Israel only country ever to refuse UN's universal human rights check

In this posting, 1)Israel only country to snub UPR, Daily Telegraph; 2) statement from 15 NGOs; 3) & 4) Adalah’s submission to UPR and questions it should ask; 5) definition of UPR.

Israel’s expansion in the West Bank is subject to discussion at every council session. Photo by AP. Caption and photo chosen by Daily Telegraph to illustrate this article.

Israel refuses to appear before UN human rights review

Israel has become the first country to refuse a request to appear before the United Nations Human Rights Council for review.

By Phoebe Greenwood, Tel Aviv, Daily Telegraph

January 29, 2013

As Israeli representatives were due to stand before the council in Geneva answering its concerns over Israel’s human rights record on Tuesday, foreign ministry officials were instead issued media statements confirming the unprecedented boycott of the council’s Universal Periodic Review.

“Israel is the only country in the world not allowed to not even be a candidate for a seat in [the UNHRC], a body that allowed Gaddafi’s Libya to preside over it and counts Zimbabwe, Pakistan and Cuba among its members. Is this fair?” justified Yigal Palmor, spokesman for Israel’s foreign minister.

The Jewish state cut all ties with the UNHRC in March, complaining that the council’s decision to approve a fact-finding mission into Israel’s settlement activity in the West Bank revealed an “inherent bias”.

Every one of the UN’s 193 member states is obliged to participate in the Universal Periodic Review. Israel last participated in 2008. However, the human rights watchdog has censured Israel more often than any other member. The introduction of Agenda Item 7 has ensured that Israel’s expansion in the West Bank is subject to discussion at every council session.

Eviatar Manor, Israel’s ambassador to the UN, placed a phone call to the UNHRC on January 10th requesting the review be postponed – the first contact Israel had made with the council since March. Remigiusz Henczel, the council president, asked the ambassador to submit a formal request, which he failed to do.

With no formal request to delay the proceedings, the council was obliged to carry out the review in Israel’s absence on Tuesday.

The 47-member forum adopted a motion regretting Israel’s no-show and urging it to cooperate in a review to be conducted at its October-November session “at the latest”.

An alliance of 15 Palestinian and Israeli human rights organisations issued a joint statement on Tuesday [see below] warning of “far-reaching consequences” of Israel’s obstruction of the UN watchdog’s investigations, referring also to Israel’s refused to cooperate with a fact-finding mission into the Gaza conflict headed by Justice Richard Goldstone in 2009.

The group warned: “This lack of transparency will not only mean that Israel avoids rigorous criticism of its violations of international law, but that the entire UPR system will be undermined by the loss of its two fundamental principles: equality and universality.”

Washington also urged Israel to appear before the review if only to tell its side of the story, warning that boycotting the proceedings altogether would set a dangerous precedent.

NGO STATEMENT: Israel’s Obstruction of UN Human Rights Mechanisms Has Far-reaching Consequences

January 29, 2013

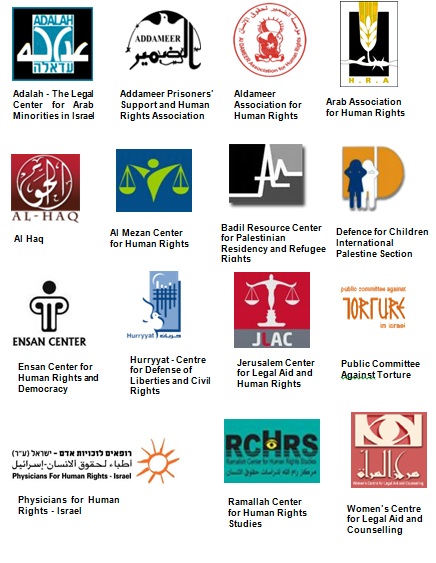

By:

Fifteen Israeli and Palestinian human rights organisations today warned of the far-reaching consequences of Israel’s refusal to fully co-operate with the United Nations (UN). On the morning of Israel’s second Universal Periodic Review (UPR), scheduled for Tuesday 29 January, it remains unclear whether it intends to participate.

This lack of transparency will not only mean that Israel avoids rigorous criticism of its violations of international law, but that the entire UPR system will be undermined by the loss of its two fundamental principles: equality and universality.

In May 2012, Israel formally announced its decision to “suspend its contact with the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the Human Rights Council (the Council) and its subsequent mechanisms”.

Israel reportedly met with the Council President His Excellency Remigiusz A. Henczel in January 2013 and discussed a postponement of its UPR. However, as no formal request has yet been made, the Council agreed to proceed as scheduled and to consider on the day what steps to take if the Israeli delegation does not attend.

These exceptional circumstances have created uncertainty and forced some civil society organisations to revise or limit their engagement with the review process due to the risk of investing necessarily significant resources into a process that may not take place. Thus, a key component of the UPR process – civil society engagement – has been severely hampered.

Through this uncertainty, Israel and the Council are setting a dangerous precedent on the international stage, one that could be followed by other States refusing to engage with the UN in order to avoid critical appraisals. Israel’s decision to disengage from core mechanisms of the United Nations human rights system has, in effect, resulted in preferential treatment. All but one of the 193 UN Member States have attended their UPR as scheduled; in that single instance the State of Haiti was unable to attend due to the humanitarian crisis caused by the 2010 earthquake. Israel should not receive any benefits or concessions for its efforts to undermine the system of the UN and, in particular, its human rights system.

To the contrary, the Council should ensure the unobstructed process of Israel’s UPR in accordance with the principles and standards set in the UPR mechanism, thereby reasserting the condition that human rights are more important than political or diplomatic considerations.

Moreover, Israel’s move to suspend cooperation with the Council and the OHCHR must be viewed within the context of its ongoing refusal to respect the decisions, resolutions and mechanisms of the UN. Consecutive Israeli governments have refused to recognise the State’s obligations under international human rights law with regard to the Palestinian population of the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt), obligations repeatedly reaffirmed in statements by UN treaty bodies.

Israel also rejects the de jure applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention, incumbent upon it as the Occupying Power, in defiance of numerous UN resolutions, the 2004 International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the oPt, and countless statements issued by governments worldwide.

In 2009, Israel declined to cooperate with the UN Fact-finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict, headed by Justice Richard Goldstone. Justice Goldstone repeatedly called on Israel to engage, to no avail. More recently, in 2012, the UN Fact-finding Mission on Israeli Settlements in the oPt was denied entry into the territory to collect testimonies. The Mission joined a long list of UN Special Rapporteurs and the Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights, to whom Israel has also refused entry. Furthermore, since his appointment as Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights on Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Mr. Richard Falk has not been allowed to enter the oPt to carry out his work.

Within this context, 15 human rights organisations call on the Council to take a firm stand consistent with the seriousness of Israel’s obstructive actions to date.

Adalah’s Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review of Israel

By Adalah

January 2013

The Palestinian Arab minority in Israel comprises close to 20% of the total population of the state, and numbers around 1,200,000 people. A part of the Palestinian people, they are citizens of Israel and belong to three religious communities: Muslim (81%), Christian (10%) and Druze (9%). Under international human rights instruments, they constitute a national, ethnic, linguistic and religious minority.

I. ISRAEL’S COMMITMENTS TO THE UPR, 2008

At its first Universal Periodic Review in 2008, Israel committed to:

Further address the remaining gaps between the various populations in Israeli society;

Strengthen efforts to ensure equality in the application of the law, to counter discrimination against persons belonging to all minorities, to promote their active participation in public life, such as through additional government resolutions to raise the percentage of the Arab minority in the civil service.

Israel has, however, failed to address either of these commitments adequately, and has, in fact, further increased inequality between the Palestinian Arab minority and Jewish majority in Israel through new discriminatory legislation and policies, as demonstrated in this report.

II. NORMATIVE AND INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

Constitutional and legislative framework

Israel lacks a written constitution or a basic law that constitutionally guarantees the right to equality before the law and prohibits direct or indirect racial discrimination. The Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty, considered a mini-bill of rights, does not enumerate a right to equality; on the contrary, it emphasizes the character of the state as a Jewish state.

The lack of a constitutionally-guaranteed right to equality has allowed Israel to enact over 40 discriminatory laws that relate only to the rights of Jewish citizens or abridge the rights of Arab citizens, or else use neutral language and general terminology, but have a discriminatory effect on Arab citizens of Israel. Indeed, since Israel’s first submission to the UPR in 2008, the Knesset has enacted 20 new discriminatory laws.

From 2009 to 2012, when one of the most right-wing government coalitions in the history of Israel was in power, Members of the Knesset (MKs) introduced a flood of discriminatory and often racist legislation that directly or indirectly targets Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel, in direct breach of Israel’s commitment to counter discrimination against persons belonging to minorities. Examples of these newest laws include:

the “Admissions Committee Law,” which de facto bans Arab citizens from living in hundreds of small community towns built on state land throughout Israel; the “Nakba Law,” which authorizes the Finance Minister to cut state funding to an institution if it holds an activity to commemorate the Nakba; the “Anti-Boycott Law”, which makes it a “civil wrong” to publicly call for a boycott of Israeli settlements in the West Bank’ and the “Economic Efficiency Law”, which affords ministers sweeping discretion to award a range of unspecified lucrative benefits to towns and villages (namely Jewish communities) within designated “National Priority Areas”.

III. PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Right to participate in political life

In recent Knesset elections (2003, 2006 and 2009), right-wing political parties, MKs and activists, and even a former Attorney General, have attempted to disqualify Arab parties and individual MKs from running for seats in the legislature. These ongoing attempts seek to limit the political voice of Arab citizens and entrench their political marginalization and breach Israel’s commitment to promote the active participation of minorities in public life.

In the last Knesset elections, in 2009, the Central Elections Committee (CEC) voted to ban two Arab parties from running, namely the National Democratic Assembly (NDA)-Balad and the United Arab List and Arab Movement for Change (UALAMC). The disqualification motions centered on the parties’ political platforms and statements by their leaders demanding, e.g., the establishment of a “state for all its citizens” or allegations of supporting terrorism by traveling to or assisting travel to “enemy states”, under Section 7A of The Basic Law: The Knesset. In response to the CEC’s decision, which was supported by the Likud, Labor and Kadima political parties, Adalah filed a Supreme Court appeal arguing that banning the parties from standing for election would deny the Arab minority an effective vote and harm their rights to elect their own representatives and run for elected political office. In January 2009, an expanded nine-justice panel of the Supreme Court overturned the CEC‘s decisions to ban the parties. Before the upcoming elections on 22 January 2013, further disqualification motions are expected to be filed against Arab parties and MKs.

Moreover, Adalah is currently representing Arab MKs Haneen Zoabi, MK Dr. Ahmad Tibi, MK Sa’id Naffaa, and MK Mohammed Barakeh. These MKs, as well as all of the political leadership of the Palestinian Arab minority in Israel, face sustained and severe attack and harassment from Israeli government officials and incitement from extreme right-wing MKs. MK Zoabi has been stripped of some of her parliamentary privileges, and MK Barakeh and MK Naffaa were stripped of their immunity, and are facing criminal indictments for their legitimate and protected political activity. In another case, the Knesset refused to permit the introduction of legislation submitted by MK Tibi seeking to prohibit Nakba denial. These attacks violate Arab citizens’ rights to genuine political participation; the MKs freedom of opinion and expression, free association and peaceful assembly; and the right to equal protection of the law and nondiscrimination before the law.

Participation of minorities in public service

Despite making up 20% of Israel’s population, Palestinian citizens are greatly underrepresented in the public service. According to the Civil Service Commission, the number of Arab employees in the civil service was 4,982 in 2011, or 7.8% of the total. This is only a small increase from 4,245 (7.0%) in 2009. The percentage of Arab women in the civil service is even lower. In 2011, only 2.9% of Arab employees in the service were women, marginally up from 2.8% in 2010, 2.6% in 2009, and 2.4% in 2008.

Arabs are also underrepresented in all government ministries that have a decisive impact on their lives, such as the Ministries of Health (7.2%), Education (6.2%), Transport (2.3%), Housing (1.3%) and Finance (1.2%),and rarely found in decision-making posts. A number of government decisions have been issued over the past decade that order the implementation of interim quotas for the representation of Arab men and women, including the target of 10% by 2010, and again in 2012. The government consistently fails to reach these targets.

Right to work and favorable conditions of employment

Due to the state’s unequal allocation of resources in favor of the Jewish population, Arab citizens of Israel generally have limited employment opportunities and therefore a relatively low socio-economic status. The state has long implemented a policy of locating employment generating industrial zones in or near to Jewish towns and villages, almost entirely excluding Arab towns and villages. For example, the state budget for 2008 allocated a total sum of NIS 215 million for developing industrial zones, of which just NIS 10 million was earmarked for Arab towns and villages.

Only 2.4% of all industrial zones in Israel are located in Arab towns and villages. Similarly, governmental incentives for new businesses and entrepreneurs are sorely lacking in Arab towns and villages. Aggravating the problem is the absence of frequent public transportation from many Arab towns and villages to central cities, which makes it more difficult for Arab citizens, particularly for women and young people who often do not own cars, to work elsewhere. In addition, Arab citizens often have to travel long distances to reach employment offices, few of which are located in Arab towns and villages.

The state’s discriminatory economic policies serve to entrench the disadvantaged status of Arab citizens. In 2011, for example, the employment rate for Arab men (aged 25-64) was 72.2%, compared to 81.4% for Jewish men. More starkly, the employment rate among Arab women in the same age cohort was only 26.8%, compared with 75.3% for Jewish women. The average gross monthly income among Arab male workers was 42% lower than for Jewish male workers in 2008, and the average gross monthly income for Arab female workers was 28% lower than for Jewish female workers in the same year.

It is therefore unsurprising that in 2008, 53.5% of all Arab families in Israel were classified as poor, compared to an average of 20.5% among all families in Israel. The figure is far higher among Arab Bedouin families in Israel, at 67.2% in 2007. While Arab citizens constitute around 20% of the total population of Israel they accounted for 44.5% of the poor population in 2008. The net monthly income of Arab households was just 63% of the net monthly income of Jewish households in 2007, despite the larger average size of Arab families. According to Israel’s National Insurance Institute, there was an increase of 1.2% in the number of Arab families living below the poverty line between 2009 and 2010, compared to a parallel decrease of 8.3% in the number of Jewish families.

Thus, Israel has not upheld its commitment to reduce gaps between Arab and Jewish citizens.

Right to health and social security

The National Health Insurance Law (1995) requires the healthcare system to provide equitable, high-quality health services to all citizens of Israel. However, Palestinian citizens of Israel face numerous barriers that prevent them from exercising their right to the highest sustainable standard of health. Notably there is a lack of clinics and hospitals in Arab towns and villages:

Nazareth is the only Arab town in Israel with hospitals and these three hospitals are not state hospitals, but are church-run. All state hospitals are in Jewish or mixed cities. The limited provision of public transportation to and from Arab towns and villages exacerbates the problem. Specialized health facilities for disabled children are also lacking or woefully inadequate in Arab towns and villages. Further, Palestinian citizens of Israel may face a language barrier, since most health-service providers speak only Hebrew. The problem of access to healthcare and mobility is particularly acute in the Naqab in the south of Israel. Unrecognized Arab Bedouin villages, which are referred to by the state as “illegally constructed villages” and afforded no legal status, lack on-site health facilities and clinics, and in the absence of public transport hospitals located elsewhere are inaccessible to many villagers.

The effects of inadequate health care are reflected in the persisting gaps in the health indicators of Arab and Jewish citizens. For example, according to official data, in 2008 infant mortality rates among the Jewish majority in Israel stood at 2.9 per 1,000 live births, while for Palestinians the rate was 6.5 per 1,000 live births. For the Arab Bedouin, the rate is even higher, at 11.5 per 1,000 live births in 2008. The fact that Arab Bedouin children have the highest rates of disease and infections in the country, can be in large part attributed to the state’s refusal to provide accessible healthcare for them or their mothers, as well as its refusal to connect dozens of unrecognized villages to the water network. In 2008, the average life expectancy for Arab men was just 75.9 years, compared to 79.9 years for Jewish men; the life expectancy for Arab women was 79.7 years, compared to 83.3 years for Jewish women.

Right to educational standards

Arab children in Israel make up 25% of the country’s school students, at around 480,000 pupils. From elementary to high school, Arab and Jewish students learn in separate schools. While Arab schools have a separate curriculum taught in Arabic, it is designed and supervised by the Education Ministry, where Arab educators have little-to-no decision-making powers. Students in Arab state-run schools receive very little instruction in Palestinian or Arab history, literature and culture, and spend more time learning the Torah than the Qur’an or the New Testament. The Arab education system faces systematic, institutionalized discrimination that negatively affects the education outcomes of Arab children. Although Israel does not regularly release official data detailing how much it spends in total on each Arab and Jewish student (a major gap in transparency), the state’s under-funding of the Arab education system is visibly manifested in the poor infrastructure and facilities characteristic of Arab schools and the more crowded classrooms. Underinvestment in Arab education is most blatant in the Naqab, where Arab Bedouin schools often lack services and facilities, including toilets, electricity, telephone and internet, and safe access roads, particularly in the unrecognized villages that have schools.

As a result of the state’s negligence, Jewish school children in Israel outperform Arab children from early on in their education. In the 2009/10 academic year, 38.3% of Arab students received matriculation certificates, compared to 54.4% of Jewish students. Another alarming trend is the high dropout rates: 7.2% of Arab students dropped out of school compared to 3.7% of Jewish students in 2006-2008; between grades 9 to 11, the dropout rates were 8.7% among Arabs and 4.4% among Jews. These trends attest to the state’s inability or unwillingness to address the inequalities, entrenching the gaps between Arab and Jewish children.

Rights of minorities and indigenous peoples

Arab Bedouin citizens of Israel, inhabitants of the Naqab desert since at least the 7th century CE, are the most vulnerable community. For over 60 years, Israel has pursued policies of mass displacement, home demolitions and dispossession of the Arab Bedouin from their ancestral land. Today, 70,000 Arab Bedouin live in 35 “unrecognized” villages that either predate the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, when around 85% of the Bedouin were expelled or displaced, or were created by Israeli military order in the early 1950s. Israel considers the villages “unrecognized” and their inhabitants “trespassers on State land”, and denies citizens who live in them access to basic infrastructure like water, electricity, sewage, education, health care and roads. If Israel applied the same criteria for planning and development that are applied in the Jewish rural sector, all 35 unrecognized villages would be recognized.

In September 2011, the government approved the Plan for the Regulation of the Settlement of the Bedouin in the Negev, or the “Prawer Plan”. The plan will lead to the forced displacement of tens of thousands of Arab Bedouin citizens of Israel from their homes and land in the unrecognized villages in the Naqab. The Bedouin citizens affected by this plan will be concentrated in over-crowded and under-funded government-planned townships, which are unsuited to their traditional way of life, and offered meager compensation. Despite complete rejection of the plan by the Arab Bedouin, and strong condemnation from the international community, the Prawer Plan is being implemented now. More than 1,000 houses were demolished in 2011 alone, and civil society is seeing the same practices in 2012. Since the Prawer Plan was announced, the government has informed of plans that will displace over 10,000 people and plant forests, build military centers, and establish new Jewish towns and villages in their place.

Suggested Questions for the UN Universal Periodic Review of Israel, January 2013

By Adalah – The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel

November 30, 2012

Constitutional and legislative framework

Please indicate whether the State party envisages including the right to equality and the prohibition of discrimination explicitly in the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty. In the absence of a constitutionally-guaranteed right to equality – or even an ordinary statute that guarantees equality for all citizens – how does the State of Israel reconcile its duties under international human rights law to ensure equal rights and protections to all its citizens and to protect them against discrimination?

Many Israeli laws include the terms “Jewish and democratic State”, “the values of the State as a Jewish State”, and/or refer to “Israel’s heritage” as a source of law. Why does this not constitute discrimination against non-Jews, in particular, the Arab minority?

Right to participate in political life

The frequency of disqualification motions in advance of the Israeli general elections targeted explicitly against Arab political leaders and Arab political parties is deeply concerning in regards to the protection of the democratic and political rights of the Arab minority in Israel. Furthermore, the fact that the promotion of a “state for all its citizens” is being inferred as grounds for disqualification from the Israeli elections is very concerning, as it contradicts democratic principles.

What measures will the state take to ensure the right of Arab citizens of Israel to political participation, including for all Arab political parties and Arab political leaders in the upcoming national elections in January 2013? Further, what steps will the State Party take against the severe attacks and harassment of Arab members of Knesset?

Participation of minorities in public service

Seeing that the rate of Arab employment in the civil service has failed to reach the interim quotas set out by the government, what new measures or strategies will Israel take to increase the representation of Arab citizens in public services, particularly Arab women? How will the state ensure that Arab citizens are adequately represented in all government ministries that have a direct impact on their lives, including the Ministries of Health, Education, Transport, Housing and Finance? What measures will the state take to facilitate the promotion of Arab employees to higher positions in government ministries?

Right to work and favorable conditions of employment

What policies will Israel implement to alleviate the high rate of poverty among Arab citizens? How does Israel plan to address the unequal allocation of state resources that disadvantages Arab localities, including the lack of employment-generating industrial zones in Arab towns and villages? What measures is Israel taking to increase the employment rate of Arab citizens, particularly Arab women? What measures will Israel take to bridge the gap between income earned by Jewish and Arab citizens of the state?

The lack of public transportation in Arab towns and villages is also a major obstacle that hinders Arab citizens’ ability to go to their places of work, which are often in other cities and are long distances away from their homes. What steps will be taken to improve the availability of public transportation services for workers in Arab towns and villages?

Right to health and social security

Given the lack of health clinics or hospitals in Arab towns and villages as compared to Jewish towns, and the barriers faced by Arab citizens in receiving health access such as language and transportation, how will the state ensure that Arab citizens are provided adequate health care services and equal health rights? What measures is Israel taking to address the pervasive discrepancies in health indicators between the Jewish, Arab and Arab Bedouin populations, including the infant mortality rates and life expectancy rates, particularly in light of comments that the state is not providing adequate resources to thousands of Arab Bedouin citizens in unrecognized villages in the Naqab (Negev) region?

Right to equal educational standards

How does Israel plan to reduce the gap in educational resources allocated between Jewish and Arab students, particularly in light of the absence of many basic services and facilities for Arab Bedouin students in the Naqab? What measures is Israel taking to reduce the high dropout rates of Arab students? Why do Arab schools receive very little instruction in Palestinian and Arab history, geography, literature and culture? How will the state facilitate greater representation of Arab citizens in higher positions in the Ministry of Education?

Rights of minorities and indigenous peoples

“The Plan for the Regulation of Settlement of the Bedouin in the Negev” (also known as the Prawer Plan) is a source of great concern, as, if fully implemented it will displace and dispossess tens of thousands of Arab Bedouin from their homes and villages in the Naqab.

Why does the state refuse to officially recognize the so-called “unrecognized” Arab Bedouin villages? In particular, why does the state withhold recognition of these villages while neighboring Jewish towns have been allowed to grow and expand? What steps is Israel taking to respect and protect the rights of Arab Bedouin children living in the unrecognized villages in the Naqab to an adequate standard of living and to provide them with basic infrastructure and services? Why doesn’t the state consider alternatives to home demolitions, evacuations and other forms of forced relocation for the Arab Bedouin? Are there any processes in place for Arab Bedouin citizens of Israel in these villages to continue living on their traditional ancestral lands in the Naqab?

What is the Universal Periodic Review?

The Universal Periodic Review “has great potential to promote and protect human rights in the darkest corners of the world.” – Ban Ki-moon, UN Secretary-General

UN Office of the High COmmissioner for Human Rights

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a unique process which involves a review of the human rights records of all UN Member States. The UPR is a State-driven process, under the auspices of the Human Rights Council, which provides the opportunity for each State to declare what actions they have taken to improve the human rights situations in their countries and to fulfil their human rights obligations. As one of the main features of the Council, the UPR is designed to ensure equal treatment for every country when their human rights situations are assessed.

The UPR was created through the UN General Assembly on 15 March 2006 by resolution 60/251, which established the Human Rights Council itself. It is a co-operative process which, by October 2011, has reviewed the human rights records of all 193 UN Member States. Currently, no other universal mechanism of this kind exists. The UPR is one of the key elements of the Council which reminds States of their responsibility to fully respect and implement all human rights and fundamental freedoms. The ultimate aim of this mechanism is to improve the human rights situation in all countries and address human rights violations wherever they occur.