From left to right: why the Brits swapped sides on Israel

Communal childcare at an Israeli kibbutz in the 1950s. Many on the left admired the socialist ideals of the young state.

The UK’s pro-Israel lobby in context

By Tom Mills, Hilary Aked, Tom Griffin and David Miller, Open Democracy

December 02, 2013

The pro-Israel lobby is not only important in the US, but is a transnational phenomenon, fostered by transnational organisations – many headquartered in Israel – and funded in large part by transnational corporate actors.

While the taboo on discussing the Israel lobby was broken decisively by Mearsheimer and Walt in their ground-breaking 2007 study,[1] there has been relatively little discussion of the lobby in the UK and the rest of Europe.[2] In this article, we examine the history and current organisation of the UK’s pro-Israel lobby. This is important for a number of reasons. Not least because the lobby is a significant player in UK politics, helping to blunt campaigns for Palestinian human rights, shore up support for Israel, attack and marginalise critics (including Jewish critics) of Israel and insulate political elites from pressure to act against Israel’s misdeeds. The purpose here is to provide an historically informed picture and a corrective both to US-centric accounts and those that emphasise the lobby’s allegedly independent power. We illustrate that the pro-Israel lobby is not only important in the US, but is a transnational phenomenon, fostered by transnational organisations – many headquartered in Israel – and funded in large part by transnational corporate actors. Crucially, our account illustrates that the lobby is not an alien interloper, but is integrated into wider neoliberal and/or neoconservative networks, forming a fraction of the transnational power elite.

London has been described by the Israeli think-tank, the Reut Institute, as a ‘hub’ of ‘delegitimisation’. In the early 20th century, however, it was a major hub of Zionist state building. In 1917 the British government issued the infamous Balfour Declaration, signalling its support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This had been lobbied for by the leading political Zionist in the UK, the Manchester University academic Chaim Weizmann, who later became the first President of Israel. Weizmann worked with a close-knit trio of supporters; the Guardian journalist Harry Sacher and the businessmen Simon Marks and Israel Sieff, who together ran the quintessential British clothing retailer Marks & Spencer. Along with other leading Zionists, Weizmann and his disciple-benefactors established a host of organisations headquartered at a building on London’s Great Russell Street known simply as ‘77’. This cluster of organisations would later form the basis of a number of Israeli state institutions, as well as the heart of the UK’s pro-Israel lobby. It included the World Zionist Organisation, the Jewish Agency and Keren Hayesod (‘Foundation Fund’), all of which would later become Israel’s ‘national institutions’. Also based there were the English Zionist Federation, the Joint Palestine Appeal and the Jewish National Fund, which would remain UK organisations, whilst affiliated to the parent ‘national institutions’ in Israel.

Left, Simon Marks (seated on the left) and Israel Sieff. Right Harry Sacher, 1882-1971, Guardian journalist and on the executive of the World Zionist Organization. He married one of Marks’ sisters (and became a director of Marks and Spencer in 1932) while Sieff married another. Marks married Sieff’s sister.

Throughout this early period of Zionist state building, the Zionists remained a minority within Britain’s Jewish community, the most influential members of which were strongly opposed to the idea of a Jewish state. This changed in the years leading up to the Second World War when, as the Institute for Jewish Policy Research notes, ‘the organized Zionists, who were increasing in number, began a kind of long march through the Anglo-Jewish institutions, finally capturing the Board of Deputies of British Jews in 1939’, thus gaining control of the official representative body of the community.[3] As a result of this ‘Zionisation’, the Jewish State was woven into the fabric of communal life in Britain. One of its many political legacies is the fact that today one of the constitutional purposes of the Board of Deputies of British Jews is ‘to advance Israel’s security, welfare and standing’.[4]

During the period of Zionist ascendancy, the Zionist Federation – the umbrella organisation for the Zionist movement in the UK – became ‘a mass phenomenon’.[5] Its membership spanned a range of political tendencies, from the radically egalitarian kibbutz movement to the far right Revisionist Zionism that now dominates Israeli politics. Though some felt the Zionist Federation was obsolete following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, it soon found a new niche in public relations, political lobbying, cultural diplomacy and the promotion of aliyah (Jewish immigration to Israel).[6] The Board of Deputies undertook some similar activities and from the mid-1970s, both were assisted by Britain’s first pro-Israel PR outfit, the British-Israel Public Affairs Committee (BIPAC). BIPAC was originally set up as a privately funded ‘service organisation’ to co-ordinate pro-Israel public relations. According to the Jewish Chronicle, however, it outgrew its secondary role, a cause of some tension with the Zionist Federation and the Board of Deputies.[7] It was initially headed by the Zionist Federation chair Eric Moonman. Support came primarily from Michael Sacher,[8] vice-president of Marks & Spencer, president of the Joint Israel Appeal (Britain’s foremost Zionist fundraising body) and the son of the aforementioned Harry Sacher.

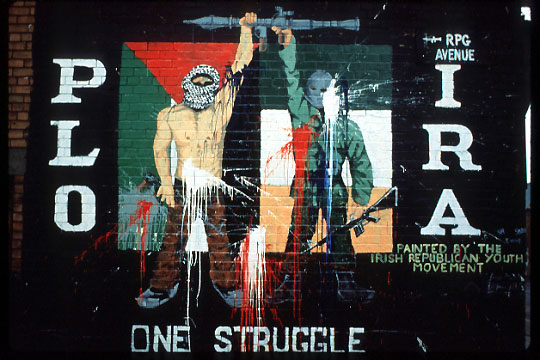

BIPAC’s establishment seems to have been a response to increasing pro-Palestinian activism in the UK, particularly at universities. In November 1977 Moonman, then a Labour MP, introduced a House of Commons debate about ‘racial prejudice on the university campus’ which followed the UN’s defining Zionism as racism in 1975.[9] A year later, BIPAC appointed Helen Silman – a former chair of the Israel Society at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS)[10] – as its head of research.[11] Silman, a convert to Judaism who later immigrated to Israel, had written a letter to the Jewish Chronicle in December 1975 lamenting the ‘pathetic Israeli propaganda and information service in the UK’ and complaining that ‘the PLO crusade’ at SOAS had ‘largely won the support of the young intellectuals’ at the college, with ‘the backing of the International Socialists’.[12] Support for Israel on the left was beginning to wane.

1970s UK: a time when young people on the Left were drawn to support violent struggles against colonial rule.

This was a period of social upheaval and economic and political crisis that saw a growth in popular egalitarian movements and anti-imperialist sentiment, as well as the emergence of a nascent, though increasingly potent, conservative backlash. These developments, along with a shift in Israeli politics following its annexation of the West Bank and the beginning of its intimate political relationship with with the United States, reshaped the politics of British Zionism.

Zionism shifts right

Since its foundation, Israel had been dominated by David Ben-Gurion’s left-wing Mapai party, which in 1968 was merged into the Israeli Labour Party. Mapai enjoyed good relations with the British labour movement, first through the British branch of Poale Zion and later via Labour Friends of Israel, which was established in 1957 to act ‘as a bridge linking Mapai… with the Labour Movement in Great Britain’.[13] Several leading British Zionists were affiliated with the Labour Party. Eric Moonman, as already noted, was a Labour MP, as was Barnett Janner, who chaired the Zionist Federation from 1940 and was President from 1950 to 1970. Though the Labour Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin was famously ambivalent, even hostile, towards Israel, by the 1950s the Labour Party was overwhelmingly supportive of Israel, which was imagined by many on the left to be a socialist state.

Barnett Janner, an immigrant from Lithuania, moved from Liberal to Labour to win a seat in Leicester at the 1945 election. He was President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, 1955-64. His son Greville won the seat when Barnett retired and he in turn became chairman of the BoD from 1978 to 1984.

The British left’s reflexive support for Israel gradually eroded from the late 1960s, and particularly following the 1973 war. At the same time, the Conservative Party, in thrall to the New Right, was coming to increasingly identify with Israel. Amongst the most pro-Israel of Tory MPs in this period, the historian William Rubinstein noted, were some of Britain’s most right-wing politicians; including Rhodes Boyson, Julian Amery, Winston Churchill, John Biggs-Davidson (Chairman of the right-wing Monday Club) and Ian Paisley.[14] In April 1979, the Jewish Chronicle quoted a ‘prominent Conservative close to Mrs Thatcher’ as saying: ‘Conservatives, particularly those of the younger generation, admire the State of Israel for its independence and power. They see the Jewish State as a vital outpost of the free world in the Middle East…’[15]

PM Margaret Thatcher attends the consecration of the new Woodside Park synagogue with Chief Rabbi Immanuel Jacobovits,

President of the United Synagogue Victor Lucas and others, April 1986. When she died, PM Netanyahu said she “was truly a great leader, a woman of principle, of determination, of conviction, of strength… a woman of greatness. She was a staunch friend of Israel and the Jewish people.”

This period saw the establishment of Conservative Friends of Israel, which was set up by the right-wing religious Zionist and Conservative politician Michael Fidler. Described by his biographer as having had extreme political views ‘reminiscent of the philosophy of Enoch Powell’, Fidler favoured arming the police and restoring capital punishment, and campaigned to ‘strictly enforce the Immigration Act’.[16] Over 80 MPs joined his Conservative Friends of Israel group in 1974, including Margaret Thatcher, and within a year it had a larger membership than Labour Friends of Israel.[17] By 1978 it was the largest political lobby in Westminster.[18] Fidler, its National Director, was also President of the General Zionist Organisation of Great Britain (GZO), which was established the same year as Conservative Friends of Israel as the British branch of the World Union of General Zionists, a deeply conservative Revisionist Zionist grouping.[19] In Israeli politics it was affiliated with the Liberal Party, which was part of the right-wing coalition led by Menachem Begin which came to power in 1977,[20] beginning a right-ward shift in Israeli politics which has continued largely unabated to this day. British Zionism soon followed suit when in 1980 the Revisionist Zionists ‘swept the board’ in elections to the Zionist Federation.[21]

Conservative PM David Cameron, guest speaker at the Conservative Friend of Israel annual business lunch 2012. “We promised to stand up for Israel and in Government that’s exactly what we’ve done”

Funding for Conservative Friends of Israel was raised mainly by Michael Sacher, the man behind BIPAC.[22] Other major donors included the multi-millionaire business tycoons Trevor Chinn, Gerald Ronson and Cyril Stein.[23] Stein, founder of the gambling company Ladbrokes, was also a major supporter of the Jewish National Fund. Whilst the mainstream of British Jewry supported the ‘peace process’ in the 1990s, he funded a Jewish settlement in the West Bank.[24] Trevor Chinn inherited his substantial wealth from his father, who owned the car company Lex Services and was President of the Jewish National Fund of Britain[25] as well as joint vice president of the Joint Palestine Appeal.[26] Like Stein, Chinn was also a major donor to Labour Friends of Israel and both men used their influence there to try and block movements towards peace.[27] Gerald Ronson is a close friend of Chinn’s[28] and the founder of the Community Security Trust, an organisation which exists ostensibly to protect the Jewish community in the UK from anti-Semitic violence, but has been criticised for a lack of transparency and accountability and for including critics of Israel in its operational definition of antisemitism.[29] Ronson also founded its forerunner, the Group Relations Educational Trust, in 1978 with support from Marcus Sieff, the chairman of Marks & Spencer.[30]

Neoliberal Zionism

Chinn, Ronson and Stein were part of a circle of wealthy British Zionists who bankrolled a number of pro-Israel organisations from the 1980s, but showed little interest in the traditional institutions of Jewish life. They came to be known as ‘the funding fathers’.[31] ‘Unelected and unaccountable,’ Geoffrey Alderman writes, they became ‘the new rulers of Anglo-Jewry’.[32] Most were affiliated with Britain’s foremost Zionist fundraising organisation, the Joint Israel Appeal (formerly the Joint Palestine Appeal, and later the United Jewish Israel Appeal). The Joint Israel Appeal was originally founded in 1944 by Simon Marks, and under the leadership of his nephew Michael Sacher it ‘established itself as the pre-eminent and most powerful single organization in the community’.[33] During the 1980s it was, the Jewish Chronicle reports, run by a ‘triumvirate’ of Trevor Chinn, Gerald Ronson and Michael Levy, and was ‘widely regarded as the community’s most influential organisation’.[34] Levy, a former record company executive and a relative newcomer to the ‘funding fathers’ circle, would later play a part in the rightward shift of the Labour Party under Tony Blair – and perhaps some role in the party’s rapprochement with Israel.

Tony Blair and Lord Levy

Levy was introduced to Blair by Gideon Meir, an official at the Israeli Embassy in London, and was later appointed Blair’s chief fundraiser. He became a key figure in a network of New Labour donors that allowed Blair to achieve financial independence from the trade unions and to build up a coterie of advisors – including Alastair Campbell and Jonathan Powell – who would follow him to 10 Downing Street. Trevor Chinn was one of the donors to Blair’s Labour Leader’s Office Fund, a blind trust for which Levy was, in press vernacular, the bagman.[35] Whether it was due to the direct influence of pro-Israel donors, or simply a feature of the Labour Party’s broader move to the right, is difficult to judge, but in 2001 the Labour Party power broker, lobbyist and former Labour Friends of Israel chair Jonathan Mendelsohn commented that: ‘Blair has attacked the anti-Israelism that had existed in the Labour Party… The milieu has changed. Zionism is pervasive in New Labour.’[36]

This Zionism though was distinct from the Labour Zionism that had dominated the Zionist Federation and the Labour Party a generation earlier. As the more established British Zionist organisations moved further to the right, becoming detached, to some extent, from elite opinion in the UK, they were eclipsed by a new generation of neoliberal Zionists, removed from Jewish communal life but deeply integrated into networks of corporate-state power and in many cases the transnational conservative movement. This network of businessmen and financiers now dominates the organisations that comprise the UK’s pro-Israel lobby. The most influential of these are the Jewish Leadership Council (JLC) and the Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre (BICOM), both of which were established after the collapse of the Oslo peace process and the outbreak of the second intifada. BICOM is the subject of our recent Spinwatch report, ‘Giving Peace a Chance?’. In it we note that while BICOM is embedded within the British Zionist movement, it distances itself from some of the more hard-line pro-Israel organisations. It has adopted a strategic approach to communications, employing public relations and lobbying professionals. Rather than targeting public opinion, it seeks to insulate policy-makers from the negative opinions about Israel encountered amongst the public.

The Jewish Leadership Council (JLC), with which BICOM is closely connected, was set up in 2003 by the then President of the Board of Deputies, Henry Grunwald. Grunwald was frustrated that though a number of wealthy Jewish businessmen were close to the Prime Minister, Blair had not met with any official representatives of the community since taking office.[37] This was quickly rectified. Within months of its launch members of the Jewish Leadership Council were invited to 10 Downing Street. Amongst the JLC’s key backers were the ‘funding fathers’ triumvirate, Trevor Chinn, Gerald Ronson and Michael Levy.[38]

The JLC incorporates representatives of a number of non-political charitable organisations, which is reflected in its broad remit covering religious, charitable and welfare activities. Pro-Israel lobbying, however, has always been an important part of its work. In December 2006 it established a non-charitable company, the Jewish Activities Committee, as a vehicle to handle political operations. The company’s founding directors were Trevor Chinn, Henry Grunwald, BICOM’s then vice chair Brian Kerner and BICOM’s chairman and main funder, the Finnish billionaire Poju Zabludowicz. That same month the JLC co-founded the Fair Play Campaign Group with the Board of Deputies, aiming ‘to coordinate activity against boycotts of Israel and other anti-Zionist campaigns’.[39] According to the JLC’s website, the Fair Play Campaign Group ‘acts as a coordinating hub’ and ‘keeps an eye out for hostile activity so it can be an early-warning system for pro-Israel organisations in the UK’.[40] Fair Play later launched the Stop the Boycott campaign with BICOM, with the Jewish Activities Committee acting as a vehicle for donations.

Brian Kerner and Mick Davis, leaders of various intersecting British Jewish and pro-Israeli groups at Bicom’s 2009 annual dinner held at the Berkeley Hotel in Knightsbridge. The event raised £800,000 for Bicom

The Jewish Leadership Council has been repeatedly criticised for its lack of transparency and accountability.[41] Indeed it would appear that a considerable motivation behind its establishment was to engage corporate elites as community representatives, ensuring access to policy makers whilst bypassing the Board of Deputies, which was seen as hampering effective lobbying operations. In May 2006, Brian Kerner told the Jewish Chronicle that the JLC was ‘meritocratic’ rather than democratic, representing ‘the strongest, toughest, most respected and most powerful leaders of the community’.[42] Kerner is one of a number of figures who straddle the organisations that make up the core of Britain’s pro-Israel lobby. He was chair of the United Jewish Israel Appeal from 1995 to 2000, vice chair of BICOM from 2001 to 2011 and is currently co-chair of the Fair Play Campaign Group and a council member of the JLC.[43] A comment he made to the Guardian following the outbreak of the second intifada gives an indication of his political perspective:

My own opinion has changed totally. I have gone from being leftwing to supporting a rightwing government. [Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud] Barak offered everything and got a kick in the head for doing so. By offering so much, it encouraged violence. The Palestinians respond to strength rather than anything perceived as weakness. … [Ariel Sharon] has not put a foot wrong so far. There has been restraint. I find it odd that I am now supporting a man a few months ago I would not have considered.

[44]

The second intifada was also a key turning point for many non-elite British Jews – but in the opposite direction:

Since the second intifada in 2000, traditional UK Jewish support for Israel had become increasingly difficult to maintain as more and more Jews saw Israeli intransigence as a contributing factor in the failure of Oslo. While at first such ‘dissidence’ from communal support for Israel was largely confined to the left… and groups that were, often unfairly, dismissed as comprising secular, uninvolved, marginal Jews – as the 2000s wore on, the consensus at the heart of the community also came under strain.[45]

As many liberals and leftists in the UK Jewish community grew increasingly uncomfortable with the escalating violence and rightward shift of Israeli politics, the ‘funding fathers’ sought to mobilise British Jews behind Israel. ‘Since the second intifada started’, writes the former Director of the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, ‘pro-Israel leaderships in Jewish communities urged Jews to close ranks and express complete solidarity with Israel. They tried to marginalise dissent, increasingly fostering a “for us or against us” mentality’.[46] This is the reality of the pro-Israel lobby today. As the Zionist dream loses what remains of its emancipatory sheen, and Israel’s violence and racism become impossible to ignore, an increasingly detached elite seeks to mobilise and constrain a reactionary base, whilst intimidating and silencing whose who speak out.

Continued support for pro-Israel organisations still rests to some extent on the dream of Jewish emancipation. But as the more the conservative character of the lobby becomes known, the more likely it is that liberals and progressives will abandon it, undermining its support base and thus its effectiveness in concealing, excusing or justifying Israeli human rights abuses. We hope that our account will help to foster such a state of affairs.

[1] John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

[2] Though see Peter Oborne and James Jones, ‘The pro-Israel lobby in Britain: full text’, OpenDemocracy, 13 November 2009. http://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/peter-oborne-james-jones/pro-israel-lobby-in-britain-full-text and David Cronin Europe’s Alliance with Israel: Aiding the Occupation, London: Pluto Press, 2010.

[3] Barry Kosmin, Antony Lerman and Jacqueline Goldberg, The attachment of British Jews to Israel, Institute for Jewish Policy Research Report No.5 November 1997, p.3.

[4] Board of Deputies Constitution Incorporating all amendments up to 21 September 2008, http://www.bod.org.uk/content/Constitution2008-09-21.pdf

[5] Stephan E. C. Wendehorst, British Jewry, Zionism, and the Jewish State, 1936-1956. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, p.266.

[6] Natan Aridan, Britain, Israel and Anglo-Jewry 1949-57. Routledge, 2004, p.223.

[7] ‘UK’s most effective lobby for Israel’, Jewish Chronicle, 28 August 1987, p.7.

[8] ‘BIPAC made impact’, Jewish Chronicle, 8 October 1976, p.6.

[9] HC Hansard 25 November 1977, Volume 939 Columns 2058-72

[10] ‘SOAS Arabists are ousted’, Jewish Chronicle, 21 March 1975, p.36.

[11] ‘Bipac research appointment’, Jewish Chronicle, 6 October 1978, p.9.

[12] ‘Anti-Zionism on campus’, Jewish Chronicle, 19 December 1975, p.17.

[13] Jewish Chronicle, 4 October 1957, front page.

[14] W. D. Rubinstein, The Left, the Right and the Jews. Worcester: Billing & Son, 1982, pp.153-4.

[15] Joseph Finklestone, ‘Election ‘79’, Jewish Chronicle, 27 April 1979, p.8.

[16] Bill Williams, Michael Fidler (1916-1989): A study in leadership. Stockport: R&D Graphics, 1997, p.315.

[17] Ibid., p.347.

[18] American Jewish Yearbook, 1980. p.199.

[19] Bill Williams, Michael Fidler (1916-1989): A study in leadership. Stockport: R&D Graphics, 1997, pp.361.

[20] ‘Independent Liberals Cut Ties with World Union of General Zionists’, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 16 July 1968.

[21] Bill Williams, Michael Fidler. 1916-1989): A study in leadership. Stockport: R&D Graphics, 1997, p.364.

[22] University of Southampton Library Archive, Papers of M.M.Fidler, 1943-88. MS 290 A1001/93, Michael Sacher letter to Hugh Fraser, 8 January 1982.

[23] University of Southampton Library Archive, Papers of M.M.Fidler, 1943-88. MS 290 A1001/45 Michael Fidler, letter to Peter Thomas, 1 November 1988.

[24] ‘Obituaries: Cyril Stein’, Telegraph.co.uk, 23 February 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/finance-obituaries/8343803/Cyril-Stein.html; Alex Renton, ‘UK link to extremist Israeli groups’, Evening Standard, 26 August 1998, p.2.

[25] ‘President of J.N.F. in Britain Honored at Dinner in London’, Jewish News Archive, 29 October 1963; ‘1 Million Trees to Be Planted in Honor of Prince and Queen of England’, Jewish News Archive, 18 May 1973.

[26] ‘News Brief’, Jewish News Archive, 24 October 1969.

[27] In 1990 Chinn and Stein withdrew their funding from Labour Friends of Israel in protest over the group’s decision to hold a joint meeting with the Middle East Council at the Labour Party conference that October. See ‘Israel’s friends make enemies’, The Times, 4 October 1990.

[28] Gerald Ronson and Jeffrey Robinson, Leading from the Front: My Story. Random House, 2009, p.124.

[29] Geoffrey Alderman, ‘Our unrepresentative security, Jewish Chronicle, 18 April 2011.

[30] Gerald Ronson and Jeffrey Robinson, Leading from the Front: My Story. Random House, 2009, p. 245.

[31] Geoffrey Alderman, Modern British Jewry, p.387.

[32] Ibid., p.388.

[33] Barry Kosmin, Antony Lerman and Jacqueline Goldberg, ‘The attachment of British Jews to Israel’, JPR Report No.5, 1997, http://www.jpr.org.uk/downloads/Attachment%20of%20Jews%20to%20Israel.pdf

[34] Simon Rocker, ‘Leadership Council elects executives’, TheJC.com, 2 March 2006.

[35] David Osler, Labour Party Plc: The Truth Behind New Labour As A Party Of Business, Mainstream Publishing, 2002, p.62.

[36] Quoted in Richard Allen Greene, ‘Jewish vote evenly split in Britain’, JTA, 8 May 2001. http://www.jta.org/news/article/2001/05/08/7796/.1021Jewishvoteevenlys

[37] The Jewish Leadership Council, About Us > Leadership http://www.thejlc.org/about-us/history/ [Accessed 13 April 2012]; Leon Symons, ‘Board anger on Blair talks’, TheJC.com, 5 March 2004.

[38] Simon Rocker, ‘Leadership Council elects executives’, TheJC.com, 2 March 2006.

[39] Fair Play Campaign group, http://www.fairplaycg.org.uk/ [Accessed 29 October 2012].

[40] Jewish Leadership Council, Fair Play Campaign group, http://www.thejlc.org/portfolio/fair-play-campaign-group/ [Accessed 24 October 2012].

[41] See for example Simon Rocker, ‘Board vice-president’s attack on JLC prompts open warfare’, TheJC.com, 23 February 2012.

[42] Simon Rocker, ‘So they say they’re in charge’, TheJC.com, 17 May 2006.

[43] Jewish Leadership Council, Brian Kerner, http://www.thejlc.org/author/bkerner/ [Accessed 15 November 2013].

[44] Ewen MacAskill and Brian Whitaker, ‘Barak’s failures lead all shades of British Jewry to trust in Sharon’, Guardian, 28 March 2001, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2001/mar/28/israel4

[45] Keith Kahn Harris, ‘The Dog That Didn’t Bark: Why the UK Jewish Community Supported Operation Pillar of Defence’, Jewish Quarterly – Winter 2012, p.23.

[46] Anthony Lerman, ‘Reflecting the reality of Jewish diversity’, guardian.co.uk, 6 February 2007, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2007/feb/06/holdjewishvoices8

David Miller is Professor of Sociology in the Department of Social and Policy Sciences at the University of Bath and co-director of Public Interest Investigations, a non-profit company which is responsible for Spinwatch.org and Powerbase.info.

Tom Griffin is a Ph.D researcher at the University of Bath and a freelance writer. He is a former Executive Editor of the Irish World.

Hilary Aked is a freelance writer and researcher, qualified journalist and doctoral candidate at the University of Bath. She had worked in the Occupied Territories and is researching the pro-Israel lobby in the UK.

Tom Mills is a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Bath and a co-editor of New Left Project

They are co-authors of The Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre: Giving peace a chance? (Public Interest Investigations 2013). They are grateful to Jamie Stern-Weiner for his research input and feedback on a draft of this article.

Crossposted with thanks to New Left Project.

Michael Levy and Tony Blair, The Independent, March 2006

Lord Levy: Labour’s fundraiser, BBC March 2007