Imperial intervention – or duty to protect?

The three OD contributors are Michael Ignatieff, David Petrasek and Lorena Ruano

Syrian refugees gather at Zaatari camp near the Syrian border, near Mafraq, Jordan July 26, 2013. The UN is the principle body to care for the victims of conflict. Photo by Raad Adayleh/AP.

The Duty to Protect, Still Urgent

By Michael Ignatieff, NY Times/International Herald Tribune

September 13/16, 2013

TORONTO — PRESIDENT OBAMA’S failure to get Congress to support airstrikes in Syria, coupled with the vote against military action in the British House of Commons, brings home a key fact about international politics: when given a choice, democratic peoples are reluctant to authorize their leaders to use force to protect civilians in countries far away.

In 2001, the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, on which I served, developed the idea that all states, but especially democracies, have a “responsibility to protect” civilians when they are threatened with mass killing. For those of us who have worked hard to promote this concept, it’s obvious that our idea is facing a crisis of democratic legitimacy.

Let’s be clear what the problem is: it’s not just compassion fatigue, isolationism or disengagement from the world. It’s more than war weariness or sorrow at the human and financial cost of intervention. It goes beyond disillusion at the failures to build stability in Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya.

The core problem is public anger at the manipulation of consent: disillusion with the way in which leaders and policy elites have used moral and humanitarian arguments to extract popular support for the use of force in Iraq and Libya, and then conducted those interventions in ways that betrayed their lack of true commitment to those principles. To quote the Who, the people are saying they “won’t get fooled again.”

Rebuilding popular democratic support for the idea of our duty to protect civilians, when no one else can or will, is a critical challenge in the years ahead.

The first step is to re-emphasize that protecting civilians is about preventing harm, not primarily using force. The public knows an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It has no major problem with conflict resolution, foreign assistance, law and order training, or any of the other elements of prevention.

The real challenge comes when prevention fails, when force becomes the last resort. Here the public’s problem is mission creep, the way protection of civilians morphs into regime change. Many people who were prepared to stop Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s slaughtering of civilians in Benghazi grew increasingly uneasy when that mandate was used to bomb Tripoli. We need to make sure that the military puts civilian protection first and last as its sole legitimate purpose.

The third challenge, most difficult of all, is how to protect civilians when the Security Council blocks the use of force. For all the talk about American exceptionalism, the American people don’t like using force if the United Nations is against it, and they are uneasy if allies won’t stand with them.

The reality, however, is that if the United States wants to stop atrocity crimes, it may have to go it alone. With Syria, the United States’ threat of force has played a role in the diplomatic breakthrough involving Russia that just might protect civilians against further use of chemical weapons. If there are rare cases like this where the threat of force may be “illegal but legitimate” (as an international commission on Kosovo called the NATO bombing), the American people want to know how to keep the use of force from getting out of control.

This is why President Obama’s decision — and Prime Minister David Cameron’s, too — to seek democratic authorization for the use of force was the right way to go, even though it hasn’t turned out the way they wanted.

As they’ve both discovered, when you go to your legislature for authorization, there is a price to pay. When democracy becomes the venue for testing the legitimacy of force, the bar of justification is set high. Democratic legitimacy is not a substitute for international legality, but it performs one of the crucial functions of law, which is to subject the use of force to strict control.

Democratic consent, of course, can be manipulated, as it was over Iraq in 2003. But when it is, democratic peoples have learned from the experience and have raised the bar higher.

Their reluctance to use force is not a passing phenomenon. Immanuel Kant was right that when the people bear the cost of war and get a chance to tell their leaders what they think, they are reluctant to authorize it.

Still, it is critical that they be willing, in the right circumstances, to do so. In the future, the Security Council may be deadlocked about intervening, and presidents and prime ministers will have to turn instead to their people for permission to save civilians. If the case for action is made honestly, if no one’s consent is manipulated, let’s hope the people say yes. We can’t fight genocide, ethnic cleansing and chemical weapons attacks unless they do.

Michael Ignatieff is a professor at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard and at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto.

Yarmouk camp for Palestinian refugees in south Damascus, Syria, Many refugees have been killed both in fighting within the camp and shelling of the camp by the Assad regime. The AlRay agency reports that more than half of the 530,000 Palestinian refugees registered in Syria have now been displaced and 15 percent have fled abroad, including 60,000 to neighbouring Lebanon and over 7,000 to Jordan. Photo by AP.

R2P – hindrance not a help in the Syrian crisis

By David Petrasek, Open Democracy

September 13, 2013

The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine has failed to build an international consensus for action to protect civilians in Syria. Worse, R2P’s implicit support for military action without UN authorization has contributed to the UN’s paralysis.

The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine was developed to forge consensus in favour of international action to prevent or stop mass atrocities. It has failed to do so in Syria. But worse, the doctrine’s implicit support for intervention without UN authorization has contributed to the paralysis of the international community to respond effectively to the human rights crisis in Syria. Re-building an international consensus to act against atrocity will require re-thinking R2P and the illusory military solutions it offers.

A familiar debate

Time’s caption to a series of photos on Nato’s 1999 intervention in Kosovo was: “Madeline’s war, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright helped push the U.S. into Kosovo as part of the assertive, moralistic new world role she’s urging for America. Here’s a look behind the scenes as she struggles to make it work.” Compare and contrast with Air War in Kosovo Seen as Precedent in Possible Response to Syria Chemical Attack,NY Times, Aug. 23rd 2013.

The International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS), which first proposed R2P, argued that UN Member States had a responsibility to act to prevent atrocity, and presented a framework to guide discussions on how to do so collectively and effectively. The aim was to change the terms of the ‘old’ debate on humanitarian intervention, which was prominent in the run-up to NATO’s intervention in Kosovo. That debate was characterized by assertions of a right of unilateral action, and it mixed humanitarian motives for intervention with other broader strategic and security goals.

Regarding Syria, however, R2P has changed little. It is not just that no effective action has been taken to halt the ongoing atrocities, but the terms of the debate on a possible military intervention are eerily reminiscent of the 1990s. The UK Government issued a legal justification for military action citing the “doctrine of humanitarian intervention”, and more or less echoing earlier arguments to justify the NATO action in Kosovo. Similarly, neither President Obama nor senior US officials have framed their case for military strikes within the R2P framework, which requires that the goal of protecting civilian lives must be the primary purpose of any R2P-justified intervention. Rather their argument is grounded primarily in the notion of a punitive strike to deter Syria or any other state from using weapons of mass destruction. This might benefit the civilians who will suffer if these weapons are used again. But as President Obama made clear in his speech on 10 September, it is also intended to send a message to Iran and others who might acquire or use weapons of mass destruction—a message grounded primarily in strategic, not humanitarian concerns. Just as maintaining NATO’s credibility ultimately pushed the alliance to war in Kosovo, a similar concern, over US credibility will be prominent if the US attacks Syria.

A Palestinian in a Syrian refugee camp. Photo from UNHCR

R2P’s slippery slope

If R2P is little help in solving Syria’s crisis, it is also proving a hindrance. The possibility of a military intervention in Syria without UN authorization—raised early on by many western officials—has hardened opposition to other UN measures and undermined unified support for a mediated solution to the conflict, the only option that might end it in the short term.

As endorsed by UN Member States in 2005, R2P requires that states willing to intervene gain Security Council approval, as NATO did in Bosnia in 1994-95 and in Libya in 2011. But a bolder version of R2P asserts the legality of intervention to halt atrocity even without Security Council approval. The ICISS proposal in 2001 required Security Council authorization, but it left open the possibility that there might be cases when interventions would be “legitimate” even without UN authorization. This is the argument used by many to justify NATO’s air attack in Kosovo in 1999.

Given Russian support at the UN for the Assad regime, it is this bolder version of R2P, and the Kosovo precedent for applying it, that is called on in support of arguments for the legitimacy of military action in Syria. Such arguments were being raised already in 2012 (by, among others, the UK Foreign Secretary). The US and its allies—though until recently wary of using force—nevertheless asserted their right to do so if blocked in the Security Council. (This was implicit in the “red lines” set by President Obama in 2012.) Further, the sense that the US and its allies might circumvent the Council was strengthened when Russia, Brazil, South Africa and others expressed concern that the UN-authorized NATO operation in Libya was misused to effect regime change.

In short, the threat of a resort to force outside UN control has hung over the Syrian crisis almost from the start. And arguably, this has made it much more difficult to win Russian and Chinese approval for other measures. For example, the Security Council could refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court, or impose arm embargoes or targeted financial, travel and other sanctions against members of the Assad regime. The only sanctions taken to date against Syria have been imposed by regional bodies or states acting alone, but are not universal in scope. Indeed, the Security Council has taken almost no action on Syria. Perhaps no other civil war in the past two decades of similar intensity and lethality has been so neglected by the Security Council.

Russia’s near-criminal support for the Assad regime is part of the explanation, of course. But it cannot be the whole explanation. In the Bosnian conflict, Russian support for the Serbian position was also pronounced, yet this did not prevent Russia from endorsing UN action to establish an international criminal tribunal, to create a no-fly zone and, eventually, to authorize NATO air strikes against Serb positions that were targeting civilians. None of this was sufficient to prevent continued massacres, including at Srebrenica, but the fact is that the UN’s record of action in Bosnia compares favorably to its record so far in Syria.

Perhaps Putin’s newly assertive Russia is less willing to join in a Western consensus for action. Coupled with China’s devotion to non-interference in internal affairs, this might be enough to block any kind of action to protect human rights in Syria. Yet if either or both explanations were true, how to explain both countries’ willingness to endorse—or at least not block—Security Council support for the French intervention in Cote d’Ivoire in 2011 or Mali in 2012, or the referral of the Sudan and Libya to the ICC, or indeed the NATO action in Libya, or other cases in recent years where the Security Council has used its enforcement powers to protect civilians? Perhaps it is simply that defending the Assad regime is uniquely important to the Russians. But if so, how to explain the position of the Chinese, who have few close ties to the regime? It is fair to conclude that opposition to Security Council action in Syria is partially based in the fear that strongly worded resolutions not endorsing military action may nevertheless be used to justify it—an outcome all too familiar from previous debates (for example, over Iraq in 2003 or over Kosovo in 1999).

The utility of force

Yet if military force could halt the atrocities and enforce a ceasefire, why should we be overly concerned about Russian and Chinese sensitivities? The answer is that military action on the terms being discussed—including no-fly zones, protected havens, or targeted ‘stand-off’ air and missile strikes—offers little hope of effectively protecting Syrian civilians. This is especially so given that the action proposed is de-linked from any political solution or negotiation process.

Those who disagree point to NATO’s air war in Kosovo in 1999, but that offers conflicting lessons. The overwhelming majority of civilian deaths in Kosovo, and the great majority of ethnic cleansing, happened after NATO had begun its air campaign. By limiting itself to an air war, NATO was unable to protect civilians on the ground from reprisals and expulsion, even if it could limit the Serbian army’s ability to use heavy weaponry against them. But at least in Kosovo the bombing was linked to a clear set of proposals for a political solution, so that President Milosevic understood the terms on which it might end. (These did not include his departure from office; he remained in power for another year until he lost elections.)

Rebels in Libya running from government air-strikes. Photo by Yuri Kozyrev /Noor for Times

Some might argue that making clear to Assad from the start that the Russian veto wouldn’t necessarily provide immunity from military action was important to provide a credible deterrent against further atrocity. But the evidence that it has done so is lacking; arguably, civilian deaths have risen even as the military option has gained attention. President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry argue that the credible threat of military action has pushed Assad to negotiate the surrender of his chemical weapons. They might be right, but it is not clear that a threat framed more broadly(i.e. against attacking civilians), would achieve similar results, nor has the US indicated its readiness to make such a threat.

The fact is that coercive military interventions are rarely an appropriate response to prevent mass atrocities. This is especially so when they do not enjoy the support of key actors, including neighbouring states. Sometimes they will be necessary and feasible—as clearly was the case in Rwanda. But the fact that a military intervention would almost certainly have been the best option to halt the genocide in Rwanda obscures the fact that since Rwanda there have been so few other situations (and none on the same scale) where the same is true. This is especially the case, as in Syria, where the military action is not part of a broader strategy to achieve a ceasefire and a return to negotiations (and indeed, if done unilaterally, will only make this more difficult).

The scale of the crisis in Syria demands action, but airstrikes and no-fly zones, unilaterally imposed and directed at only one side in the conflict, are unlikely to effectively protect civilians. The fact that the R2P doctrine nevertheless fuels support for such an outcome, to the detriment of other measures, means it needs re-thinking.

Re-thinking R2P

R2P proponents are unlikely to agree, arguing that R2P is much more than a doctrine for military intervention. Rather, as they see it, the use of force is a last resort; R2P’s purpose is to spur any international action that aims to prevent or put an end to mass atrocity. Thus, the mediation that put a stop to the post-election violence in Kenya in 1998, the referral of the situation in Libya or Sudan to the ICC, the holding of crisis sessions by the UN Human Rights Council, and even the deployment of peacekeepers at the invitation of the conflict parties: all these and more are cited as evidence of the R2P doctrine at work.

But it is unwise to bundle together with R2P’s military doctrine a range of lesser (though not necessarily less effective) measures. It may have the perverse effect, as in the Syria case, of tainting all enforcement measures with the controversy attached to military intervention, especially in its bolder (non-UN authorized) version. Further, these other measures are not dependent on the R2P doctrine. They were used, sometimes to great effect, before any notion of R2P was elaborated. Most importantly, many of these mechanisms have a solid basis in international treaties that is much firmer than the political basis for R2P.

At its core, R2P is about building the greatest possible consensus for international action to prevent or halt mass atrocity. As long as the doctrine, and many of its proponents, remain fixated on the possibility of military action outside UN control, R2P is likely to hamper, not hasten, the moment when such a consensus is certain.

David Petrasek is Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa. He was formerly Senior Policy Director and Special Adviser to the Secretary-General of Amnesty International. David has worked on human rights and conflict resolution issues with the UN, foundations and NGOs for over 25 years.

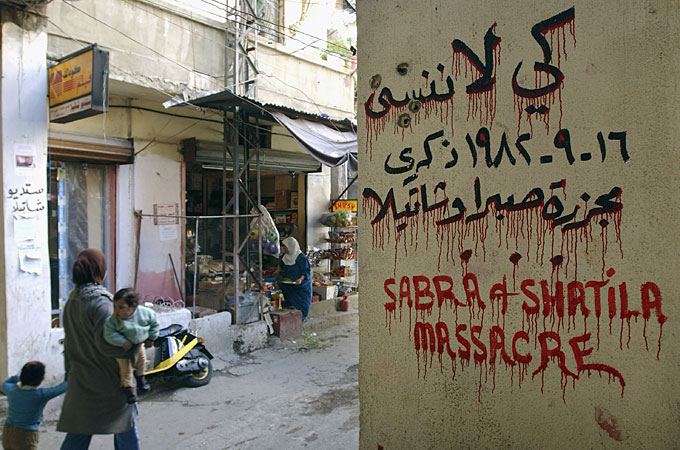

No duty to protect: A Palestinian refugee in Beirut passing a reminder of the 1982 massacre of several thousand Palestinian refugees in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. The slaughter was carried out by the Lebanese Phalanges, a Christian militia, after a multi-national force had withdrawn and while the camps were surrounded by the IDF under the control of Ariel Sharon. It lasted 16th-18th September.

Pity the people of Syria- and the principle of R2P

By Lorena Ruano, Open Democracy (Global Rights)

September 16, 2013

Though postponed, the US still threatens to attack Syria to punish the Assad government for the use of chemical weapons. But it would be illegal, and ineffective – helping neither the people of Syria, nor the principles of Responsibility to Protect (R2P).

Pity the people of Syria, for there is no end in sight to their suffering, caught as they are between a brutal dictator and a myriad of rebel groups; and between the interests of outside great powers and the interference of their neighbors. Pity the R2P doctrine as well, for this sad case is undermining its flimsy status establishment as a widely recognized principle of international law. In this piece I argue that the proposed attack by the US and France to punish the Assad government for the use of chemical weapons would not be legitimate, nor would it be legal, and it would be ineffective. It might help neither the people of Syria, nor the principles of R2P.

First, I would challenge Gareth Evans*: there is no “universal consensus about the basic principles” of R2P as he asserts. The statement that “no state now disagrees that every state has the responsibility” to protect its own people is far from reality. This might be the case for democratic states, where governments are supposed to answer to their peoples, but it is not at all clear that it applies in authoritarian ones, where the raison d’état tramples human rights. In Latin America, having lived through dictatorships, we know this all too well.

Unfortunately, the idea that human rights should be put before the preservation of the state is actually not as widespread as the decade of the 1990s, of liberal hegemony, led us to believe. When faced with internal insurrection and a real threat to their integrity, many more states than we would like to admit are ready to use force against their own unarmed population; to use torture, murder, and to commit other severe violations of human rights. Once states resort to the use of force, the line between mere killing and an atrocity is a very thin one indeed. Russia and China, both permanent members of the Security Council, seem to be quite sympathetic to the Assad regime in that sense. And I am afraid that they are not alone in the international system. The Mexican government for instance, along with many others in Latin America, embraces a mildly non-interventionist position, caught between a tradition of defending national sovereignty and a newly acquired activism on human rights that rejects an authoritarian past.

Second, as Kwesi Aning and Frank Okyere point out, the application of the concept of R2P becomes all the more difficult in a situation of a messy civil war, as is the case of Syria, where it is difficult to establish who is committing what war crime. In Syria, all the warring factions seem to be committing gross violations of human rights, and few independent observers and journalists are allowed in to the country. The truth is we do not know for sure who is nastier, and we cannot always identify the perpetrator. In this context, the punishment of just one warring faction (the one we like the least – and not the others) amounts to intervention in a war to help those we dislike the least. In other words, if the principle is not applied evenly and impartially, R2P becomes a mere pretext to help allies and undermine enemies. Moreover, if the punished faction happens to be the government, as happened in Libya, intervention may lead to regime change. If applied in this way, the legitimacy of the principle of R2P is inevitably eroded, as the other authors have underlined.

Third, because the Syrian case involves a messy civil war, we enter the terrain not only of R2P, but also of the laws of war and the prohibition to use chemical weapons. It has to be acknowledged that the whole notion of the jus in bello remains somehow perplexing in the modern era, as it rests on the assumption that, in the context of war, some forms of killing are more morally acceptable than others. That was understandable in the age of chivalry and up to the WWI, before modern weaponry was developed and war was waged on a defined battlefield, more or less exclusively by soldiers. The motive behind banning chemical weapons or other weapons of mass destruction (WMD) is that they kill indiscriminately; they don’t distinguish between civilians and soldiers, and belongs to this “idealized” conception of war. However, in “the era of total war” (as Hobsbawm called it), and when violence is not waged by regular armies but by a myriad of different types of fighters, and in the midst of cities and villages, the effect of WMD is not very different from what happens when heavy artillery is used to bombard an urban area.

Why does the use of chemical weapons constitute a ‘red line’, while other equally horrific war crimes (torture, massacres) do not? Many of these questions remain unanswered in principle. In practice and in this case, the answer is that the US President set that ‘red line’, and now that the use of chemical weapons has been established, his credibility is at stake. The decision to strike Syria might be justified by the US national interest, and to maintain the credibility of US commitments to their allies, particularly Turkey and Israel, but its justification on the basis of R2P is slipping further away. If there is a military strike against Syria, most people will see it as a result of old-fashioned realpolitik, rather than a heroic application of R2P’s moral principles. And that will seriously undermine support for R2P.

For these three reasons, it is possible to conclude that the R2P doctrine is not nearly so widely supported in the international society as some of us hoped it would be. That is why the legitimacy of a military intervention in Syria is widely questioned today by many states, parliaments (as in the UK) and public opinion (as in the US).

Beyond legitimacy and morality, comes the problem of legality. Without a Security Council resolution under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, the use of force is not legal, even to enforce R2P, or to stop genocide, or for whatever reason. The ends do not justify the means. Even if it is legitimate (as was the case of Kosovo, but is questionable in Syria) to attack the Assad government, without a UNSC mandate it would be illegal, just as NATO’s Kosovo intervention was illegal. As Prof. Chimni correctly points out, one unlawful intervention does not legalize another. The contradiction is plain to see: a violation of a principle of international law cannot be punished through violating another principle of international law. It is difficult to see how this kind of praxis would help in winning wider acceptance of R2P norms, or wider respect for the rule of law in the international society. Kosovo was an anomaly: there was a flagrant attempt to commit genocide by a dictator no one liked. He did not succeed because NATO’s intervention prevented it and his Russian friends were too weak. The distribution of power has changed a lot since 1999, and Bashar Al Assad has many more friends in powerful places than Milosevic did.

And finally there is the very practical issue of what a military attack, even if it was legitimate and legal, could achieve in the Syrian situation. How can military strikes stop the use of chemical weapons? The proposed intervention amounts to mere punishment, but will not solve the ongoing tragedy. Making a difference to the victims would require very costly and long term commitment. However, the precedents of interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan loom large – they were not able to stop the carnage even with troops on the ground for many years.

Many have pointed out that any military action will create more victims, more ‘collateral damage’. Bombing Belgrade from 10,000 feet to defend Kosovars was not a clean affair either – remember the strikes on the Chinese embassy. And in the case of Syria, undermining the government in Damascus might embolden Islamist extremists. Bombing from 10,000 feet will not stop the war, or the suffering, or the tragedy. It might very well make it worse and further internationalize the conflict.

Regardless of whether an attack is launched to punish the use of chemical weapons, if the humanitarian concern for the Syrian people is genuine, Western governments could do much more to mobilize the international community to attend to the unfolding disaster of refugees and internally displaced people that this carnage is producing. That would be widely legitimate, certainly legal, and would offer protection to millions of innocent civilians who need it.

* R2P down but not out after Libya and Syria, Gareth Evans, Open Democracy, 9th September, 2013