Mike Marqusee

This posting has these items:

1) Guardian: Mike Marqusee obituary, by Colin Robinson, January 2015;

2) Monthly Review: The perversities of the politics of identity., interview by Michael Letwin (JfJfP’s title), 2008;

3) Electronic Intifada: History lesson on the left’s Palestine blind spot by Asa WInstanley, July 2010;

4) The Guardian: Against the grain, Daphna Baram salutes Mike Marqusee’s honest appraisal of his radical journey through religion and politics, 2008;

5) The Independent: Next year – not in Jerusalem review of If I am not myself… by Mike Kustow (JfJfP signatory), 2008;

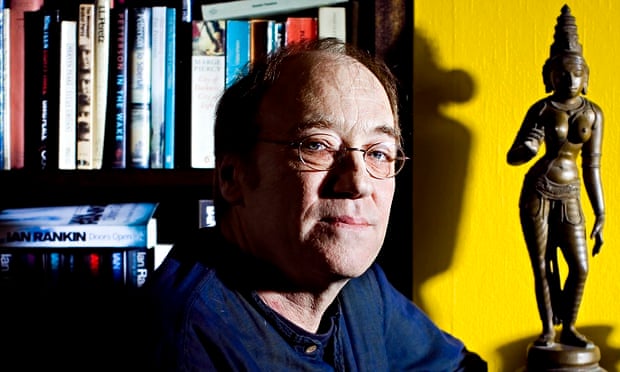

Photo of Mike in 2009 by Felix Clay

Mike Marqusee obituary

Journalist, political activist and author with eclectic tastes in sport, art and music

By Colin Robinson, The Guardian

January 15, 2015

The writer and political activist Mike Marqusee, who has died of cancer aged 61, enjoyed an intellect as dazzling as it was unique. A true polymath, he made the most of a boundless curiosity and a powerful memory to educate himself, and others, about a kaleidoscope of topics: Renaissance art, cricket and empire, British labour politics, Indian history and culture, Zionism, the music of Andalucía and Tamil Nadu, the poetry and art of William Blake, the American civil rights movement, the films of John Ford, the songs of Bob Dylan. The list could go on and on.

He sometimes speculated that such eclecticism resulted in his work being undervalued by specialists. If that was true, those in error failed to see how his range of interests often enabled one sphere of knowledge to provide an exhilaratingly original insight into another. Further, beneath the panoply lay a set of core values: a commitment to socialism, a belief in the transformative nature of art, a rigorous internationalism and a prioritising of intellectual and personal honesty heedless of cost. A joyful, hedonistic appreciation that life’s pleasures were there for the sampling was also a vital part of Mike.

He was born in New York, the son of John and Janet Marqusee, who were involved in property development, publishing and radical politics. Seeking to escape the pressures exerted on a precocious anti-war leader at his high school in Scarsdale, an conservative and affluent suburb of New York, Mike left the US for Britain in 1971. He read English literature at Sussex University before moving to north London, where he was to settle for the rest of his life.

Mike started out as a youth leader, based at Highbury Roundhouse, driving minibuses full of inner-city children on field trips around Britain. He later said that he learned more about politics from his work on the youth schemes there than in any of his subsequent activism.

Though a lifelong Marxist, Mike eschewed membership of the competing revolutionary tendencies that attracted many young radicals of the period. Indeed, in later years, he endured a bitter falling out with Socialist Workers party sectarians in the Stop the War Coalition, of which he was a founding member. He joined the Labour party around 1980, supporting the leadership of Haringey council in its fight against cuts and resisting Neil Kinnock’s attacks on the left that would pave the way for the emergence of New Labour, a development that saw Mike eventually leave the party. He chronicled Labour’s rightwing drift in a book co-authored with Richard Heffernan, Defeat from the Jaws of Victory (1992). He also became involved in the radical publication Labour Briefing, going on to become its editor. It was through his engagement with the Labour party that he met his partner, the housing rights barrister Liz Davies, who survives him. Together they formed an alliance that was as formidable in the political arena as it was supportive at home.

Mike had already written one book, his only published novel, Slow Turn (1988), which featured the game of cricket, a sport he had come to love while watching county matches in Sussex as a student. He turned his focus to the overlap between the game and nationalism, drawing openly on the legacy of CLR James to produce a rivetingly original analysis. Anyone But England (1994) went on to be shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award and laid the foundation for Mike’s regular cricket commentary in publications such as Wisden and The Hindu.

Two years later, he published another book on the game, War Minus the Shooting, that dealt with events surrounding the 1996 World Cricket Cup in South Asia. He co-founded Hit Racism for Six and could often be found practising his own swing in the nets at Finsbury Park, providing ample evidence that, in his case, the pen was mightier than the bat.

Mike now transferred his attention to another sport. Redemption Song (1999) was a paean to Muhammad Ali, setting the world heavyweight’s sporting achievements in the context of the political battles in the US. Moving seamlessly from descriptions of Ali’s bouts in the ring to the music of Sam Cooke, from the machinations of the Nation of Islam to the burgeoning of the anti-war movement, it was a fine example of Mike’s ability to weave together strands from different disciplines into a rich new cloth.

The distinction, so often snobbish, between high and popular culture held little appeal for Mike. He had a deep familiarity with Quattrocento art and I was lucky enough to be among a small group of friends that he introduced to the sublimity of Giovanni Bellini’s paintings on a trip to Venice. His mother was both a painter and a successful art dealer and Mike’s ability to scrutinise the formal qualities of a painting was probably acquired from her. But he was equally at home analysing the wider meanings of the plots of John Ford westerns or the character development in TV series such as Rome or The Wire. A large TV, a comfortable sofa and a strong joint was always a combination that made Mike happy.

His taste in music was equally catholic. Mike was a big fan of the driving rock of Springsteen and Steve Earle while, at the same time, his engagement with Indian culture resulted in several trips with Liz to the Carnatic music festival in Chennai. A subsequent enthusiasm for Cante jondo music saw expeditions to the flamenco bars of southern Spain and an immersion in the poetry of Lorca.

Mike wrote poems himself and published two collections, and it was the ear of a poet that he employed in his next book, Wicked Messenger (2003), an analysis of the lyrics of Bob Dylan. At the end of his life he was working on a book that examined the relationship between Thomas Paine and yet another poet, William Blake.

Mike’s penultimate book was perhaps his most daring and controversial. A firm atheist, he delighted in describing himself as a “deracinated Jew”. In If I Am Not For Myself (2008), he melded together, in characteristic fashion, his own family history, political theory and close reading of canonical religious texts, separating out Jewishness from its co-option by the state of Israel.

In 2007 Mike was diagnosed with the bone marrow cancer multiple myeloma. Though it took him a couple of years, he predictably reverted to type, responding to his illness by writing about it. His last book, The Price of Experience, a collection of pieces about his disease (several of them for this paper), ranges over withering contempt for the mercenary activity of the big drug companies, an appreciation of the fastidious care provided to him by the NHS and its selfless staff and quiet sensitivity concerning how we talk to each other about illness.

In his introduction to the book, which, like a number of his titles, I had the privilege of publishing, he wrote: “Writing itself was a precious continuity with ‘life before cancer’. While so many of my other capacities had been taken away from me, I could still write.” Now he no longer can. However, through his books and journalism, we will still be able to remember his voice, with its glorious combination of profusion and singularity.

• Michael John Marqusee, writer, born 27 January 1953; died 13 January 2015

The perversities of the politics of identity.

Interview by Michael Letwin

Monthly Review, 2008

Your book is subtitled “Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew.” Were you always an Anti-Zionist?

No. I grew up, in the 1960s, in a left-wing household in a largely Jewish New York suburb — where Israel was seen as a progressive beacon and support for the Jewish state was taken for granted. My parents combined activism in the civil rights and anti-war movement with blind devotion to the Israeli cause. I attended a Reform Sunday school in which Israel played a much more important role than God or the Hebrew Bible. When Israel won the Six Day war, I felt the same triumphant glow as everyone else in my community.

What changed your mind?

The contradictions I came to feel between my anti-racist and anti-war views and what Israel was doing. It was a prolonged process, pushed along by two factors. First, events in the Middle East and the increasingly obvious injustice of Israeli policy towards the Palestinians. Second, the stubborn and repeated re-emergence of Palestinian struggle, without which, we wouldn’t be talking about the issue at all.

Why did you choose to make your grandfather the focus of the book?

After my mother died in 2001, I inherited a box stuffed with my grandfather’s papers: diaries, letters, campaign literature and hundreds of columns written for a Bronx newspaper called the Jewish Review, from the ’30s to the early ’50s. He spent several decades as a political activist — pro-labour, pro-civil liberties, anti-racist and anti-fascist. He got involved in the Scottsboro campaign and chaired the Bronx branch of the Committee to Aid Republican Spain. He joined in the street confrontations against the anti-Semitic Christian Front and fiercely criticized the passivity of the Jewish establishment. Though he worked with Communists, and loathed red-bating, he was never a member of the party and had no patience with what he considered to be party-line regimentation. In 1946 he ran for Congress on the American Labor Party ticket and secured 20% of the vote.

Fascism and antisemitism turned him into a militant Jew (he was actually half Irish), but he only became interested in Zionism from about 1940 — when he interviewed Jabotinsky (and criticized him for making a war-time alliance with the British).

In 1948, he filled the pages of the Jewish Review with his glee at Israeli independence (“the Bar Mitzvah of our people”) and his outrage at the British and the Arabs. He had always seen himself as an anti-imperialist, he hated the British Empire and saw the Arabs as savage pawns of the British. All his worst traits come to the fore. His tone is militaristic and chauvinist and at times bloodthirsty. The man who had been a stand-up champion of refugee rights since he’d opposed the Quotas Act of 1924 was now, in 1948, almost gloating over the Palestinian exodus. One of the questions my book sets out to answer is how that transition came about. Partly, it’s an object lesson in the perversities of the politics of identity.

But my grandfather wasn’t alone. The Western Left overwhelmingly supported the Jewish state. In the presidential campaign of 48, Henry Wallace constantly attacked Truman’s alleged betrayal of the Jews in Palestine, which he, and much of the Left, viewed as part of Truman’s Cold War, anti-Soviet, pro-British policy turn.

In my grandfather’s papers, I found echoes of current controversies and of my own experiences as a political activist. For me it was an intriguing example of life on the Left, in a particular time and place, and how activists, like everyone else, are driven both by inner demons and larger forces.

Some on the Left limit their criticism of Israel to the occupation of additional Palestinian territory since 1967. Is that the extent of the problem?

No. The Palestinian refugee population — descendants of those driven out in 1948 — now numbers at least 5 million, one half of whom live in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. One million remain stateless, with no form of identification other than a UNWRA cards. The end of the occupation would strengthen them in various ways, but in itself would not rectify their situation or meet their demands for justice. In addition there are 1.4 million non-Jews in Israel, who suffer institutionalised discrimination and segregation and are confined to second-class citizenship.

These two groups of people — the refugees and Palestinians within Israel — are not just additional problems that can be addressed separately. They are part of the wider and deeper problem created by the Zionist state. At this point in history, it’s clear that the Zionist mission has an in-built exclusivist and expansionist dynamic. Maintaining a Jewish state requires maintaining a sizeable majority Jewish population with an ideological commitment to the state. Palestinian demands — and actually existing Palestinians — stand in the way of that. Zionism is an obstacle not only to the realisation of a single democratic state in Palestine but immediately to any acceptance of genuine self-determination in any form for the Palestinians.

Why do Palestinians refuse to “recognize the Jewish state,” and insist on the right of return for refugees from the Nakba in 1948?

The Palestinians’ right of return is guaranteed in Resolution 194 which has been reaffirmed by the UN many times since 1948. It embodies a basic and widely recognised principle, without which, there would be no protection for victims of wars, and ethnic cleansing would be legitimised. To abandon the right of return is to abandon several million people, and to exempt Israel from the requirements we make of other states. It’s not an impossible utopian demand, either. It’s something that could be practically implemented through negotiations, though it would of course require major concessions from the Israeli side.

While Israel refuses to recognise its responsibility for the refugees and their descendants, it demands that these very people recognise its own “right to exist”. It’s an extraordinary demand. No one denies the fact of Israel’s existence, but why should anyone anywhere be compelled to recognise the “right to exist” of a particular state formation? What’s being demanded here is an ideological seal of approval: support for the right of the Jewish state to exist, in perpetuity, in Palestine, regardless of what that entails for others. Palestinians and their supporters are condemned because they refuse to certify as legitimate a national project built on dispossession and ethnic supremacy.

Is there reason to hope that a greater number of Jews will reject Zionism?

Yes. Israel’s record has now been so exposed that it requires huge amounts of wilful blindness to continue to defend it. The facts are now too well documented, too available. Also, despite everything, there remains a leftward bent within the US and British Jewish populations. It’s a tradition that’s been profoundly eroded over the years but is still quite tangible, and it can’t be reconciled with Israel’s behavior or Zionism’s assumptions.

Despite strenuous efforts to keep Jews in the corral, most Jews in the US or Britain live wider lives and their views are shaped by the same things that shape other people’s views. Like others, they find ethno-nationalism and blind chauvinism unappealing. I think the aggressive tactics of the ADL and the like have to some extent backfired — though in the meantime they’ve taken plenty of victims. As the pro-Israel establishment finds doubt spreading among the people it claims to represent, it gets more strident and vicious. One of the themes of my book is that Zionism’s hegemony within Jewish communities was the product of a particular history; it wasn’t automatic; it’s changed over time and it’s changing now.

How do you evaluate the significance of growing opposition to a “two-state solution” and increasing support for one democratic state in all of historical Palestine?

It springs from Israel’s refusal to countenance any meaningful form of Palestinian independence. All the “two state solutions” envisioned by Israeli leaders are aimed at perpetuating Jewish supremacy.

In one sense, the argument is simple: democrats oppose ethnically-privileged states everywhere. The logic behind the demand that Israel becomes “a state for all its citizens” ought to be self-evident, yet when it was raised by Palestinian members of the Knesset, it was met with outrage and those who raised it were subject to repression.

Is it conceivable that a Zionist state in the Middle East will rest at peace with its neighbours? It would certainly continue to require huge subsidies from the USA and other Western countries and would continue to tie the Jewish population of Palestine to the broader imperial project in the region. That’s a recipe for endless instability and injustice.

History lesson on the left’s Palestine blind spot

Book review

If I am not for myself: Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew

by Mike Marqusee

256pp, Verso, 2008 hb £11.89, 2010 pb, £5.99

By Asa Winstanley, Electronic Intifada

July 30, 2010

Mike Marqusee’s book If I am Not For Myself, newly available in paperback, is a fascinating, meandering sort of family memoir. From the subtitle “Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew” one expects an autobiography. As it turns out, it mostly tells the story of Marqusee’s grandfather Edward V. Morand, based on an inherited suitcase full of his old personal letters, newspaper clippings and so forth.

Morand (or EVM as he is referred to throughout) was an American lawyer, sometimes columnist and Jewish activist. The fight against antisemitism on the streets of New York during the long build-up to the Second World War forms a large part of the narrative thrust of the book. Marqusee takes us through the Jewish and leftist milieus of the period, with extensive detours via extracts from his own life story, with analysis on religion, history and politics.

We meet Jewish prophets, heretics, thinkers, militants and activists: from Amos to Spinoza, the Haskalah and the Bund. They are a mixed bag, but their stories are rarely less than intriguing. Marqusee recalls a politically formative moment from his childhood, when an Israeli soldier, fresh from the 1967 occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, visits his Jewish weekend school. The exotic visitor’s dismissive attitude towards the Palestinians makes a deep impression on the 14-year-old Mike:

“… they were better off now, under Israeli rule. ‘You have to understand, these are ignorant people. They go to toilet in the street.’ Now something akin to this I had heard before. I had heard it from the white Southerners I had been taught to look down upon … So I raised my hand … It seemed to me that what our visitor had said was, well, racist” (p. 59).

Around the dinner table, Marqusee senior angrily dismisses his son’s reaction as “Jewish self-hatred.”

In the 1930s, EVM was a loud proponent of a campaign to boycott Nazi Germany. As obvious as that sounds in hindsight, it was a controversial move in those days before war had started. Zionist groups such as the American Jewish Committee and the Board of Deputies of British Jews were actively against the boycott. Perhaps this is not so surprising when we consider the attitude of the World Zionist Organization (WZO), which Marqusee describes as “by far the most active opponent of the boycott.” He recounts the 1933 deal between the WZO and Nazi Germany known as “Haavara” — the “transfer” of German Jews and their money to Palestine (p. 96).

“German Jews were permitted to remove some of their funds in the form of German-produced capital goods which were then sold in Palestine (as well as in the US and Britain),” Marquesee recounts. A part of this investment would then be recouped later. Referencing Lenni Brenner’s 1983 book Zionism in the Age of Dictators, Marqusee says the Nazi-Zionist scheme “accounted for some 60 percent of all capital invested in Palestine between August 1933 and September 1939” and was vital in sustaining the Zionist settlement movement through both the depression and the Arab Revolt (p. 96).

The main curiosity of Marquee’s focus on his grandfather is that EVM was an ardent Zionist. He was a supporter of the Irgun terrorist militia, even while it was carrying out some of its worst atrocities against the Palestinians. The Lehi, aka Stern Gang militia’s terrorist methods he described as “unorthodox and unprecedented exploits” (p. 172).

Why would a book ostensibly about an anti-Zionist Jew turn out to focus on a Zionist? In many ways, EVM fits the typical “progressive except for Palestine” mould of the pro-Israel liberal one still finds today. Although he was never a communist (“Don’t join the Communist Party and don’t get pregnant,” he loudly warned his cringing daughter when dropping her off at university (p. 210)) he took the side of persecuted communists during the red scares of the pre-war period. He took part in the founding of the American Labor Party (ALP) and spoke out against racism in many forms. He almost got into a bar fight in defense of anarchist martyrs Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti the night they went to the electric chair. He was prophetic when it came to the dangers of Hitler and fascism (although his First World War experiences and antipathy towards the British Empire left him initially wary of US involvement in the war).

And yet when it came to Palestine, the documents show a “close-up view of a man of conscience making a colossal historical error,” as Marqusee describes it (p. 180). Despite his anti-racist positions in other areas, EVM wrote about Palestinians and other Arabs in almost exclusively racist and orientalist terms: “hostile bandit chiefs,” “Arab hordes,” “marauders,” “robbers,” etc. (pp. 185-186)

Marqusee ultimately concludes with a reclamation: “EVM, forgive me, but I think my anti-Zionist politics are actually an evolution of your legacy, working its way through another half-century of history” (p. 295). This seems to me an unrealistic and rose-tinted — if understandable — view of Morand’s legacy. Yet Marqusee’s focus on his grandfather is vindicated by the insight it gives us into the liberal-leftist blind spot that Palestine was, and still is for some.

The Palestinians and the Arabs in general simply did not figure into the calculations of the contemporary left — and the few times they did, they were only understood as the “Arab bandits” of the imagined Orient. Marqusee points out that the Palestinian revolution or Arab Revolt of 1936-39 and its brutal suppression by the British occupation forces was ignored by the Western left: “In contrast to the Spanish Civil War, or even Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, the most intense and sustained anti-colonial insurgency of its time was ignored by the left in Europe and North America and actually denounced by the British Labour Party as ‘fascist.’” Marqusee points out that Herbert Morrison, Labor Party leader in the 1930s, put it this way: “The Jews have proved to be first class colonizers, to have the real good old Empire qualities” (p. 127).

Marqusee describes this as the left’s “failure to imagine the people on the receiving end of your dreams. It’s a failure rooted in Western and white supremacy … EVM’s writings of 1948 abound with it, and offer inadvertent testimony to the racist character of the Nakba and Nakba denial” (p. 210).

Personally, I would have been willing to trade some of the detail of Morand’s life in favor of more focus on such almost-forgotten figures of Jewish anti-Zionism as Rabbi Elmer Berger of the American Council for Judaism, as well as the more well-known groups such as the Bund. Nevertheless, If I am Not For Myself remains a fascinating critical insight into Zionism, and amounts to a crucial warning from history on Palestine for the liberal left of today.

Asa Winstanley is a freelance journalist based in London who has lived in and reported from occupied Ramallah. His website is www.winstanleys.org.

Daphna Baram salutes Mike Marqusee’s honest appraisal of his radical journey through religion and politics, If I Am Not for Myself

Guardian, April 19, 2008

The Mishnaic scholar Old Hillel is known, in both the Jewish and non-Jewish world, for his saying “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” It is no accident, however, that Mike Marqusee, a New York-born Jew who has been living in the UK for the past two decades, picked one of Hillel’s more enigmatic and possibly least understood ethical aphorisms to mark the route of his journey to anti-Zionism: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am for myself alone, what am I? If not now, when?”

It takes a complex ethical motto to lead one through the complex relationships between almost each and every Jew in the world during the past century, the Zionist movement, and the state of Israel. While Zionists claimed Hillel’s saying as one of their slogans, implying that the Jewish people should act for themselves by joining a national movement, creating their own state and redeeming themselves from living “among the nations”, Marqusee’s take on this old piece of Jewish wisdom led him to the opposite conclusion: “In defining myself as an anti-Zionist Jew, I am for myself, and at the same time and without contradiction for others.”

Marqusee’s book consists of three threads, woven into one journey of consciousness. The first is an account of the life and times of his grandfather, Ed, son of a Jewish mother and an Irish father, hence a “proper” Jew by any religious standard, who still felt the need to change his last name from the Irish Moran, into the somewhat more Jewish-sounding Morand. Ed V Morand, or EVM as his grandson got used to calling him, was a lawyer and a journalist with political aspirations. He was anti-imperialist, anti-racist, an ardent liberal, a supporter of workers’ rights, civil rights, and human rights, a champion of Black liberation in America, an anti-fascist – and an ardent Zionist. His grandson struggled to understand how a man who dedicated his life to fighting against every wrong in the world could have been so adamant in his denial of the wrongs done to the Palestinian people, the atrocities committed by the Zionists during the 1948 war – known as the nakba to Palestinians, and as “the war of independence” to Israelis.

Equally, he could not understand how his father, a peace campaigner, a member of the Civil Rights Movement in the US in the 1960s, and a radical activist against both the Korean and Vietnam wars, did not encourage him when he decided that the enlightened ideas he was brought up on should be applied equally to Israel’s behaviour in the territories it conquered in 1967.

When the teenage Marqusee comes home from school one day in 1969 and says that an Israeli soldier who was invited to speak to his class was a racist, and that in his own opinion “If the US was wrong in Vietnam … then Israel was wrong in taking all that Arab land”, a fight breaks out around the dinner table. In the heat of the argument his father throws at him the worst insult of them all. He calls his son “a self-hating Jew”. This is possibly the peak moment of the second thread of the book, which consists of Marqusee’s own personal journey from the all-Jewish-American-liberal home in which he was born and bred to his current rejection of Zionism. As one who has been through a similar journey, I always find accounts of such personal-political transitions fascinating – so I regretted that he chose to be so economical with this particular aspect of his own personal history.

But anything the second thread lacks is compensated for by the third, which is a tour-de-force of political and cultural analysis of various aspects of Jewish, Zionist and anti-Zionist history and politics. Marqusee touches on many painful spots – from the nakba, the catastrophe which led to the expulsion of most Palestinians from their land, through to the treatment of Middle Eastern Jews by Israel and the Zionist movement, and the form of antisemitism which is, ironically, inherent in Zionism’s rejection of “Diasporic Judaism”. The comparisons he draws between Zionism, Hindu nationalism, and other similar and dissimilar political phenomena are incisive and accurate. He shies away from no controversy, and his account of recent dealings with incidents in and around the anti-war movement – which attracted accusations of antisemitism – are penetrating and intellectually honest.

It sometimes seems that Marqusee’s task is too big for one book; EVM seems to deserve a whole biography for himself, Mike Marqusee’s own road to anti-Zionism is worthy of further expansion, and the analytical part of the book could have easily have given rise to a separate publication. And yet If I Am Not for Myself is a good read, and for many it will make sense of a few questions which, with the growing domination of Zionism over the Jewish discourse, seem to be more and more bewildering: can one be a Jew and not a Zionist? Can one be a lefty and a Zionist? And how exactly do all those confusing definitions cross each other’s paths?

It is enjoyable also because of the vivid way in which Marqusee brings back to life his passionate, life-loving, grumpy and flamboyant grandfather, who roamed the Bronx at the time when “the slogan Free Palestine meant support for a Jewish State and A Palestinian – a Jewish settler; Where the Zionist anthem ‘Ha-Tikva’ took its place with ‘The Internationale'”. And even if the grandson rejected a major ingredient of his grandfather’s politics, he certainly inherited his bold spirit, and his insistence on always calling a spade a spade. In this, If I Am Not for Myself is a manifesto for a whole generation of Jewish radical activists who refuse to be deterred by the threat of being labelled, and libelled, as self-haters. Those who brand them so, says Marqusee in his conclusion, “want to steal our selves from us – appropriate our selves to their cause – and speaking as a self, I’m damned if I’m going to let them get away with it.” His book is a vital contribution to making sure that indeed they will not.

By Michael Kustow, The Independent

March 21, 2008

When I had finished this book, I wanted to cheer. It concludes with “Confessions of a ‘Self-Hating Jew'”, a passionate dismissal of the accusation that anyone who criticises Israel must be an anti-Semite and, if Jewish, a self-hater. The chapter is all the more powerful since it is triggered by autobiography: a rebuke from the author’s father to his son’s anti-Zionism. The personal and the political coalesce, making this book, subtitled “the journey of an anti-Zionist Jew”, a rare and precious work. Its polemical force is anchored in experience.

Mike Marqusee has previously written fine studies of complex, fruitfully divided selves (Bob Dylan, Muhammad Ali) and some of the most resonant sports writing since CLR James. Coming to political activity in the 1960s, he has battled through the sectarian disputes of the Left. He casts a distinctive gaze on the world in his column in The Hindu. He’s an American who has lived half his life in London, who joined the Labour Party and came out again, who worships William Blake, backed Rock Against Racism, and feels inalienably Jewish – but not Israel-right-or-wrong Jewish.

Reading this book while Israel pounded Gaza, and Palestinian rockets slammed into Sderot, has been like a glimpse of clarity in a climate of chaos. I wanted a copy in the hands of every politician and general, every zealot in the Middle East. If Jewish adolescents got Marqusee’s book as a barmitzvah present, there might be a chance of avoiding the repetition of history’s mistakes.

Marqusee compares and contrasts his way of being a Jew and a socialist with the life of his cantankerous grandfather, Ed Morand. Armed with a battered leather briefcase of his grandfather’s papers, he conjures up this garrulous and eloquent ancestor from the Bronx.

Grandfather Ed kept his convictions unstained by the political distortions of his lifetime. But with the creation of Israel in 1948, Ed embraced a militant Zionism that, in Marqusee’s view, betrayed and simplified Jewish inheritance. There is sad, wrenching drama in the way the author parts company with his precursor. From Ed, Marqusee learned to hammer thoughts out to their ultimate expression, which makes him an exhilarating, if occasionally pugnacious, writer. His own hard-fought journey teaches Marqusee to avoid submitting himself to Zionism, submerging what the poet Nathaniel Tarn called “the beautiful contradictions” into its rhetoric.

When I started this book, I thought its subtitle over the top. But Marqusee convinces me of its appropriateness. His anti-Zionism is grounded in a detailed historical account, and his conclusion is the credo of a man who has followed the dreams and seen through the delusions of the ideological battlefield. “I cannot subcontract my ethics, my relationship with the human race, to a state or a religion – or indeed a political party. For me, being an anti-Zionist is inextricable from being a democrat, a socialist, a humanist and a rationalist.” Within anti-Zionism is “a necessary affirmation: of internationalism, of humanity”, and of “one’s own humanity”.

Marqusee is aware of the dangers of analogy. Is it really any more than name-calling to say that the Israelis are behaving like Nazis? Do Palestinians really seek to re-run the Nazi crusade by “driving Israelis into the sea”? Marqusee can turn a trenchant phrase against such robotic assertions: “The presumption [of the self-appointed gate-keepers] that they can adjudicate on our Jewishness or lack thereof is as fatuous as the anti-Semites’ presumption that our Jewishness determines our character.”

His title comes from the “marvellously succinct ethical-existential catechism” of Rabbi Hillel: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” It’s often quoted by backs-to-the-wall spokesmen to mean that Israel must be stronger than its neighbours, because the world is against it, and its only defence is deterrent attack. Marqusee is determined not to be co-opted by simplifications of the complex fate of being Jewish. He wants Jews and Israelis not only to reflect on their special experience but to enter the perspectives, hopes and tragedies of others. Hillel, he reminds us, went on to ask, “If I am only for myself, what am I?”

Michael Kustow’s biography of Peter Brook is published by Bloomsbury