Last chance saloon

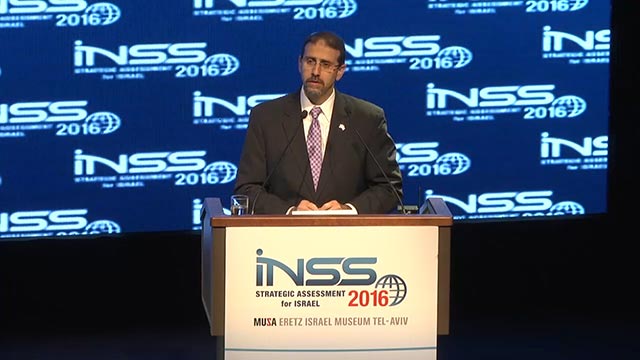

Giving fair warning: Dan Shapiro, US ambassador to Israel, tells the Institute for Strategic conference, Tel Aviv, January 2016:

[T]oo many attacks on Palestinians lack a vigorous investigation or response by Israeli authorities. Too much vigilantism goes unchecked, and at times there seems to be two standards of adherence to the rule of law – one for Israelis and another for Palestinians.

As Israel’s devoted friend and its most stalwart partner, we believe that Israel must develop stronger and more credible responses to questions about the rule of law in the West Bank.

In response former advisor to PM Netanyahu Aviv Bushinsky attacked him as “A little Jew boy” or “Yehudoni” in Hebrew.

How the U.S. came to abstain on a U.N. resolution condemning Israeli settlements

For the first time in 36 years, the U.N. Security Council passed a resolution critical of Israel’s Jewish settlements on Palestinian territory. The United States abstained.

By Karen DeYoung, Washington Post

December 28, 2016

On Dec. 21, amid his morning workout, an afternoon round of golf and a family dinner with friends, President Obama interrupted his Hawaii vacation to consult by phone with his top national security team in Washington. Egypt had introduced a resolution at the U.N. Security Council condemning Israeli settlements as illegal, and a vote was scheduled for the next day.

The idea had been circulating at the council for months, but the abrupt timing was a surprise. Obama was open to abstaining, he said on the call, provided the measure was “balanced” in its censure of terrorism and Palestinian violence and there were no last-minute changes in the text.

Sceptics, including Vice President Biden, warned of fierce backlash in Congress and in Israel itself. But most agreed that the time had come to take a stand. The rapid increase of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, despite escalating U.S. criticism, could very well close the door to any hope of negotiating side-by-side Israeli and Palestinian states. Pending Israeli legislation would retroactively legalize settlements already constructed on Palestinian land.

The resolution’s sponsors, four countries in addition to Egypt, were determined to call a vote before Obama left office. A U.S. veto would not only imply approval of Israeli actions but also likely take Israel off the hook for at least the next four years during President-elect Donald Trump’s administration.

“People debated whether the backlash to the vote, if we abstained, would do more harm than good, that it would reverberate into our politics, into Israeli politics, and would accelerate trends,” a senior administration official said. But “every potential argument about making things worse is already happening.”

Israel had been a third rail of U.S. political debate for decades, but Obama, aides noted, never had to run for office again. He had nothing to lose.

When the vote finally came two days later, all but one of the Security Council’s 15 members, including Russia, China and the United States’ closest European allies, approved it. U.S. Ambassador Samantha Power, who had just received the go-ahead from Obama, via a call from White House national security adviser Susan E. Rice, raised her hand high in abstention. The resolution was approved.

Reaction was as predicted. Members of Congress charged that Obama had undercut one of the United States’ closest allies. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the measure “absurd,” and his government said the United States had secretly “colluded” with the Palestinians on the resolution — a charge Obama aides heatedly denied.

Trump, who had publicly urged a veto, tweeted for Israel to “stay strong” until his inauguration. Trump clearly plans a sharp change of course in U.S. policy. Chief Trump strategist Stephen K. Bannon and others close to the president-elect have grown increasingly unhappy with administration comments in recent weeks, especially on Israel. Bannon and Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, are leading the president-elect’s efforts on the Israel debate during the transition, fielding calls from Israeli officials and allies, and arranging meetings, according to several people familiar with the internal setup.

Asked by reporters Wednesday whether he thinks the United States should leave the United Nations, Trump said that as long as the international body is “solving problems” rather than causing them, “if it lives up to its potential, it’s a great thing. If it doesn’t, it’s a waste of time.”

But for the moment, at least, according to senior Obama administration officials who discussed the road to the president’s decision on the condition of anonymity, the administration takes some satisfaction in that the issue of settlements and the perceived risk they pose to an eventual Israeli-Palestinian peace deal is back on the international agenda.

The first public hint of the move came in the heat of the U.S. presidential campaign in September, just after nominees Trump and Hillary Clinton held meetings with Netanyahu in New York. In an Israeli television interview, Dan Shapiro, U.S. ambassador to Israel, said Obama was “asking himself” about the best way to promote a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Shapiro said,

This could be a statement we make or a resolution or an initiative at the U.N. . . . which contributes to an effort to be continued by the next administrationLasts chance saloomn.

Shapiro clearly anticipated a Clinton victory, reflecting thinking within the administration that if Obama took the heat for a critical statement or resolution, she would be in a better position to play the “good cop” and move Israel toward substantive negotiations. For her part, Clinton had expressed no interest in a resolution.

The United States had long declined to join much of the rest of the world in defining as “illegal” the building of Israeli housing in the West Bank and majority-Palestinian East Jerusalem. The final decision on who had the rights to what land was to be negotiated, according to decades of international agreements by Israelis and Palestinians.

During his eight years in office, Obama had tried to kick-start direct Israeli-Palestinian talks over a “final status” accord, including with nearly two years of intensive negotiations by Secretary of State John F. Kerry. Throughout that time, the administration had avoided Security Council action on the issue, persuading sponsors to withdraw potential resolutions before a vote.

The Palestinians were always lobbying for a vote, although the administration considered most of the proposed resolutions too one-sided. At the same time, the administration’s thinking was that there was no point in pre-empting talks if there were still a realistic chance of getting the parties back to the table.

But with settlements rapidly expanding, and senior officials in Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition saying the two-state solution was effectively dead, other Security Council members were agitating for a new resolution, and the administration was listening.

So was Netanyahu’s government, which picked up immediately on Shapiro’s comments.

Trump’s Nov. 8 victory increased Israeli concern of a pre-emptive move by Obama, along with determination by other U.N. members to table a resolution before the new U.S. administration took office.

The Palestinians and Egypt — which currently holds the rotating Arab seat on the Security Council — had been talking up a new resolution on settlements since the summer. At the same time, New Zealand, which had withheld a previous measure at the United States’ request, had written a new draft.

Both versions began to circulate in early December. The United States, in discussions with New Zealand and indirectly with Egypt, insisted it would not even consider the matter unless the resolutions were more balanced to reflect criticism of Palestinian violence along with condemnation of Israeli settlements, according to U.S. officials.

The officials categorically denied Israeli allegations this week that the United States secretly pushed the resolutions. An Egyptian newspaper report alleging that Rice and Kerry met in early December with Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat and the head of Palestinian intelligence to plot the resolution was false, officials said. While Kerry and Rice met separately with Erekat during a visit here, they said, there was no intelligence official and no discussion of a resolution.

The officials also denied that Biden, in two mid-December calls to Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, had urged a “yes” vote in the council. Biden, who handles the Ukraine account for the White House, calls Poroshenko several times a month, and those times were supporting the proposed nationalization of a corrupt bank.

The Egyptian draft, tweaked with help from Britain, was submitted to the council on Dec. 21. As often happens when competing and overlapping resolutions circulate, New Zealand and co-sponsors Malaysia, Senegal and Venezuela decided to drop their version and support the nearly identical Egyptian resolution in order to cut short prolonged negotiations and push for a vote.

“The United States did not draft or originate this resolution. Nor did we put it forward,” Kerry said in a speech Wednesday. “It was drafted by Egypt . . . which is one of Israel’s closest friends in the region, in coordination with the Palestinians and others.”

The final text was carefully drawn to use identical, or near-identical, language to resolutions dating to the 1970s on Israel and the Palestinians that the United States had previously approved.

I didn’t see the U.S. play any role at all

“We wanted to see Security Council action,” said a diplomat from one of the sponsors. “We wanted the international community to reaffirm the two-state solution.”

“We wanted to do it; it’s a very important issue for us,” said another diplomat, who said there had been “no conversation” with the United States about the subject. “I didn’t see the U.S. play any role at all.”

In the meantime, however, Egypt came under sharp pressure from Israel — which frequently supports U.S. military aid to Cairo — and from Trump, who called Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi. Arab foreign ministers convened a Thursday meeting in Cairo, and by midday, Egypt had withdrawn its resolution. A scheduled 3 p.m. vote was cancelled.

Under Security Council rules, co-sponsors can still put the resolution forward, which is what New Zealand and the others did Friday, when the council reconvened for a vote.

At the time, according to several diplomats, few — if any — knew how the United States would vote.

Carol Morello and Robert Costa contributed to this report.