For the occupation, against the occupation, or cowardice

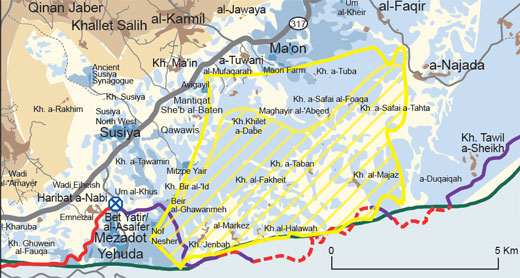

Firing zone 918 (in yellow). Map from B’Tselem

A lesson in cowardice at the IDF’s firing zone 918

High Court justices show critics are right to accuse them of failing to address military dictatorship to which Palestinians are subjected.

By Amira Hass, Ha’aretz

September 09, 2013 |

The Israeli poet Haim Gouri walked out of the church-like hall even before the hearing for which he had come last Monday began. Instead of a crucified Jesus, this wall was decorated with a menorah, the symbol of the State of Israel.

On the elevated platform sat High Court of Justice President Asher Grunis and Justices Hanan Melcer and Daphne Barak-Erez. They discussed three other petitions before they began touching the hot potato of Firing Zone 918. Like Gouri, other would-be observers who got there at 11:30 A.M., when the hearing was supposed to begin, left before it actually began two and a half hours later. In so doing, they missed out on learning the lesson in cowardice delivered by the judges.

The wooden benches of the quasi-cathedral were full, and the judges presumably knew that most people had come to hear their ruling on the petition against the state’s demand that 1,000 people be evacuated from their West Bank homes to allow the Israeli army to train on some 26,000 dunams of land in the southern Hebron Hills. (This is part of the 9.5 million dunams of land the army already uses as training or firing zones, 6.5 million of which are in the Negev and 1 million dunams are in the West Bank – nearly one-fifth the size of the entire territory.)

Silent and attentive Palestinians during the hearing on Firing Zone 918. Photo by Emil Salman.

In the front pew sat a few arch-inspectors from the Civil Administration. In the middle rows, wearing white kaffiyehs, were 20 of the 252 petitioners seeking to do away with the firing zone. They remained in their seats for the hours it took until their turn came: upright, silent and attentive, even though most of them don’t know Hebrew. The others were mainly Israeli activists and European diplomats.

The concept of “suffering,” or, to speak more euphemistically, the “humanitarian issue,” itself suffers from a surfeit of attention in national folklores, the media and NGOs. Ilil Amir, the attorney arguing the case on the state’s behalf, stated that she and her colleagues in the prosecutor’s office, Itzchak Barth and Aner Helman, clearly see “humanitarian difficulty in the situation that exists today.” In other words, she is saying, we’re merciful people who have not become desensitized to suffering. But “suffering” and “humanitarian difficulty” are concepts that fit neatly in the category of natural disasters, acts of God, bad luck, subjective misery; something accidental, individual, devoid of interests or intent.

A petition by 24 Israeli authors against the evacuation also makes reference to suffering. That document, by contrast, does name a direct cause for the “suffering” of the 252 High Court petitioners and their families: “During these years they have suffered unceasing abuse from the army and the settlers. Their homes have been demolished over and over, their cisterns have been blocked and their crops destroyed … They are threatened with immediate evacuation from their villages. They live like this in constant fear, helpless in the face of an unbridled power that is doing everything it can to uproot them from the place where they have lived for hundreds of years.”

The justices decided not to force the state prosecutors to address the facts or the arguments in principle that were presented by the petitioners. For instance, the court did not compel the state to address the point made by Tamar Feldman, an attorney for the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, that geologist and geographer Nathan Shalem encountered these farming and shepherding villages in the 1930s, even though the state argues that the area was a firing zone before it became the petitioners’ permanent residence. Nor did the court compel the state to address the argument that Civil Administration reports about the repeated demolition of cisterns and tents show how the people living there are attached to their homes and their land, and keep coming back there despite the persecution.

The request that the state reveal what is important enough about these 26,000 dunams of land to justify the evacuation was left hanging in the air. The justices rushed to the aid of the state prosecutors and exempted them from having to respond to the petitioners’ arguments that the state’s position contains several untruths, for instance the contention that “no damage was caused” during training exercises that took place in the area (and therefore the training exercises should be allowed to continue and the petitioners should access their land only on weekends as well as two months a year, as per the state’s suggestion).

June 26, 2013 – Writers Zeruya Shalev, Eyal Megged and Alona Kimhi and attorney Shlomo Lecker (from left to right) speak in the village of Mufaqara, south of Hebron, about Palestinians living within Firing Zone 918, who face possible military eviction. Photo by Matt Surrusco, +972 magazine.

Shlomo Lecker, the other attorney representing the petitioners, has personally filed four claims of damages from residents who were seriously injured due to firing in the area and won compensation of NIS 2 million.

“This instance is special,” Grunis said. But the thing is, that’s not the case; there are plenty of other Palestinian communities that Israel plans to evict. The only thing that’s special about this is the international tumult created by Israeli activists from rights groups like Ta’ayush, Rabbis for Human Rights, Breaking the Silence and the Association for Civil Rights in Israel. The judges proved over and over that they are afraid of the fundamental question Leker raised, and which applies not only in this case: How is it possible, after 46 years of an occupation regime, to continue to rely on military legislation that is supposed to be temporary, and use it to justify the unfathomable gap, the criminal and evil chasm between the way in which the state treats Jews and the way in which it treats Palestinians.

For the High Court to reach a conclusion on this issue means it must take a stance: to side with the army, with its dictatorial control over the Palestinians and its evacuation plan, or to oppose it. There is no middle ground.

“It’s worth thinking of creative solutions and creative paths,” said Grunis. Therefore he proposed mediation, even though an attempt at mediation failed in 2004-2005, when the state offered a measly 200 dunams of state land near the West Bank town of Yatta in exchange for the firing zone. Mediation creates the illusion that this is simply a civil dispute, a private matter about “controversial” land; under this illusion, both sides have equal power and equal resources, and any benefit or damage that could accrue will affect each side in a similar manner.

No matter what the result of the mediation is, this judicial panel has already found its own personal escape route.