Yom Kippur war led to crushing military burden and role

Destroyed Israeli M60 tank, Yom Kippur war, 1973.

40 years on, the IDF finally emerges from the bunker

The 1973 war shaped the way in which Israel’s military and intelligence saw strategic developments in the region. Now, with a new generation at the helm and new challenges in the Arab world, the IDF is beginning to adapt to the changes in and around it.

By Amos Harel, Ha’aretz

September 13, 2013

For nearly four decades, the Yom Kippur War has cast its enormous shadow over the Israeli defense establishment. The trauma of 1973 shaped the way in which the establishment’s leaders, Israel Defense Forces commanders and intelligence chiefs perceived the developments in the country’s strategic reality, the way in which they treated intelligence information, and the precautions they took to prevent another military surprise. The images of the Israeli POWs on Mount Hermon, the desperate cries of the soldiers under attack at the Suez Canal strongholds, the angst-ridden consultations in the General Staff’s underground headquarters − all of these not only left an ineradicable impression on the war’s veterans, but also ended up being passed down to subsequent generations like a kind of Oral Law.

The war’s influence was evident everywhere. It reinforced several basic elements shared by its veterans and those who came after them, which went unchallenged for many years: an inherent skepticism regarding what intelligence agencies really know about the enemy’s intentions; the need to preserve broad margins of safety regarding the possibility of a surprise war erupting; and a basic lack of faith in the judgment of political leaders (which grew still more pronounced after the duplicitous war in Lebanon in 1982). To this day, the soldiers at outposts on the Hermon and Golan Heights are still trained to cope with a surprise offensive of “Syrians on the fences,” even though four decades have gone by.

Only in the past two years has the IDF begun to free itself slightly from the shadow and to adjust some of these longstanding conceptions to the new era. In part, this is a natural consequence of generations changing. Among the top defense brass, only Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon and commander of the General Staff Corps, Maj. Gen. Gershon Hacohen, saw active duty in the war. Benny Gantz is the first IDF chief of staff since 1973 who has not been a veteran of that war; a month before it broke out, he had entered the ninth grade. The other generals on the General Staff today were in elementary school at the time. The current commander of the Paratroopers Brigade, Col. Eliezer Toledano, was born the week that Yom Kippur’s paratroopers were fighting at the Chinese Farm. His colleague Golani Brigade commander Col. Yaniv Asor was a year old when the brigade re-conquered the Hermon.

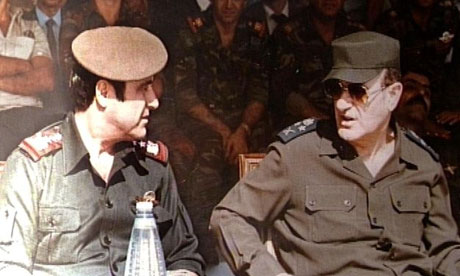

In power in 1973, L-R: Rifaat and his brother President Hafez al-Assad who seized power in Syria in a military coup in 1970; President Anwar Sadat, appointed President Egypt 1970; Golda Meir, elected by Mapai as party leader to become Prime Minister of Israel, 1969.

But the conclusions from the Yom Kippur War, some still relevant today, are also being reexamined in view of the shakeup that took hold of the Arab world nearly three years ago. The deep processes still underway there, whose consequences are not yet clear, obligate Israel to take a new look at the region and at the potential military threats that it faces. The change in the nature of challenges will also gradually dictate a change in Israel’s response and in the IDF’s structure.

The intelligence failure is generally noted as the main reason for the Yom Kippur fiasco. The low probability the Military Intelligence Directorate ascribed on the eve of the war to the possibility of a coordinated Egyptian-Syrian offensive remains a source of eternal disgrace. But in its wake, together with the requisite need for relying on parallel evaluative bodies − and the insistence on allowing junior officers to express an independent opinion, even when it counters official assessments − there are also negative norms that became entrenched. These include a clear-cut tendency on the part of the evaluators to cover their asses, with the object of expressing all possible scenarios and thus preventing the possibility of future accusations of complacency and arrogance.

Only lately have there been growing signs that MI is kicking this nasty habit. This could be seen clearly two weeks ago when, in view of the American statements about an imminent attack in Syria, MI was not afraid to offer the assessment that only a low probability existed that Damascus would retaliate with military action against Israel. Presumably, the attacks this year against Syrian weapons convoys and depots, which have been ascribed abroad to the Israel Air Force, were accompanied by similar intelligence assessments.

The most dramatic change the Arab Spring has generated from Israel’s standpoint concerns the depletion in the power of the conventional military threat posed by Arab states. The first days of the 1973 war revealed a numerical inferiority of the [Israeli] ground forces in the Golan Heights and Suez Canal and a difficulty in gaining air superiority in the face of the threat of anti-aircraft missiles. That was the tragic background that yielded the massive growth in the IDF’s ground and air forces in the years after the war. The army created more and more armored divisions, determined that, as the saying goes, “Masada shall not fall again.”

Thus was born what economists describe as the lost decade after the war, in which tremendous defense-related expenses paralyzed the economy. Likewise, in subsequent decades, the IDF concentrated on preparing for a major confrontation, mainly with the Syrian army. Even though in practice it dealt day-to-day with what was then termed “low-intensity wars” − such as guerrilla and terror confrontations with Hezbollah and the Palestinian organizations − a major military contest was seen as the primary scenario for which to prepare.

Even after Syria acknowledged its inferiority in the conventional realm, and focused its military’s procurement and training on those areas where it felt it had an advantage (steep-trajectory missiles and rockets, air-defense systems, fortifications and anti-aircraft missiles), the IDF continued to behave as though a war between armored divisions might break out at any moment.

Squirming in their seats

However, the enormous erosion in the Syrian military’s ability since the civil war broke out there has led, belatedly, to a change in mindset on the Israeli side. This summer, in view of budget cuts, Chief of Staff Gantz drew up a plan for structural changes in the IDF that includes slashing the number of armored and artillery units and eliminating air force squadrons. The General Staff is convinced that the abilities developed in recent years − accurate intelligence, firepower from air and ground, and mainly the possibility of coordinating these components − will compensate for the damage the cutbacks will cause.

But it was riveting to see some of the veteran military commentators, so-called graduates of the Yom Kippur War, squirm in their seats as Gantz described his plan to them. Full support for it has come from Ya’alon, who declared that the military must change because future conflagrations will no longer look like the war of ‘73. Ya’alon, who fought during the war in Sinai as a reservist paratrooper and returned for an officers course thereafter, has spoken out frequently in recent weeks about the lessons he learned, among other occasions, at a conference for IDF top brass about the war, held at the Palmahim base this week.

There he said:

“One of the seeds of that war’s failure was the great sense of victory of the Six-Day War, which led to excessive self-confidence, arrogance, complacency, carelessness. Senior officers had a culture then of ‘I am, and there is no other beside me.’ Immediately after I was appointed head of the MI Directorate in 1998, I set about reading the report of the Agranat Commission, and went to meet its protagonists, too. From them, I learned the extent of the tragedy: MI’s leaders in those years were clearly excellent people. They were overcome, and not only they, by arrogance and immodesty. There was no room for another opinion, another view, different thinking.”

Each of us, Ya’alon told the senior officers of today, “should maintain modesty and beware of the euphoria that follows successes. The challenge for all of us these days is to be alert to change, the pace of which is tremendous. The correct way is to encourage within the organization a culture that seems

contrary to hierarchical military logic, in which the commander is the one who determines and knows. We need an organizational culture that encourages all ranks to be critical, to cast doubt, to reexamine basic assumptions, to get outside the framework and eventually act in keeping with operational discipline.”

Ya’alon did not mention the issue of internal oversight. In the past decade, largely in response to the shock of the Second Lebanon War, a deeply troubling tendency has been exacerbated in the IDF, whereby senior officers toed the line and were afraid to criticize their commanders, after having concluded that such audacity would end up delaying their promotion. The first who dared point this out openly was Brig. Gen. Amir Abulafia, now the commander of a reservist division, who in an article in the military magazine Maarachot in 2010 criticized officers’ fear of expressing an independent opinion.

Abulafia warned that the phenomenon imperils the IDF’s ability to fulfill its purpose: protecting the country. Gantz, who is aware of the danger, is making a fierce effort to rescue the army from intellectual conservativeness. Ya’alon, who supports this, contends that, “in the IDF they are once more not afraid to think.”

The Yom Kippur War highlighted other sensitive seam-lines, such as the mutual relations between the military command and the political leadership, the public and the media. Historians who have published studies of the war in recent years, among them Prof. Uri Bar Joseph and Dr. Yigal Kipnis, emphasized the refusal of Golda Meir’s government to entertain diplomatic initiatives in the three years leading up to the war. The findings, some of them new, have intensified the feeling that the roots of the war’s surprise lay also in a serious political fiasco − and these have led to numerous comparisons to the suspicious and sour attitude of Benjamin Netanyahu’s government vis-a-vis peace efforts today.

On the other hand, criticism of politicians can come from another angle entirely: Today is also the anniversary of the Oslo Accords of 1993. To a large degree, the formative military experience of the generals on the current General Staff goes back to the years of combat against Palestinian terrorism, culminating in the second intifada, but which generally accelerated in the wake of Oslo. Moreover, on the eve of the shakeup in the Arab world, Netanyahu blocked recommendations − which had the vociferous support of the IDF − to move toward forging a peace treaty with the Assad regime that would have entailed giving back to Syria the entire Golan Heights. Where would Israel be today without that strategic asset?

It is hard, therefore, to draw definitive historical conclusions and make them fit a uniform ideological mold, when reality continues to change. But generally speaking, the approach to the peace process of the present General Staff, although not directly expressed in public, remains moderate and relatively sober-minded. Israel’s generals are very far from the prevalent image of warmongers.

One of the main speakers at the conference in Palmahim this week was Prof. Yagil Levy, who focused on the war’s effect on Israeli society (the fact that an invitation was extended to Levy, who frequently attacks the IDF’s conduct in the territories, attests to a new spirit in the Gantz era). Levy diagnoses in the Yom Kippur War the roots of long-term processes, primarily the mounting military burden on society, in terms of money and manpower and a concomitant increase in society’s expectations from the IDF, as if to show that the increased burden is justified.

Today, Levy sees a tendency in the army to focus on professionalization, with the IDF seeking to compensate for a decline in people’s willingness to sacrifice their sons in battle by means of improved technology, and to explain that trend by means of the market economy − an observation that met with discomfort among part of the audience at the conference.

In this relationship there is a third vertex to the triangle: media outlets. The military commentator for the website Ynet, Ron Ben-Yishai, this week wrote about his experiences as Israeli television’s military correspondent during the ‘73 war and also gave links to footage of stories from previous years.

The IDF’s confidence, the smugness despite the worrisome signs on the Egyptian side − these are clearly evident in the run-up to the war. The military correspondent himself says in passing, toward the end of an item from 1971, that the IDF will rely less on reservists “next time,” because behind the enlisted forces in the strongholds will be the immense strategic expanse of Sinai.

Two years later, the immensity of that mistake became clear. Alongside the intelligence and diplomatic failings, Yom Kippur highlighted the total collapse of the arrogant perception that the flimsy order of battle of enlisted units on the borders would be enough to stop a Syrian and Egyptian offensive, should one even occur. The scorn for the Arabs’ ability, following the victory in 1967, is apparently at the heart of the failure in 1973. Therein resides one of the main lessons of the war, which is relevant in 2013 as well, even if all the rest of the circumstances have changed: the need to take the potential rival with all seriousness and prepare accordingly.