Counting the cost of patriotism on the Golan Heights

The Other Occupation

Getting to know the Golan

14 June 2011

Israel’s killing of dozens of pro-Palestinian demonstrators at the fence surrounding Majdal Shams has again catapulted the 19,000Druze and 2,000 Muslim Arabs of the Golan Heights to popular attention. Despite being as numerous as Israeli settlers, they lack equal rights and access to resources, as Arthur Neslen discovered in this feature, which was spiked by Jane’s Islamic Affairs Analyst.

****

Salman Fakhr al-Din winced as he pointed up at Mount Hermon. “When I was a child, I tried to climb the mountain so that I could touch the sky,” he said, “but now it is filled with mines and soldiers and if you tried you could be killed. This mountain used to be part of our lives but it has become something strange and terrible.” He still lives in its shadow, in the Druze heartland ofMajdal Shams.

Forty years after the war that slid the Golan peninsula into Israel’s hands, the territory under Salman’s feet had changed drastically. Since 1967, mines had killed 42 people and injured more than 80 in the Golan. Forty percent of the victims were children.

No figures exist for the exact locations, number or types of mines planted in the Golan, but they stretch over several kilometres. Reports by landmines NGOs note a lack of warnings and fencing around many minefields. Often they are situated near schools and houses. Residents complain that every year some are washed into their gardens and streets by rain and soil erosion.

Saleh Barah had never had any mines awareness lessons at school when, aged 13, he went to play in a yard beside his local restaurant. “I was with my friend when we saw something that looked like a brown cola bottle,” Saleh said. “I asked ‘What’s that?’ and he started to open it so I shouted ‘Give it to me!’ He threw it over and I caught it and tried to open it. A few seconds later, everything went black”.

When Saleh awoke in a Haifa hospital 20 days later, he had lost a leg, an arm beneath the elbow, and one eye. The authorities offered him no financial compensation, he said. Now 38, and a respected agricultural businessman in Majdal Shams, Saleh blamed the occupation for the mines which still littered nearby roads. “Our lives are not important to the Israelis,” he told me. “It’s the same as what happened in Lebanon.”

In a bid to raise awareness about landmines issue, Saleh refuses to wear prosthetic limbs. “I want others to know me as I am,” he said. “Also, this way when people see me, they ask ‘What happened to him?’ and they start to learn.”

But even knowledge of the risks does not outweigh the economic necessities of life. In June 2001, a 73-year-old shepherd from the village of Buq’ata was killed by a mine near Ain Al-Hamra. One of his sons had died in a mine accident there 14 years before.

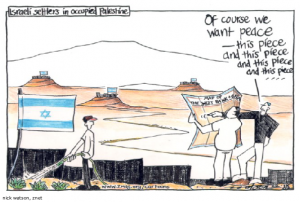

Syrian Golanis complain that the authorities turn a blind eye to such phenomena because it depresses their economic development and so helps Israel’s demographic battle. After the 2006 Lebanon War, settler leaders launched a slick $250,000 advertising campaign to double the Jewish population on the Golan within a decade.

The fertile volcanic fields and valleys of the Golan provide much of Israel’s fruit and wine industry but economic competition between the two communities is intense. While Syrian Golanis are said to provide around 30 percent of Israel’s apple crop, for instance, Israeli-Jewish moshavs and kibbutzim are thought to account for 40 percent.

Shahadi Nasrallah, a local agronomist blamed unequal distribution of water resources for the differential. “One dunam (1000 sq metres) of apple trees needs about 700 cubic metres of water a season to grow” he said, “but (the Israeli water company) Mekorot only allows Arab farmers about 200 cubic metres at best, while the Jewish farmers get as much as they need. If you don’t have enough water, your apple crop will be of a lower quality, and you will probably have to harvest it before it is ripe.”

On the macro-political level, Israel’s continued presence in the Golan is intimately tied to control of the region’s water resources. The Sea of Galilee, where Christians believe that Jesus fed the masses with fish and loaves, today accounts for around a third of Israel’s drinking water. Syria controlled its north eastern shore until 1967, but today exclusive access to the freshwater source is viewed as a national security issue in Tel Aviv.

Even the use of smaller local water resources, such as Lake Ram, has proved contentious. “It has seven million cubic metres of water – which Mekorot collects – but they sell four million to the Jews and only three million to us,” Shahadi said. “We are not allowed to pump from it even though it is between our fields and we used the water all the time before 1967.” By contrast, Shahadi’s organisation, Golan for Development claimed that settlers had water from the lake pumped directly into their fields, and paid three times less for it.

Folklore in Israel has it that Syrian Golanis silently benefit from Israeli governance, but Samer Safadi disagrees. A teacher sacked for ‘security reasons’ after marrying an anti-occupation activist, Samer complained of discriminatory allocation of teaching resources, kindergartens, electricity and even garbage disposal.

“We do have more work here,” she admitted, “and politically we have greater freedom because Syria is undemocratic and a one party state. But we are absolutely ready to sacrifice these benefits to return the Golan to Syria. You cannot weigh patriotism against economics. It is the highest value a person can have.”

Such sentiments are common on the streets of Majdal Shams but a less strident tone is increasingly heard among the plateaux’s middle class. According to Shahadi Nasrallah, times changed after the Soviet Union fell. “The world became less ideological,” he said, “and people became more open to Americanisation, to visitors with coloured hair coming here, to Madonna. They started to put themselves first and instead of struggling they earned money, built houses and bought cars.”

Some believe that Israel only allowed five Druze towns to remain in the Golan in 1967 – after destroying over 100 villages and expelling more than 100,000 Arabs – because of a perceived strain of cultural pragmatism. Popular prejudices have, perhaps unfairly, held that Israel exploited this alleged quality among its own Druze population in the years after 1948.

However, pragmatism can cut both ways. Sitting in his comfortable apartment, Shahadi noted wryly: “I have calculated it many times from an economic point of view, and we would be better off in Syria. The prices there are lower and with the same fields we could live better.” Many local people believe that demilitarisation and a change of sovereignty over the Golan’s settlements, tourist sites, farms and vineyards would create an economic powerhouse for Syria.

It would also address the most emotive issue for the Arabs of the Golan: family reunification. Women, children, and non-religious men in the Heights are forbidden to visit relatives in Syria and those who do are barred from returning.

In a scenario popularised by Eran Riklis’ 2004 film The Syrian Bride, Chazme Rosaini’s daughter Nadia has not been allowed to return to Majdal Shams since she travelled to Damascus in 1983 following her marriage to a Syrian cousin.

Chazme, a great grandmother with bright blue eyes that peep out from behind a traditional Druze head-covering, spoke with pathos about the separation. “Back in ’83, the occupation seemed so temporary and Nadia really thought it would end soon,” she said. “We had a family wedding party here and it snowed heavily the next day. We heard them walk out across the snow on their way to Quneitra and from there, the Red Cross bussed them to Damascus. Since then, we have only met twice in Jordan.”

Until the mid-1990s, even telephone calls to Syria were banned and Chazme and her daughter had to communicate by megaphone at the infamous Majdal Shams ‘shouting fence’, where families and friends once regularly gathered to bellow messages at each other. One local legend has it that some women had heart attacks while trying to make themselves understood to relatives across the wide expanse of no man’s land.

“It was messy and oppressive,” Chazme said. “But this is the ‘Nakba’ [catastrophe] of war, its misery and strangeness – to be separated from your own flesh and blood, unable to touch, see or talk to them for days on end.”

Links between the Palestinians of the West Bank and the Syrians of the Golan are strong. ‘Samir’, an activist who was imprisoned for several years after becoming involved in a Syrian information gathering cell, said he had since taken part in solidarity actions on the West Bank.

“We have a connection to the Palestinian struggle and we support them with whatever materials we can,” he told me. “We had our own Intifada in 1982 when Israel annexed the Golan Heights and tried to force us to become Israeli citizens. But this is not the West Bank and we don’t have the demography to sustain an Intifada every day. Still we will struggle until the Golan is liberated.”

In the mid-1980s, a small minority of activists in the Golan Heights turned to acts of violent resistance. Samir was not one of them and he remained optimistic that the Golan would be returned peacefully to Syria in the next decade. “It is a question of when, not if” he repeated in answer to many questions.

But with two thirds of Israelis telling pollsters they want to hang on to the Heights, and four decades of accumulated grievance bubbling like lava beneath the rocks, the future remains uncertain. When asked what might happen if hope for a peaceful solution faded, Samir frowned and looked up at the mountain. “In this case,” he said gently, “maybe people will take this other way to struggle.”