Pakistan and Israel, ideological twins

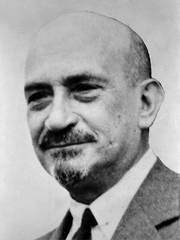

Founding ideologues, from L., Chaim Weizmann, the man who secured the Balfour Declaration and became first president of Israel; David Ben Gurion, first prime minister Israel, Muhammad Ali Jinnah first Governor-General of an independent Pakistan.

Established just a year before the State of Israel, Pakistan’s founders were well aware of the parallels between themselves and the Zionists.

By Simon J. Rabinovitch, Ha’aretz

October 01, 2013

Review: “Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea”

By Faisal Devji, Harvard University Press, 275 pp., $21.95

It may surprise readers, as it did me, that in 1981, the president of Pakistan, General Zia ul-Haq, made the following observation in an interview with The Economist: “Pakistan is, like Israel, an ideological state. Take out Judaism from Israel and it will fall like a house of cards. Take Islam out of Pakistan and make it a secular state; it would collapse.”

Zia’s message about the necessity of Islam to Pakistan is less surprising than his choice of comparison. Why did Zia choose Israel, a state to which Pakistan was, and is, implacably hostile, rather than another Muslim state? As it turns out, Muslim intellectuals on the Indian subcontinent before and after the creation of Pakistan often considered the parallels between Indian Muslims and the Jews in Europe, between Muslim and Jewish nationalism, and between Pakistan and Israel.

There are some obvious superficial similarities between the way in which Pakistan and Israel came into existence. The two states, created just a year apart, came into being through partitions that seemed at the time to be post-war Britain’s easiest route to decolonization. In “Muslim Zion,” Faisal Devji argues that it is not merely the circumstances of their birth that make Pakistan (established in August 1947) and Israel comparable states, but the very ideas behind their creation render them, in Devji’s words, ideological twins.

The most striking similarity between Zionism and Muslim nationalism in South Asia is how both melded the national and religious elements of existing communal identities to build secular political movements. Both movements were led by a new, university- or self-educated political class whose key figures were irreligious and deeply influenced by European political philosophy. Devji’s description of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the London-educated lawyer who is revered as the founding father of Pakistan, as someone whose “views of the community he sought to lead indicated a notion of representation not premised upon his identification with them,” might easily describe not just Theodor Herzl (a comparison Devji makes elsewhere in this book), but most of early Zionism’s important ideological figures. Both movements carried the imprint of the Enlightenment, seeking to replace what was perceived to be clannish and irrational religious communalism with a secular sense of belonging to a people, a nation and a homeland. The rhetoric of self-determination also influenced both movements, as Jews and Muslims came to understand the dangers of statelessness in a world organized in national political terms. As a result, both Zionists in Europe and Muslim nationalists in South Asia urged their followers to leave their homes and build a new destiny for their people elsewhere.

Some Muslims in India even believed their legal status was as precarious as that of European Jews. The Aga Khan, the first president of the Muslim League (the political movement most responsible for Pakistan’s founding), openly worried in the 1930s that, with British influence waning and Hindu nationalism rising, Indian Muslims risked falling to the position of German Jewry under Nazi rule.

Devji, a historian of South Asia at the University of Oxford, is intentionally courting controversy by claiming that Pakistan, as a political idea, is a “Muslim Zion,” and his purpose is presumably to get people to read a book about the origins of Pakistan that emphasizes the universalized modern Islam in the country’s political roots. Pakistan and Israel are “twins,” according to Devji, because, “despite the profuse use of the word homeland in both countries, as well as the glorification of their territorial and cultural integrity, no homelands can be more attenuated than these, based as they are on a national will the greater part of whose history lies outside their borders.” He argues similarly that both movements required a conscious rejection of history, geography and demographics, as well as paranoia about being an embattled minority.

In the Jewish case, the politics of paranoia, it need not need be pointed out, was not paranoid. That aside, on the one hand, Devji is correct that many Zionists indeed rejected their history in exile and their status as a minority in the Diaspora. But on the other hand, Zionism also involved a deep engagement with, and re-appropriation of, Israel’s ancient history, geography and even demographics. And unlike Pakistan, the geography of the modern Jewish state coincides with key sites of Jewish historical and religious significance, and most important, the memory, however distant in the past, of political sovereignty.

If instead of Pakistan, South Asian Muslims had proposed to end their minority status in India by moving en masse to the Arabian Peninsula and establishing a secular-democratic state surrounding Mecca and Medina based on the universal elements in Islam, could anyone credibly call the geography accidental or attenuated? The answer is no, and as Devji suggests, Muslim intellectuals in South Asia had to create a “pure” nationality decoupled from geography precisely because of the location of their new homeland and its distance from Mecca. They also had to give their homeland new religious significance. In fact, in another forthcoming book on Pakistan’s origins, Venkat Dhulipala argues that religious Muslims – not just the secular intellectuals – supported the creation of Pakistan because they saw the potential for a Muslim state in South Asia to become a new sacred place, or specifically a “New Medina.”

For all of the surface similarities, the ideas that lay behind Israel and Pakistan are different enough for the claim to ideological twinship to look shaky on closer inspection. Devji intends for the comparison to highlight misconceptions about what lies at the root of Muslim nationalism in South Asia historically and the role of fundamentalist Islam in Pakistan today. In order to serve as a better corrective, however, his book would have benefited from a comparison based on a firmer familiarity on the author’s part with Zionism and Israel. Unfortunately, what is clearly Devji’s very limited knowledge of these topics is based primarily on the writings of Hannah Arendt, Theodor Herzl and the current-day critic of Zionism Jacqueline Rose, and this results in a picture of the Jewish national movement that is narrowly, and inaccurately, focused on its political aspects.

Contrary to Devji’s perception, the Zionist movement before 1948 was not monolithic and was not always and at all times focused on the politics of creating a state. Zionists of different stripes emphasized spiritual, cultural and religious renewal, or Jewish socialism as Zionism’s primary purpose.

Pakistan may have created a nation practically out of thin air, based on a shared sense of belonging, paranoid politics and newly felt desire for self-determination, but Israel did not. The choice of the Land of Israel as the site of the modern Jewish national project was not accidental at all, and while it is true that other options were considered at different times, within a decade of the First Zionist Congress, it became clear to most Zionists that in order to be tenable, the new national project could only be directed to Israel (at that time Ottoman Palestine), precisely because it was already invested with spiritual and historic significance. The same might be said about vernacular Hebrew. Zionists of different stripes considered other languages as possible national languages, and the movement was naturally polyglot, but it was the Jewish Diaspora’s linguistic diversity that necessitated a lingua franca, and Hebrew was the common thread.

Before we throw the baby out with the bathwater, it’s important to point out that this book is not principally about Israel or Zionism, it is about Pakistan. And as much as Devji’s understanding of Muslim nationalism would have been sharper had he probed more deeply and comparatively into the varieties of Jewish nationalism in Europe, his book is still fascinating in focusing on a number of ways that Muslim thinkers thought about the Jews when constructing a secular Muslim nationalism intended to adapt their collectivity to the modern world.

Devji demonstrates a widespread interest among Muslim intellectuals in comparing themselves to, and learning from, the experience of Diaspora Jews. One fascinating example is the poetry of Muhammad Iqbal, who like Jinnah, was a London-trained lawyer and a literary and political figure seen as a founding father of Pakistan. In “Mysteries of Selflessness,” a long Persian poem Iqbal wrote in 1918, and quoted by Devji, he ascribed Jews’ perseverance in the Diaspora to their ability to maintain the memory of their ancestors amid persecution and dispersion. Iqbal suggested Muslims “take warning” from the Jews:

Their furrowed brow sore smitten on the stones

Of porticoes a hundred. Though heaven’s grip

Hath pressed and squeezed their grape, the memory

Of Moses and of Aaron liveth yet;

And though their ardent song hath lost its flame,

Still palpitates the breath within their breast.

For when the fabric of their nationhood

Was rent asunder, still they labored on

To keep the highroad of their forefathers.

Iqbal primarily sought to convey to Muslims a lesson about the dangers that acculturation and secularization posed to the religious bonds at the core of nationhood. He proposed that for Muslims in India, territorial autonomy would provide the economic and political empowerment they needed in order to adapt Islam to modernity, before they lost control. Though Devji seems unaware, this principle – adaptation to the challenges of modernity – is if anything the fulcrum bridging the Jewish enlightenment to not just Zionism, but all forms of Jewish nationalism. To Iqbal, the lesson offered by Jews in the Diaspora was not simply that they preserved the memory of their ancestors and their nationhood in the midst of persecution, but that those modern Jews who sought to do away with religion opened the door to greater suffering.

Take heed once again,

Enlightened Muslim, by the tragic fate

Of Moses’ people, who, when they gave up

Their focus from their grasp, the thread was snapped

That bound their congregation each to each.

Iqbal is a fascinating figure whose position in the Pakistani national narrative seems akin to Hayim Nachman Bialik’s in Israel’s. Like Bialik, Iqbal participated in the politics of his national movement, while questioning its aims. Like Bialik, Iqbal composed poetry in multiple languages that grappled with how his people and nationality could survive secularization and the modern world. Iqbal is sometimes called Pakistan’s “national poet,” and Bialik Israel’s, though neither lived to see those states created.

Iqbal believed in a Muslim nationality focused on the universal elements of Muslim religion and culture. According to Devji, even the adoption by Indian Muslim intellectuals of the proper name, Islam, to describe the totality of Muslim civilization reflected a very intentional ecumenism shared by Iqbal and Jinnah. National Islam – the Islam of the Muslim homeland – had to transcend, and even level, the differences between the multiple Muslim branches and sects in South Asia. And while Devji doesn’t make the connection, the idea that Pakistan might be an example to Muslims everywhere of the universal elements of Islam as a civilization does look very much like the intellectual genesis of many kinds of Zionism (Bialik’s and Ahad Ha’am’s in particular).

Devji sees a sort of Protestant Islam in Iqbal and Jinnah’s theologies that made belief a personal matter and relegated to God, not man, and certainly not the state, the responsibility to sort the virtuous from the heretic. His intention is to show how far Pakistan’s blasphemy laws in particular, and its laws regulating belief and practice in general, stray from the origins of Muslim politics in Pakistan and the beliefs held by the country’s national heroes.

A common theme of the Israeli and Pakistani elections held earlier this year was the emergence of a youthful (but not young) celebrity candidate – Yair Lapid in Israel, Imran Khan in Pakistan – who promised to shake up the political landscape and looked set to play the role of kingmaker in a new government. Yet this similarity, on closer inspection, is again coincidental when one considers that Pakistanis celebrated in this election the country’s first peaceful transition of power under parliamentary rule, while Israelis tend to bemoan the frequency of this occurrence.

In the same vein, if Devji has a contemporary agenda in shining a light on Pakistan’s origins by comparing it to Israel’s, he would have been much better off engaging in real comparison. There are similarities here, but these are not carbon copies, or ideological twins, and it is their differences that tell us why the two states look so distinct some 60 years after their founding.

Some of Devji’s more acute insights suggest that this might have been a worthwhile undertaking. He pinpoints, for example, the problem that Israel and Pakistan share as states that define themselves as Jewish and Muslim in a secular-national sense, but using religious terms: What powers must the state cede to the nation or a religious authority if defining who is a Jew or a Muslim also determines who qualifies for citizenship? This is a problem Israel has yet to solve, but if Devji had looked more seriously at the ideological diversity within Zionism, he might have intuited more answers as to why Israel, whatever its problems, has stable democratic and legal institutions that are still working to negotiate its answer.

Simon J. Rabinovitch is an assistant professor of history at Boston University.