Historic error of claims of great rise in antisemitism

The inset on advertisements attacking Jew-haters has been inserted by JfJfP postings.

Last summer, the web was awash with articles headed “rise of antisemitism in Europe” Click on them to find what photos they used and they were almost invariably of demonstrations against Operation Protective Edge and the assault on Gaza. This one, of a Berlin protest, was used in the Washington Post under the heading Anti-Jewish slogans return to the streets in Germany as Mideast protests sweep Europe. If, as Brian Klug argues, the figure of ‘the Jew’ is essential to antisemitic discourse then surely the figure of the Jew-hater is essential to the claims of rising antisemitism.

Does Moral Opposition to ‘Operation Protective Edge’ Translate into Antisemitism?

By Brian Klug, The Critique

April 01, 2015

I. Introduction

The Gaza Strip has been under military occupation by the State of Israel since 1967. On 8 July 2014 the Israel Defence Forces launched ‘Operation Protective Edge’, a bombing campaign and ground incursion against Gaza, which continued until a ceasefire was announced on 26 August. The operation was aimed especially at Hamas, Islamic Jihad and other militant groups that were firing rockets and mortars into Israel from Gaza. While the exact figures are uncertain, there is no doubt that the vast majority of overall fatalities were Gazans, including approximately 500 children.[1] Around 20,000 homes in Gaza were “heavily damaged or destroyed”.[2] Gaza’s infrastructure was “crippled”.[3] By any measure, this was an asymmetric conflict.

As on previous occasions, there were large public demonstrations of protest against Israel in the streets of cities in Europe and elsewhere. By and large, they were expressions of moral outrage at what the protestors saw as the injustice of Israel’s military operation and continued occupation of Palestinian territories, combined with humanitarian concern at the scale of human suffering in Gaza.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=267o6wS6s0A&feature=youtu.be

During this period, numerous individuals, groups and monitoring agencies reported a substantial increase in Europe in the number of threats, attacks or invective directed at Jews in general in the wake of ‘Operation Protective Edge’. Some of these incidents were said to have taken place at the demonstrations themselves. A typical headline reflecting this development appeared in the British newspaper the Guardian on 7 August 2014: ‘Antisemitism on rise across Europe “in worst times since the Nazis”’.[4] A key sentence in the article says, “Across Europe, the conflict in Gaza is breathing new life into some very old, and very ugly, demons.”

If we take all this at face value it seems to indicate that the price of moral opposition to ‘Operation Protective Edge’ [See Frowe, Hosein & Almotahari on the ethics of the Gaza War] has been an increase in antisemitism and a return to the bad old days when life for Jews in Europe was constantly under threat.

The evidence for this view, however, is complex in at least three ways: historical, factual and conceptual. The reference to ‘the Nazis’ in the Guardian headline invites us to view the current situation through the lens of another era: Europe before and during the Second World War. But is this the right historical frame for understanding the facts today? And what are the facts exactly? Do they support the assertion that antisemitism is on the rise? Furthermore, is ‘antisemitism’ the right way to characterise the (majority of) the evidence? Or do we need to conceptualise it differently?

In a short article it is not possible to do justice to the issues raised by these three kinds of complexity. My limited aim is to problematize the view that the moral protests against ‘Operation Protective Edge’ have contributed to the return of antisemitism.

In the spirit of The Critique as a philosophical website, I shall focus on conceptual questions, especially the concept of antisemitism. However, as the three kinds of complexity that I have mentioned are interconnected, I shall bring certain factual or empirical questions into the discussion and I shall close with some critical observations about the historical frame that the very word ‘antisemitism’ suggests.

II. Perception and reality

The Guardian article that I have cited (which is representative of much of the reporting on this subject in a variety of mainstream media) begins by giving instances where European protest against Israel’s actions in Gaza has taken an antisemitic form. After quoting a number of sources who express alarm at this “anti-Jewish backlash”, the article comments: “Studies suggest that antisemitism may indeed be mounting”. This claim is supported by a survey conducted in 2012, two years prior to ‘Operation Protective Edge’, by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA).[5] But what exactly does this survey show?

The FRA report presents the results of an open online survey of 5,847 people in eight European Union (EU) countries where about 90% of the estimated Jewish population in the EU live: Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Sweden and the United Kingdom (UK). The survey was open to individuals 16 years or older who live in the selected countries and who identify as Jewish. For the most part, the questionnaire was quantitative, though at the end respondents could add comments in their own words.

The picture that emerges from this survey is certainly troubling. “Two thirds of the respondents (66%) consider antisemitism to be ‘a very big’ or ‘a fairly big problem’ in the country where they live” (p. 15). 76% “consider that antisemitism has worsened over the past five years in the country where they live” (p. 16). Overall, 75% “consider antisemitism online as a problem today in the country where they live” (p. 19), while 73% “perceive that antisemitism online has increased over the last five years” (p. 20). 59% “feel that antisemitism in the media is ‘a very big’ or ‘a fairly big problem’, while 54% say the same about expressions of hostility towards Jews in the street and other public places” (p. 19). 46% “worry about becoming a victim of an antisemitic verbal insult or harassment in the next 12 months, while one third (33%) worry about being physically attacked in that same period” (p. 32).

The picture that emerges is troubling because it shows that many Jews in Europe are not living with the peace of mind and sense of security that every ethnic and religious group ought to enjoy. It is troubling also because there is bound to be some basis in reality for this state of affairs. Nor is this news: no one with a sense of history can doubt that the well of antisemitism runs deep in Europe and only the naïve will think that the well has run dry.

However, the statistics I have quoted from the report are about what the survey respondents “consider”, “perceive”, “feel” and “worry about”. It is not possible on this basis alone to infer the extent to which antisemitism exists in Europe, nor is it possible to determine the degree to which it has – or has not – changed for the worse. This is not a criticism of the survey. It is only to say that the FRA survey does not support the claim that “antisemitism may indeed be mounting”.

The picture that emerges is troubling because it shows that many Jews in Europe are not living with the peace of mind and sense of security that every ethnic and religious group ought to enjoy. It is troubling also because there is bound to be some basis in reality for this state of affairs

Furthermore, the focus on perception introduces a large element of subjectivity. What, for example, counts as an antisemitic view or comment? Question B15b gives a list of eight potentially offensive statements.[6] It includes the statement “Israelis behave ‘like Nazis’ towards the Palestinians”. In the opinion of 81% of respondents, a non-Jew who says this is antisemitic (p. 23). Question B17 gives a list of six possible views or actions by non-Jews. It includes “Supports boycotts of Israeli goods/products” and “Criticises Israel”. These were considered antisemitic by 72% and 34% of respondents respectively (p. 27).[7] So, where others see a straightforward moral or political position on Israel (with which they might or might not agree), these respondents see antisemitism.[8]

Recent crime statistics for London seem, at first sight, to lend support for the claim that “antisemitism may indeed be mounting”, at least in the capital city. Figures compiled by the Metropolitan Police Service (‘the Met’) for “Anti-Semitic crime” in London between December 2013 and December 2014, a period that includes the duration of ‘Operation Protective Edge’, show an increase of 83.3%.[9]

But what is an ‘Antisemitic crime’? The Met give this definition: “An Anti-Semitic Offence is any offence which is perceived to be Anti-Semitic by the victim or any other person, that is intended to impact upon those known or perceived to be Jewish.”[10] In other words, reality is what you perceive it to be.

Sir William Macpherson

Sir William Macpherson

His ruling that if a victim thinks an attack is racist the police should investigate it as such. Should it apply to all ethnic groups?

This seems a curious metaphysical position for the hard-headed London police force to take. But it becomes comprehensible against the background of the Macpherson Report (1999) on the official inquiry into how the police handled the murder of the black London teenager Stephen Lawrence.

Among Macpherson’s recommendations was the following definition: “A racist incident is any incident which is perceived to be racist by the victim or any other person.”[11] Macpherson was struck by the failure of the police to investigate when they receive complaints that a racist crime has been committed. His intention, as I understand it, was to say something like this: where a person perceives that a racist crime has been committed then the police ought to treat the incident as a racist incident and investigate it accordingly.

Unfortunately, his definition of a racist incident has been taken out of context and has taken on a life of its own in the UK; hence the Met’s definition of ‘Anti-Semitic crime’. But to take the definition out of context is to take the content out of the definition.

Outside of Bishop Berkeley, perception does not define reality (and even his position is more sophisticated than this). If we perceive an incident to be antisemitic then the word ‘antisemitic’ must mean something more than ‘being perceived to be antisemitic’ or it means nothing. Not even a philosopher would come up with such an empty definition; except perhaps for the greatest egghead of all, Humpty Dumpty. When Alice queried his idiosyncratic use of language, Dr Dumpty famously replied: “‘When I use a word … it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.’”[12] In reality, we choose our words, not their meaning – or we end up with egg on our face.

Outside of Bishop Berkeley, perception does not define reality. If we perceive an incident to be antisemitic then the word ‘antisemitic’ must mean something more than ‘being perceived to be antisemitic’ or it means nothing

III. Word and meaning

What does the word ‘antisemitism’ mean? It is tempting to see its meaning as a function of the component parts of the word as such: the prefix ‘anti’ plus the substantive ‘Semitism’.[13] But, as Wittgenstein points out over and again, a word is not always the best guide to its own meaning. “For a large class of cases,” he says, “… the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”[14] ‘Antisemitism’ falls into this class: never mind the etymology, look at the use.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein

“For a large class of cases (…) the meaning of a word is its use in the language”

The German word Antisemitismus, which was coined in the second half of the nineteenth century, was intended to mark a departure from the old hatred of Jews, Judenhass. The new term was a fancy word for a secular idea that supposedly reflected modern science, especially the (so-called) science of race. Racial ideas were fundamental for the völkisch nationalism that was on the rise at the time (and which led to Nazism).

Over time, the word ‘antisemitism’, as words are wont to do, grew away from its initial moorings, so that today the concept is not tied to a biologically-based conception of Jewish identity and a political movement rooted in a racial ideology. Today antisemitism is aimed at Jews whether they are seen as a people, a nation, an ethnic group, a cultural group, a religious community, a class, a race or whatever. But the meaning of the word – ‘its use in the language’ – evolved from its roots and retains a semantic connection to them.

At the heart of its use is the figure of ‘the Jew’, a preconceived idea of what being Jewish consists in. This figure is essentially a figment or fiction. I say ‘essentially’ because it can, of course, happen that there are real people who are both Jewish and resemble the figure of ‘the Jew’. But this does not make the figure any more real: it merely muddies the waters by imparting an empirical sheen to the stereotype. In this regard (and others), antisemitism conforms to the logic of racism in general. The antisemitic stereotype is a frozen image projected onto the screen of a living person. The fact that the image might on occasion fit the reality does not affect its status as image. The image, so to speak, fastens onto the reality: it uses the reality to proclaim itself falsely as real.

The set of traits that constitute the figure of ‘the Jew’ typically includes such qualities as these: belonging to a sinister group that seeks its own collective advantage at the expense of everyone else and, moreover, possesses a mysterious power over governments and the media; loving money and seeking profit; being cunning and conniving, rootless and parasitic, legalistic and arrogant; and so on.

The set of traits is open-ended: new traits might be added while others drop out. But (to borrow again from Wittgenstein) there is a family resemblance between the different instances that hold the concept together. This is how concepts in general work: they work, in Wittgenstein’s analogy, like a length of rope whose strength “does not reside in the fact that some one fibre runs through its whole length, but in the overlapping of many fibres”.[15] So, on the one hand, the concept of antisemitism is elastic; on the other hand, its elasticity is not infinite. It does, after all, mean something.

IV. Facts and figures

With this analysis of the concept in mind, we can derive a rough and ready rule: hostility to Israel and Zionism are antisemitic when the figure of ‘the Jew’ is projected onto Israel because Israel is a Jewish state or onto Zionism because Zionism is a Jewish movement. Sometimes this is obvious and open. At other times it is either concealed or a matter of interpretation in the light of available evidence.

What light does this shed on the evidence – the facts and figures – that seem to suggest that moral protest against ‘Operation Protective Edge’ has contributed to the return of antisemitism? To begin with, the evidence is sometimes conflicting. Even the basic facts can be in dispute. A case in point is the widely-reported incident at the Synagogue de la Roquette during a march against Israel’s actions in Gaza.

A feature article in Newsweek opened with this account: “The mob howled for vengeance, the missiles raining down on the synagogue walls as the worshippers huddled inside. It was a scene from Europe in the 1930s – except this was eastern Paris on the evening of July 13th, 2014.”[16]

Members of the French Jewish Defence League and French police prepare to attack Muslims near the synagogue/ defend the synagogue from a Muslim mob. Photo from JTA.

But there is another version of these events which puts a completely different complexion on what happened. In this alternative version, Serge Benhaim, the President of the Synagogue, said afterwards, “Not one projectile was launched towards the synagogue. At no time were we put in danger.”[17] In this alternative account, members of the Ligue de Défense Juive (Jewish Defence League) deliberately provoked a mêlée.[18] France 24, noting that “both sides accuse each other of having lit the fuse”, posed the question: ‘What really happened?’[19] They did not give a definitive answer.

Hostility to Israel and Zionism are antisemitic when the figure of ‘the Jew’ is projected onto Israel because Israel is a Jewish state or onto Zionism because Zionism is a Jewish movement

As for the figures on antisemitism, social statistics are notoriously problematic, either due to the methodology used in compiling them or because of the different constructions that can be put upon them. So, for example, the Pew Research Center has just published the sixth in a series of reports analysing (among other things) ‘social hostilities’ towards religious minorities in countries across the globe.[20] Their finding regarding Jews is certainly worrying: “In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the number of countries where Jews were harassed. In 2013, harassment of Jews … was found in 77 countries (39%) – a seven year high””.[21]

The Jewish Daily Forward reports this finding this way: “Global antisemitic incidents reached a seven-year high”.[22] But the finding concerns the number of countries, not the number of incidents. These are independent variables: the number of countries could increase while the number of incidents decline, or vice versa. Furthermore, the primary sources used by the Pew study are reports from other bodies, whose own figures reflect a variety of monitoring practices. No account is taken of the possibility that these figures reflect an increase in reporting rather than an increase in incidents. And so on.

More fundamentally, The Jewish Daily Forward applies the word ‘antisemitic’ to the Pew report findings. But this is not how the report itself classifies these findings. Which brings us to the heart of the question and the light shed by applying the rule we derived from the concept of antisemitism.

V. Then and now

A recent official Parliamentary report in Britain commented that “undoubtedly spikes in tension in the Middle East lead to an increase in antisemitic events”.[23] This statement faithfully reflects the findings of various monitoring agencies that there is a correlation between conflicts in the Middle East involving Israel and a rise in the number of anti-Jewish incidents elsewhere in the world. Last year’s military campaign in Gaza was no exception. But should all these incidents be lumped together as ‘antisemitic’? Granted, for the sake of argument, that the figures are correct, does it follow that moral opposition to ‘Operation Protective Edge’ translated into antisemitism?

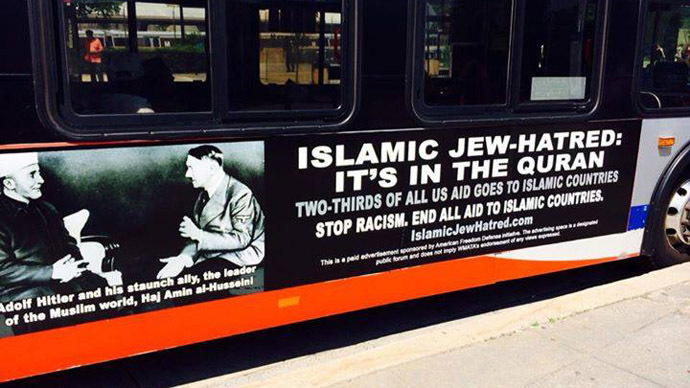

Ads on buses in Washington DC, 2014.The ads, which are to run until mid-June, were placed by the American Freedom Defence Initiative (AFDI), a self-proclaimed human rights group with has been accused of being an anti-Islam hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Centre and the Anti-Defamation League.

The AFDI says their ads are “response to the vicious Jew-hating ads that American Muslims for Palestine (AMP) unleashed on Washington, DC, Metro buses last month.”

The ads in question, which bore an image of US personification Uncle Sam with an Israeli flag in hand, were placed around the DC area on April 15 – tax day.

“We’re sweating April 15 so Israelis don’t have to! Stop US aid to Israel’s occupation!” the ad by the Illinois-based pro-Palestinian group read.

Dr. Osama Abu Irshaid, a board member for AMP, said that during tough economic times when Americans were struggling to pay their taxes, “our hard-earned money is going to a country that has implemented the last and longest-lasting military occupation in the modern world.”

At the beginning I cited an article in the Guardian and singled out this sentence: “Across Europe, the conflict in Gaza is breathing new life into some very old, and very ugly, demons.” To some extent this is true: some of the anti-Israeli reaction to the conflict in Gaza does take the form of projecting onto Israel the figure of ‘the Jew’; thereby it is antisemitic. Moreover, some of the “anti-Jewish backlash” reported in the article takes the form of projecting onto Jewish individuals, groups and institutions the same figure of ‘the Jew’ on account of Israel’s actions; and is antisemitic for this reason. But there is another element that is not the expression of demons that are very old and ugly but the product of an ethno-religious conflict, relatively new and decidedly ugly, between Israeli Jew and Palestinian Arab. Both sides have their partisan supporters; and this leads to clashes in the cities of Europe and elsewhere. In a way, the battle on the streets of Paris between pro-Palestinian protestors and members of the Jewish Defence League is a model for understanding the new hostility.

The point can be put this way. On the one hand, there is a form of hostility to Israel that derives from bigotry about Jews. On the other hand, there is a form of bigotry about Jews that derives from hostility to Israel. The two phenomena overlap and interact but they are different; in a way, they are opposites. Calling the second phenomenon ‘antisemitism’ does not help us understand either its nature or its provenance. Wittgenstein wrote, “Say what you choose, so long as it does not prevent you from seeing the facts.”[24] Ignoring the distinction between these two phenomena, applying the word ‘antisemitism’ across the board to all anti-Jewish hostility today, prevents us from seeing the facts.

This is partly because of the baggage that the word carries. Recall the headline of the Guardian article: ‘Antisemitism on rise across Europe “in worst times since the Nazis”’. The tendency of this headline is to collapse the present into the past, as if history were beginning to repeat itself. But it is not – not if this means that Jews today are faced by a threat of the same kind that they faced in the 1930s and 1940s. The situation of Jews in Europe (and the wider world) was dominated by the power of Nazi Germany, a state that was antisemitic to the core of its ideology and which was bent on destruction of Jewish life everywhere; a state whose hostility to Jews was ultimately genocidal.

Likening antisemitism today to that in Nazi Germany is peculiarly absurd, Antisemitism was state policy in Germany and enforced by the Gestapo (above) and other state paramilitary forces. The whole judicial system, from police officer to top judges had been Nazified so there was no recourse to the law for Jews, or any other group persecuted by the state.

That was then. The situation now of Jews in much of the world is dominated not by an anti-Jewish state but by a Jewish state; not by policies and actions that are directed against Jewish interests but in the name of those interests; and not by a hostile power (Germany) that occupies the lands where Jews live but by a friendly power (Israel) that occupies territory where others live.

On the one hand, there is a form of hostility to Israel that derives from bigotry about Jews. On the other hand, there is a form of bigotry about Jews that derives from hostility to Israel. The two phenomena overlap and interact but they are different; in a way, they are opposites

The Jewish divide over Israel is growing. But mainstream Jewish opinion around the world tends to rally in support of the state, defending actions like ‘Operation Protective Edge’, putting group or ethnic loyalty before a commitment to justice and human rights. This does not justify a single act, antisemitic or otherwise, directed against Jews as Jews. But it does help explain why these acts are increasing. Arguably, it is not so much the moral opposition to ‘Operation Protective Edge’ that translates into anti-Jewish hostility as the moral support that many Jews choose to give to a patently unjust military action carried out in their name. It can be argued both ways. The question is complex. It calls for careful and honest analysis.

This article is part of The Critique’s exclusive “The Great War Series Part I: Gaza, Isis and The Ukraine“. Follow The Critique on Facebook and Twitter @dekritik for more special features.

Footnotes and References:

[1] ‘Gaza crisis: Toll of operations in Gaza’, BBC News, 1 September 2014, available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-28439404 (viewed 25 February 2015).

[2] ‘UN chief: Gaza destruction “beyond description,” worse than last year’, Haaretz , 14 October 2014, available at http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/.premium-1.620698 (viewed 25 February 2015).

[3] ‘Gaza’s infrastructure crippled by conflict’, BBC News, 19 August 2014, available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-28850510 (viewed 25 February 2015).

[4] Jon Henley, ‘Antisemitism on rise across Europe “in worst times since the Nazis”, Guardian, 7 August 2014,available at http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/aug/07/antisemitism-rise-europe-worst-since-nazis (viewed 24 February 2015).

[5] FRA, Discrimination and hate crime against Jews in EU Member States: experiences and perceptions of antisemitism, November 2013, available at http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2013-discrimination-hate-crime-against-jews-eu-member-states_en.pdf (viewed 25 February 2015).

[6] The survey questionnaire is included as annex 1 in the Technical Report accompanying the FRA survey.

[7] In all three cases, the percentage scores combines two affirmative responses: “Yes, definitely” and “Yes, probably”.

[8] This analysis of the FRA report is adapted from my article ‘Antisemitism and the Jewish future in Europe’, published in Reviews and Critical Commentary,Council for European Studies, Columbia University, 10 December 2013, available at http://councilforeuropeanstudies.org/critcom/anti-semitism-and-the-jewish-future-in-europe/ (viewed 25 February 2015).

[9] Available at http://www.met.police.uk/crimefigures/textonly_month.htm (viewed 25 February 2015).

[10] Available at http://www.met.police.uk/crimefigures/textonly_month.htm#c40 (viewed 25 February 2015).

[11] Sir William Macpherson of Cluny, The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, London: HMSO, 1999, p. 328.

[12] Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass, chapter 6.

[13] The word could also be looked at as a combination of two affixes, ‘anti’ and ‘ism’, plus the stem, ‘Semite’; it comes to the same thing.

[14] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell, 1958, p. 20, par. 43.

[15] Philosophical Investigations, p. 32, par. 67.

[16] Adam LeBor, ‘Exodus: Why Europe’s Jews are fleeing once again’, Newsweek, 29 July 2014, available at http://www.newsweek.com/2014/08/08/exodus-why-europes-jews-are-fleeing-once-again-261854.html (viewed 28 February 2015).

[17] Richard Seymour, ‘The anti-Zionism of fools’, Jacobin, available at https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/08/the-anti-zionism-of-fools/ (viewed 28 February 2015).

[18] See also Nabila Ramdani, ‘False reports on Roquette Synagogue “attack” should be rectified’, Middle East Monitor, available at https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/articles/middle-east/13298-false-reports-on-roquette-synagogue-attack-should-be-rectified (viwed 28 February 2015).

[19] ‘Que s’est-il vraiment passé rue de la Roquette le 13 juillet?’, France 24, available at http://www.france24.com/fr/20140716-emeutes-rue-roquette-synagogue-paris-antisemitisme-conflit-isra%C3%A9lo-palestinien/ (viewed 28 February 2015).

[20] Pew Research Centre, Latest Trends in Religious Restrictions and Hostilities, 26 February 2015, available for download at http://www.pewforum.org/2015/02/26/religious-hostilities/ (viewed 28 February 2015).

[21] Ibid., p. 5.

[22] ‘Ant-Semitism hits 7-year high worldwide’, The Jewish Daily Forward, available at http://forward.com/articles/215583/anti-semitism-hits–year-high-worldwide/ (viewed 28 February 2015).

[23] Report of the All-Party Parliamentary Inquiry into Antisemitism, February 2015, p. 6, available for download at http://www.antisemitism.org.uk/ (viewed 28 February 2015).

[24] Philosophical Investigations, p. 57, par. 79.

Brian Klug is Senior Research Fellow in Philosophy, St Benet’s Hall, Oxford and a member of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Oxford. He is also Honorary Research Fellow, Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations, University of Southampton and Associate Editor, Patterns of Prejudice. His latest book is Being Jewish and Doing Justice: Bringing Argument to Life (2011).