IDF clearance of South Hebron land for firing zone broke laws of occupation

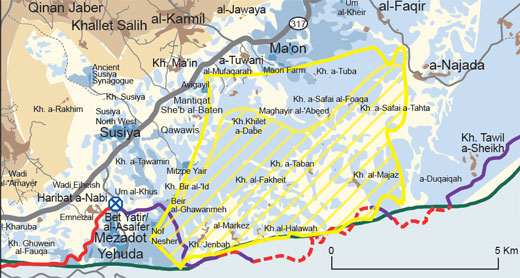

Map of designated firing zone in South Hebron hills

South Hebron Hills: State’s response re firing zone 918 ignores the laws of occupation

By B’Tselem

August 27, 2012

The south Hebron hills area encompasses some 30 Palestinian villages that have been there for decades, since before Israel occupied the West Bank. The villagers earn a living as farmers and shepherds and many live in caves or in temporary structures near the caves, which they use as kitchens, animal pens, or storage areas. During planting and harvesting, other family members come from the nearby town of Yatta to help with the work.

Early in the 1980s the IDF designated about 30,000 dunams in the south Hebron hills area, including 12 villages, as Firing Zone 918. In November 1999 the military expelled over 700 villagers, destroyed their cisterns and confiscated their property – claiming that they were residing illegally in an area declared a “firing zone.” At this writing, some 1,800 Palestinians live in these villages.

Following the expulsion, residents petitioned Israel’s High Court of Justice,some through the Association for Civil Rights in Israel and some through Attorney Shlomo Leker. The HCJ issued an interim order requiring the military to allow the residents to return to their homes pending a ruling on the petition.

In 2005 an arbitration process between the parties was halted without an agreement. In April 2012 the court resumed deliberations in the case and the state announced that the Ministry of Defense had formulated a new position concerning the status of the Palestinian residents of the area.

On 19 July 2012 the state submitted a detailed notification to the court in which it claimed that the petitioners are not “permanent residents” of the firing zone area and hence have no right to live there. The state clarified that the military was prepared to allow the residents to enter the area to work their land and herd their animals on weekends and Israeli holidays and during two other month-long periods during the year. In the northwestern part of the firing zone, where four villages are located, the state announced its intention to conduct only training that did not involve live fire and that these residents could continue to live there, subject to planning and building laws.

Following the state’s announcement, on 7 August 2012 the Court decided that the state’s announcement constituted “a change in the normative situation” and hence the specific petitions “were no longer relevant.” Justice Fogelman dismissed these petitions and stated that the petitioners could submit new petitions. The interim orders obliging the military to permit the village residents to live there and to work their lands remain in force until 1 November 2012. The Court emphasized that the withdrawal of the petitions did not constitute taking a position concerning the residents’ claims.

In an announcement on 7 August 2012, the state clarified for the first time the “operational necessity” in declaring the area a firing zone. In the past, the area had been a training ground for the air force and other units, but due to “the increase in illegal building and the presence of people in the area,” the military was obliged to reduce the training there significantly. Alternative solutions “do not meet the entire operational need,” and moreover this area is actually critical due to the “unique topographical structure of the territory, which enables specific types of small and large scale training, from a squad to a battalion (and, together with adjacent firing zones, even for larger forces).”

Later in the state’s announcement, however, it emerges that the reduction in the exercises has nothing whatever to do with the presence of Palestinian residents in the firing zone. The state explained that between 2000 and 2006, the use of firing zones had decreased in general, “among other reasons in the context of a quantitative reduction in the forces, and the necessity of their engaging in continuous operational activity, given the events taking place in 2000, the Cast Lead campaign and the operational activity that followed, and so forth – all at the expense of the time spent on training.” The second Lebanon war “exposed weak points in the land forces’ readiness, including in the context of the ongoing and increased involvement in the war on terror in Judea and Samaria, which made it more difficult for the forces to train, creating an even more salient need for the forces to return to routine exercises. Meanwhile, the eventual improvement in the security situation and the greater control of the territory due to ongoing activity enabled the units to return to training.” Hence, beginning in 2006 “there was a sustained increase in the scope of training and use of firing zones as an outcome of the changes in the operational needs in the IDF in general and the Central Command in particular.”

The state did not explain in its announcement to the court under what law the military had declared the area a “firing zone” and what the legal justification was for this declaration. The absence of a legal justification is not happenstance, as in fact there is no such justification. As an occupying force, Israel is bound by restrictions regarding the use of the territory and has obligations toward the civilian population. The argument that this is an “operational necessity” is insufficient to justify the taking of territory and an occupying state is not empowered to do as it pleases in land it has occupied.

An occupying state is authorized to act within the occupied territory based solely on two considerations: The welfareof the local population, and immediate military necessity involving the military’s operations in the occupied territory. The occupying state is not authorized to use the land for its broadermilitary needs, such as training for a war in Lebanon or general military training. Certainly it is not authorized to expel residents from their homes, destroy their property and harm their livelihood for such purposes.

Former Israeli High Court PresidentBarak set the fundamental principle concerning the obligation of the military commander in the territories:

The military commander’s considerations are directed to assuring his security interests in the area as well as assuring the interests of the civilian population of the area. Both are directed to the area. The military commander is not authorized to consider the national, economic, or social interests of his country except insofar as they have implications for his security interests in the area or the interests of the local population. Even the needs of the militaryare its military needs and not national security needs in the broad sense. The territory held by belligerent occupationis not an open field for exploitation economically or otherwise.

(HCJ 393/82 Jam’iyyat Iskan al-Mu’alimoun al-Mahdduda al-Mas’uliyyah v. Commander of IDF Forces in Judea and Samaria)

In its announcement, the state completely ignores these principles which are among the foundational principles of the laws of occupation. Instead it skips directly to the question of whether the residents of the villages within the firing zone are permanent residents – a question that is not relevant given the illegality of the declaration of such a zone to begin with. Israel is ignoring its obligation toward the residents, as the occupying power in the West Bank.

Israel must revoke the declaration of the firing zone in the south Hebron hills and allow the residents to live in their homes, work their fields and herd their sheep and goats.

[For an info sheet on the firing range prepared by ACRI with Rabbis for Human Rights and Breaking the Silence click here.]

[Note: 10 dunum = 1 hectare = 2.47 acres]