Gaza's underground economy

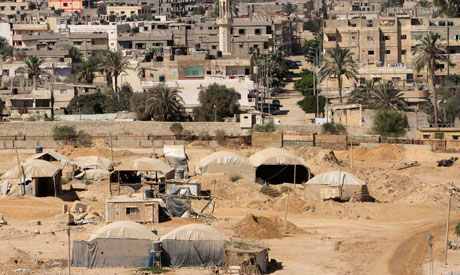

Entrepreneurs/smugglers drive a coach and horses – or several thousand cars a year – through Israel’s embargo. Photo by Marius Arnesen/Flickr

Only one of these items is recent (2). The rest are reports, analyses, overviews. What is striking is how many of them predict change in a ridiculous and unsustainable situation – and how little has changed.

1) Nat. Geographic: The Tunnels of Gaza , An American journey of discovery, December 2012;

2) Reuters: Egypt Steps Up Gaza Tunnel Crackdown, Dismaying Palestinians, latest closures, June 24, 2013 ;

3) Irin: Analysis: A tunnel-free future for Gaza? , August 2012, from a report from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs;

4) ICG: Light at the end of their tunnels? , August 2012;

5) FT: Gaza looks beyond tunnel economy, 2010;

The tunnels of Gaza are a lifeline of the underground economy but also a death trap. For many Palestinians, they have come to symbolize ingenuity and the dream of mobility.

By James Verini, National Geographic

December 2012

For as long as they worked in the smuggling tunnels beneath the Gaza Strip, Samir and his brother Yussef suspected they might one day die in them. When Yussef did die, on a cold night in 2011, his end came much as they’d imagined it might, under a crushing hail of earth.

It was about 9 p.m., and the brothers were on a night shift doing maintenance on the tunnel, which, like many of its kind—and there are hundreds stretching between Gaza and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula—was lethally shoddy in its construction. Nearly a hundred feet below Rafah, Gaza’s southernmost city, Samir was working close to the entrance, while Yussef and two co-workers, Kareem and Khamis, were near the middle of the tunnel. They were trying to wedge a piece of plywood into the wall to shore it up when it began collapsing. Kareem pulled Khamis out of the way, as Yussef leaped in the other direction. For a moment the surge of soil and rocks stopped, and seeing that his friends were safe, Yussef yelled out to them, “Alhamdulillah!—Thank Allah!”

Then the tunnel gave way again, and Yussef disappeared.

Samir heard the crashing sounds over the radio system. He took off into the tunnel, running at first and then, as the opening got narrower and lower, crawling. He had to fight not to faint as the air became clouded with dust. It was nearly pitch black when he finally found Kareem and Khamis digging furiously with their hands. So Samir started digging. The tunnel began collapsing again. A concrete-block pillar slashed Kareem’s arm. “We didn’t know what to do. We felt helpless,” Samir told me.

After three hours of digging, they uncovered a blue tracksuit pant leg. “We tried to keep Samir from seeing Yussef, but he refused to turn away,” Khamis told me. Screaming and crying, Samir frantically tore the rocks off his brother. “I was moving but unconscious,” he said. Yussef’s chest was swollen, his head fractured and bruised. Blood streamed from his nose and mouth. They dragged him to the entrance shaft on the Gazan side, strapped his limp body into a harness, and workers at the surface pulled him up. There wasn’t room for Samir in the car that sped his brother to Rafah’s only hospital, so he raced behind on a bicycle. “I knew my brother was dead,” he said.

I was sitting with Samir, 26, in what passed for Yussef’s funeral parlor, an unfinished-concrete room on the ground floor of the apartment block in the Jabalia refugee camp where the brothers grew up. Outside, in a trash-strewn alley, was a canvas tent that shaded the many mourners who had come to pay their respects over the previous three days. The setting was a typical Gazan tableau: concrete-block walls pocked by gunfire and shrapnel from Israeli incursions and the bloodletting of local factions, children digging in the dirt with kitchen spoons, hand-cranked generators thrumming—yet another Gaza power outage—their diesel exhaust filling the air.

“I was so scared,” Samir said, referring to the day in 2008 when he joined Yussef to work in the tunnels. “I didn’t want to, but I had no choice.” Thin, dressed in sweatpants, a brown sweater, dark socks, and open-toe sandals, Samir was nervous and fidgety. Like the others in the room, he was chain-smoking. “You can die at any moment,” he said. Some of the tunnels Yussef and Samir worked in were properly maintained— well built, ventilated—but many more were not. Tunnel collapses are frequent, as are explosions, air strikes, and fires. “We call it tariq al shahada ao tariq al mawt,” Samir said—“a way to paradise or a way to death.”

Everybody, it seemed, had injuries or health problems. Yussef had developed a chronic respiratory illness. Khamis’s leg had been broken in a collapse. Their co-worker Suhail pulled up his shirt to show me an inches-long scar along his spine, a permanent reminder of the low ceilings. “In Rafah,” Samir said, “it felt like a bad omen was present all the time. We always expected something bad to happen.”

In the Gaza Strip today hero status is no longer reserved for the likes of Yasser Arafat and Ahmed Yassin—the late leaders, respectively, of Fatah and the Islamic Resistance Movement, better known as Hamas—or for Palestinians who’ve died in the fighting that has rocked this wisp of land since its creation 63 years ago. Now tunnel victims like Yussef—28 when he died—are also honored.

“Everybody loved him,” Samir said. He was “so kindhearted.” On the walls of the makeshift funeral parlor hung posters with Koranic verses of sympathy sent by the family that ran the grade school where Yussef had studied, by the imam of his mosque, and by the local functionaries of Gaza’s bitter political rivals: Fatah, the former ruling party, and Hamas, the militant group that now governs the strip. The most prominent poster was from the local mukhtar, a traditional Arab leader. It showed Yussef in a photograph taken five months earlier, on his wedding day. He was wearing a white dress shirt and a pink tie. He had short-cropped hair and eager, gentle eyes. The poster read, “The sons of the mukhtar share condolences with the family in the martyrdom of the hero Yussef.”

The entrances to smuggling tunnels are clearly seen on the border between Egypt and Rafah August 8, 2012 – until Egypt has its next crackdown. Photo by Reuters.

The Rafah underground isn’t new—there have been smuggling tunnels here since 1982, when the city was split following the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, which left part of it in Gaza and part in Egypt. Back then the tunnel well shafts were dug in home basements. The Israeli military, knowing that the tunnels were used for arms trafficking, began demolishing homes that harbored tunnels, as did some Palestinians who wanted to keep the tunnel economy under their control. When that didn’t end the smuggling, Israel later expanded the demolitions, creating a buffer zone between the border and the city. According to Human Rights Watch, some 1,700 homes were destroyed from 2000 to 2004.

Gaza’s tunnels became imprinted on the Israeli public consciousness in 2006, when a group of Hamas-affiliated militants emerged in Israel near a border crossing and abducted Cpl. Gilad Shalit. Shalit became the embodiment of a ceaseless war, his face staring out from roadside billboards much like the faces on martyrdom posters that adorn the walls in Jabalia and the other camps. (He was finally released in a prisoner exchange in the fall of 2011.)

After Hamas won elections in 2006, it and Fatah fought a vicious civil war—which Hamas won the next year, taking control of the Gaza Strip—and Israel introduced an incrementally tightening economic blockade. It closed ports of entry and banned the importation of nearly everything that would have allowed Gazans to live above a subsistence level. Egypt cooperated.

Anything that can be sold in Gaza is brought through the tunnels. Photo by Richard Mosse, Time

Since Hosni Mubarak’s departure in early 2011, Egyptian officials have expressed remorse for cooperating with Israel. Egypt has reopened the small Rafah border crossing, though it still prevents some Gazans from coming through. Its new president, Mohamed Morsi, who wants to keep Hamas at a distance, has not pledged to help Gaza in a way that many Gazans had hoped he would. In August, after a group of 16 Egyptian soldiers were killed by gunmen in northern Sinai, Egypt temporarily shut down the Rafah crossing and demolished at least 35 tunnels.

After Israel introduced the blockade, smuggling became Gaza’s alternative. Through the tunnels under Rafah came everything from building materials and food to medicine and clothing, from fuel and computers to livestock and cars. Hamas smuggled in weapons. New tunnels were dug by the day—by the hour, it seemed—and new fortunes minted. Families sold their possessions to buy in. Some 15,000 people worked in and around the tunnels at their peak, and they provided ancillary work for tens of thousands more, from engineers and truck drivers to shopkeepers. Today Gaza’s underground economy accounts for two-thirds of consumer goods, and the tunnels are so common that Rafah features them in official brochures.

“We did not choose to use the tunnels,” a government engineer told me. “But it was too hard for us to stand still during the siege and expect war and poverty.” For many Gazans, the tunnels, lethal though they can be, symbolize better things: their native ingenuity, the memory and dream of mobility, and perhaps most significant for a population defined by dispossession, a sense of control over the land. The irony that control must be won by going beneath the land is not lost on Gazans.

The region of Gaza has been fought over—and burrowed under—since long before Israel assumed control of it from Egypt in 1967. In 1457 B.C. Pharaoh Thutmose III overran Gaza while quashing a Canaanite rebellion. He then held a banquet, which he enjoyed so much that he ordered chiseled into the Temple of Amun at Karnak: “Gaza was a flourishing and enchanting city.” Thutmose was followed by Hebrews, Philistines, Persians, Alexander the Great (whose siege of Gaza City required digging beneath its walls), Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Tatars, Mamluks, and Ottomans. Then came Napoleon, the British, Egyptians again, and Israelis, though to this day there is disagreement about whether Gaza would have been considered part of the land the Bible says God promised the Jews. This is partly why expansionist-minded Israelis have focused more intensely on the West Bank than on Gaza; the last Israeli settlement in Gaza was vacated in 2005.

But Gaza is the heart of Palestinian resistance. It’s been the launching area for a campaign, now in its third decade, of kidnappings, suicide bombings, and rocket and mortar assaults on Israel by Gazan militants—much of this sanctioned, if not expressly carried out, by Hamas.

The tunnels supply the government with all the materials used in public works projects, and Hamas taxes everything that comes through them, shutting down operators who don’t pay up. Tunnel revenue is estimated to provide Hamas with as much as $750 million a year. Hamas has also smuggled in cash from exiled leaders and patrons in Syria, Iran, and Qatar that helps keep it afloat.

Samir told me that Hamas leaders and local officials are in business with tunnel operators, protecting them from prosecution when workers like his brother die needlessly. He’s convinced that corruption and bribery are rampant. His friends agreed. “Damn the municipality!” Suhail blurted out as Samir spoke.

In 2010, after Israeli naval commandos attacked a Turkish flotilla off the Gaza coast, to international outrage, Israel said it had relaxed the blockade. But today there is still only one ill-equipped access point for goods, whereas the West Bank has many more. Israel makes it extremely difficult and expensive for the UN’s Relief and Works Agency and other aid agencies—the source of life and livelihood for thousands of the 1.6 million Gazans—to import basic materials for rebuilding projects, such as machinery, fuel, cement, and rebar.

According to a Gazan customs official I spoke with, the spring of 2011 saw imports at their lowest level since the blockade began. And what did get through, he said, was often degraded: used clothing and appliances, junk food, castoff produce. It was impossible “to meet basic needs,” the official said, insisting that the hesar, or siege, as Gazans call it, was crippling them. Even some of Israel’s oldest supporters agreed. British Prime Minister David Cameron lamented that under the blockade, Gaza had come to resemble a “prison camp.”

Photographer Paolo Pellegrin and I made many trips to Rafah’s tunnels. The drive from Gaza City, an hour to the north, afforded a dolorous tour. The aftermath of the civil war and of Israel’s most recent invasion of the strip—Operation Cast Lead in 2008–09—was evident everywhere. Stepping out of our hotel each morning, often after a night torn open by Israeli air strikes on reported militant hideouts, we took in the absurd sight of a five-story elevator shaft standing alone against the skyline, the hotel that had once surrounded it reduced to rubble. The Palestinian Authority’s former security headquarters cowered nearby, a yawning missile hole in its side. Bullet-chewed facades and minarets marked the horizon.

Driving south, we passed Arafat’s bombed-out former compound, littered with rusted vehicles, then proceeded along the coastline, once one of the prettiest on the eastern Mediterranean but now home to the skeletons of seaside cafés and to fetid tide pools. Heading inland, we passed abandoned Israeli settlements, their fields sanded over, their greenhouses lying in tatters. South of Rafah the ruins of the Gaza Airport languished as if in a Claude Lorrain landscape—used only by herders grazing their sheep and Bedouin their camels. Our interpreter, Ayman, told us that after the airport was built, he was so proud of it that he took his family there on weekends for picnics. “Look at the destruction,” he said, shaking his head. “Everything. Everything is … destructed.” “Destructed” is a favorite malapropism of Ayman’s. It’s apt. “Destroyed” doesn’t quite capture the quality of ruination in Gaza. “Destructed,” with its ring of inordinate purpose, does.

As we arrived in Rafah, life teemed again. A byword for conflict, Gaza is also synonymous in Middle Eastern memory with that other staple of human history, commerce. Armies marching into the desert depended on its gushing wells and fortress walls, but to merchants through the millennia, Gaza was a maritime spur of the spice routes and agricultural trade. Travelers sought out its cheap tobacco and brothels, and even today Israeli chefs covet its strawberries and quail. From the 1960s to the late 1980s, Gaza and Israel enjoyed a symbiotic commercial relationship not unlike that of Mexico and the U.S. Gazan craftsmen and laborers crossed the border every morning to work in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, while Israelis shopped in the tax-free bazaars of Gaza City, Khan Younis, and especially Rafah, which some old Gazans still call Souk al Bahrain: “the market of the two seas.” The first intifada, which lasted from 1987 to 1993, put an end to much of that.

Passing a jammed intersection overlooked by a Hamas billboard showing a masked militant wielding a bazooka, we entered the Rafah market. The din and fumes of generators commingled with the shouts of vendors, the braying of donkeys, and the sweet smoke of shawarma spits. Block after block of shops and stands sold consumer items, much of which had come through the tunnels.

It’s no secret that Gaza’s tunnel operators are brazen, the more so since the Arab Spring began. Just how brazen was not apparent until we emerged from the market, and an expanse of white tarpaulin tent roofs opened up before us. It stretched along the border wall in both directions, tent after tent as far as the eye could see. Beneath each was a tunnel. They were all in the so-called Philadelphi route, the patrol zone created by the Israeli military as part of the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty. All were in full view of Egyptian surveillance towers and sniper nests.

Unable to hide my astonishment, I exclaimed to no one in particular, “This must be the biggest smuggling operation on Earth.”

Every few hundred yards bored-looking cops barely out of adolescence sat outside tents and shacks, AK-47s on their knees. Hamas forbids journalists here, so we drove to the farthest end of the corridor and parked behind a dirt hill. Furtively, we walked into the first tent we saw. There we met Mahmoud, a man in his 50s who used to work on a farm in Israel. He lost his job when the border was closed during the second intifada, so he and a group of partners pooled their savings. In 2006 they started digging, and a year later they had a tunnel.

After nervous negotiations with Ayman, Mahmoud agreed to show me how it worked. “Come here,” he said, leading me to the well shaft. Suspended over it was a crossbar with a pulley, from which hung the harness for lifting and lowering goods and workers. The harness was attached to a spool of metal cable on a winch that could lower a worker the 60 or so feet down the shaft to the tunnel opening. Mahmoud’s tunnel was about 400 yards long, but some can extend half a mile. On this day boxes of clothing, mobile phones, sugar, and detergent were coming in; the day before it had been four tons of wheat. Mahmoud earned anywhere from several hundred to a few thousand dollars a shipment, depending on what he brought in. Like many tunnel operators, he made enough to keep his tunnel open and support his family but not much more.

Five to 12 men work in 12-hour shifts, day and night, six days a week, and Mahmoud communicated with them via a two-way radio that had receivers throughout the tunnel. The men earned around $50 a shift but sometimes went weeks or months between payments. On the dirt floor beneath the tarpaulin were dusty cushions where they could rest after a shift. There was also a charred black kettle on the remnants of a wood fire, a strand of prayer beads, and stacks of halved plastic jerricans, the ad hoc sleds that are used to move goods along the tunnel floor.

Goods are dragged through the tunnels on hand-pulled ‘sleds’. Photo by Richard Mosse, Time

“Would you like to go down?” Mahmoud asked. Before I could say no, I said yes. Moments later his men were enthusiastically strapping me into the harness and lowering me into the cool, dank well. I tried to imagine what it would be like if this were my daily routine, going to work by descending six stories into the earth at the end of a cable. At the bottom it was chaotic: dim lightbulbs flickering, radio traffic blaring, dust-covered workers hauling sacks out of the sleds. The mouth of the tunnel was large enough to accommodate several stooping men, but it soon became so narrow that I had to crouch, my shoulders scraping the walls.

When I got back to the surface, a group of police suddenly appeared. They had seen our car. “You shouldn’t be here,” their leader said. Ayman apologized, and soon the officer was regaling me with his account of uncovering a load of cocaine and hashish at a tunnel the day before. Smuggling drugs is lucrative but very risky. They arrested the operator, the officer said, and the well was filled in. He then ordered Paolo and me to go, saying we’d have to get permission from the central government in Gaza City if we intended to come back. “Don’t go into the tunnels,” another cop warned. “You’ll die.”

In the tunnels death comes from every direction. One operator told of the time he tried to smuggle in a lion for a Gaza zoo. The animal was improperly sedated, awoke in the tunnel mid-trip, and tore one of the workers apart. Another operator showed me a video on his mobile phone of three skinny young men lying dead on gurneys. They were his cousins, he said, and had worked in his tunnel. I asked why they had no contusions or broken limbs. “They were gassed,” was the reply. According to some Palestinians, when Egypt has been pressed by Israel to cut down on smuggling, its troops have occasionally poisoned the air in tunnels by pumping in gas. Egypt has denied this.

After days of wrangling with assorted offices, we returned to the tunnel corridor. Word had spread that an American reporter was snooping around, and even with our official escort, many operators shunned us. But some warmed up.

The most welcoming was Abu Jamil, a white-haired grandfather and the unofficial mukhtar of the Philadelphi corridor. Abu Jamil is credited with having opened the first full-time tunnel. It quickly attracted too much business to be serviced by a well, so he dug an enormous trench for loading and unloading goods. Abu Jamil had opened several more tunnels, and his sons, grandsons, nephews, and cousins worked for him. He claimed to no longer care about the profit. “For me it’s a way to challenge our circumstances,” he said, as a dump truck backed into the trench to pick up a load of Egyptian sandstone. Asked what else he’s brought in over the years, he smiled wearily. “Oh, everything.” By which he meant cows, cleaning supplies, soda, medicine, a cobra for the zoo.

At a tunnel nearby we saw a shipment of potato chips arrive; at another, mango juice; at another, coils of rebar; at another, the familiar blue canisters of cooking gas. We reached one tunnel as 300 dripping Styrofoam boxes filled with fish packed in ice were being unloaded. Taxis and cars sent by restaurants and wives had pulled up to take delivery. The partners who ran this tunnel were young, in their 30s. They specialized in lambs and calves, they said, but fish was cheaper, and since Gazan fishermen were kept within a tight nautical limit by the Israeli Navy, seafood was always in demand.

Just then a man entered the tent and whispered to one of the partners. He didn’t want sardines—he wanted to be smuggled into Egypt. This is common. Some Gazans go by tunnel to the Egyptian side of Rafah for medical treatment. Some use the tunnels to escape, others to have a good time for a night. I heard that there were even VIP tunnels for wealthy travelers, with air-conditioning and cell phone reception.

As the two men haggled, there was yelling outside the tent. I rushed out to find a tunnel worker about to punch Paolo. The man was screaming that he didn’t want his picture taken. Every time a journalist comes here, he shouted, a tunnel is bombed. How, he yelled, could he tell that we weren’t spies? I’d noticed that when Ayman tried to persuade tunnel operators to speak with me, the word “Mossad” was often uttered. They presumed that if Paolo and I weren’t with the CIA, we must be with the Israeli spy agency. The tunnel worker’s paranoia is understandable, given that Israel’s surveillance of Gaza is constant, as the ceaseless buzz of drones overhead attested. And in recent memory, Israeli commandos have entered the tunnel zone. A few, as the Israeli press has documented, died in bomb explosions—booby traps set by Palestinians.

Although unemployment is endemic—the rate in Gaza is more than 30 percent—the Gaza Strip is full of would-be entrepreneurs. On the shore north of Gaza City, next to bombed-out cafés, fish farms are being built. On the roofs of buildings pockmarked by machine-gun fire, hydroponic vegetable gardens are being planted, and in Rafah, just west of the tunnels, a sewage-processing plant is now running, its pond lined with concrete pylons taken from the border wall.

Yet for the majority of Gazans, the tunnels remain the lifeline. One day in Rafah I met a man who was digging a well with the help of his two sons, using a horse in place of a winch. I asked if he worried about his sons’ safety. He said yes, of course. But he had no other job prospects and couldn’t afford to keep his sons in school. Fixing me with a skeptical look that suggested all the distance in the world between us, he said curtly, “Insa.” One of Arabic’s beautifully expressive idioms, the word means essentially, “That’s life.”

Alongside the tunnel economy is another, born of destruction. The UN estimates that Operation Cast Lead created more than half a million tons of rubble, which has become a currency in its own right. It’s everywhere, and the rubble collectors are usually teams of children wielding mallets and hammers, breaking down the stuff, sifting it, loading it onto donkey carts, and bringing it to one of the many concrete-block factories that have sprung up. This is how Gazans, unable to legally import construction materials, are rebuilding. A government economist told me that rubble alone accounted for a 6 percent drop in unemployment in 2010.

Gazans are still hopeful that the Arab Spring might bring a change in their circumstances, though so far it has not. There is talk of opening the border with Egypt, but when that might happen, or indeed whether it will at all, is unclear.

The economy of destruction takes on permutations that might have pleased Thutmose III: One night Paolo and I attended a wedding celebration in a bomb crater. It also takes ugly turns: According to an interview in an International Crisis Group report, “a handful of rockets are launched by young militants hired by local merchants whose profits would decline if Israel’s closure were further relaxed.” This is hideous enough to be believable, but the militants I met were entrepreneurially minded in a more peaceful way. One afternoon I interviewed an Islamic Jihad fighter at a patrol ground near Bayt Hanun. Wearing head-to-toe camouflage and a headband advertising his willingness to die for Allah, an AK-47 in his hands, and a 9-mm pistol strapped to his chest, he admitted that most days he studies business administration at the university. “Jihad is not a job,” he said.

Back in Jabalia, I talked with Samir about his future. “There is no chance I can go back to the tunnels,” he said. I asked what he’d do instead, and he waved his hand to indicate the room we were sitting in. As it turned out, his brother Yussef had signed a contract to rent this space. When Yussef wasn’t working in the tunnels, Samir explained, he was learning to become a beekeeper. He’d planned to open a honey shop here. Samir wanted to take it over in Yussef’s stead. And when I last heard from Samir, in September, the shop was up and running. When Yussef died, his wife was three months pregnant with their first child. She miscarried shortly afterward. She is now married to Yussef’s youngest brother, Khaled, who manages the honey shop with Samir. They keep a picture of Yussef on the wall.

Egypt Steps Up Gaza Tunnel Crackdown, Dismaying Palestinians

By Reuters/Amwal Al Ghad

June 24, 2013

Egypt has intensified a crackdown on smuggling tunnels between its volatile Sinai desert and the Gaza Strip, causing a steep hike in petrol and cement prices in the Palestinian territory.

Palestinians involved in the tunnel business say that the campaign, which began in March and has included flooding of underground passages, was ramped up in the past two weeks before a wave of opposition-led protests in Egypt expected to start on June 30.

Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi has come under political fire at home over a strong challenge to his authority by militant Islamists in the Sinai who have attacked Egyptian security forces in the peninsula.

Egypt’s military, struggling to fill a security vacuum in the Sinai since autocrat Hosni Mubarak was swept from power in 2011, has pledged to shut all tunnels under the Gaza border, saying they are used by militants on both sides to smuggle activists and weapons.

The moves against the tunnels have dashed the hopes of many Palestinians that Mursi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood from which Hamas was born, would significantly ease Egyptian border restrictions on Gaza, which is also subjected to blockade by Israel.

“Business is clinically dead,” said Abu Bassam, who employs 40 workers in a Palestinian tunnel network in Rafah, a town on the border. “Tunnels are almost shut down completely.”

Only 50 to 70 tunnels, out of hundreds that have provided a commercial lifeline for the Gaza Strip, are still open and in partial operation, owners said. Other tunnels are used to smuggle in weapons for militants from Hamas and other groups.

The Egyptian army has sternly warned residents in Sinai not to approach the fence with Gaza and to stop trading through tunnels or face punishment, according to Palestinian tunnel owners who learned about the order from Egyptian counterparts.

“Today we have to pay extra money to convince an Egyptian driver to bring goods to us…, resulting in rising prices of basic materials here,” said Abu Ali, another tunnel owner, standing beside the shaft of his deserted tunnel.

HIGH PRICES

The price of cement in Gaza has soared from 350 shekels ($95) a ton to 800 shekels ($217). Palestinians who bought relatively cheap petrol smuggled from Egypt now have to pay for fuel imported from Israel selling for double the price.

The scene of long queues of vehicles outside petrol stations has become common in past two weeks, with taxi drivers waiting to snap up small quantities of fuel trickling in from tunnels that are still operating.

One tunnel owner, who employs 24 workers, said he was now bringing in 50 tons of food products a day compared with 300 tons two weeks ago.

Many Gaza residents complain they have been without cooking gas for weeks, with tunnel supplies low and imports from Israel scarce.

Ghazi Hamad, deputy foreign minister in the Hamas government, said it understood Morsi’s complicated internal situation and would be prepared to close all tunnels if Egypt allowed goods through Rafah, its only Gaza crossing.

At Rafah, where cross-border passenger movement increased significantly soon after Morsi took office, passage has been particularly slow recently and hundreds of people have had to delay their trips.

Egyptian officials cited technical problems.

Israel maintains an overland and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip but has eased some import restrictions in the past several years in the face of international criticism.

It announced on Monday the closure of its only commercial crossing with Gaza until further notice in response to overnight cross-border rocket attacks by Palestinian militants.

Analysis: A tunnel-free future for Gaza?

By IRIN

August 23, 2012

GAZA CITY– This month’s border attack in the Sinai Peninsula, which killed 16 Egyptian soldiers, has bolstered calls to shut down a network of underground tunnels between Egypt and the isolated Gaza Strip. The tunnels have been used for years to smuggle goods into Gaza and, Egypt alleges, fighters into the Sinai.

But Hamas, which rules the Gaza Strip, sees this as an opportunity.

Publicly and in discussions with Egyptian officials, Hamas has been pushing to use the Rafah border crossing between Egypt and Gaza for commercial trade. Ghazi Hamad, deputy minister of foreign affairs, has said a free trade zone might soon “liberate Gaza”.

“Once the Rafah crossing operates as a hub for goods, the tunnels will become history,” Azzam Shawwa, a former Minister of Energy in the Palestinian Authority (PA), told IRIN.

The tunnels are the main commercial trade routes in and out of the Gaza Strip, part of the occupied Palestinian territories.

Israel has kept its borders with Gaza closed except for the Kerem Shalom crossing, where the passage of goods is heavily restricted. The Agreed Principles for Rafah Crossing, signed by the Palestinian Authority and Israel in 2005, included plans for formal trade, but the deal was frozen when Hamas came to power in the Gaza Strip in 2006.

Gaza-Egypt relations have also been strained over the blockade of Gaza, though they have improved since former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak was ousted from power last year. The recent attacks – and their humanitarian impact – have made the calls for change all the more urgent.

“In the end, what happened in Sinai might turn out to have a positive impact on the future relations between Egypt and Gaza,” Mustafa Sawaf, former chief-editor of the Hamas-affiliated Filistin newspaper, told IRIN.

Since 5 August, when Egypt closed the crossing and started shutting down some of the tunnels, the import of fuel and construction material has reportedly declined by 30 and 70 percent, respectively, and power cuts have reached up to 16 hours a day, according to the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

A free trade zone would provide Gaza with more facilities, energy and access to goods, Hamad, who is also the chairman of the border crossings authority in the Gaza Strip, told IRIN, “but it wouldn’t turn Gaza into some kind of Taiwan. We have to remain realistic. It should bring people back to a normal life”.

Prospects for free-trade zone

With a free-trade zone, Gaza could potentially import and export goods and raw materials through the Egyptian seaport of Al-Arish without paying custom duties to Egyptian authorities.

Another option would be an industrial free zone allowing Palestinians from Gaza to pass freely into industrial areas in Egypt for work, said Shawwa.

Asked whether a free-trade zone would be in Israel’s interest, Ilana Stein, deputy spokesperson of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told IRIN, “We have to wait until there are serious suggestions by the parties, Palestinians and Egyptians. Once something clear is there, we are ready to discuss it.”

But analysts said that the Rafah crossing is not designed for any of these possibilities and would have to be upgraded. In addition, Egypt, struggling to provide its 90 million people with the fruits of its recent revolution, is unlikely to want Palestinian workers vying for scarce jobs amid rising poverty.

Tunnel profiteers

There is likely to be internal opposition too. While Fatah, the political party ruling the West Bank, has supported Egypt’s move to shut down the tunnels, saying they “serve a small category of stakeholder and private interests”, analysts say there could be significant resistance to attempts to permanently shut them down.

Some US$500-700 million in goods are estimated to pass through the tunnels every year, charged by the Hamas government with duties of at least 14.5 percent since early 2012, according to a new report by the International Crisis Group (ICG).

Several influential families in control of the tunnels profit from every item that passes through them. It costs $25 to smuggle a person through and around $500 for a car; in 2011, 13,000 cars are believed to have come into Gaza through the tunnels.

“Eight hundred millionaires and 1,600 near-millionaires control the tunnels at the expense of both Egyptian and Palestinian national interests,” Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas was quoted as saying in The Economist.

There is a class of people benefitting from the tunnels… But Hamas can solve that by involving them in legitimate trade.The tunnels have recently contributed to a construction boom, with apartments, parks and mosques being built with help from investors like the Saudi-led Islamic Development Bank. The transition to a tunnel-free future will have to address these interests.

“It is true that there is a class of people benefitting from the tunnels,” Nathan Thrall, senior analyst at ICG, told IRIN. “But Hamas can solve that by involving them in legitimate trade.”

Hamas would also earn more money in customs than it does in the current situation, where middlemen profit too. “I don’t think that this is as large an obstacle as others,” Thrall said.

Complex politics

One of the other main obstacles is how Israel will react.

Calls for improved trade relations with Egypt have sparked fears that Israel would use the opportunity to rid itself of all responsibility for Gaza: Once Rafah is opened to commercial goods, Israel could argue it no longer has to keep open the Kerem Shalom crossing – the only official entry point for imported goods. “That would be the end of Israeli responsibility for Gaza,” said Thrall.

Such a move could undermine efforts to reach Palestinian unity by further disconnecting Gaza from the West Bank. For this reason, even Hamas is careful not to push too hard for imports into Gaza.

“We don’t want to see Israel closing Kerem Shalom,” Hamad said. “Israel just wants to push us towards Egypt. But we do consider Gaza as part of the Palestinian homeland.”

“It’s a serious discussion,” added Shawwa, the former PA minister. “Do we want an independent economy of Gaza? That might take us into a new era of Palestinian separation.”

Kerem Shalom is the only crossing point where commercial and humanitarian goods are allowed to enter Gaza from Israel, and even when open, aid agencies have struggled to consistently import enough supplies to meet operational needs.

Some analysts speculate the newly elected president in Egypt, Islamist Mohamed Morsi, will make a trade zone conditional on the success of Palestinian reconciliation, while others say that he could also move forward in the absence of Palestinian unity.

“The relationship between Egypt, Israel and Hamas is complex,” said Abdel Monem Said, director of the Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo. “Morsi knows he can’t really allow Palestinians in Gaza to starve. And there is pressure from inside the [Muslim] Brotherhood to support Hamas.” On the other hand, Egypt is constrained by close security cooperation with Israel in Sinai, he told IRIN.

“By allowing people to pass, Morsi would do enough to meet his humanitarian obligations,” said a European diplomat in Jerusalem who requested anonymity. “The security issue with Israel is more pressing at the moment.”

Mkheimar Abu Saada, a political scientist at Gaza’s Al-Azhar University, says Egypt is in a very delicate situation: “On one hand, they don’t want to be seen as cooperating with Israel by imposing a siege on the Gaza Strip like Mubarak did. In the meantime, they don’t want to be blamed for terminating the relationship with Israel.”

As such, Hamas acknowledges its hopes for a free trade zone are unlikely to be realized in the near future.

For now, it is focused on “more realistic options”, like allowing more people to cross Rafah and exporting from Gaza – with some success. After Egypt gradually eased restrictions at Rafah in May, Morsi agreed with Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh last month on increasing the number of crossing travelers to 1,500 per day and increasing the amount Qatari fuel allowed to pass.

“I do think there are some chances that Rafah will be used for commercial purposes and not only exports,” Hamad said, “but maybe it is still too early for Egyptians to give an answer right now.”

Light at the end of their tunnels?

Hamas and the Arab Uprisings

International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N°129

August 14,2012

BRIEF EXTRACT

Providing security and stability to Sinai. The situation in Sinai has become a top concern for the Israeli government, which sees it as a no-man’s-land to which various militant groups – and advanced weaponry – find their way.289 Egypt also has an interest in stabilising Sinai, where turmoil is fuelled by an illicit economy created in part to

circumvent the limited access to the Strip.

The 5 August attack that killed sixteen Egyptian soldiers – after which the militants stormed the Israeli border in a stolen truck and armoured vehicle – brought into stark relief the urgency of working to reduce militancy and criminality alongside Gaza. Egypt responded with a military campaign that included the first helicopter airstrikes in Sinai since Israel withdrew from the peninsula in 1982, together with destruction of a number of Sinai-Gaza tunnels, closure of the Rafah crossing and restrictions on Palestinian travel to Egypt. Though the attackers’ identity remains unclear, Israeli and Egyptian officials noted that public opinion in Egypt turned against Hamas and Gaza in the wake of the incident. Hamas officials say they are optimistic their relations with Egypt will not be harmed but they understand Egypt under Morsi likely will have less tolerance for instability on Gaza’s southern border. 292

Hamas could thus see benefit in a stable Sinai that prevents the strengthening of Islamist challengers, bolsters

Morsi and facilitates legal passage of goods and other commodities, such as fuel, between Egypt and the Strip. 293

Footnotes

289 U.S. and Egyptian officials have also said that Sinai is a large concern. Crisis Group interviews, Cairo, Tel Aviv, Washington, March-July 2012. An Israeli defence official said, “Sinai is a no-man’s land. The Bedouin are in control. After the attack in August [2011], we permitted six [Egyptian] battalions to enter Sinai. Not all six came. And they have done some small things, but basically they have had no effect. In the past couple of months, there have been some moves by the Egyptian military to reassert control. They told me they arrested twenty Bedouin recently. And they found some arms caches. But what they have arrested and what they have confiscated, it is a drop in the

sea. Hamas knows they have more freedom of manoeuvre now than they did under [former Egyptian intelligence chief] Suleiman and Mubarak. Tunnels are operating without restrictions, weapons are flowing in, Hamas can operate in Sinai. They know they can’t launch attacks from Gaza, because of the retaliation from Israel, so they can try to operate in Sinai instead”. Crisis Group interview, Tel Aviv, 8 March 2012.

292 A Hamas official went so far as to say that he believed relations between Gaza and Egypt would be improved in the wake of the attack. Three days before Morsi sacked Egypt’s top two generals, the Hamas official said, “the attack will benefit both Hamas and Morsi. It benefits Morsi by giving him an opportunity to get rid of some of the generals of the old regime [in the wake of the attack, Morsi fired the governor of North Sinai and replaced the head of Egyptian intelligence with Mohamed Raafat Shehata, a broker of the Shalit deal whom Hamas officials say they respect]. And it allows Morsi to take action in Sinai, showing he is a doer. The attack benefits Hamas by helping accelerate Egypt’s realisation that they need to shut down the tunnels and open up a free trade zone at Rafah”. Crisis Group interview, Gaza City, 9 August 2012.

293 Indeed, one week after the Sinai attack, a Hamas spokesman in Gaza, Salah Bardawil, said, “Hamas is ready to close the tunnels in return for opening the Rafah crossing permanently for persons and goods. My movement is not only ready to approve the closure of the tunnels but also to help close them”. Sama News, 12 August 2012. Two days before Bardawil’s statement, an Egyptian diplomat expressed scepticism that Hamas would ever close the tunnels completely: “If Hamas says they will close all the tunnels in exchange for opening Rafah to goods, do you think anyone in the Egyptian government will believe them for one second? Do you really think that if we open Rafah to goods the tunnels will disappear? Of course they will keep the tunnels open, at least for smuggling weapons and Tramadol [a popular, illicitly-trafficked painkiller]”. Crisis Group interview, 10 August 2012.

Gaza looks beyond tunnel economy

By Tobias Buck, Financial Times

May 23, 2010

RAFAH–The young tunnel worker flashes a broad smile as he tightens his grip, and starts lowering himself down a narrow shaft into the sandy depths below Rafah.

Seated on a piece of wood attached to an electrical winch, he descends 18 metres and starts crawling into the narrow tunnel that continues for another 700 metres, linking this border town in the southern Gaza Strip with Egypt. Somewhere below, his colleagues are shoring up the tunnel’s precarious supports, damaged by a recent explosion.

While the dangerous work proceeds below, Nasim, one of the owners of the tunnel, waits in the tent that covers the entrance. He is among a small number of Gazans who have made a fortune by undermining, quite literally, Israel’s economic embargo of the strip. Until recently, tunnel owners could expect to make at least $50,000 (€40,000, £35,000) in net profits every month by smuggling fuel, cigarettes and other goods from Egypt.

For close to three years, the tunnels below Rafah have offered a unique lifeline to Gazans, who are otherwise deprived of all but the most basic humanitarian supplies. They have also allowed Hamas, the Islamist group that controls the strip, to replenish its coffers and rebuild its military arsenal, making the tunnels a target for Israel.

Today, however, Nasim is more worried about the decline in business than he is about Israeli air raids. He says that Hamas – whose security officers can be seen in the tunnel area – is taking an ever greater cut of the operators’ profits. Moreover, the prices of many smuggled goods have fallen in recent months, thanks to a supply glut that is on striking display across the strip.

Some argue that Gaza’s tunnel economy is becoming a victim of its own success. Hundreds of tunnels have shut down over the past year as a result of greater Egyptian efforts to stop the flow of goods – and weapons – into the strip. But the remaining tunnels, about 200 to 300 according to most estimates, have become so efficient that shops all over Gaza are bursting with goods.

A smuggler carries fast food to be delivered through an underground tunnel linking the Gaza Strip to Egypt, on 13 May 2013 in Rafah. Photo by AFP

Branded products such as Coca-Cola, Nescafé, Snickers and Heinz ketchup – long absent as a result of the Israeli blockade – are both cheap and widely available. However, the tunnel operators have also flooded Gaza with Korean refrigerators, German food mixers and Chinese air conditioning units. Tunnel operators and traders alike complain of a saturated market – and falling prices.

“Everything I demand, I can get,” says Abu Amar al-Kahlout, who sells household goods out of a warehouse big enough to accommodate a passenger jet.

However, Mr al-Kahlout regards his suppliers in Rafah with distaste. “The tunnel business is not real business. They [the tunnel operators] are not respectable: if they were able to cut off your skin and sell it, they would do so,” he says.

His criticism is echoed by other business leaders in Gaza, who insist that the smugglers are creating a false sense of economic improvement while damaging the territory’s battered private sector.

Generators supply electricity to the tunnels. Photo by Richard Mosse, Time

They concede that the tunnels are providing essential goods, yet the smugglers are also bringing in precisely the simple consumer items that could be manufactured in Gaza, especially if sanctions were eased.

“We are just replacing legitimate businessmen with illegitimate businessmen” says Amr Hammad, a Gaza-based entrepreneur and deputy head of the Palestinian Federation of Industries. Flush with cash, the tunnel operators will soon “govern the whole economy of the Gaza Strip”, Mr Hammad predicts.

For most Gazans, the period since the end of Israel’s three-week offensive in January last year has brought little improvement. According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, the number of “abject poor”, who depend on food aid, trebled to 300,000 – or one in five of all Gazans – in 2009.

One western official says the tunnels act like a “humanitarian safety valve”, but cautions that they offer no solution to economic decline. As Mr Hammad says: “An economy cannot just depend on tunnels.”