The fight to reconcile democracy, Islam and security

A collection of responses to Islamism and to Egyptian uprising no.2:

1) Free Arabs: ‘To protest the confiscation of the constitution by one single party’, 12 year old Ali Ahmed succinctly explains why he is protesting, video;

2) Israel strikes at jihadist threat in Sinai, six weeks before, the view from Israel;

3) Between admiration and cynicism: Mixed opinions of the Egyptian revolution in Israel;

4) Nicholas Gjorvad: A difficult year for Islamists;

5) Amos Harel: Israel, Hamas spectating attentively as Islamists and rivals clash in Egypt;

6) Ma’an news: Nations across Mideast welcome Mursi’s ouster;

7) Ahram, BBC: Egypt’s National Salvation Front, and the Tamarod protest movement;

To protest the confiscation of the constitution by one single party

For a 12 year old’s succinct summing up of why he was against the Muslim Brotherhood government, see this Free Arabs video here

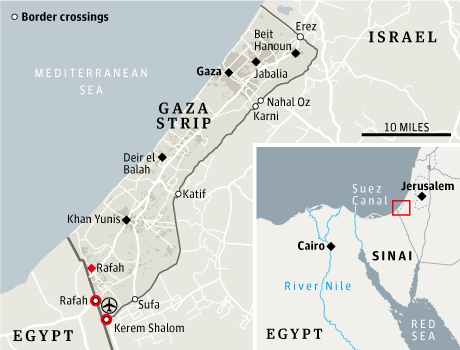

The Nahal Oz crossing was closed in 2010; the Katif crossing existed solely for the then-Gush Katif settlement; the Karni crossing was permanently closed by Israel in 2011; the Sufa crossing opened briefly in 2011 to allow in construction materials for a housing project; the Kerem Shalom crossing is where a limited number of vehicles can carry commercial goods from Israel into Gaza; the Kerem Shalom crossing is supposed to be for the import of humanitarian aid, but is intermittently closed by Israel.

Six weeks before, the view from Israel,

Israel strikes at jihadist threat in Sinai

From UPI, May 02,2013: Israel says its air force this week assassinated a key militant leader operating in the Sinai Peninsula, underlining the Jewish state’s concern about the growth of al-Qaida-linked groups on its southern border. This alarm is heightened by Egypt’s inability to crack down on the swelling jihadist organization in the vast wasteland that stretches to the Suez Canal in the east and the Red Sea in the south as the newly empowered Muslim Brotherhood struggles to consolidate control in Cairo.

The animosity of Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi, a veteran Muslim Brotherhood leader, toward the Jewish state, and the growing dangers Israeli commanders perceive in Sinai have heightened fears that Israel’s historic 1979 peace treaty with Egypt is in peril. If the peace pact does collapse, the geostrategic consequences for the Jewish state, and beyond, could be immense when added to the danger of an Islamist regime emerging in war-torn Syria to the north. Morsi cannot openly act against Israel, despite the antipathy of most of Egypt’s 82 million people toward the 1979 treaty, which they consider a humiliation. But Morsi’s held in check because of international pressure, particularly from the Americans and Europeans on whom he depends for economic aid, to observe it rigorously.

On Tuesday,[April 30] the Israeli military said that Haitham Masshal, 24, was killed in an airstrike in the northern Gaza Strip as he rode his motorcycle. It was the first assassination carried out by the Israelis since an Egyptian-brokered cease-fire ended eight days of fighting in November, largely between Israeli warplanes and Palestinian rocket units [sic]. The military said Masshal was a “global jihad-affiliate terrorist” who took part in an April 17 rocket attack on the resort city of Eilat on the Gulf of Aqaba in southern Israel.

Two rockets were fired from Sinai but caused no casualties and minor damage. The attack was claimed by the Mujahedeen Shura Council in the Environs of Jerusalem. The MSC, an amalgam of several militant cells, acknowledged in a statement that Masshal, aka Abu Zaid, was a member of that organization and had formerly had a senior position in the al-Qassam Brigades of Hamas, the fundamentalist group that has ruled Gaza since June 2007. MSC leaders and other jihadist groups are reported to be funneling large amounts of weapons, mostly from Libya, into Sinai despite lackluster Egyptian efforts to halt the traffic.

In recent months, the Israelis have targeted other jihadist chieftains in Gaza. On Oct. 7, 2012, Talaat Halil Mohamemd Jarbi, ar “global jihad operator,” and senior MSC official Abdullah Hassan Maqawai were killed in an airstrike. Six days later, another raid killed Abu al-Walid al-Maqdisi, former emir of the Tawhis and Jihad Group in Jerusalem, and Ashraf al-Sabah. Both identified as MSC leaders.

Post-1979 relations between Israel and Egypt were never warm and were often downright frigid. But the Israelis accepted that the treaty meant they could demilitarize their southern border and focus on threats from other directions. The Israelis want Morsi to do more to crack down on the Sinai groups but Cairo has long neglected the peninsula, which accounts to some degree for the emergence of militant forces there.

Between admiration and cynicism: Mixed opinions of the Egyptian revolution in Israel

While many Israeli media reports praise the crowds who led the overthrow of Mohammed Morsi, conservative writers continue to view the Arab Spring with skepticism. The common view is that the regional turmoil relieves some of the pressure on Israel over the Palestinian issue.

By Noam Sheizaf, +972

July 04, 2013

In the morning following the overthrow of Egypt’s Mohammed Morsi, there isn’t a single unified voice coming from Israeli officials and the national media. While some pundits welcome the Muslim Brotherhood’s removal from power (pointing mainly to its very hostile rhetoric towards Israel) others think that Morsi ended up being surprisingly cooperative with Israel. The Egyptian army is widely recognized as the single most important institution in maintaining the 1979 peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, but the chaos that the second Egyptian revolution will bring seems like the real danger.

In the left-leaning daily Haaretz, Anshel Pfeffer points to four reasons “Israel would miss Morsi”: that he didn’t support Hamas and was efficient in bringing a ceasefire during November’s Pillar of Cloud operation in Gaza; that he operated decisively against the Gaza smuggling tunnels and militants in the Sinai Peninsula; and that he didn’t get close to Iran. The most interesting argument Pfeffer raises is one I didn’t see anywhere else:

Morsi’s tenure was the first in which a large and popular Egyptian party that was elected in a democratic process supported, even if begrudgingly, the peace treaty with Israel, and justified it to the Egyptian people.

I would add that this is was a precedent not only with Egypt, but with the entire Arab world.

Ynet’s military correspondent Ron Ben Yishai has a piece this morning on “the Revolution’s Hangover,” referring to the challenges the army is facing today. Ben-Yishai thinks that as far as Israel is concerned, it appears Morsi’s ouster will not have a direct effect on us, certainly not in the short term.”

Also in Ynet, an interesting op-ed by the chairman of the Chaim Herzog Center for Middle East Studies presents a much more admiring tone. “Egyptian society’s show of force proves that forecasts of ‘Islamic winter’ were detached from reality,” writes Yoram Meital in a piece titled, “Arab Spring still here.”

The conservative pro-government daily Yisrael Hayom displays a much more cynical tone. The paper’s top pundit, Dan Margalit, attacks the Obama administration for aiding Morsi’s regime. The administration, writes Margalit, learned that there are no moderate Muslim Brothers. “Israel has no reason to be sorry [for Morsi’s departure],” concludes Margalit.

Also writing in Israel Hayom, Prof. Eyal Zisser called Egypt “a military democracy.” Zisser estimates that the army and the Brotherhood – “the only substantial organized forces in Egypt” – will continue their battle in the years to come, with the masses of protesters deciding who has the upper hand.

Also on the conservative side, The Jerusalem Post argues that “Jerusalem prefers the devil it knows to the unknown.” A report in Maariv cites unnamed sources who fear that “terror groups will take over the Sinai Peninsula.“ Maariv’s leading conservative pundit, Ben Dror Yemini, argues that despite the revolution, “the Egyptian pulic is getting more religious.” Yemini warns of “the illusion of the Facebook generation.”

On social media platforms I read some comments in Hebrew concluding that the “Arabs” cannot sustain a functioning democracy, while others admired the activism of Egyptian youth who took to the streets in such large numbers. It is worth remembering that some people argued in 2011 that the Arab Spring, and especially the Egyptian revolution, served as inspiration to Israel’s Tent Protests (in the largest Tel Aviv rallies there were signs specifically quoting slogans from the Egyptian revolution). Today, some lamented the fact that there is little hope of an Israeli protest movement re-emerging.

Perhaps most interesting is the way a clip of an Egyptian journalist and protester speaking in Hebrew with the Israeli Channel 10 went viral. Heba Abu Saif was positive and engaging, urging Israelis to take to the streets whenever their leaders bread their promises or compromised the public’s rights. You can watch the clip with English subtitles here.

A couple other issues I noticed in the past few days:

Reports on sexual assaults in Tahrir Square received a lot of attention in the Israeli media, and sometimes their coverage overshadowed the rest of the revolution, especially until yesterday evening when the attention went back to the fate of the presidency. At times, those reports were used by right-wing commentators for notes on “the real nature of the revolution” in a way that gave the impression it is not the fate of the women who were assaulted they were worried about, but rather some point they were trying to make about Arabs or Muslims in general.

There was also a feeling that the pressure on Israel “to do something” with regard to the status quo in the Occupied Territories would decrease again. With Syria torn by civil war and Egypt is descending into chaos again, many Israelis feel that the attention given to the Palestinian issue is absurd. While I obviously don’t share that view, I think that it is true that as long as the West Bank is “quiet,” some foreign powers will quietly welcome the stability provided by the occupation and the Palestinian Authority, and Israel will be free from pressure (or any other form of accountability), at least as long as it doesn’t take overly drastic measures on the ground.

The opposing view, according to which the Arab Spring presents an opportunity for Israel to resolve the Palestinian issue and find its place in the “new Middle East” – among other things, due to the collapse of any real threat against Israel – is held by a very small minority. There is very little, if any, domestic pressure for change.

The future of Islamism part 1: A difficult year for Islamists

By Nicholas Gjorvad, Daily News Egypt

July 6, 2013

This is the first of three articles discussing the future of Islamism in Egypt and the Middle East. Today’s article will review the various setbacks of Islamist parties in the region not long after impressive electoral victories. Part two will explore the path that Islamism takes from here and whether the Islamist project can adapt to the strong pushback it experienced in recent months. Finally, part three will provide an overview of what may become of the Muslim Brotherhood after the ouster of Mohamed Morsi.

It seems not long ago that many of us were discussing the impressive electoral victories of Islamist parties around the region. The electoral victories of Islamists after the Arab Spring were not surprising in light of the organisational superiority possessed by Islamist groups. The question for many was not whether Islamists would score impressive electoral victories, but whether or not they would live up to the democratic ideals they voiced and promised to support.

For several years, there has been debate among researchers, journalists, and liberal political activists as to whether Islamist groups could truly operate within a pluralistic and democratic system. For many, the electoral success of the Ennahda Party in Tunisia, the Justice and Development Party in Turkey, and the Brotherhood in Egypt have provided a chance to determine whether Islamist parties would live up to their rhetoric concerning their support for democracy and the democratic process. While all three parties have unique histories and operate in different political environments, all have at times exerted their political power in the form of actions which were seen as heavy-handed and counter to democratic norms. In all three cases, the pushback occurring in the first half of 2013 from opposition movements has stemmed from what opponents have seen as a series of unilateral moves by the Islamist leaders.

Tunisia was gripped by mass protests in March after the assassination of liberal politician Chokri Belaid, which culminated in the resignation of Islamist Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali. Jebali’s resignation came after his own party refused to back his request to form a technocratic cabinet in response to the crises, furthering the belief that Islamists were seeking power only for themselves after a decisive victory in parliamentary elections. While the assassination of an opposition politician was certainly a significant impetus for the protests, the underlying frustration concerned the apparent authoritarian nature of the Islamist ruling party. To many non-Islamists, it seemed as though Ennahda was attempting to push an Islamic agenda in a historically secular state while showing apparent indifference to the increasing assertiveness of ultra-conservative Salafis in Tunisia. Mass protests have subsided since then although there have been reports of a Tunisian Tamarod signature campaign circulating, which has garnered thousands of signatures already. While the Islamist Ennahda party is still in control of the government, its position does not look nearly as strong as it did last year and remains on shaky ground.

Less than a month ago, Turkey’s Islamist Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, ordered the destruction of a park in the famous Taksim Square located in central Istanbul. While there were several protesters who were concerned about the destruction of the park on environmental grounds, the mass protests which arose were symptomatic of the increasingly assertive rule of Erdogan and his ruling, Islamist-leaning party. The result was large-scale protests against an Islamist party which many perceived as making a number of moves unilaterally. While Erdogan retains a strong grip on power due to several large parliamentary victories, there remains a great deal of tension about an Islamist leader whose recent legislation has put restrictions on the sale of alcohol and, according to some, is attempting to sneak religion back into a staunchly secular state. For some, the past Taksim Square protests have largely stained an Islamist party which was hailed as the model for the harmony between Islamism and democratic values.

Lastly, the recent events in Egypt seem to have dealt a decisive blow to the Islamist project of the Brotherhood. The enormous protests beginning on 30 June were driven by many factors. First and foremost, opponents were outraged at the power grab by Morsi and his Brotherhood backers which neglected the democratic process and the inclusion of other parties. The Brotherhood subsequently placed many members or supporters of the group in positions of power, and the theory of the “Brotherhoodisation of the state” was easily backed by a plethora of evidence. Additionally, the lack of economic improvement for Egypt contributed to the significant turnout in the streets that ultimately doomed Morsi.

In the short time since the ouster of Morsi, it is difficult to determine the severity of the backlash against Brotherhood leaders and the organisation itself. Some have already called the fall of Morsi and the blowback against the Brotherhood to be the most critical challenge for the organisation to date. While the extent of the damage to the Brotherhood remains to be seen, its grand vision for Egypt seems to be permanently lost.

The common theme associated with the resistance to Islamist parties is the unilateral decisions made by leaders and their dismissive attitude to their opponents. Democracy, as many have recently pointed out, is more than merely winning elections. In each case, opponents of the Islamist governments have identified the issues as the absence of political pluralism, the Islamist inability to form an inclusive government, and the lack of respect for human rights, as the primary evidence for the Islamist democratic setbacks. Several have also argued that Islamists believe that democracy involves winning 50% +1 of the vote and nothing more. The victors, then, would possess the appropriate legitimacy to govern as they see fit. In each case, it appears as though concerns stemming from political power grabs fell upon deaf ears of the Islamists who believed that their electoral victories served as a mandate for their rule and provided them with unlimited amounts of legitimacy even in the face of widening resistance and pushback from their opposition.

I am sure that more analysis of the failure of the Brotherhood in Egypt will appear in the coming weeks, but I would imagine that few would believe that Islamism in the Middle East itself is dying. While some anti-Islamist opponents in the Middle East may now be joining neo-conservatives in the West in pointing out that Islamists can simply not be trusted in politics, it is important to ask whether the situations in Tunisia, Turkey and Egypt are symptomatic of Islamism itself, or rather can be attributed to power hungry leaders of Islamist parties. Part two will address how Islamists may proceed in light of claims that their ideology does not mesh with democracy and investigate how Islamist movements may evolve after these recent events.

Nicholas Gjorvad is a political researcher. He holds Masters degrees in both Philosophy and Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Edinburgh.

Israel, Hamas spectating attentively as Islamists and rivals clash in Egypt

Forced departure of the Muslim Brotherhood from power is no guarantee there won’t be violence, nor does it solve any of the problems facing the country. Either way, the implications for Israel are unlikely to be immediate.

By Amos Harel, Ha’aretz

July 05, 2013

To outside observers, the scenes in Tahrir Square on Wednesday night this week stirred almost instinctive solidarity, even enthusiasm. For the second time in less than two-and-a-half years, the Egyptian people have cast off a regime, though this time it happened early on, at the stage when the president had just begun to show signs of embarking on the autocratic path of his predecessor. As in January 2011, the current revolution has assumed a form that was very convenient for the West to accept: democratic, relatively liberal, patently nonreligious.

In the previous round, the liberals’ good intentions were quickly subdued in the struggle against the well-organized Muslim Brotherhood, which had planned its moves meticulously. This time, the Egyptian army is taking a more active line than it did in 2011. At this stage, however, there is still no way to know clearly whether the temporary unification of forces, including the liberal camp and the army, will be capable of overcoming the Islamists in the long term, or whether that can be achieved without plunging the country into a bloody civil war.

In the summer of 2013, as in the winter of 2011, the army is, at least at the declarative level, assuming the role of the responsible adult. That role, in light of the president’s behavior − which has made him anathema to the electorate − is to tell the rais: “Enough.” But it is easy to forget that last time, a military move ended in an abysmal failure for the generals.

To begin with, the Islamist parties − the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis − won the country’s first free elections decisively. Shortly thereafter, President Mohammed Morsi succeeded in ridding himself of veteran army officer Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, and carried out an effective purge of many high-ranking personnel in the military. His excuse: the chaos that had erupted in the Sinai Peninsula after the attack last August in which Salafi extremists killed 16 Egyptian policemen.

Adly Mansour, chosen by the military to be Egypt’s interim president. He is a 67-year-old judge whose political views, other that not wanting a system which will throw up tyrants, are little known.

It is possible that the new temporary boss, Chief of Staff Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, is, in addition to being younger than the elderly Field Marshal Tantawi, also more determined. Outwardly, Sisi is pursuing the same approach as his predecessors. As was the case in Turkey until a decade ago, the army is presenting itself as the emissary of the Egyptian people and the defender of the country’s democracy and the nation’s interests. Morsi was ousted because he went too far, both in his attempt to arrogate to himself exaggerated powers and in the way he managed the economy. But the army also immediately announced a new civilian authority, in the person of the chief justice of the Supreme Constitutional Court, Adly Mansour, as a temporary replacement for Morsi. How temporary is anyone’s guess, but this means the generals were able to deflect some of their opponents’ allegations that they had staged a military coup.

Behind the scenes, the army has interests of its own: safeguarding its vast financial assets; maintaining the strategic relations with the United States (and, for the same reason, continuing to uphold the cold peace with Israel); and ensuring continued U.S. economic aid.

In both the 2011 and the 2103 revolutions, Egypt seemed to be inching toward a civil war that could have resulted in a bloodbath on a vast scale. In 2011, when it became clear that the regime could not remain in power without perpetrating a massacre of the demonstrators, Hosni Mubarak and the generals backed down.

Observing these events, Syrian President Bashar Assad apparently drew his own conclusions and applied them assiduously when the civil war broke out in his country a month later. In Syria, not just the regime but the entire Alawite community is conducting an all-out war of survival. The result, more than two years later, is a country in ruins and more than 100,000 people killed.

Could a similar fate befall Egypt? There is no clear ethnic rift there and no alliance between the other communities against the Sunnis, as is the case in Syria. But the huge demonstrations by rival entities in Egypt over the past week show that the country is torn almost equally between two large camps: the Islamists and their adversaries. The possibility of a continuing deterioration, accompanied by spiraling violence, still exists. Nor does the removal of the Muslim Brotherhood from power solve even one of Egypt’s long-term problems, in particular the acute economic crisis and the loss of the citizenry’s sense of security. The tumultuous events are taking place as the summer is beginning and ahead of the month of Ramadan. Egypt is in for a long, hot season.

The Muslim Brotherhood was undoubtedly surprised at the alacrity and forcefulness with which the army deposed Morsi. Until the movement gained power, it planned its moves carefully. But navigating the ship of state proved more of a challenge. Still, those who observed the Islamist movements’ takeover of this and other Arab states through a deterministic prism − as a one-way ticket − are now being proved wrong. It turns out that in Egypt, at least, there are forces strong enough to fight back. It remains to be seen whether this setback will have implications for the regional status of the allies of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood in countries such as Turkey and Qatar, and vis-a-vis the role of the Brotherhood in the struggle to topple the Assad regime in Syria.

Iran sidelined

For Israel, the implications of what is going on in Egypt are neither immediate nor far-reaching at this stage. Security coordination was actually strengthened during the Morsi period; the president turned a blind eye to the effective ties between his security forces and the Israeli defense establishment. There is no reason to expect a change in this state of affairs in the wake of Morsi’s violent removal from office. The next Egyptian regime, too, is likely to condemn Israel publicly and coordinate positions with it secretly.

Especially attentive to the developments in Egypt is the Hamas government in the Gaza Strip. In the past year, the organization’s leaders pinned their hopes on the alliance with the sister movement in Cairo, which provided them with strategic backing. Despite the longstanding support for Hamas by Assad and by his father before him, the organization took an anti-Assad line in the Syrian conflict, and consciously pulled away from the Iranian bear hug. Hamas linked itself to Egypt, Turkey and Qatar (Qatar also gave Hamas considerable economic aid). There was a price to be paid for this shift: Iran greatly reduced its arms-smuggling into Gaza (in part because these efforts encountered mysterious bombings in Sudan and more effective Egyptian interdiction in Sinai), and Egypt forced Hamas to desist from violence against Israel along the Gaza border. Israel is now waiting to see whether this delicate balance will be disrupted in light of the events in Cairo.

In the days leading up to the president’s ouster, the Egyptian security forces demanded that Hamas block completely the passage of activists from Gaza to Sinai. The Egyptians were concerned that Gazan Palestinians from Islamist organizations would join terrorist attacks being perpetrated by extremist Bedouin groups in Sinai, or might even try to intervene in developments in Cairo themselves. Hamas complied with the demand to the letter.

The Gaza connection

The crisis in Egypt is already being felt economically in the Gaza Strip. In the week before Morsi’s removal, the Egyptian army reinforced the roadblocks in Sinai and impeded the smuggling of goods through the Rafah tunnels into Gaza. In Gaza, as in Egypt, a fuel shortage has developed. The Gazans are concerned that they will have to go back to importing fuel from Israel, at a far higher price than what they pay for fuel brought in from Egypt. Gaza is also partially dependent on Egypt for its food supply. Instability in that country is liable to force Gaza to increase food imports from Israel. Within a few weeks, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu could find himself calling a meeting to decide whether to help Hamas feed the Gaza masses.

At present, it’s in Israel’s interest to help Hamas preserve stability. Since the conclusion of Operation Pillar of Defense, last November, an unofficial honeymoon has prevailed between the two sides. The statistics are amazing: In the first six months following the operation, only 24 rockets were fired into Israel, compared with 171 rockets in the parallel period after Operation Cast Lead, in 2009. Hamas established a special security unit, whose primary task is to restrain the smaller organizations and prevent the firing of rockets into Israel.

Hamas has thus acceded to Egyptian pressure, though the calm probably reflects an even broader approach by the organization. Preserving the government in Gaza and improving the economy have a higher priority at the moment. Last week, speaking at the funeral of a relative (who died of natural causes), Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh warned that the Islamist organization is preparing “surprises” for Israel should it attack again. While that sounds like a line from Hezbollah secretary general Hassan Nasrallah, for the time being Hamas apparently does not seem to want to rock the boat.

The organization’s military wing is now busy preparing plans for relatively complex attacks, to be implemented when the order is given, as well as testing missiles. It can be assumed that dozens of such tests have been conducted in Gaza since the end of Operation Pillar of Defense, with Hamas extending the range of the missiles to 75 kilometers − covering most of Metropolitan Tel Aviv − as an alternative to the cessation of the smuggling of Fajr-5 missiles from Iran.

Nations across Mideast welcome Mursi’s ouster

By AFP/Ma’an news

July 06, 2013

BEIRUT – Governments across the Middle East on Thursday welcomed the ouster of Egypt’s Islamist President Mohamed Mursi with varying degrees of enthusiasm, with war-hit Syria calling it a “great achievement”.

In a reflection of tense ties between many regional governments and the Muslim Brotherhood organization from which Mursi hails, reaction to the Egyptian leader’s ouster was almost universally positive.

Israel and its arch-foe Iran gave muted reaction while in Islamist-ruled Tunisia, the cradle of the Arab Spring that swept through Cairo and eventually brought Mursi to power, President Moncef Marzouki ruled out the risk of contagion.

“Could Tunisia witness the same (Egyptian) scenario? I don’t think so…,” said Marzouki, stressing the need to “pay attention” to “serious economic and social demands” by the people.

In Syria, where forces loyal to embattled President Bashar Assad are battling rebels including Islamists determined to topple the regime, an official source hailed the change in Cairo.

“Syria’s people and leadership and army express their deep appreciation for the national, populist movement in Egypt which has yielded a great achievement,” state television quoted the source as saying.

Mass protests that preceded Mursi’s ouster by the army meant the people reject the rule of the Muslim Brotherhood across the Arab world, the source said.

Oil powerhouse Saudi Arabia and the Gulf monarchies of Bahrain and Kuwait congratulated Egypt’s interim president, Adly Mansour.

Saudi King Abdullah also paid tribute to Egyptian army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi for using “wisdom” in helping to resolve the crisis and avoiding “unforeseen consequences”.

There was similar praise for the Egyptian army from the United Arab Emirates.

UAE Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed al-Nahayan expressed “satisfaction” and pledged to boost ties with Cairo that were strained during Mursi’s one-year rule.

Since last year the UAE has been cracking down on Emiratis and Egyptians it accuses of links to the Muslim Brotherhood, and on Tuesday a court jailed dozens of Islamists on charges of plotting to overthrow the government.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki also congratulated Mansour and expressed support for the Egyptian people “who are going through a difficult period,” a statement in Baghdad said.

In Israel, which has had a peace treaty with Egypt since 1979 but strained ties, ministers were tightlipped after reportedly being told by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to refrain from comment.

But an official told AFP on condition of anonymity the government was closely monitoring developments in Egypt, adding that the situation was “causing some concern in Israel”.

Reaction was more muted in Iran, which said it respected “the will of the people” but also called for democratic processes to be respected.

Jordan’s King Abdullah II also congratulated Mansour, saying in a statement: “Jordan supports the will and choice of the great Egyptian people.”

But Jordan’s powerful opposition Muslim Brotherhood called Mursi’s ouster a “military coup” and a “US-led conspiracy”, according to a statement issued after an emergency meeting of the group.

President Mahmoud Abbas congratulated Mansour and praised “the role played by the Egyptian people… in saving Egypt and adopting a roadmap for its future”.

Morocco’s Islamist-led government called for respect for “freedoms and democracy” in Egypt, spokesman Mustapha Khalfi said.

In Qatar, a key Muslim Brotherhood ally, new emir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad al-Thani also sent Mansour congratulations while the foreign ministry said Doha “will continue to back Egypt in its leading role in the Arab and Muslim worlds”.

But pro-government Qatari media carried words of warning for Egypt.

“Egypt has never before been in such a foggy situation… Every political and ideological group now thinks it has the right to rule,” read a commentary in Asharq daily.

TWO OF EGYPT’s REBELLIOUS GROUPS

1:Egypt’s National Salvation Front: It is not a coup

The National Salvation Front says in a statement that it rejects any call to exclude any political current, particularly political Islamic groups, from the national political scene in Egypt

By Ahram Online

July 04, 2013

Egyptian reform leader Mohammed El Baradei, center, speaks during a press conference following the meeting of the National Salvation Front, as former Egyptian presidential candidate, Hamdeen Sabahi, left, and former Egyptian Foreign Minister and presidential candidate, Amr Moussa, right, listen in Cairo, Egypt, Monday, Jan. 28, 2013 (Photo: AP)

The National Salvation Front (NSF) issued a statement early Thursday on the dramatic developments in Egypt congratulating the Egyptian people on their insistence to hold firm to the goals of the January 25 Revolution. The statement also insisted that what has happened in Egypt is not a coup but rather a necessary intervention.

We would like to confirm that what Egypt is witnessing now is not a military coup by any standards. It was a necessary decision that the Armed Forces’ leadership took to protect democracy, maintain the country’s unity and integrity, restore stability and get back on track towards achieving the goals of the January 25 Revolution. We have full confidence in the commitment the Armed Forces made yesterday that their role would remain to be a national one, and not political, aimed at restoring stability, security and fulfilling the economic and social rights of the Egyptian people.

We believe that the joint decisions reached in the meeting yesterday between the Armed Forces and several national forces, and witnessed by respected spiritual figures such as the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar and Coptic Pope, those decisions further confirm that the Armed Forces have no intention to intervene in politics…”

We confirm our strong belief in the right of all political groups to express their opinions freely, and to form their own political parties. We totally reject excluding any party, particularly political Islamic groups. We stress that the achievement the Egyptian people made lately, obliges us to reconcile with all parties, and to confirm that the priority now is to remain united while facing serious challenges.”

NSF statement

2: Profile: Egypt’s Tamarod protest movement

BBC news

July 01, 2013

Tamarod is a new grassroots protest movement in Egypt that has been behind the recent nationwide protests against President Mohammed Morsi, a year after he took office.

The group, whose name means “rebellion” in Arabic, claims it has collected more than 22 million signatures for a petition demanding Mr Morsi step down and allow fresh presidential elections to be held.

Following Sunday’s massive demonstrations, in which millions of people took to the streets in Cairo and other cities, Tamarod gave the president an ultimatum to resign by 17:00 (15:00 GMT) on Tuesday or face a campaign of “complete civil disobedience”.

It urged “state institutions including the army, the police and the judiciary, to clearly side with the popular will as represented by the crowds”.

Tamarod also rejected the president’s recent offers of national dialogue.

“There is no way to accept any half measures,” it said. “There is no alternative other than the peaceful end of power of the Muslim Brotherhood and its representative, Mohammed Morsi.”

Many protests have accused the president of putting the interests of the Muslim Brotherhood, the powerful Islamist movement to which he belongs, ahead of the country’s as a whole. His supporters insist they are not.

‘Astonishing’

Tamarod was founded in late April by members of the Egyptian Movement for Change – better known by its slogan Kefaya (Enough) – which pushed for political reform in Egypt under former president Hosni Mubarak in 2004 and 2005. Although Kefaya joined in the mass protests that forced him to resign in 2011, it did not play a prominent role.

Tamarod focused on collecting signatures for a petition that complains:

● Security has not been restored since the 2011 revolution

● The poor “have no place” in society

● The government has had to “beg” the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a $4.8bn (£3.15bn) loan to help shore up the public finances

● There has been “no justice” for people killed by security forces during the uprising and at anti-government protests since then.

● “No dignity is left” for Egyptians or their country

● The economy has “collapsed”, with growth poor and inflation high

● Egypt is “following in the footsteps” of the US

Tamarod’s activists quickly became a familiar sight on Egypt’s streets, often blocking traffic to hand out petitions. The group also collected signatures on its website, as well as on Facebook and Twitter.

Tamarod says the signatures on its petition have been checked against the electoral register

Mainstream opposition groups soon put their weight behind the campaign, providing logistical support and office space.

By late June, Tamarod said it had gathered 15 million signatures, all of which it insisted had been checked against a recent interior ministry electoral register. Each signatory puts his or her name, province of residence and ID number.

However, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) dismissed the claim, saying Tamarod had only collected 170,000.

On Saturday – a day before the mass protests it organised to mark the first anniversary of Mr Morsi taking office – Tamarod’s total was reported to have reached 22 million, more than a quarter of Egypt’s population.

One of the founders of Tamarod has called the success “astonishing”. “I can’t tell how many members out there. I can think that millions of Egyptians are members,” Ahmed al-Masry told the Associated Press. “At one point, people gave up [on President Morsi]. No-one is heard but the president and his tribe.”