Israel locked into its stifling fears

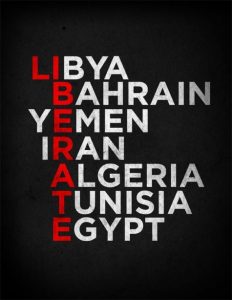

An Israeli spring?

Rejecting the prospect of greater democracy in the Arab world could put the Jewish state at risk

Avi Shlaim, Spectator

25.02.12

The revolutions sweeping through the Arab lands present Israel with a historic opportunity: to become part of the region in which it is located and to join with pro-democracy forces in forging a new Middle East. So far, however, the Arab Spring has not resonated well at any level of Israeli society. Israel’s leaders have ignored the opportunities and greatly inflated the risks and dangers arising out of the Arab Spring. Consequently, the dreams of the young pro-democracy protesters have turned into the stuff of nightmares for Israeli strategic planners. A reappraisal is urgently needed to stop the Arab Spring from becoming Israel’s winter.

Israel has always prided itself on being an island of democracy in a sea of authoritarianism. It has received a huge amount of international sympathy and support since its birth in 1948 precisely because it has been one of the very few democracies in the region. Yet Israel has done nothing to promote democracy in the Arab world and, as the cache of 1,600 diplomatic documents leaked last year reveals, a great deal to undermine Palestinian democracy. The truth of the matter is that most Israelis look on their Arab neighbours with disdain and distrust and have no wish to become part of the region.

True, an Israeli social protest movement emerged last summer and it was influenced by the example of the Arab awakening. The agenda of the demonstrators in Tel Aviv’s leafy Rothschild Boulevard is strikingly similar to that of their Arab counterparts. On both sides of the Arab-Israeli divide, the demonstrators demand jobs, housing, economic opportunity and social justice. And on both sides the protests sprung from the same source: the failure of the neo-liberal model of development. Yet the Israeli demonstrators deny affinity or solidarity with the social protest movements beyond their borders. They do so for fear of being denounced as unpatriotic in an increasingly ethnocentric and chauvinistic society.

A comparison of the agendas of the Arab and Israeli protest movements does reveal, however, one missing link: the situation in the occupied Palestinian territories. In the early days of the Arab Spring, the focus of attention seemed to shift from the long-standing preoccupation with the Palestinian-¬Israeli conflict to the internal problems of Arab society. The young liberals in the vanguard of the uprisings did not dwell on this perennial issue. Yet before long, justice for the Palestinians re-emerged as one of the major issues in the debates, the posters and the slogans of the mass movement they were leading. This presented Israel with an ¬opportunity: instead of dealing only with Arab dictators, to start dealing with the Arab street.

The young Israeli liberals and leftists in the vanguard of the 14 July movement were given a rare chance to reach out to the whole region on a matter of common concern. They know only too well that the staggering subsidies that support the settlers in the occupied territories mean there is less money for housing, education and welfare in Israel. Many of the activists who helped to launch the social protest movement in Tel Aviv are also active in the peace camp that calls for an end to the occupation and for a two-state solution. But they made a tactical decision to focus on one set of issues in order to maximise their impact at home.

Beyond the protest movement, there is a widespread suspicion in Israel that the real leaders of the Arab uprisings are not the young idealists who appear before the television cameras but Islamic extremists dedicated to the annihilation of the Jewish state. Despite much evidence to the contrary, Israelis cling to the reductionist notion that political Islam is incompatible with democracy and that Arabs are not fit for democracy anyway. What the uprisings actually suggest is that ordinary Arabs, like ordinary people anywhere else in the world, want freedom, liberty, social justice, human rights and human dignity. Israeli pundits, however, persist in purveying all the same old stereotypes of sinister Islamists waiting in the wings and plotting democracy of the ‘one man, one vote, one time’ variety. The result of the Arab awakening, the pundits predict, will not be democracy but an Islamic theocracy more intolerant and more vicious than the secular autocracies it is struggling to replace.

Prime Minister Benjamin ¬Netanyahu is a prime example of his country’s double standards when it comes to democracy on the other side of the hill. In the past he always maintained that peace and security depended on an Arab shift towards democracy. Echoing the ‘democratic peace theory’ propounded by western political scientists, he liked to point out to foreign journalists that ‘democracies don’t fight each other’. He used to argue against relinquishing territory to undemocratic regimes on the grounds that they are unreliable and untrustworthy. The dawn of a democratic era in the Arab world made him change his tune. Now he argues that because of the turmoil in the region, Israel would have to maintain permanent military control over the Jordan Valley even in the context of a peace settlement with the Palestinians. Thus, paradoxically, the democratic shift in the Arab lands has led Netanyahu to harden his already unacceptable terms for a settlement with the Palestinians.

•••

Netanyahu grudgingly accepted in June 2009 the idea of an independent Palestinian state but all the policies of his government are deliberately directed at frustrating the emergence of one. This is obvious from the refusal to freeze settlement activity on the West Bank to give peace talks a chance. Land-grabbing and peacemaking do not go together: it is one or the other, and Netanyahu’s right-wing government has opted for territorial expansion at the expense of the Palestinians. By pressing ahead with the Zionist colonial project on the West Bank and in East Jerusalem, Netanyahu seeks to foreclose forever any chance of genuine independence and statehood for the Palestinians. The tragedy is that, by consolidating the occupation, Netanyahu also deprives his own people of hope of a better future. As Karl Marx observed, a people that oppresses another cannot itself remain free.

Netanyahu is not a man of peace; he is a proponent of the doctrine of permanent conflict. One of his better-known soundbites is: ‘We live in a tough neighbourhood.’ This characterisation of the region is undoubtedly true but it ignores Israel’s part in making the Middle East such a tough neighbourhood by its disregard for the rights of others, by shunning diplomacy, by its reliance on brute military force, by its daily abuses of Palestinian human rights, and by its flagrant violations of international law.

Netanyahu himself epitomises the arrogance of power. For him the Arab Spring evokes only dangers and his only response is to increase Israel’s military power. In a speech to the Knesset last year, Netanyahu blasted western politicians who support the Arab Spring and accused the Arab world of ‘moving not forward, but backward’. He himself had forecast that the Arab Spring would turn into an ‘Islamic, anti-western, anti-liberal, anti-Israeli and anti-democratic wave’. Time had proved him right, he claimed.

Netanyahu’s public statements reflect the views of Israel’s powerful defence establishment. Retired Major General Amos Gilad stated his position with blinding frankness in the annual policy gathering in Herzliya. ‘In the Arab world, there is no room for democracy,’ he told a nodding audience. ‘This is the truth. We prefer stability.’ Other security experts have started talking about an Islamic encirclement of their country, of a ‘poisonous crescent’ consisting of Iran, Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza, and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. But the more immediate danger is that Israel’s leaders will succumb to imperial paranoia.

The alternative is to seize the historic opportunity offered by the Arab Spring to make peace with the Palestinians and the rest of the Arab world. The best blueprint for peace with the Palestinians is President Clinton’s ‘parameters’ of December 2000: an independent Palestinian state over the whole of Gaza and 94-96 per cent of the West Bank with a capital in East Jerusalem. There is also the Saudi peace plan which was endorsed by all 22 members of the Arab League at their Beirut summit in March 2002. This plan offers Israel peace and normalisation with all 22 members in return for withdrawal from all occupied Arab land and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza. Israel’s leaders, as is their wont, chose to ignore this remarkable offer.

Today, in the wake of the Arab awakening, Israel has a unique opportunity to replace the doctrine of permanent conflict with a commitment to comprehensive peace with its Arab neighbours. The choice is between continuing to behave like the blustering neighbourhood bully and helping with the democratic transformation of the Middle East. Israel’s leaders, like politicians everywhere, are free of course to repeat the mistakes of the past but it is not mandatory to do so. If they choose the bully over the democratic role model, their country may well end up on the wrong side of history.

Avi Shlaim is an emeritus professor of international relations at Oxford University and the author of Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations. He was born in Baghdad and grew up in Israel, where he served in the Israel Defence Forces from 1964 to 1966.