Historians dispute the effects of Nazi propaganda on Muslims and Arabs

Arabs and Nazi propaganda

Review of “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World”, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009, by Jeffrey Herf.

Reviewed for H-German by T. David Curp, Ohio University

(H-German is a daily Internet discussion forum focused on scholarly topics in German history)

November 2011

The physical detritus of war is deadly. From the unexploded Anglo-American bombs that to this day still claim German lives to the depleted uranium munitions that litter the battlefields of the Middle East, the remains of the weapons designed for the wars of the twentieth century continue their work of physical destruction.

Other remnants of the war cultures of twentieth-century European militarism and imperialism retain a more subtle lethality. At a time when various radical Islamists, including the current president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, call into question the universal condemnation of National Socialist Germany and the Shoah, while the Israeli foreign minister proposes population transfers/expulsions of his country’s Palestinian Arab minority as a means of ensuring peace.Jeffrey Herf’s study of the immediate and long-term impact of Nazi propaganda in the Arab world is a timely call for deeper historically grounded, international analysis of the impact of World War II on the Middle East. Based upon a wide range of English- and German-language archival resources, including American embassy translations of Nazi radio propaganda in Arabic, “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World” examines the desperate Nazi efforts to propagate and weaponize their antisemitic visions and ideals in the Arab world, and the responses of both the Arabs and their Anglo-American hegemons to these efforts.

In the book’s eight chapters, Herf traces the Nazi relationship with the Muslim world (primarily, but not exclusively, among Arabs). In the first two chapters, we see the inauspicious pre-war beginnings of what Herf argues eventually would be a “meeting of hearts and minds” between Arab radicals and the Nazis. Adolf Hitler’s 1933 reflections on Arab racial inferiority in Mein Kampf, efforts to speed German Jewish emigration, even to Palestine, and Nazi racial legislation were not the best of introductions of the new Germany to the Muslim world in the 1930s. The kind of institutional infighting and muddled flexibility that was one of the hallmarks of the Third Reich, however, led to a striking series of Nazi discussions of the principles and practices underlying racial legislation as well as the fitful, opportunistic concessions the regime had made to German Zionists. Those tasked with deepening Germany’s ties to the Muslim world sought to refine and narrow the regime’s antisemitism into a purely anti-Jewish affair and end any overt support for Zionist emigration, while other officials strove–with some success–to preserve a more expansive range of racially discriminatory practices.

The outbreak of war, the ensuing English efforts to ensure control of imperial lines of communication by clamping down on unrest in the Middle East, and the string of Nazi victories over the Anglo-French alliance all created new possibilities for Nazi-Arab cooperation. In the first years of the war, German Middle East experts sought, through an antisemitic reading of the Koran and a Fascist interpretation of Muslim culture, to employ propaganda that nurtured those aspects of Middle Eastern culture which could tie together Arab anti-Anglo-French imperial sentiments with Germany’s and Italy’s war efforts. Herf describes these early propaganda appeals and diplomatic overtures to Islam as suffering from a “slightly academic tone” (p. 53). Such efforts were further undermined by a German diplomatic establishment that was keen to support Italian (and eventually, Vichy) imperial aspirations in the Middle East, and by a jaundiced and racialized contempt [held by] German observers in the Middle East for Arab political and military capacities. In this context, propaganda was a weapon of the (relatively) weak Nazi imperial push into the Middle East, pursuing nonetheless what they judged to be a wavering and fickle potential Muslim ally.

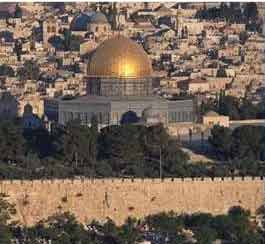

In chapters 4 and 5 Herf charts the takeoff in Nazi-Arab cooperation that occurred with the expansion of Nazi military efforts to North Africa and the emigration to Nazi-dominated Europe of anti-colonial Arab politicians in the aftermath of Rashid Ali al-Kilani’s failed coup in Iraq in the spring of 1941. Of these émigrés, Haj Amin el-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, was to play a key role in facilitating a Nazi-Arab meeting of hearts and minds that resulted in an enormous German investment in constructing an Arab-exile/Nazi propaganda machine. For the next four years, this propaganda machine conducted daily broadcasts and printed millions of leaflets to popularize a hybrid Nazi/Islamist vision of the course and meaning of the war as part of an elaborate conspiracy of “international Jewry” and expound upon the anti-Jewish, anti-Allied political tasks facing the Arab world (p. 170).

In the following chapters, Herf notes how propaganda and Muslim outreach was a weapon that a dying German imperialism continued to grasp and deploy with increasing ferocity (and even less effect) from 1943 until the end of the war. Furthermore, el-Husseini and other Arab exiles [living in Germany] stepped up their collaboration with the Nazis by aiding in the creation of SS (Schutzstaffel) units among Balkan Muslims and (less successfully) Allied Muslim POWs (prisoners of war). Although Nazi/Arab collaborationist propaganda, unsupported by the aura of Nazi military invincibility, had even less of a direct impact from 1943 onwards, it still alarmed official Anglo-American commentators in the Middle East, who reported on and attempted to track its effects while seeking to develop effective counter-propaganda. These Anglo-American efforts both to fathom and influence “the Arab” and his (apparently undifferentiated) responses to Nazi/Arab collaborationist propaganda, particularly its antisemitic virulence, are quite revealing (p. 76).

For many Anglo-American officials, whether they were affiliated with the Allied diplomatic, intelligence, or military services, Nazi propaganda touched “the Arab mind” through “the curiosity, the avarice, the aspirations, the religious instincts, or the racial prejudice, etc.” which they believed beset “it” (p. 218). Other officials, such as a U.S. Military Intelligence official in Beirut in 1944, noted that while “the Arab mind” had undergone “long-term conditioning … by deliberate German propaganda … the Arab mentality is impressed by show of force and strength in arms.” Such analysis (which Herf, in the conclusion, oddly labels as part of a “highly nuanced [Allied] view of the Arab and Muslim responses to Nazi propaganda,” p. 264) led Allied officials to formulate a simplistic counter-propaganda for the Middle East. This counter-propaganda not only assumed the futility of anti-racist appeals but insisted that all “political and ideological themes should be avoided” (p. 172). Instead, American propaganda’s goal for the Arab world was to stress “primarily Allied power and the certainty of victory, with its corollary of enemy weakness, and secondarily, the material benefits likely to follow from the victory of the United Nations and the necessity for making an individual contribution in order to share them” (pp. 172-173). Such arguments from power and plenty not only revealed the orientalizing contempt of too many Anglo-American observers but reflected their belief that there was no good way to increase pro-Jewish sympathy among a Muslim population whom they regarded as inveterately antisemitic.

In chapter 8 and the conclusion, Herf follows the fortunes of the Grand Mufti and movements in the Arab world, particularly Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, that in the postwar era attempted to further popularize antisemitic, anti-Zionist, and anti-imperial agendas that Nazi/Arab collaborationist propaganda had attempted to co-opt and direct. The Muslim Brotherhood’s proto-fascist ceremonies, “unbridled authoritarian moralism” (p. 250), and lionizing of the Grand Mufti upon his return to the Middle East for Herf are suggestive of the deeper impact of Nazi propaganda on the Arab world. He concludes the eighth chapter with a one-paragraph survey of the points of agreement (or antisemitic meeting of hearts and minds) between the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian president Gamal Nasser. In pointing to several instances in which Nasser’s government engaged in antisemitic actions, Herf suggests that that strand of contemporary Islamism’s and Arab nationalism’s intellectual heritage originating in German-occupied Europe is part of a much broader dynamic of Nazi influence. For the Jews of North Africa and the Middle East this hybridized ideology helped efface any distinction between antisemitism and anti-Zionism. The ethno-religious revolution that led to the Middle Eastern Jews’ demonization and eventual ethnic cleansing is, he argues, to an important degree a bequest of Nazi/Arab-exile collaboration to the Arab world.

As a study both of the interrelationship of propaganda to ideology and politics as well as the Third Reich’s capacity to organize on a shoestring a vast information warfare apparatus, “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World” is uniquely valuable. In addition to the operational and organizational issues involved in creating a military-academic-propaganda complex which are covered in detail, Herf’s work provides numerous insights into the national and racial radicalism already growing in the interwar period that would only further metastasize during the war. In the beginning of the book his discussion in the second chapter shows how scientific racist ideals already had deep roots in the Muslim world in the 1930s and helped to prepare the way for Nazi and Arab-exile collaboration. Furthermore, Herf’s analysis of how some Nazis were willing to compromise their racist visions for influence in the Middle East even while maintaining (and propagating) core elements of their antisemitic agenda is a sophisticated reading of the role of an ideology that was neither monolithic or irrelevant to the Third Reich’s statecraft. This combination of significant compromise and core genocidal objectives is brilliantly illustrated in the discussions of the fifth chapter which explores Nazi/Arab-exile efforts to prepare for an expansion of the Holocaust into the Middle East at the height of Axis military success in North Africa in 1942. Herf convincingly demonstrates how the Germans and their Arab allies worked hard to prepare Arab popular opinion to transform Nazi battlefield successes in the Middle East into a program for exterminating the region’s Jews.

While ”Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World”explores important wartime problems and is a solid contribution to the international history of Great Power rivalry in the Middle East, there are problems with its core argument.

Two key issues that Herf touches upon call into question his work’s overarching thesis regarding how direct …is the wartime relationship of the Arab exilic/Nazi propagandists’ work to the later development of modern Islamism’s political theology or Arab nationalism as well as the degree to which the …propaganda was catalytic in merging anti-Zionism and antisemitism in the Arab world. First, of course, are the challenges in evaluating the impact of Nazi/Arab-collaborationist propaganda in the Middle East. This problem is doubly complicated because the content and evaluation of this propaganda is mediated to us through an Anglo-American official mind which Herf demonstrates was itself not free of antisemitism (in both the narrow and broader senses of that term). Moreover, for all of the enormous effort and expense to which the Nazis went in order to incite disorder throughout the Arab world, and in spite of the relatively greater expertise that the Grand Mufti and other Arab exiles lent to this enterprise, the wartime results of Nazi/Arab-exile propaganda were quite meager. Tens of thousands of hours of Nazi radio propaganda and millions of leaflets (developed and expounded by ostensibly popular dissidents such as the Grand Mufti and al-Kilani) produced no direct pro-Axis action even at the high tide of Nazi military power in the Middle East. This suggests that few Arabs took the Nazis, or the Mufti and his colleagues in exile, seriously even at the high-water mark of Axis power in the Middle East.

Secondly, there is the problem of the degree to which Herf argues that Arab concern over Jewish power was simply fanciful as opposed to being founded upon real, if only, local concerns. Herf of course is correct that internationally it is the tragedy of Jewish powerlessness, and not Nazi/Arab-exile fantasies of a vast Jewish conspiracy, that most mark the war. Yet, if World War II gives the lie to the adage that all politics is local, many ethno-nationalist grievances and aspirations that sought to inform Great Power war- and peace-making (such as those of Arabs and Zionists) were intensely parochial. For al-Husseini and many Arabs who looked to him (as well as the many more who looked elsewhere) for solutions to Arab-Jewish conflict, the dilemma of collective Arab weakness in the face of the distinct but related problems of Western imperial power and Jewish colonization in the Middle East were issues of paramount importance.

The Arabs needed no Nazi vision of racial struggle, global Jewish power, or World War II as a “Jewish war” to see a reality of expanding local Jewish power in Palestine, even if their assessments of the place and power of Jews living in the rest of the Middle East were skewed by that conflict. Decades prior to the Nazis in the Middle East many Arabs experienced a growing powerlessness of their own in the face of a (thoroughly understandable) Zionist effort to redouble Jewish settlement in Palestine. This reality was all the more bewildering (and infuriating) both for the degree of sufferance this settlement received from the British Empire (and later progressive opinion throughout much of the West, especially in the United States) and the relatively small, but regionally highly significant support provided by that fraction of the Jewish Diaspora (and some well-meaning and many not so well-meaning gentile sympathizers, some of them in Central Europe) that supported Zionism.[1]

Herf rightly notes that local Jewish power in Palestine masked a catastrophic Jewish weakness internationally. Yet in Palestine Jewish power was sufficient to threaten (and eventually bring about) a regional geopolitical revolution opposed by the vast majority of the Arab world that dispossessed hundreds of thousands of Arabs of a portion of their homeland. Locally, ethno-national conflict had produced for many Arabs a Jewish enemy that was neither primarily the fanciful construct of paranoid Nazi racism nor the product of their own Judeophobic-tinged religious and cultural traditions. Rather, the Jewish enemy in the Middle East was for many of the Arabs in Palestine (and Muslims throughout the world who felt bonds of sympathy with Palestine’s Arabs or concern over Islamic holy places there) the all too real Jewish settlers whose colonial agenda proved unstoppable.

Though Herf’s account is primarily focused on Nazi-Arab collaboration, one of his work’s strengths is its discussion of a range of problems that the unprecedented increase in information/propaganda warfare raised for both the Great Powers and their target audiences. What we learn indirectly both about the contradictions of Great Power propaganda campaigns and their impact on those Arabs who actually exercised political power and cultural influence during the war is telling. Many appear–quite rationally given Allied power in the region–not to have been moved to action by the reactionary modernism of the Grand Mufti’s and his Nazi patrons’ warnings and promises. Rather, a significant number of Arabs who conversed with Western representatives followed much more closely (and seem to have been bewildered by) the independently emerging reactionary post-modernist narratives of Zionist colonial and Anglo-American imperial ambitions in their region. Confusingly for Arabs sympathetic to the Allies, the Anglo-Americans propounded ideals like the Atlantic Charter yet ignored Arab concerns about their application of those ideals to the Palestinian issue as well as their own domination by British–and for a time even Free French–imperialism.

Furthermore, the Anglo-Americans who defined themselves as fighting for democracy against fascism also were indifferent to Arab fears about the implications of cooperation with a Soviet Union that (mis)ruled over wide stretches of the Muslim world in Central Asia and the Caucuses and was then in occupation of (the non-Arab but fellow-Muslim region) northern Iran as well. Many Arabs were troubled by the contradictions in the democratic powers’ alliance with a Soviet Union guided by a totalitarian, universalist Stalinist reading of Marxism-Leninism. That ideology as well as Soviet imperial interests had led the Soviets for over a quarter of a century to build up Communist Party organizations throughout the Middle East and engage in anti-Islamic religious persecution and the deportation or mass murder of many hundreds of thousands of Soviet Muslims. (While Herf notes that Nazi propaganda of the number of Muslim victims of Soviet atrocities was inflated, Nazi accusations that the Soviets were guilty of the mass murder of Muslims were no more incorrect in their broad outlines than was Nazi propaganda over the question of Katyń.) That Allied representatives believed these and other Arab concerns were primarily a sign of Nazi propaganda conditioning of the Arab mind speaks as much to the capacity of the imperatives of information warfare in a total war (or perhaps any long-enduring conflict) to close down argument and critical reflection in Western democracies as it does to any Arab susceptibility to the blandishments of Nazi propaganda.

Reactionary Western postmodernism, caught up primarily if not exclusively with its own fears, visions, and ambitions, led Westerners to ascribe little meaning to Arab concerns. Even Anglo-Americans who were tasked with understanding local conditions and cultures ignored the pleas of the West’s many friends and collaborators in the Arab world to consider local issues from Arab perspectives and within the context of the West’s own professed values. This seems sufficiently important to explain the resonance of Nazi propaganda and its continued subsistence within Arab grievances and Islamist ideologies. Arab alienation appears even more overdetermined given the more enduring legacies Western war cultures created through colonial settlement, expulsion, ethnic cleansing, and genocide in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. During the era of globalized war cultures many peoples’ and states’ fears, hatreds, and interests flowed into often contradictory integral nationalist (and even imperial and colonial) projects. These projects sought (not always successfully) at a minimum to ensure various peoples’ security, independence, and survival even as their maximal goals often entailed implementing a variety of prewar and wartime dystopic projects of ethnic cleansing, territorial expansion, and extermination.

After 1945 the Great Powers with the support of many minor powers sought to defuse some of the worst legacies of hatred and conflict left over from the war to create a new global architecture of secure and stable polities. At that time the policy of choice was to create numerous ethnically “clean” national spaces. The ongoing delineation of such spaces to this day continues to impact the lives of millions of refugees and their descendents in Europe, Israel, and the Muslim world from the Maghreb to Kashmir, since maintaining an ethnically cleansed nation also involves a different kind of daily plebiscite to affirm the purity of a cleansed nation. Continuing to defend (or attack) the ethnically cleansed status quo in these states, politically, militarily, and intellectually, are among the most concrete and powerful legacies of the Second World War, particularly in the Middle East for both Israelis and Arabs. Certainly the origins and consequences of the ethnically cleansed realities of the Middle East are more important in understanding the roots of Islamist (and Zionist) militancy in the Arab world than a Nazi/Arab-exile propaganda that was unable even in its heyday to parley tens of thousands of hours of radio propaganda and millions of leaflets into any jihadist divisions for Hitler or the Mufti, even in Palestine.

Notes

[1]. Francis R. Nicosia, “Jewish Farmers in Hitler’s Germany: Zionist Occupational Retraining and Nazi Jewish Policy,” Holocaust Genocide Studies 19, no. 3 (Winter 2005): 365-389.

[2]. N. Pianciola, “Famine in the Steppe: The Collectivization of Agriculture and the Kazak Herdsmen, 1928-1934,” Cahiers du monde russe 45, no. 1 (2004): 137 gives the total Kazakh losses from the famine of 1931-31 as 1.3 to 1.5 million Kazakhs, between 33-38 percent of the entire Kazakh population (and the highest losses of all collectivized populations). Including the losses of Central Asia and the Muslims of the Caucasus region under Soviet rule (due to a series of bloodily repressed revolts, most famously the Basmachi rebellion of the 1920s but not the high casualties the Soviets caused during the 1944 deportations of the–mostly Muslim–“traitor nationalities” of which Nazi propaganda and its Arab audiences likely were unaware) does mean that Nazi propaganda figures of four million Soviet Muslims dead cited by Herf (p. 100) is inflated. Yet the fact that the death toll approached two million suggests Muslim apprehensions over the Soviet Union’s place in what was ostensibly a union of free peoples fighting fascism were far from fanciful.

[3]. Benny Morris, 1948: The First Arab-Israeli War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 407-415.

Ethnic cleansing – when, where, by whom

Response to David Curp by Jeffrey Herf

06.01.12

David Curp’s extended review of “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World” captures parts of the book’s argument and evidence, gives short shrift to other parts and offers a peculiar conclusion that draws on his own, in my view, mistaken understanding of the postwar years in the Middle East. Readers who want to see the core evidence regarding the fusion of Nazism with Islamism and radical Arab nationalism in wartime Berlin will find it in the book, not the review. Before turning to Curp’s comments about postwar developments, I offer the following two brief comments.

First, the most important Allied interpreters of Arab politics during World War II were the American and British Ambassadors to Egypt, Alexander Kirk and Miles Lampson respectively. Neither made references to “the Arab mind” nor did their reports express “orientalizing contempt.” It was their reports that I found to be “highly nuanced.” Readers of “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World” can observe both [ambassadors’] attention to the details of Egyptian and Arab politics, including anti-Nazi and anti-fascist currents.

Second, Curp goes too far when claims that there was “no direct pro-Axis action at the high tide of Nazi military power in the Middle East.” In fact, the British kept an eye on distribution of pro-Axis propaganda by Arab activists in 1941 and 1942. The tide of German power was high but not quite high enough. British, American and German intelligence agencies were all convinced that a German military victory at Al Alamein in 1942 would have been greeted with enthusiasm by hundreds of pro-Axis Arabs in the Muslim Brotherhood, by young nationalist officers such as Anwar Sadat and Islamist oriented students, some at Cairo’s Al Azhar University. It was these concerns that led the British to place figures such as Hassan al-Banna and others they suspected of pro-Nazi sympathies under house arrest and/or internment during the war.

Curp concludes his review with assertions about the history of the Middle East. He refers to “Jewish power” in Palestine that was “sufficient to threaten and eventually bring about a regional geopolitical revolution opposed by the vast majority of the Arab world that dispos[sess]ed hundreds of thousands of Arabs of a portion of their homeland;” that this “Jewish enemy in the Middle East was for many Arabs in Palestine (and Muslims throughout the world who felt bonds of sympathy with Palestine’s Arabs or concern over Islamic holy places there) the all too real Jewish settlers whose colonial agenda proved unstoppable.” He mentions something he calls “reactionary Western postmodernism,” “globalized war cultures” and to the policies of the Great Powers which supposedly fostered ethnic cleansing of various countries. His implication is that the state of Israel was one of the “ethnically cleansed realities of the Middle East” which “are more important for understanding the roots of Islamist (and Zionist) militancy in the Arab world than a Nazi/Arab-exile propaganda…” I understand Curp to be asserting that he thinks that the establishment of the state of Israel was an example of ethnic cleansing supported by “the Great Powers;” that Zionism was and presumably remains a form of racism; and that it is therefore the sins of the Jews that are the primary cause of the regrettable presence of Jew-hatred in parts of Arab and Islamist politics.

Hence it is important to speak plainly in response and to restate a key argument of the book under review. First, the establishment of the state of Israel was not the result of ethnic cleansing but of a partition plan approved by the United Nations in 1947 which envisioned a Jewish and Palestinian state in what had been pre-state Palestine. The Palestinian refugee crisis was the result of a war launched by seven Arab states and the Palestinian national movement then led by the ex-Nazi collaborator Haj Amin el-Husseini, a war based on rejection of the two-state compromise. Second, hatred of the Jews as Jews was a core element of Islamist ideology by the 1930s, well before the foundation of the state of Israel. This Jew-hatred with important indigenous roots in a selective reading of Islamic texts was one of the, if not the core reason why a resolvable conflict over territory led to war in the first place. Curp cites Benny Morris’s excellent history of the war of 1948 yet fails to convey that Morris, who has done pioneering work on the Palestinian refugee crisis, demonstrated that Israeli policy in 1948 was not one of ethnic cleansing. He has also drawn attention to the Islamist rhetoric about a jihad to drive all the Jews out of Palestine accompanied that Palestinian and Arab armed forces in 1948. Further, the Israelis won the war without the support of the Great Powers but with assistance from a small power, notably Communist Czechoslovakia.

Second, as Curp has introduced the term ethnic cleansing into his review, I’m glad to take this opportunity to remind H-German readers that in 1945 there were between 700,000 and a million Jews living in North Africa, the Middle East and Iran. Today, there are about 60,000 Jews remaining there. That is, these regions were indeed ethnically cleansed of Jewish populations that had lived in peaceful if subordinate relations to their Arab and Muslim neighbors for many centuries. The vast majority of the Jews of Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, people who bore no responsibility at all for the foundation of the state of Israel were driven out solely because they were Jews and because in the political culture of those years, they were held accountable by Arab and Iranian governments and Islamist movements for the alleged sins of Zionism. An exodus of Jews from Iran took place following the Islamist revolution of 1979. So as Curp implies that ethnic cleansing took place where it did not in fact occur, namely in the context of the 1948 war, it is important to focus instead on ethnic cleansing where it did happen, namely in the deportations inspired by racial and religious hatred that produced the massive, and still under-examined, expulsion of Jews from their homes of many centuries.

Scholarship on the relationship between Germany’s secular and religious traditions, on the one hand, and Nazism and the Holocaust on the other, has taken many decades to develop. Important works casting new light on these issues continue to be published now seven decades later. In recent years, scholars in Germany, Israel and in this country have made a good start on the ideological and personal connections and continuities between Nazi propaganda and policy and their aftereffects in Islamist and radical Arab nationalist politics. None of these scholars, including myself, has claimed that the short Nazi chapter in the longer history of Islamism is the only source of Jew-hatred before and after the founding of the state of Israel in 1948. One of the main themes of “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World” is precisely that attention must be paid to the labor of selective tradition both in European as well as in Arab and Islamist contexts that accentuated those elements of the Christian and Islamic religions that fostered hatred of the Jews. Hatred of the Jews had multiple cultural origins and not all of them came from Europe.

Not surprisingly, these arguments have been met in some quarters with a litany of excuses cloaked in the mantle of anti-imperialism and third worldism. Historians of Nazism in Europe know that it has taken a long time to advance knowledge about the roots of anti-Semitism and their links to the Holocaust. We also know that there was considerable resistance from a variety of political and scholarly perspectives to our efforts. We have also explored the echoes of Nazi ideology in contemporary Islamist ideology and politics and this effort has also met with academic resistance. Professor Curp’s review does not adequately represent the textured arguments in “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World” or the chain of events that led to the creation of Israel. I hope that H-German members will take the time to read the book, which won the 2011 Sybil Halpern Milton Prize from the “German Studies Association”, and then make up their own minds about the impact of Nazi ideology on Islamism.