Governance bill can't fix system as it ignores democratic values

This is the first of three postings on Israeli democracy, lack of. This one concentrates on the governance bill which has passed its first reading amidst much consternation.

1) i24 news: Knesset passes Governance Bill prompting allegations of racism, brief summary;

2) Yossi Mekelburg: Israeli politics in search of good governance, August 8th, analysis of Israeli political system;

3) Yitzhak Laor: Israel’s dying democracy, August 5th;

4) Ha’aretz: Yesh Atid MK ‘harshly’ sanctioned after abstaining in governability vote;

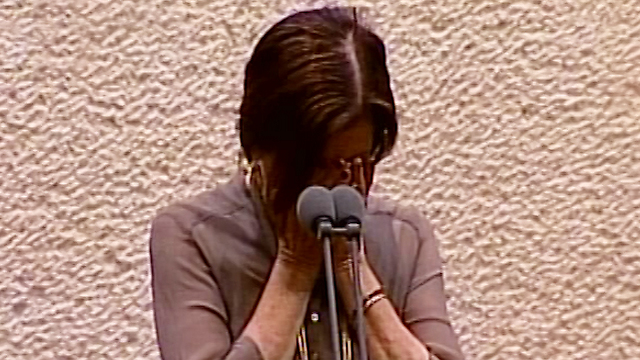

MK Zahava Gal-On (Meretz) weeps silently on Knesset podium as governance bill discussed.

Knesset passes Governance Bill prompting allegations of racism

Proposal to raise electoral threshold seen by opposition as targetting Arab parties

By i24

August 01, 2013

The Knesset on Wednesday passed the so-called Governance Bill on first reading by a majority of 63 to 46. The vote on the motion, one of whose clauses stipulates raising the electoral threshold to 4 percent, ramped up the emotions at the plenum, prompting some opposition MKs to brand the bill as discriminatory and racist.

The legislation was brought forward by MK David Rotem from the Yisrael Beitenu party as an amendment to one of Israel’s Basic Laws — which comprise Israel’s central body of legislation. It will limit the number of government ministers to 19, and of ministerial deputies to four, in addition to significantly complicating the procedures of bringing no-confidence motions to a plenum vote.

The Governance Bill’s most controversial proviso, which passed in the reading, proposes to raise the electoral threshold from two to four percent. As a result, the small parties, such as the Arab ones, may be forced to unite in advance of the next election to stand a realistic chance of being elected to the Knesset.

During the debate preceding the vote, MK Zahava Gal-On (Meretz) stood and wept silently on the podium. “This is a law to bolster racism,” Gal-On charged. She was followed by her fellow Meretz MK Nitzan Horowitz who stood silent for a minute and walked down saying the bill is “petty and pathetic.”

MK Dov Henin (Hadash ) accused the bill’s initiators of dark motives: “The aim of the bill is the political transfer of the Arab population.”

Several Arab MKs, including Ahmad Tibi (United Arab List – Ta’al) joined the silent protest. Tibi took the podium and stood with his back to the plenum. The Knesset channel

The bill must pass in two more readings in order to be ratified as law.

Israeli politics in search of good governance

By Yossi Mekelberg, Al Arabiya

August 08, 2013

Many years ago one of the most respected political science lecturers in Israel, the sorely missed Professor Gideon Doron, described the political arrangement in Israel to his class, as shifting from a nominal democracy to a minimal democracy. When one looks at the present situation in Israel, it would seem that some of the politicians from within the coalition are endeavouring to minimise Israeli democracy even further. Last week the Israeli Knesset endured one of its most difficult and surreal days in its history, as the coalition was pushing through its controversial Governance Bill just before the Knesset adjourned for its summer recess.

In a rare show of unity among the opposition, members from the Left, Arab, and Ultra-Orthodox parties took turns standing on the rostrum in silence in protest of the bill. Their main grievance was against the part of the bill which raises the entry threshold to the Israeli parliament to 4 percent.

For the supporters of this bill, mainly from within the ruling coalition, the new bill would provide the government the much needed stability in a very fragmented political environment, which in return would enable an elected government to govern. However, this sentiment was not even remotely shared by the opposition.

More power in the hands of fewer people

There is a strong sense among those who oppose this bill, that it is a governmental ploy to concentrate more power in the hands of fewer people, and a move that would harm Israeli democracy. One of the parliamentarians, Zahava Gal-On from the Meretz party, broke down in tears while speaking. She described the bill as creating a “terrible sense of tyranny” and said the bill has nothing to do with better governance. She was followed by the leader of the Labour Party Shelly Yechimovitz, who proclaimed that the bill was “impertinent, brutal, dictatorial, and hypocritical.” The success by the coalition to pass this law in its first reading might look like a victory for the government, but more than anything else it underlined how divided the political system is in Israel.

One of the most disturbing, though ridiculous, accusations levelled at the Arab parties, is that it will be their fault if they do not pass the newly set threshold, as they split the Arab vote by running in three to four parties.

Clearly the two most vulnerable communities affected by raising the entry threshold to the Knesset are the Arab parties and the Haredi (ultra-orthodox); hence both of them feel victimised by this measure sensing that it was a deliberate attempt to exclude them from political life in Israel. One of the leading Arab MKs, Ahmed Tibi, stood silently with his back to the plenum, describing his act as symbolic of the attempt to silence the voice of the Arab voters. Another MK bluntly accused the bill’s initiators of “the political transfer of the Arab population.” No one can blame either the Haredi or Arab parties for being suspicious of the motives behind the bill considering that the party that introduced it was Israel Beitenu, which is fundamentally anti-Arab and secular in its ideology. Yet, both communities believe that time is on their side because the Haredi and Arab communities are the fastest growing in Israel. The sudden alliance between these two parties is ironic in that both have had very different political experiences regarding access to power in Israel. While the Haredi parties have been extremely privileged and over-represented in past Israeli governments, Arab parties have always been excluded from the corridors of power, and were consequently deprived equal share of access to resources.

Admittedly the Israeli political system suffered from the presence of multiple parties in the Knesset, following each of the elections, and lack of stability, which led to 33 governments in 65 years. However, the mushrooming of small to medium size parties represents the failure of the bigger parties to attract support from certain segments of the society. The existence of small parties generally represents deep divisions within the social-political-economic system. While bigger parties in the Knesset and the forming of a government with fewer parties might be desirable, it should not be at the expense of allowing a voice for all citizens in the political process.

MK Amed Tibi, United Arab List – Ta’al, stands with his back to the Knesset in silent protest at the governance bill.

One of the most disturbing, though ridiculous, accusations levelled at the Arab parties, is that it will be their fault if they do not pass the newly set threshold, as they split the Arab vote by running in three to four parties. This argument is subliminally racist, as it assumes that the Arabs in Israel are not entitled to have diverse opinions. There is an implied expectation that the Arab-Israeli community is monolithic in thinking and aspiration, and therefore should not have more than one party in the legislature.

This is of course complete and utter nonsense. Yet, one of the positive outcomes, if this legislation is passed, might be re-alignment of the political system and rethinking of the nature and function of parties in Israel. The constant decline among the big parties in Israel epitomises the failure of the catchall parties to build trust with the electorate. They often fail to represent significant segments within the Israeli society and provide for their needs. The new legislation may provide a temporary solution, but not a long term one for the array of divisions within the society along religious, ethnic, ideological and socio-economic cleavages.

Quick fixes to chronic flaws

The controversy over the raised entry threshold diverts attention away from other parts of the bill, which are a mixture of quick fixes to chronic flaws in governmental structure, as well as an attempt to limit the Knesset’s ability to oversee and check government’s activities. For instance, few would argue with the need to limit the number of ministers in government as the bill suggests, considering the inflated number of ministers and the expensive ineffective Israeli governments in the past. On the other hand, the new legislation also requires an absolute majority in the Knesset (61 votes) to bring down a government in a vote of no confidence, and makes it harder for the opposition to replace the prime minister during the life of the parliament. This mishmash of legislation cannot guarantee either stability or more democratic arrangements in the Israeli society because it addresses the mechanics of the democratic system, and not the values of such a system.

What is missing from the new legislation is a constitution-like comprehensive approach. Such an approach will not only create a more efficient and streamed line government that can shape and execute policies, but will also include checks and balances to protect basic rights. Since its inception, Israel avoids a holistic approach to this problem by constantly delaying the writing of a constitution. The approach of resolving political crisis or short term difficulties through legislation has failed time and again. This might also be the case with the new Governance Bill unless it is amended in order to avoid minimising democracy in Israel even further.

Yossi Mekelberg is an Associate Fellow at the Middle East and North Africa Program at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House, where he is involved with projects and advisory work on conflict resolution, including Track II negotiations. He is also the Director of the International Relations and Social Sciences Program at Regent’s University in London, where he has taught since 1996. Previously, he was teaching at King’s College London and Tel Aviv University.

You can find him on Twitter @YMekelberg.

MK Adi Kol suspended from Yesh Atid for failing to support the governance bill. Photo by Tomer Appelbaum.

Israel’s dying democracy

Our representative democracy never developed. On the contrary: It is dying or nonexistent in the workplace, the local government, the military, and the occupied territories.

By Yitzhak Laor, Ha’aretz

August 05, 2013

Democracy grants its subjects the rank of citizen by means of their vote. In exchange, the citizens must obey the law and the rules of the game. Once every four years, or fewer, they are asked to choose their rulers and give them legitimacy once again. As long as the voters do not take their representation too seriously, this is an excellent deal from the perspective of the regime, which is based on a majority and, in the absence of a constitution, can do almost anything it wishes. It can even sing nonsense, including analogies with “the Western democracies” regarding the so-called governability law and the electoral threshold.

In various democratic regimes, the power of the state is decentralized in various ways. It is too easy to natter on about the high electoral threshold in Germany and not know that there are also 16 elected administrations in the states of the federal republic, and the right to vote there is broad and has a greater influence than our own does. In Italy, representation is decentralized — in other words, the citizens can influence their future — over the administrations of 20 regions and 110 provinces. In some countries, even judges are elected by the public. Israel has none of this kind of representation except for the Knesset elections. In addition, the State of Israel has no constitution, so the country can discriminate against its Arab citizens and disregard their right to vote.

But the MKs’ ignorance, in the latest debate over “governability,” speaks for itself: The overlords have no need of persuasion. All they need are worn-out cliches and an overwhelming vote. Yesh Atid and Lieberman’s party fight against minorities for precisely that reason. This alliance is nourished by the same hostility to democracy as a mosaic, a hostility that you meet among army officers and among the financial elite under the slogan: “Why are people trying to stop us from doing our job?” What job? The job of ruling. It’s no coincidence that both of these well-disciplined parties, which are fighting to raise the electoral threshold, were appointed and are controlled by the bosses. For them, this is democracy. Representation from above.

MK Adi Kol of Yesh Atid is an illustration of the coarseness of her party colleague Ofer Shelah and his overlord. The fact that Israel has always been a society with wretched representation, given to the subjects as an act of grace, is more important: “Be grateful that we brought you to a democracy.” Indeed, millions of immigrants were brought here and were immediately granted “veteran” representation by the government: functionaries in the various institutions, from the Jewish Agency to the Mossad, Iraqis, Moroccans, Yemenites, Romanians. That is how the Mizrahim were represented in the 1950s and the 1960s; that is how the immigrants from the former Soviet Union were organized over the past two decades in politics by those who came as Zionists in the 1970s. The Arab minority had mukhtars who “represented” it during the military administration.

Our representative democracy never developed. On the contrary: It is dying. Democracy is disappearing in workplaces — in other words, the places where workers once chose their unions in the most central arena of their lives, where they earned their livelihood. Local government is entirely dependent on the government and the Arrangements Law. The army — a state within a state — is, of course, immune to any representation. Add to that the millions of subjects of the occupation, who have no representation (our “referendum” about their future is the most obvious expression of this rottenness), and you’ll get the master’s face of the state. A certain amount of power for the weak is “extortion,” like the government and the media call the political power of small minorities. Now, imagine a new Mizrahi party as an opposition to the ruling hegemony; with an electoral threshold of three or four percent, does it have a chance?

This is also an explanation for the populist comments on the Internet, online petitions that address no one but the glass ceiling, the viral smearing, and even the “Turkel scandals.” They stem from powerlessness, from lack of ability to truly influence our future. We are left with a cynical parliament, an automatic majority and hedonistic elites that want only to increase their power. Where exactly can the masses have any influence? In the voting for “Big Brother” and “A Star is Born.”

Yesh Atid MK ‘harshly’ sanctioned after abstaining in governability vote

Party suspends Adi Kol from membership on Knesset committee and from proposing laws after she violated coalition discipline and failed to support the bill, one of the key issues in Yair Lapid’s domestic policy.

By Jonathan Lis, Ha’aretz

August 1, 2013

MK Adi Kol (Yesh Atid) on Wednesday was suspended by her party from membership on Knesset committees and from proposing laws until further notice after she abstained from voting on the so-called governability law, a move judged by some as harsh and heavy-handed.

A few minutes after the vote on the bill that would make several changes in the system of government, including raising the electoral threshold from two to four percent, Kol was forced to apologize publicly for violating coalition discipline.

“Today I abstained from voting on the governability law, she said in a statement. “That was a decision that harmed mainly members of my faction and I apologize.”

Kol has been known as one of the leading opponents of the law, which was sponsored by former Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu party and also championed by Yesh Atid chairman Yair Lapid. The sanctions brought against her were criticized by opposition MKs, including MK Yitzhak Cohen (Shas), who said in a Knesset speech: “In Yesh Atid they did to Adi Kol what is done to some members of parliament in North Korea.”

In the hours preceding the Knesset vote, various MKs were lobbied by the law’s opponents. A Facebook page featuring the phone numbers of several MKs, including Kol’s, was created, urging users to contact them and voice their reservations.

“In a few hours from now there will be a vote on the scandalous governability law,” the page read. “At the moment we need only four MKs to block one of the most dangerous laws ever seen here.”

At the conclusion of a stormy debate the law passed first reading. Originally formulated by Yisrael Beitenu, it won Yesh Atid’s support after Lapid’s party withdrew a competing version they had submitted. Many opposition MKs used their allocated three minutes and remained silent on the podium in protest against the law, which is seen as targeting mainly Arab parties.

In response to the sanctions against MK Kol, opposition leader Shelly Yacimovich and Labor Party Chairman Isaac Herzog said their party would let Kol use their private bills quota. “The Labor faction will allocate to MK Kol, whenever she so desires, a quota of private bills in order to help her to bring her world view to parliamentary and public expression,” they said. “We will honor any request by MK Kol because we respect her world view and object to the attempt to silence her.”

For previous article, see Knesset votes Arab parties out and overwhelming government power in, May 8th, 2013