogether. But in none of these cases was or is there a clash of right against right.

***

Protesters against the BDS movement during the Celebrate Israel Parade in New York. June 1, 2014. Photo by AP

There are people of good will, Arabs, Jews, whatever, who support the so-called BDS movement for boycotts and divestments against Israel, either because they think it can push Israel to make concessions to the Palestinians, or because they want to stamp their feet. (The real energy goes to academic boycotts and divestment campaigns; the “sanctions” part seems nominal.) Their passion to press the state of Israel to abandon the occupation of the West Bank, to encourage de facto the emergence of a Palestinian state that would live side-by-side with a majority-Jewish state, I devoutly share. The death toll and destruction caused by Israeli attacks on Gaza this summer only strengthen the case that Israel’s defense needs do not justify wholesale destruction and everyday victimization, even in the face of terror and aggression.

Still and all, many supporters of BDS do not understand, or have not thought through, just what they are subscribing to. Consider the 2005 BDS call by Palestinian organizations, which can be read on the official BDS website. It favors “broad boycotts” and “divestment initiatives against Israel similar to those applied to South Africa in the apartheid era.” These measures, the call goes on, “should be maintained until Israel meets its obligation to recognize the Palestinian people’s inalienable right to self-determination and fully complies with the precepts of international law by:

1. Ending its occupation and colonization of all Arab lands and dismantling the Wall;

2. Recognizing the fundamental rights of the Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality; and

3. Respecting, protecting and promoting the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in U.N. resolution 194.”

Leave aside, for now, that the BDS organizers are highly selective about the international obligations they wish to enforce at the cost of academic freedom. (They have a point when they say that all campaigns are partial and selective, though one might well marvel at their insouciance when it comes to slaughter perpetrated next door by Bashar al-Assad.) Leave aside the sleight of hand with which they claim that their boycott (actually blacklist) targets only Israeli institutions, not individuals.

But consider the slipperiness of the BDS goals. The first statement I have italicized is deliberately vague. Which “Arab lands”? According to Hamas, they include the entirety of Israel. Moreover, the phrase is coded to imply that the very existence of the state of Israel, as recognized in 1948, is what constitutes “colonization.” (If that were not so, it would suffice to say “end the occupation”—meaning the occupation that took place, and continues to take place, as a result of the 1967 war and the Jewish-Israeli settlements that continue, illegally, to expand on the West Bank.) To BDS, the original sin would seem to be the founding of the Israeli state. The language masks (however thinly) the desire of one of the parties to the horrendous Israel-Palestinian conflict that the other one disappear.

But one group’s desire that another disappear deserves no respect. As a spasmodic reaction to violence, indignity, and humiliation, it is all too human. As a political position, it is a legal and moral disaster. It is not politics, it is a tantrum—and perhaps a lethal one.

At the same time, moving to point 2, the human rights of Palestinians in Israel are surely in need of defense, and a campaign toward that end is justified. Why an Israel fending off sanctions and boycotts would be more likely to honor Palestinian rights escapes me. Where is the evidence that, as the BDS movement has gained ground, Israeli treatment of its Arab minority has improved?

As for point 3, the innocent reader will likely be unaware that U.N. resolution 194 is highly contested. One line of argument notes that 194 does not proclaim an unconditional right of return. Rather, it affirms that “the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which … should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.” Another line of argument is that 194 has been rendered obsolete by events—after all, it also calls for United Nations control of Jerusalem—and in particular that the right of return stipulated in 194 is superseded by Security Council Resolution 242 of 1967, which calls for a “just settlement of the refugee problem.” There is also the question of who, exactly, is a refugee.

I do not propose to wade into legal exegesis. My point is that the BDS call goes far beyond expressing outrage at systematic Israeli mistreatment of the Palestinians—anger for which there is ample warrant. It mobilizes that legitimate anger toward a very particular idea about how to settle relations between two peoples—by enfolding one under the dominance of another. Unlike all proposals for just settlements of the murderous ethnic wars of our time—Rwanda, former Yugoslavia, Kashmir—it demands that one of those peoples give up the state in which they predominate. In the endgame envisioned by BDS, one set of pieces is left on the board, and the other removed.

Without doubt, BDS looks like a plausible feel-good proposition for people who weary of endless bloodshed. It is not a feel-good proposition for the victims of a blacklist—the Israeli academics whose scholarly collaborations and publications and research trips to the United States BDS proposes to halt, or the scholars who are to be forbidden access to Israeli archives. BDS is not a practical proposition to raise the price Israel must pay for the Occupation: by demanding, say, that the United States cut aid to Israel that goes to sustain and enlarge the Occupation. It is not focused on unjust practices, like divestment from, or sanctions against, particular corporations that sustain the Occupation, like the three companies recently divested by a narrow vote of the Presbyterian Church. It is categorical, absolute. It knows only one set of wrongs, not another. It proclaims that there is but one story to be told of the Middle Eastern tragedy, and it is theirs.

This is not politics. It is a gesture of disgust, a paroxysm of rage. Like Hamas’ rockets, it makes Israelis feel embittered and embattled. It hardens Israel’s will to listen to no one. Who benefits from such an outcome? As Noam Chomsky, who cannot be accused of tenderness toward the Jewish state, has argued, it’s not the Palestinians. And not the Israeli left either. As the Tel Aviv University historian Michael Zakim recently wrote, the Israel boycott undertaken by the American Studies Association

h

as achieved pointed success in crippling the quality of the only American-studies program in Israel, both for faculty and students. … In deepening the sense of beleaguerment among Israeli academics, the ASA finds itself in bed with a sordid group of political allies determined to delegitimize the humanism and internationalism which predominate on Israeli campuses. This campaign is part of an organized effort to isolate the Israeli left and prevent it from forging alliances with Palestinians and the Arab world.

Only the advocates of endless bloodshed grin.

But history is always surprising and sometimes pleasantly so. So let me close with some more bad news and then a touch of good news. The bad news is that, in a time of severe fiscal pressures on higher education, of plutocratically enforced inequality, and of relentless, potentially catastrophic climate change, the Doctoral Student Council of the City University of New York took time to consider not a proposal to divest from fossil fuel corporations or a campaign to boost funding but a BDS resolution against… Israel. The good news is that, this past Friday, Oct. 24, the BDS resolution failed.

Todd Gitlin is professor of journalism and sociology and chairs the Ph.D. programme in Communications at Columbia University. He is the author, with Liel Leibovitz, of The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election, and the recently published Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street. He is a Founding Member of the AAC.

Notes and links

*AMCHA

Spying by Zionist group “stifles” academic debate, say Jewish Studies scholars